Developing countries are supposed to grow more rapidly than rich countries. For example, China has maintained a growth rate of close to 10 percent annually for three decade. India has recently approached this range. Argentina’s growth averaged almost 7 percent over the last decade.

By contrast, Mexico’s per capita GDP growth has actually trailed that of the United States. This naturally leads the Post to run a front page piece today telling readers that “Mexico’s middle class is becoming its majority,” a fact which it attributes in part to NAFTA.

Yes, this always happens in slow growing countries. Those who care about data will note that per capita income in Mexico fell from 32.4 percent of per capital income in the United States in 1993, the last pre-NAFTA year, to 31.4 percent in 2011. But hey, why let the data get in the way of a good story? At least the Post didn’t try to claim that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled from 1987 to 2007, again.

This NYT front page story on the surge of kidnapping in Mexico provides an interesting contrast.

Developing countries are supposed to grow more rapidly than rich countries. For example, China has maintained a growth rate of close to 10 percent annually for three decade. India has recently approached this range. Argentina’s growth averaged almost 7 percent over the last decade.

By contrast, Mexico’s per capita GDP growth has actually trailed that of the United States. This naturally leads the Post to run a front page piece today telling readers that “Mexico’s middle class is becoming its majority,” a fact which it attributes in part to NAFTA.

Yes, this always happens in slow growing countries. Those who care about data will note that per capita income in Mexico fell from 32.4 percent of per capital income in the United States in 1993, the last pre-NAFTA year, to 31.4 percent in 2011. But hey, why let the data get in the way of a good story? At least the Post didn’t try to claim that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled from 1987 to 2007, again.

This NYT front page story on the surge of kidnapping in Mexico provides an interesting contrast.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Politicians don’t always say what they are thinking. Most of us know this fact. Unfortunately, the folks at the Washington Post don’t. In a major front page article on the budget negotiations last summer between President Obama and the Republican leadership the Post told readers:

“Another key caveat: Much of the $800 billion would have to come from overhauling the tax code — not from higher tax rates. The Republicans believed lower rates and a simpler code would generate new revenue by discouraging cheating and spurring economic growth.”

The Post actually has no clue what Republicans “believed.” It only knows what Republicans say.

Suppose for a moment that Republicans want to lower tax rates for the wealthy because they get large campaign contributions from wealthy people who want to see their tax rates go down. It is unlikely that Republicans would go around telling the public that they want to lower tax rates for the wealthy because wealthy people feel like paying less money in taxes.

They would need some alternative argument that might have appeal beyond the 1-2 percent of the public that benefits from lower tax rates. The claim that lower tax rates on the wealthy will lead to more growth, thereby benefiting everyone, is one such argument.

While it is possible that Republicans actually believe this claim, it is also possible that they are just saying it for political purposes and know it to be false or simply care whether or not it is true. It irresponsible for a newspaper to tell us that politicians’ statements actually reflect their view of the world when it has no basis whatsoever for this assertion.

Politicians don’t always say what they are thinking. Most of us know this fact. Unfortunately, the folks at the Washington Post don’t. In a major front page article on the budget negotiations last summer between President Obama and the Republican leadership the Post told readers:

“Another key caveat: Much of the $800 billion would have to come from overhauling the tax code — not from higher tax rates. The Republicans believed lower rates and a simpler code would generate new revenue by discouraging cheating and spurring economic growth.”

The Post actually has no clue what Republicans “believed.” It only knows what Republicans say.

Suppose for a moment that Republicans want to lower tax rates for the wealthy because they get large campaign contributions from wealthy people who want to see their tax rates go down. It is unlikely that Republicans would go around telling the public that they want to lower tax rates for the wealthy because wealthy people feel like paying less money in taxes.

They would need some alternative argument that might have appeal beyond the 1-2 percent of the public that benefits from lower tax rates. The claim that lower tax rates on the wealthy will lead to more growth, thereby benefiting everyone, is one such argument.

While it is possible that Republicans actually believe this claim, it is also possible that they are just saying it for political purposes and know it to be false or simply care whether or not it is true. It irresponsible for a newspaper to tell us that politicians’ statements actually reflect their view of the world when it has no basis whatsoever for this assertion.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

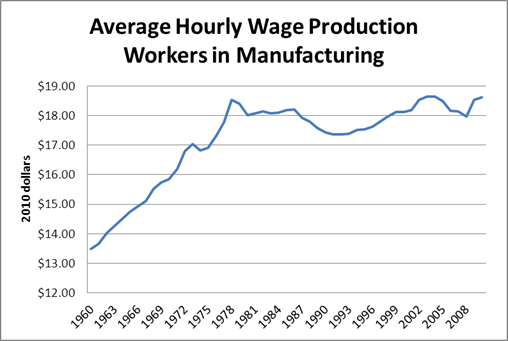

Charles Murray is back in the Wall Street Journal rejecting the idea that poor economic prospects had anything to do with the fact that so many whites without college degrees dropped out of the labor force. There are a few points that are worth noting about this story.

First Murray does a bizarre comparison by looking at real wages between 1960 and 2010. This is bizarre because wages rose rapidly through the sixties and into the early seventies, then largely stagnated. (I am using manufacturing workers to pick a typical job held by non-college educated white makes.)

Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Note that there is some increase in real wages in the late 90s, the first period of sustained low unemployment since the late 60s. Interestingly, these wage gains coincided with the first period of sustained low unemployment since early 70s. Also, if we look at the graph that Murray has with his article we see that the labor force participation for whites with just a high school degree actually rose slightly in this period, reversing the long-term trend. That might suggest that labor market conditions are a big part of this story.

There are two other points worth considering in this story. First, the share of white males with just a high school degree (i.e. no college or even vocational training) has fallen sharply over this period. In other words, whites with just a high school degree are a smaller and relatively less educated segment of the white work force today than was the case 40 years ago.

The other point is that we might think that relative income means something. In a thirty year period where per capita income more than doubled, we might expect that workers would have at least something to show. The fact that the wages of white males with just high school degrees has barely budged in three decades indicates that their situation has deteriorated seriously in relative terms.

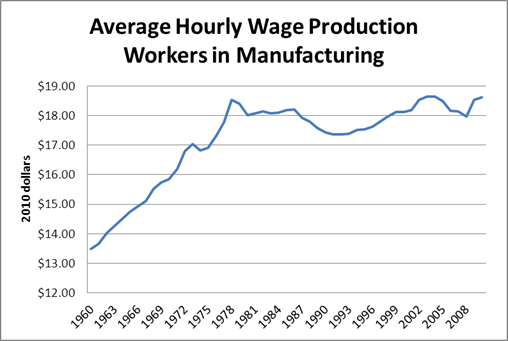

Charles Murray is back in the Wall Street Journal rejecting the idea that poor economic prospects had anything to do with the fact that so many whites without college degrees dropped out of the labor force. There are a few points that are worth noting about this story.

First Murray does a bizarre comparison by looking at real wages between 1960 and 2010. This is bizarre because wages rose rapidly through the sixties and into the early seventies, then largely stagnated. (I am using manufacturing workers to pick a typical job held by non-college educated white makes.)

Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Note that there is some increase in real wages in the late 90s, the first period of sustained low unemployment since the late 60s. Interestingly, these wage gains coincided with the first period of sustained low unemployment since early 70s. Also, if we look at the graph that Murray has with his article we see that the labor force participation for whites with just a high school degree actually rose slightly in this period, reversing the long-term trend. That might suggest that labor market conditions are a big part of this story.

There are two other points worth considering in this story. First, the share of white males with just a high school degree (i.e. no college or even vocational training) has fallen sharply over this period. In other words, whites with just a high school degree are a smaller and relatively less educated segment of the white work force today than was the case 40 years ago.

The other point is that we might think that relative income means something. In a thirty year period where per capita income more than doubled, we might expect that workers would have at least something to show. The fact that the wages of white males with just high school degrees has barely budged in three decades indicates that their situation has deteriorated seriously in relative terms.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

NPR deserves some serious congratulations. As a matter of policy they now reject the concept of he said/she said journalism; creating the image of balance even when one said is clearly true and the other isn’t.

This would mean, for example, they would not just air Republican complaints that the Obama administration is responsible for the high price of gas and the Obama administration’s response that the price of oil is determined in world markets, which can only be affected to a very limited extent by U.S. production. It will now tell listeners that the price of oil is in fact determined in world markets and that U.S. production is a relatively small fraction of world production.

This is a huge step forward for NPR, and because of its standing, news reporting more generally. They definitely deserve to be commended for this stance. Let’s hope they live up to it.

NPR deserves some serious congratulations. As a matter of policy they now reject the concept of he said/she said journalism; creating the image of balance even when one said is clearly true and the other isn’t.

This would mean, for example, they would not just air Republican complaints that the Obama administration is responsible for the high price of gas and the Obama administration’s response that the price of oil is determined in world markets, which can only be affected to a very limited extent by U.S. production. It will now tell listeners that the price of oil is in fact determined in world markets and that U.S. production is a relatively small fraction of world production.

This is a huge step forward for NPR, and because of its standing, news reporting more generally. They definitely deserve to be commended for this stance. Let’s hope they live up to it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds won’t hit 3.0 percent until the third quarter of 2014 and that even at the end of the next presidential term they will still be hovering near 4.0 percent, a lower rate than at any point during the budget surplus years of the Clinton administration.

This might lead people to think that budget deficits are not having a serious negative effect in driving up interest rates. But David Brooks tells readers that CBO is wrong:

“In December, a re-elected Obama would face three immediate challenges: the expire; there will be another debt-ceiling fight; mandatory spending cuts kick in. In addition, there will be an immediate need to cut federal deficits. During the , the government could borrow gigantic amounts without pushing up interest rates because there was so little private borrowing. But as the economy recovers and demand for private borrowing increases, then huge public deficits on top of that will push up interest rates, crowd out private investment and smother the recovery.”

Wow, it would be great if Brooks could share the analysis he used to determine that interest rates are about to spike and derail the recovery. I do my best to keep on top of new economic research, but I have no clue what Brooks could be talking about. Maybe he could share it with readers in a future column.

Brooks apparently also did not know that President Obama put out a budget for fiscal year 2012. His column said that:

“One of the crucial moments of his presidency came in April of last year. Usually, presidents lead by proposing a budget and everybody reacts. But Obama decided to hang back and let Representative Paul Ryan propose a Republican budget. Then, after everybody saw the size of the cuts Ryan was proposing, Obama could come in with his less scary alternative. That is cageyness personified.”

Actually, President Obama did put out a budget in February of 2011, two months before Representative Ryan put out his plan.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds won’t hit 3.0 percent until the third quarter of 2014 and that even at the end of the next presidential term they will still be hovering near 4.0 percent, a lower rate than at any point during the budget surplus years of the Clinton administration.

This might lead people to think that budget deficits are not having a serious negative effect in driving up interest rates. But David Brooks tells readers that CBO is wrong:

“In December, a re-elected Obama would face three immediate challenges: the expire; there will be another debt-ceiling fight; mandatory spending cuts kick in. In addition, there will be an immediate need to cut federal deficits. During the , the government could borrow gigantic amounts without pushing up interest rates because there was so little private borrowing. But as the economy recovers and demand for private borrowing increases, then huge public deficits on top of that will push up interest rates, crowd out private investment and smother the recovery.”

Wow, it would be great if Brooks could share the analysis he used to determine that interest rates are about to spike and derail the recovery. I do my best to keep on top of new economic research, but I have no clue what Brooks could be talking about. Maybe he could share it with readers in a future column.

Brooks apparently also did not know that President Obama put out a budget for fiscal year 2012. His column said that:

“One of the crucial moments of his presidency came in April of last year. Usually, presidents lead by proposing a budget and everybody reacts. But Obama decided to hang back and let Representative Paul Ryan propose a Republican budget. Then, after everybody saw the size of the cuts Ryan was proposing, Obama could come in with his less scary alternative. That is cageyness personified.”

Actually, President Obama did put out a budget in February of 2011, two months before Representative Ryan put out his plan.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT reported that India is seeing somewhat of a growth slowdown, telling readers that growth slowed from 9.9 percent in 2010, to 7.4 percent last year, and a projected 7.0 percent this year. It then added:

“while that is fast relative to developed countries, most economists consider it laggardly.”

Actually, 7.0 percent growth is fast relative to the growth rate in the vast majority of developing countries as well. For example, last year Argentina and Panama were the only countries in Latin America to achieve a growth rate in excess of 7.0 percent. While India can likely grow more rapidly than this, 7.0 percent is still an impressive growth rate by most standards.

The NYT reported that India is seeing somewhat of a growth slowdown, telling readers that growth slowed from 9.9 percent in 2010, to 7.4 percent last year, and a projected 7.0 percent this year. It then added:

“while that is fast relative to developed countries, most economists consider it laggardly.”

Actually, 7.0 percent growth is fast relative to the growth rate in the vast majority of developing countries as well. For example, last year Argentina and Panama were the only countries in Latin America to achieve a growth rate in excess of 7.0 percent. While India can likely grow more rapidly than this, 7.0 percent is still an impressive growth rate by most standards.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Charles Krauthammer is angry at President Obama for not allowing more oil drilling and delaying the Keystone Pipeline. He suspects that he doesn’t like fossil fuels. (There’s something called “global warming,” which could lead to hundreds of millions of deaths due to floods and droughts, but hey, we don’t talk about that here.)

Anyhow, Krauthammer is upset that President Obama keeps saying that drilling everywhere all the time will not bring down the price of oil. Of course this happens to be true.

Even if we told BP and the other oil companies we don’t care how many people they kill in the process (11 workers died in the Deepwater Horizon explosion) and whose land and beaches they destroy (in other words, no respect for private property) they could at most increase production by 1-2 million barrels a day, and even this increase would take years to bring about.

That would increase would supplies by around 2 percent, perhaps leading to a reduction in price on the order of 5 percent. If Krauthammer has research that shows something different, he should share it with readers.

The Keystone pipeline would mostly have the effect of redistributing gas within the U.S. It would lead to higher prices in the Midwest and somewhat lower prices on the East Coast.

Krauthammer also criticizes Obama for claiming that reduced demand will lower prices. While Obama is wrong if he literally meant that reduced demand would mean lower gas prices, if he meant that increased efficiency would lower energy costs, then he is absolutely right. It costs half as much to drive a car a mile if it gets 40 miles a gallon than if it gets 20 miles a gallon.

One last point, Krauthammer is upset that President Obama is spending 0.0004 percent of the federal budget on research into using algae as a fuel source. If we cut this spending, that apparently Krauthammer knows to be foolish, we could rebate 5 cents to every person in the country.

Charles Krauthammer is angry at President Obama for not allowing more oil drilling and delaying the Keystone Pipeline. He suspects that he doesn’t like fossil fuels. (There’s something called “global warming,” which could lead to hundreds of millions of deaths due to floods and droughts, but hey, we don’t talk about that here.)

Anyhow, Krauthammer is upset that President Obama keeps saying that drilling everywhere all the time will not bring down the price of oil. Of course this happens to be true.

Even if we told BP and the other oil companies we don’t care how many people they kill in the process (11 workers died in the Deepwater Horizon explosion) and whose land and beaches they destroy (in other words, no respect for private property) they could at most increase production by 1-2 million barrels a day, and even this increase would take years to bring about.

That would increase would supplies by around 2 percent, perhaps leading to a reduction in price on the order of 5 percent. If Krauthammer has research that shows something different, he should share it with readers.

The Keystone pipeline would mostly have the effect of redistributing gas within the U.S. It would lead to higher prices in the Midwest and somewhat lower prices on the East Coast.

Krauthammer also criticizes Obama for claiming that reduced demand will lower prices. While Obama is wrong if he literally meant that reduced demand would mean lower gas prices, if he meant that increased efficiency would lower energy costs, then he is absolutely right. It costs half as much to drive a car a mile if it gets 40 miles a gallon than if it gets 20 miles a gallon.

One last point, Krauthammer is upset that President Obama is spending 0.0004 percent of the federal budget on research into using algae as a fuel source. If we cut this spending, that apparently Krauthammer knows to be foolish, we could rebate 5 cents to every person in the country.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

George Will has decided that it is unconstitutional for state and local governments to negotiate contracts with their workers that have the governments paying for some of the time of union staff. He found $900,000 of such payments in the Phoenix police contract and decided that is an unconstitutional gift.

It would be interesting to see how Will compares this to CEOs of companies that contract with the government paying themselves tens of millions of dollars a year. That might seem a much larger gift.

No doubt Will would say that companies negotiated a contract with the government and how the company choose to divide their money is their own business. However if he applied the logic consistently then he would end up with the exact same story with government workers.(Will also argues that the political power of public sector unions adds an element of corruption to this story. That doesn’t help his case much. Government contractors have also been known to make campaign contributions.)

When unions negotiate a contract that provides for payment of union officers they understand that they are giving up something in terms of wages or other compensation. In other words, the government does not negotiate a contract with workers and then say “hey, here’s another $900,000 to pay for union activities.” The money to cover the cost of running the union is coming out of compensation that workers would have otherwise earned.

That is the econ 101 lesson and that is why it is unlikely that any court would waste taxpayers money reviewing a lawsuit that is so obviously ridiculous. George Will obviously does not like unions, but he will have to do a bit more homework if he wants to make his case in court, although he has obviously done enough homework to make the Washington Post oped page.

George Will has decided that it is unconstitutional for state and local governments to negotiate contracts with their workers that have the governments paying for some of the time of union staff. He found $900,000 of such payments in the Phoenix police contract and decided that is an unconstitutional gift.

It would be interesting to see how Will compares this to CEOs of companies that contract with the government paying themselves tens of millions of dollars a year. That might seem a much larger gift.

No doubt Will would say that companies negotiated a contract with the government and how the company choose to divide their money is their own business. However if he applied the logic consistently then he would end up with the exact same story with government workers.(Will also argues that the political power of public sector unions adds an element of corruption to this story. That doesn’t help his case much. Government contractors have also been known to make campaign contributions.)

When unions negotiate a contract that provides for payment of union officers they understand that they are giving up something in terms of wages or other compensation. In other words, the government does not negotiate a contract with workers and then say “hey, here’s another $900,000 to pay for union activities.” The money to cover the cost of running the union is coming out of compensation that workers would have otherwise earned.

That is the econ 101 lesson and that is why it is unlikely that any court would waste taxpayers money reviewing a lawsuit that is so obviously ridiculous. George Will obviously does not like unions, but he will have to do a bit more homework if he wants to make his case in court, although he has obviously done enough homework to make the Washington Post oped page.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Simon Johnson had a nice blogpost in the NYT arguing that populism has often been a source of good economic ideas in U.S. history with a focus on populist sentiment for breaking up too big to fail banks. At one point Johnson notes some of the constructive measures pushed by populists, noting that the direct election of senators and the income tax were both populist ideas.

One other item that should be on this list is ending the gold standard. This was a rallying cry for the populists throughout their history. It was also good policy, as going off the gold standard laid the basis for the recovery from the Great Depression.

Simon Johnson had a nice blogpost in the NYT arguing that populism has often been a source of good economic ideas in U.S. history with a focus on populist sentiment for breaking up too big to fail banks. At one point Johnson notes some of the constructive measures pushed by populists, noting that the direct election of senators and the income tax were both populist ideas.

One other item that should be on this list is ending the gold standard. This was a rallying cry for the populists throughout their history. It was also good policy, as going off the gold standard laid the basis for the recovery from the Great Depression.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Clive Crook seems to want to both expand and privatize Social Security in part to address the real problem that retirees do not have enough money to have a decent standard of living. Before addressing his main policy proposal, it’s worth addressing a few things that he gets wrong.

First, he complains that the program is adding to the deficit, telling readers to:

“Forget the ‘trust fund’ and its holdings of government debt. That’s money the government owes to itself: It nets out to zero.”

Yes, I keep telling Peter Peterson to forget his holdings of government debt. That is simply money owed by the government.

Look, this is a real simple logical point. We keep a separate account for Social Security. Clive Crook and whoever else may not like that fact, but it happens to be reality.

That is why it is possible for Social Security to run out of money in a way that it is not possible for the Pentagon or State Department to run out of money. If Crook doesn’t believe in the idea of Social Security being a separate account then his next sentence is nonsense:

“What counts is that the system is now adding to the budget deficit, and will add more with time.”

If it’s all one budget, then every spending program adds to the deficit all the time. What Crook wants to do is to ignore the $2.7 trillion in government bonds that Social Security built up over the last quarter century by taxing workers more than was needed to pay benefits. This is known as “stealing.”

Crook then proposes two measures to eliminate projected shortfalls. One is to raise the retirement age. This proposal ignores the fact that many older workers, especially those with less education, work at physically demanding jobs where it will be difficult for them to work into their mid or late sixties.

His next proposal is means-testing. This one doesn’t make much sense once you look at the data. While Peter Peterson may not need his Social Security, there are not many billionaires collecting benefits. To have any noticeable impact on the program’s costs you would have to hit people with non-Social Security incomes of around $40k, and even then the gains would be limited.

However Crook is exactly right in saying that the current Social Security benefit is inadequate to support a decent retirement. To remedy this he proposes a mandatory contribution equal to 5 percent of wages to a new government-run retirement fund. (There would be subsidies for lower income workers, but Crook would probably leave many moderate-income workers hard hit with this 5 percent contribution.)

The idea of increasing the money put aside for retirement is fine, except he uses President Bush’s proposal for individual accounts as his model. Of course President Bush did not want to have collectively invested money, he wanted people to have their own accounts where they could play around with their money. This would have added cost and increased risk compared to what Crook is suggesting.

As far as Crook’s plan, it is not clear what the benefit is from having individuals get an investment return as opposed to a guaranteed benefit based on average returns. The difference is that the government need not worry about the timing of the market (it will survive through a down market), whereas individual workers have to worry a great deal about timing. If the government assumed this timing risk and paid workers an average return on their investment (e.g. 3.0 percent above the rate of inflation), then workers could avoid timing risk.

If there is a downside to going this route and upside to subjecting workers to the risk of market timing, it is hard to see what it is. Anyhow, Crook’s plan clearly is not going anywhere any time soon, but it is good to at least see someone recognizing the need to increase, rather than decrease, retirement income.

Clive Crook seems to want to both expand and privatize Social Security in part to address the real problem that retirees do not have enough money to have a decent standard of living. Before addressing his main policy proposal, it’s worth addressing a few things that he gets wrong.

First, he complains that the program is adding to the deficit, telling readers to:

“Forget the ‘trust fund’ and its holdings of government debt. That’s money the government owes to itself: It nets out to zero.”

Yes, I keep telling Peter Peterson to forget his holdings of government debt. That is simply money owed by the government.

Look, this is a real simple logical point. We keep a separate account for Social Security. Clive Crook and whoever else may not like that fact, but it happens to be reality.

That is why it is possible for Social Security to run out of money in a way that it is not possible for the Pentagon or State Department to run out of money. If Crook doesn’t believe in the idea of Social Security being a separate account then his next sentence is nonsense:

“What counts is that the system is now adding to the budget deficit, and will add more with time.”

If it’s all one budget, then every spending program adds to the deficit all the time. What Crook wants to do is to ignore the $2.7 trillion in government bonds that Social Security built up over the last quarter century by taxing workers more than was needed to pay benefits. This is known as “stealing.”

Crook then proposes two measures to eliminate projected shortfalls. One is to raise the retirement age. This proposal ignores the fact that many older workers, especially those with less education, work at physically demanding jobs where it will be difficult for them to work into their mid or late sixties.

His next proposal is means-testing. This one doesn’t make much sense once you look at the data. While Peter Peterson may not need his Social Security, there are not many billionaires collecting benefits. To have any noticeable impact on the program’s costs you would have to hit people with non-Social Security incomes of around $40k, and even then the gains would be limited.

However Crook is exactly right in saying that the current Social Security benefit is inadequate to support a decent retirement. To remedy this he proposes a mandatory contribution equal to 5 percent of wages to a new government-run retirement fund. (There would be subsidies for lower income workers, but Crook would probably leave many moderate-income workers hard hit with this 5 percent contribution.)

The idea of increasing the money put aside for retirement is fine, except he uses President Bush’s proposal for individual accounts as his model. Of course President Bush did not want to have collectively invested money, he wanted people to have their own accounts where they could play around with their money. This would have added cost and increased risk compared to what Crook is suggesting.

As far as Crook’s plan, it is not clear what the benefit is from having individuals get an investment return as opposed to a guaranteed benefit based on average returns. The difference is that the government need not worry about the timing of the market (it will survive through a down market), whereas individual workers have to worry a great deal about timing. If the government assumed this timing risk and paid workers an average return on their investment (e.g. 3.0 percent above the rate of inflation), then workers could avoid timing risk.

If there is a downside to going this route and upside to subjecting workers to the risk of market timing, it is hard to see what it is. Anyhow, Crook’s plan clearly is not going anywhere any time soon, but it is good to at least see someone recognizing the need to increase, rather than decrease, retirement income.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión