Adam Davidson has an interesting piece about how many low-paying jobs have a sort of lottery component where people are willing to accept low wages for a period of time in the hope that they will end up having a very high-paying job in the future. The best example of this sort of lottery system is probably the motion picture industry in Hollywood, where many people will spend years working in low-paying jobs in the hope that at some point they will make it big as an actor or director.

The piece then points out that many other occupations have a similar, if less extreme, lottery component. For example, lawyers are expected to work very hard as associates, but then can expect much higher pay if they get promoted to partner. Similarly, non-tenured faculty can face serious pressures to produce large amounts of research, before getting to enjoy the good life as a tenured faculty member.

Taking this view more broadly, most jobs have some sort of lottery component in the sense that there is a benefit to staying with a firm for a long period of time that workers lose if they leave, either by their choice or their employers. In more mundane jobs, the benefit might just be a pension, job security, and perhaps above-market pay for workers as they near retirement. The logic is that workers might get below-market pay when they are young and energetic, but if they stay with a firm long enough the situation is reversed as they slow down and their wage rises with seniority.

This point is interesting because it implies an obvious way that firms can increase their profit, at least in the short-term: take away the lottery prize. The savings on the prize is a pure short-term gain. In the case where a firm is keeping older, less productive, workers on the payroll and paying them a premium for seniority, ending the lottery prize (i.e. firing the workers) is a pure short-term gain. (This is of course a caricature — older workers are not necessarily less productive.) In the longer term it may not be a profit maximizing strategy, since younger workers will not make a commitment to mastering firm specific skills if they do not expect to be able to stay at the firm.

An article by Larry Summers and Andre Shliefer argued that breaking commitments of this sort was at the heart of the better-than-normal profits that private equity companies were able to earn. They argued that by breaking implicit contracts with workers and other stakeholders, private equity companies could increase profit at least in the short-run. If their intention is to sell out their stake at a profit, then a short-run gain would suit their purposes, even if the strategy might be harmful to the company and the economy in the long-run.

Adam Davidson has an interesting piece about how many low-paying jobs have a sort of lottery component where people are willing to accept low wages for a period of time in the hope that they will end up having a very high-paying job in the future. The best example of this sort of lottery system is probably the motion picture industry in Hollywood, where many people will spend years working in low-paying jobs in the hope that at some point they will make it big as an actor or director.

The piece then points out that many other occupations have a similar, if less extreme, lottery component. For example, lawyers are expected to work very hard as associates, but then can expect much higher pay if they get promoted to partner. Similarly, non-tenured faculty can face serious pressures to produce large amounts of research, before getting to enjoy the good life as a tenured faculty member.

Taking this view more broadly, most jobs have some sort of lottery component in the sense that there is a benefit to staying with a firm for a long period of time that workers lose if they leave, either by their choice or their employers. In more mundane jobs, the benefit might just be a pension, job security, and perhaps above-market pay for workers as they near retirement. The logic is that workers might get below-market pay when they are young and energetic, but if they stay with a firm long enough the situation is reversed as they slow down and their wage rises with seniority.

This point is interesting because it implies an obvious way that firms can increase their profit, at least in the short-term: take away the lottery prize. The savings on the prize is a pure short-term gain. In the case where a firm is keeping older, less productive, workers on the payroll and paying them a premium for seniority, ending the lottery prize (i.e. firing the workers) is a pure short-term gain. (This is of course a caricature — older workers are not necessarily less productive.) In the longer term it may not be a profit maximizing strategy, since younger workers will not make a commitment to mastering firm specific skills if they do not expect to be able to stay at the firm.

An article by Larry Summers and Andre Shliefer argued that breaking commitments of this sort was at the heart of the better-than-normal profits that private equity companies were able to earn. They argued that by breaking implicit contracts with workers and other stakeholders, private equity companies could increase profit at least in the short-run. If their intention is to sell out their stake at a profit, then a short-run gain would suit their purposes, even if the strategy might be harmful to the company and the economy in the long-run.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT told readers that a shortage of rental housing is driving up rents. This is wrong and wrong.

The NYT story is that the flood of foreclosures has forced people out of their homes and led them to look for rental housing. While this is true to some extent (homeownership rates have fallen), former homeowners would have discovered that there was a glut of rental housing.

Furthermore, ownership units can become rentals and vice-versa. This is true even for multi-family units, but 30 percent of rental properties nationwide are single family homes. These obviously can be converted very quickly to ownership units or more have been ownership units in the recent past.

So, if we look at the data on rental vacancy rates, we find that in the fourth quarter of 2011 the vacancy rate was 9.4 percent. This is down from the peak of 11.1 percent in the third quarter of 2009, but it is higher than any rate recorded in the 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, or 90s.

Turning to rents, the best measure to use is the Bureau Labor Statistics (BLS) measure for owner occupied housing. This measure will have some inertia, since it included all units, not just units that have been on the market. (There is more variation in price on units that are placed on the market.) However, it is more desirable than other measures because the BLS controls for quality changes and also because it only includes the rental value of the unit itself. It pulls out utilities which can have a large effect on rents, if they are included in a lease.

Year over Year Change in Owner Equivalent Rent

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, rents are increasing somewhat more rapidly than they were at the trough of the downturn, but they are still just rising pretty much in step with the rate of inflation. In fact the current rate of increase is lower than the rate of increase at any point in the decade prior to the beginning of the recession. While there may be some cities where rents are rising especially rapidly, or some narrow markets within cities, clearly this is not generally the case.

The NYT told readers that a shortage of rental housing is driving up rents. This is wrong and wrong.

The NYT story is that the flood of foreclosures has forced people out of their homes and led them to look for rental housing. While this is true to some extent (homeownership rates have fallen), former homeowners would have discovered that there was a glut of rental housing.

Furthermore, ownership units can become rentals and vice-versa. This is true even for multi-family units, but 30 percent of rental properties nationwide are single family homes. These obviously can be converted very quickly to ownership units or more have been ownership units in the recent past.

So, if we look at the data on rental vacancy rates, we find that in the fourth quarter of 2011 the vacancy rate was 9.4 percent. This is down from the peak of 11.1 percent in the third quarter of 2009, but it is higher than any rate recorded in the 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, or 90s.

Turning to rents, the best measure to use is the Bureau Labor Statistics (BLS) measure for owner occupied housing. This measure will have some inertia, since it included all units, not just units that have been on the market. (There is more variation in price on units that are placed on the market.) However, it is more desirable than other measures because the BLS controls for quality changes and also because it only includes the rental value of the unit itself. It pulls out utilities which can have a large effect on rents, if they are included in a lease.

Year over Year Change in Owner Equivalent Rent

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, rents are increasing somewhat more rapidly than they were at the trough of the downturn, but they are still just rising pretty much in step with the rate of inflation. In fact the current rate of increase is lower than the rate of increase at any point in the decade prior to the beginning of the recession. While there may be some cities where rents are rising especially rapidly, or some narrow markets within cities, clearly this is not generally the case.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Brooks tells readers that, if we count tax expenditures, the United States has a larger welfare state than many European countries, including Denmark, the Netherlands, and Finland. This is true, but it is important to understand what is being measured.

Brooks is looking at what we pay for social welfare expenditures, not what we get. This can be very different, as is most obviously the case with health care. As a share of its GDP, if we add in tax expenditures (e.g. the deduction for employer provided health insurance), the government in the United States commits a larger share of GDP for health care than almost anyone. (If we count government granted patent monopolies on prescription drugs and medical equipment, add in another percentage point of GDP.) Yet, unlike the European welfare states, the United States is still far from providing universal health insurance coverage.

In health care and other areas the United States is clearly paying for a welfare state. It is debatable whether it is getting one.

David Brooks tells readers that, if we count tax expenditures, the United States has a larger welfare state than many European countries, including Denmark, the Netherlands, and Finland. This is true, but it is important to understand what is being measured.

Brooks is looking at what we pay for social welfare expenditures, not what we get. This can be very different, as is most obviously the case with health care. As a share of its GDP, if we add in tax expenditures (e.g. the deduction for employer provided health insurance), the government in the United States commits a larger share of GDP for health care than almost anyone. (If we count government granted patent monopolies on prescription drugs and medical equipment, add in another percentage point of GDP.) Yet, unlike the European welfare states, the United States is still far from providing universal health insurance coverage.

In health care and other areas the United States is clearly paying for a welfare state. It is debatable whether it is getting one.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT did some heavy-duty he said/she said reporting on the issue of gas prices and energy production. It devoted an article to President Obama’s efforts to counter Republican complaints about high gas prices.

The article told readers:

“The president said that the United States is producing more oil now than at any time during the last eight years, with a record number of rigs pumping.”

President Obama did not just say this, it also happens to be true. There are reasons that people may not be happy that the United States is producing more oil (anyone hear of global warming?), but it happens to be true.

The article then went on to tell readers that:

“But Mr. Obama warned that no amount of domestic production could offset the broader forces driving up gas prices, chief among them Middle East instability and the ravenous energy appetite of China, which he said added 10 million cars in 2010.”

This is also a statement that can be verified. The United States currently produces around 6 million barrels a day. The world market for oil is a bit less than 90 million barrels a day.

It is the world market that determines prices, not domestic production. We’re going to say that a few more times just in case any reporters are reading this.

It is the world market that determines prices, not domestic production. It is the world market that determines prices, not domestic production. It is the world market that determines prices, not domestic production.

The point is that we can only affect the price of gas in the United States if we can affect world prices. See, if we had lower prices in the United States than the rest of the world, oil companies like Exxon Mobil and British Petroleum would export oil from the United States to the rest of the world.

This is known as “capitalism.” Companies try to make as much money as possible, which means that you sell your products where they can get the highest price. This means that the price of oil in the United States can only fall if the price of oil in the world also falls.

Okay, so now let’s get back to domestic production. Suppose we drill everywhere — underneath Yellowstone, the Capitol building, your backyard and favorite place of worship. Let’s say we can increase domestic production by 2 million barrels a day, or roughly one third. This would increase the world supply by approximately 2.2 percent.

Under normal assumptions of elasticity of supply and demand, this would lead to a drop in prices of around 6 percent. That might be nice, but it won’t get us from $4.00 a gallon gas to Newt Gingrich’s $2 a gallon.

Furthermore, we will not be able to sustain this higher pace of production for long. The Energy Information Agency estimates that total U.S. reserves are around 20 billion barrels of oil. At the current production rate of roughly 6 million barrels a day, this stock will last around 10 years. If we upped production to 8 million barrels a day then we have around 7 years supply. That would mean that production would have to slow sharply before the end of President Drill Everywhere’s second term.

In short, President Obama was making assertions about gas prices and energy that are true and can be proven. The NYT obviously assumed that readers have more time than its reporter to go to the web and look these things up, but that may not always be true.

Addendum:

The Post committed the same sin, telling readers:

“Obama’s position reflects the White House’s belief that gasoline prices are subject to cyclical spikes due to forces largely outside its control, including the rise in Chinese and Indian oil demand.”

Yes, the White House believes that, “gasoline prices are subject to cyclical spikes due to forces largely outside its control, including the rise in Chinese and Indian oil demand,” in the same way that it probably believes that the earth goes around the sun and gravity causes things to fall down. This happens to be true.

The NYT did some heavy-duty he said/she said reporting on the issue of gas prices and energy production. It devoted an article to President Obama’s efforts to counter Republican complaints about high gas prices.

The article told readers:

“The president said that the United States is producing more oil now than at any time during the last eight years, with a record number of rigs pumping.”

President Obama did not just say this, it also happens to be true. There are reasons that people may not be happy that the United States is producing more oil (anyone hear of global warming?), but it happens to be true.

The article then went on to tell readers that:

“But Mr. Obama warned that no amount of domestic production could offset the broader forces driving up gas prices, chief among them Middle East instability and the ravenous energy appetite of China, which he said added 10 million cars in 2010.”

This is also a statement that can be verified. The United States currently produces around 6 million barrels a day. The world market for oil is a bit less than 90 million barrels a day.

It is the world market that determines prices, not domestic production. We’re going to say that a few more times just in case any reporters are reading this.

It is the world market that determines prices, not domestic production. It is the world market that determines prices, not domestic production. It is the world market that determines prices, not domestic production.

The point is that we can only affect the price of gas in the United States if we can affect world prices. See, if we had lower prices in the United States than the rest of the world, oil companies like Exxon Mobil and British Petroleum would export oil from the United States to the rest of the world.

This is known as “capitalism.” Companies try to make as much money as possible, which means that you sell your products where they can get the highest price. This means that the price of oil in the United States can only fall if the price of oil in the world also falls.

Okay, so now let’s get back to domestic production. Suppose we drill everywhere — underneath Yellowstone, the Capitol building, your backyard and favorite place of worship. Let’s say we can increase domestic production by 2 million barrels a day, or roughly one third. This would increase the world supply by approximately 2.2 percent.

Under normal assumptions of elasticity of supply and demand, this would lead to a drop in prices of around 6 percent. That might be nice, but it won’t get us from $4.00 a gallon gas to Newt Gingrich’s $2 a gallon.

Furthermore, we will not be able to sustain this higher pace of production for long. The Energy Information Agency estimates that total U.S. reserves are around 20 billion barrels of oil. At the current production rate of roughly 6 million barrels a day, this stock will last around 10 years. If we upped production to 8 million barrels a day then we have around 7 years supply. That would mean that production would have to slow sharply before the end of President Drill Everywhere’s second term.

In short, President Obama was making assertions about gas prices and energy that are true and can be proven. The NYT obviously assumed that readers have more time than its reporter to go to the web and look these things up, but that may not always be true.

Addendum:

The Post committed the same sin, telling readers:

“Obama’s position reflects the White House’s belief that gasoline prices are subject to cyclical spikes due to forces largely outside its control, including the rise in Chinese and Indian oil demand.”

Yes, the White House believes that, “gasoline prices are subject to cyclical spikes due to forces largely outside its control, including the rise in Chinese and Indian oil demand,” in the same way that it probably believes that the earth goes around the sun and gravity causes things to fall down. This happens to be true.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A front page article on President Obama’s plan to cut the corporate tax rate to 28 percent from 35 percent, with offsetting eliminations of loopholes told readers in the second paragraph:

“Obama released a long-awaited plan to overhaul the nation’s corporate tax code that plays directly to his base.” [This line only appeared in the article that appears on-line as the print edition.] The bulk of Democrats have not been clamoring for a cut in the corporate tax rate, although many people in corporations have.

Later in the piece the article tells readers that the plan should increase corporate tax revenue by $250 billion over the course of the decade. Since most readers do not know how much the baseline shows for tax revenue over this period, this number does not provide any real information.

The current projections from the Congressional Budget Office show the government collecting $4,360 billion in corporate taxes over the decade. This means that the proposed increase would raise projected revenue by less than 6 percent.

A front page article on President Obama’s plan to cut the corporate tax rate to 28 percent from 35 percent, with offsetting eliminations of loopholes told readers in the second paragraph:

“Obama released a long-awaited plan to overhaul the nation’s corporate tax code that plays directly to his base.” [This line only appeared in the article that appears on-line as the print edition.] The bulk of Democrats have not been clamoring for a cut in the corporate tax rate, although many people in corporations have.

Later in the piece the article tells readers that the plan should increase corporate tax revenue by $250 billion over the course of the decade. Since most readers do not know how much the baseline shows for tax revenue over this period, this number does not provide any real information.

The current projections from the Congressional Budget Office show the government collecting $4,360 billion in corporate taxes over the decade. This means that the proposed increase would raise projected revenue by less than 6 percent.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Germany, like many other countries, restricts the ability of businesses to operate on Sunday and holidays. One of the main reasons for such restrictions is to ensure that workers will have the opportunity to spend time on these days with their families.

The New York Times is very unhappy about such policies. It devoted a major news article to criticizing this sort of “overregulation” in the German economy.

While it is arguable that Germany would be better off without restrictive hours for business operation and some of the other regulations cited in the article, these regulations do serve a purpose. Remarkably the article did not include the views of a single person defending these regulations. This is especially strange, since obviously the regulations all have a substantial base of support within Germany, otherwise they would not still exist.

This article also misled readers about Germany’s unemployment rate, reporting it as 7.3 percent. This is the unemployment rate using a German government measure that counts part-time workers as being unemployed.

The OECD publishes a harmonized unemployment rate that is calculated along the same lines as the unemployment rate in the United States. According to the OECD measure, the unemployment rate in Germany is 5.5 percent.

There is no excuse not to use the OECD measure when reporting on Germany’s unemployment rate. Using the German government measure without an explanation of the difference in methodology is grossly misleading and should never be done.

Germany, like many other countries, restricts the ability of businesses to operate on Sunday and holidays. One of the main reasons for such restrictions is to ensure that workers will have the opportunity to spend time on these days with their families.

The New York Times is very unhappy about such policies. It devoted a major news article to criticizing this sort of “overregulation” in the German economy.

While it is arguable that Germany would be better off without restrictive hours for business operation and some of the other regulations cited in the article, these regulations do serve a purpose. Remarkably the article did not include the views of a single person defending these regulations. This is especially strange, since obviously the regulations all have a substantial base of support within Germany, otherwise they would not still exist.

This article also misled readers about Germany’s unemployment rate, reporting it as 7.3 percent. This is the unemployment rate using a German government measure that counts part-time workers as being unemployed.

The OECD publishes a harmonized unemployment rate that is calculated along the same lines as the unemployment rate in the United States. According to the OECD measure, the unemployment rate in Germany is 5.5 percent.

There is no excuse not to use the OECD measure when reporting on Germany’s unemployment rate. Using the German government measure without an explanation of the difference in methodology is grossly misleading and should never be done.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Allan Sloan is a conscientious columnist with whom I occasionally have serious disagreements. The finances of Social Security is one of those occasions.

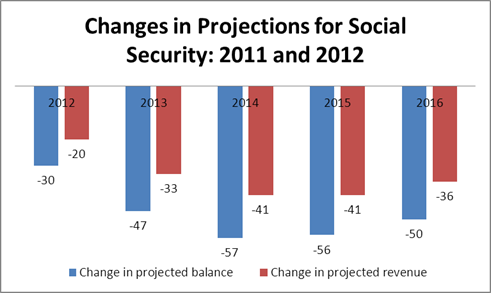

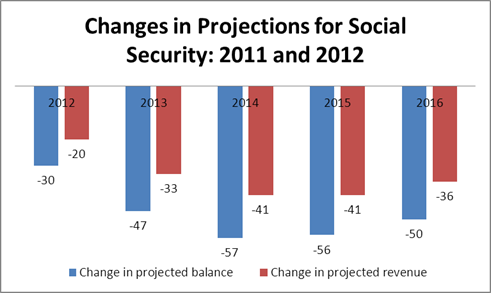

Sloan’s Fortune column this week provides one of those occasions. The focus is the deterioration in the near-term projections for Social Security. Sloan compares the 2011 Social Security Trustees report with the 2012 projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and finds a worsening of $300 billion in the projected cash flow of the trust fund over the next five years. He argues that this strengthens the case for measures to shore up the program’s finances. There are three slightly technical points on Sloan’s analysis that are worth making and then one substantive point.

First, Sloan compares sources that use somewhat different assumptions when comparing the Trustees numbers with the CBO numbers. The 2011 CBO numbers would have shown a somewhat worse picture than the 2011 Trustees numbers. If we compare the 2012 CBO numbers with the 2011 CBO numbers we can see the extent to which the situation has deteriorated due to a worsening economic outlook.

This doesn’t change the picture hugely, but it does make the deterioration somewhat less severe. The difference in the projected shortfall for the years 2012-2016 is $240 billion rather than the $300 billion using the 2011 Trustees numbers as the basis for comparison. (The Disability Trust Fund is projected to be depleted in 2016, so CBO does not project revenue and spending in that year. I have imputed a shortfall of $45 billion, the same as the prior two years.)

A second item worth noting is that the deterioration is mostly on the revenue side. Sloan attributes the problem to higher-than-projected cost-of-living adjustments that resulted from the jump in oil prices. While this is a factor, most of the story is on the revenue side.

Source: CBO 2011 and 2012.

This matters because the main reason that revenue is projected to be lower in 2012 than in 2011 is that unemployment is now projected to be higher and wage growth is projected to be lower. This once again shows the importance for Social Security of having adults in charge of managing the economy. When the economy does badly, Social Security’s finances do badly (repeat 256,000 times).

The third point worth noting in this story is the extent to which the deterioration in the projections from 2011 to 2012 is due to the disability portion of the program. With my imputation for 2016, the worsening finances of disability accounted for $49 billion of the $240 billion deterioration in the program’s projections from 2011 to 2012. This means that a program that receives just 14.5 percent of the program’s revenue accounted for 20.4 percent of the deterioration in finances.

This is not a new story. The cost of the disability program has been rising considerably more rapidly than had previously been projected throughout this downturn. There are not conclusive answers as to why this is the case, but it seems pretty clear that a prolonged period of high unemployment is a big part of the story. In a strong economy, people who have various physical and psychological problems may be able to hold onto their jobs until retirement. (Most of the disabled are older workers.) In a weak economy many of these people may lose their jobs and be unable to find new ones. The moral of the story is again the need to have adults running the economy.

Finally there is the substantive issue about the urgency of a Social Security fix. I see little urgency for two reasons. The first reason is that at a time when we are still down close to 10 million jobs from where the economy should be, the first, second, and third priority of policymakers should be job creation. In principle, Congress and the president can do more than one thing at a time, but this is Washington that we are talking about.

The second reason why I see no urgency for a Social Security fix is that the program is still fundamentally sound. According to the latest projections from CBO we still have more than a quarter-century before the fund will first face a shortfall. Even after that date the program would still be able to pay more than 80 percent of projected benefits, which would be more than current beneficiaries receive.

The eventual fix for Social Security will inevitably involve some mix of revenue increases and benefit cuts. There has been a well-financed campaign over the last few decades to convince the public that the program’s finances are far worse than is in fact the case. (A payroll tax increase equal to one-twentieth of projected wage growth over the next four decades would be more than enough to keep the program fully solvent past the end of the century.)

The lack of confidence in Social Security’s finances created by this misinformation campaign may cause the public to accept much larger cuts than if they realized the program’s true financial state. Therefore it makes sense to delay any major changes in the hope that the public will be better informed about the program in the future. (Peter Peterson will eventually run out of money.)

So the word for the day is “relax” – Social Security is fine for long into the future. Folks should instead spend their time yelling about the lack of adequate stimulus, insufficient measures from the Fed, and an over-valued dollar.

Allan Sloan is a conscientious columnist with whom I occasionally have serious disagreements. The finances of Social Security is one of those occasions.

Sloan’s Fortune column this week provides one of those occasions. The focus is the deterioration in the near-term projections for Social Security. Sloan compares the 2011 Social Security Trustees report with the 2012 projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and finds a worsening of $300 billion in the projected cash flow of the trust fund over the next five years. He argues that this strengthens the case for measures to shore up the program’s finances. There are three slightly technical points on Sloan’s analysis that are worth making and then one substantive point.

First, Sloan compares sources that use somewhat different assumptions when comparing the Trustees numbers with the CBO numbers. The 2011 CBO numbers would have shown a somewhat worse picture than the 2011 Trustees numbers. If we compare the 2012 CBO numbers with the 2011 CBO numbers we can see the extent to which the situation has deteriorated due to a worsening economic outlook.

This doesn’t change the picture hugely, but it does make the deterioration somewhat less severe. The difference in the projected shortfall for the years 2012-2016 is $240 billion rather than the $300 billion using the 2011 Trustees numbers as the basis for comparison. (The Disability Trust Fund is projected to be depleted in 2016, so CBO does not project revenue and spending in that year. I have imputed a shortfall of $45 billion, the same as the prior two years.)

A second item worth noting is that the deterioration is mostly on the revenue side. Sloan attributes the problem to higher-than-projected cost-of-living adjustments that resulted from the jump in oil prices. While this is a factor, most of the story is on the revenue side.

Source: CBO 2011 and 2012.

This matters because the main reason that revenue is projected to be lower in 2012 than in 2011 is that unemployment is now projected to be higher and wage growth is projected to be lower. This once again shows the importance for Social Security of having adults in charge of managing the economy. When the economy does badly, Social Security’s finances do badly (repeat 256,000 times).

The third point worth noting in this story is the extent to which the deterioration in the projections from 2011 to 2012 is due to the disability portion of the program. With my imputation for 2016, the worsening finances of disability accounted for $49 billion of the $240 billion deterioration in the program’s projections from 2011 to 2012. This means that a program that receives just 14.5 percent of the program’s revenue accounted for 20.4 percent of the deterioration in finances.

This is not a new story. The cost of the disability program has been rising considerably more rapidly than had previously been projected throughout this downturn. There are not conclusive answers as to why this is the case, but it seems pretty clear that a prolonged period of high unemployment is a big part of the story. In a strong economy, people who have various physical and psychological problems may be able to hold onto their jobs until retirement. (Most of the disabled are older workers.) In a weak economy many of these people may lose their jobs and be unable to find new ones. The moral of the story is again the need to have adults running the economy.

Finally there is the substantive issue about the urgency of a Social Security fix. I see little urgency for two reasons. The first reason is that at a time when we are still down close to 10 million jobs from where the economy should be, the first, second, and third priority of policymakers should be job creation. In principle, Congress and the president can do more than one thing at a time, but this is Washington that we are talking about.

The second reason why I see no urgency for a Social Security fix is that the program is still fundamentally sound. According to the latest projections from CBO we still have more than a quarter-century before the fund will first face a shortfall. Even after that date the program would still be able to pay more than 80 percent of projected benefits, which would be more than current beneficiaries receive.

The eventual fix for Social Security will inevitably involve some mix of revenue increases and benefit cuts. There has been a well-financed campaign over the last few decades to convince the public that the program’s finances are far worse than is in fact the case. (A payroll tax increase equal to one-twentieth of projected wage growth over the next four decades would be more than enough to keep the program fully solvent past the end of the century.)

The lack of confidence in Social Security’s finances created by this misinformation campaign may cause the public to accept much larger cuts than if they realized the program’s true financial state. Therefore it makes sense to delay any major changes in the hope that the public will be better informed about the program in the future. (Peter Peterson will eventually run out of money.)

So the word for the day is “relax” – Social Security is fine for long into the future. Folks should instead spend their time yelling about the lack of adequate stimulus, insufficient measures from the Fed, and an over-valued dollar.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is what readers of a piece on the Fed’s recommendations for housing policy are likely to take away. At one point the article comments:

“More than perhaps any other federal agency, the Fed was established to operate independently of both the president and Congress so that it would be free of political pressures when judging what’s best for the economy.”

What is most extraordinary about the Fed is the fact that it includes the industry it oversees, the banking industry, with the ability to appoint members of its governing buddy. While other regulatory bodies, like the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Communications Commission, are subject to influence by industry lobbyists, the 12 heads of the Federal Reserve Board’s district banks are essentially appointed by the banks.

These bank heads in turn play a direct role in setting monetary policy, with 5 of the 12 sitting as voting members of the Open Market Committee, the body that sets monetary policy. The other 7 also take part in meetings, but do not have a vote. The influence of the banking industry on the Fed’s conduct does make it more independent of democratic control, but it does not follow that it leads it to do what is “best for the economy.”

Also, those reading this article may conclude that the Post still has not heard about the housing bubble. At one point it told readers:

“These policies [the Fed’s low interest rate policy, coupled with its quantitative easing] should be making it easier for people to buy homes, launching a virtuous cycle of rising housing prices and fewer foreclosures.”

The housing bubble has been in a process of deflating for the last 5 and a half years. Nationwide, house prices are just now returning to their trend levels. No one has presented any research that suggests that house prices should return to their bubble-inflated levels as the Post’s comments seem to imply. In reality, we should expect house prices to stabilize near their current level and then roughly rise in step with inflation, as they have done for more than 100 years.

That is what readers of a piece on the Fed’s recommendations for housing policy are likely to take away. At one point the article comments:

“More than perhaps any other federal agency, the Fed was established to operate independently of both the president and Congress so that it would be free of political pressures when judging what’s best for the economy.”

What is most extraordinary about the Fed is the fact that it includes the industry it oversees, the banking industry, with the ability to appoint members of its governing buddy. While other regulatory bodies, like the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Communications Commission, are subject to influence by industry lobbyists, the 12 heads of the Federal Reserve Board’s district banks are essentially appointed by the banks.

These bank heads in turn play a direct role in setting monetary policy, with 5 of the 12 sitting as voting members of the Open Market Committee, the body that sets monetary policy. The other 7 also take part in meetings, but do not have a vote. The influence of the banking industry on the Fed’s conduct does make it more independent of democratic control, but it does not follow that it leads it to do what is “best for the economy.”

Also, those reading this article may conclude that the Post still has not heard about the housing bubble. At one point it told readers:

“These policies [the Fed’s low interest rate policy, coupled with its quantitative easing] should be making it easier for people to buy homes, launching a virtuous cycle of rising housing prices and fewer foreclosures.”

The housing bubble has been in a process of deflating for the last 5 and a half years. Nationwide, house prices are just now returning to their trend levels. No one has presented any research that suggests that house prices should return to their bubble-inflated levels as the Post’s comments seem to imply. In reality, we should expect house prices to stabilize near their current level and then roughly rise in step with inflation, as they have done for more than 100 years.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In his Economix piece this week, Casey Mulligan picks up on his theme from last week that unemployment insurance (UI) benefits may not boost spending in aggregate, since the money needed to pay benefits is withdrawn from other spending. He agrees with my earlier point that the money is not coming from current tax revenue, but rather from deficit financing, then says that:

“But that ‘financing channel’ still does not make the payments free from the perspective of today’s economy.

“Suppose the government has been borrowing the money to pay for unemployment benefits. It borrows money by selling bonds. The purchasers of those bonds have less to spend on something else.”

Actually, most or all of the money that would be used to buy the bonds is a reallocation from other savings, at least at a time like the present when the economy is in a serious downturn. In effect, bond buyers will use either deposits or sales of other assets (e.g. stocks or bonds of private companies) to buy up government bonds. This has no direct effect on their consumption.

In other times this could lead to an increase in interest rates, which would discourage other spending to some extent, however this effect is likely to be trivial or altogether non-existent in the current environment. Banks have vast amounts of excess reserves sitting idle. The government’s sale of bonds will likely pull in some of these excess reserves. If UI benefits are associated with a boost to growth, and therefore more total deposits, then the net amount of excess reserves in the system may decline slightly, but as long as we still have vast amounts excess reserves, the impact on the interest rate will be trivial, as will the impact on spending.

The extreme case can be seen when the Fed is the buyer of the bonds. In that case, there would actually be an increase in the excess reserves of the system as a result of the government’s sale of bonds, and therefore no increase, and possibly even a decrease, in interest rates. In that case, the government spending is a pure gain to demand and to the economy.

In this scenario, safety net spending boosts growth and employment. It does not impose a cost on the rest of us. More generally, it makes sense to think of UI benefits and other safety net programs as being like other forms of insurance. We pay some price for it in the good times — output is somewhat lower than it otherwise would be — so that we can be protected in the bad times.

This means that in the bad times (e.g. your house burns down) insurance is unambiguously beneficial. Whether it is providing good value over the good and bad times taken together depends on the exact conditions of the policy.

In his Economix piece this week, Casey Mulligan picks up on his theme from last week that unemployment insurance (UI) benefits may not boost spending in aggregate, since the money needed to pay benefits is withdrawn from other spending. He agrees with my earlier point that the money is not coming from current tax revenue, but rather from deficit financing, then says that:

“But that ‘financing channel’ still does not make the payments free from the perspective of today’s economy.

“Suppose the government has been borrowing the money to pay for unemployment benefits. It borrows money by selling bonds. The purchasers of those bonds have less to spend on something else.”

Actually, most or all of the money that would be used to buy the bonds is a reallocation from other savings, at least at a time like the present when the economy is in a serious downturn. In effect, bond buyers will use either deposits or sales of other assets (e.g. stocks or bonds of private companies) to buy up government bonds. This has no direct effect on their consumption.

In other times this could lead to an increase in interest rates, which would discourage other spending to some extent, however this effect is likely to be trivial or altogether non-existent in the current environment. Banks have vast amounts of excess reserves sitting idle. The government’s sale of bonds will likely pull in some of these excess reserves. If UI benefits are associated with a boost to growth, and therefore more total deposits, then the net amount of excess reserves in the system may decline slightly, but as long as we still have vast amounts excess reserves, the impact on the interest rate will be trivial, as will the impact on spending.

The extreme case can be seen when the Fed is the buyer of the bonds. In that case, there would actually be an increase in the excess reserves of the system as a result of the government’s sale of bonds, and therefore no increase, and possibly even a decrease, in interest rates. In that case, the government spending is a pure gain to demand and to the economy.

In this scenario, safety net spending boosts growth and employment. It does not impose a cost on the rest of us. More generally, it makes sense to think of UI benefits and other safety net programs as being like other forms of insurance. We pay some price for it in the good times — output is somewhat lower than it otherwise would be — so that we can be protected in the bad times.

This means that in the bad times (e.g. your house burns down) insurance is unambiguously beneficial. Whether it is providing good value over the good and bad times taken together depends on the exact conditions of the policy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In his column on the mortgage settlement last weekend Joe Nocera praised the fact that it would mean that more people would be able to stay in their homes and that some compensation will be paid to foreclosed homeowners in situations where the banks did not follow the rules. He also criticized those on the left who criticized the deal “before the ink was dry.”

Of course there was a reason to criticize the deal before the ink was dry. The settlement was announced before it was actually finalized. That meant that if the critics wanted to get their views into the same news cycle they had no choice except to criticize a settlement before the ink was even wet. Nocera’s criticism would be better directed at the attorneys general’s effort to manipulate the news coverage of the settlement.

There are many issues that can be debated about the settlement, but there are three big ones that stand out:

1) It is not clear what baseline is being used to determine how much is being paid. The banks are already doing some amount of modifications, principal reductions, and short sales. It is not clear how it will be determined that they are going beyond what they would have done anyhow as a result of the settlement. This means that it will be difficult to determine that the $17 billion in write-downs stipulated in the settlement have actually taken place.

2) The banks will be able to count write-downs of loans that they are servicing against this sum. These losses will come out of the pockets of the investors in mortgage backed securities, not the banks’ pockets. This means that the defendant in a civil case is effectively being allowed to pay its penalty with someone else’s money. This is at the least unusual.

3) It is far from clear that the foreclosure abuses that are the basis for the case have been put to an end. An audit of 400 recent foreclosures conducted in San Francisco County indicates that abuses are still pervasive. It is unclear that the servicers are prepared to change their practices and that the attorneys general will take further steps if they do not.

There are many other reasons for criticizing the settlement, but those are my big three. These points were not acknowledged in Nocera’s column praising the settlement.

In his column on the mortgage settlement last weekend Joe Nocera praised the fact that it would mean that more people would be able to stay in their homes and that some compensation will be paid to foreclosed homeowners in situations where the banks did not follow the rules. He also criticized those on the left who criticized the deal “before the ink was dry.”

Of course there was a reason to criticize the deal before the ink was dry. The settlement was announced before it was actually finalized. That meant that if the critics wanted to get their views into the same news cycle they had no choice except to criticize a settlement before the ink was even wet. Nocera’s criticism would be better directed at the attorneys general’s effort to manipulate the news coverage of the settlement.

There are many issues that can be debated about the settlement, but there are three big ones that stand out:

1) It is not clear what baseline is being used to determine how much is being paid. The banks are already doing some amount of modifications, principal reductions, and short sales. It is not clear how it will be determined that they are going beyond what they would have done anyhow as a result of the settlement. This means that it will be difficult to determine that the $17 billion in write-downs stipulated in the settlement have actually taken place.

2) The banks will be able to count write-downs of loans that they are servicing against this sum. These losses will come out of the pockets of the investors in mortgage backed securities, not the banks’ pockets. This means that the defendant in a civil case is effectively being allowed to pay its penalty with someone else’s money. This is at the least unusual.

3) It is far from clear that the foreclosure abuses that are the basis for the case have been put to an end. An audit of 400 recent foreclosures conducted in San Francisco County indicates that abuses are still pervasive. It is unclear that the servicers are prepared to change their practices and that the attorneys general will take further steps if they do not.

There are many other reasons for criticizing the settlement, but those are my big three. These points were not acknowledged in Nocera’s column praising the settlement.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión