In a front page piece, the Post asked why, given the economy’s recovery, so many less-educated workers don’t have jobs? There is a very simple answer that could have saved the lives of many trees. The economy has not recovered much. While the unemployment rate has fallen by almost two percentage points from its peak in late 2009, the employment rate (EPOP), the percentage of people with jobs has risen by just 0.6 percentage points. (This adjusts for a change in population controls that reduced the EPOP by 0.3 percentage points from December to January.)

This means that almost two-thirds of the drop in the unemployment rate has been due to people dropping out of the workforce (and therefore not being counted as unemployed), not people getting jobs. Measured in terms of employment, the economy has improved very little from its trough, therefore it is not surprising that less-educated workers, like more educated workers, are still having difficulty finding jobs.

The unemployment rate for the 30 percent of the workforce with college degrees is still more than twice its pre-recession level. If the Post had done its homework it would know that the problem is not the skill levels of unemployed workers, the problem is the skill level of people who make economic policy.

Employment to Population Ratio

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In a front page piece, the Post asked why, given the economy’s recovery, so many less-educated workers don’t have jobs? There is a very simple answer that could have saved the lives of many trees. The economy has not recovered much. While the unemployment rate has fallen by almost two percentage points from its peak in late 2009, the employment rate (EPOP), the percentage of people with jobs has risen by just 0.6 percentage points. (This adjusts for a change in population controls that reduced the EPOP by 0.3 percentage points from December to January.)

This means that almost two-thirds of the drop in the unemployment rate has been due to people dropping out of the workforce (and therefore not being counted as unemployed), not people getting jobs. Measured in terms of employment, the economy has improved very little from its trough, therefore it is not surprising that less-educated workers, like more educated workers, are still having difficulty finding jobs.

The unemployment rate for the 30 percent of the workforce with college degrees is still more than twice its pre-recession level. If the Post had done its homework it would know that the problem is not the skill levels of unemployed workers, the problem is the skill level of people who make economic policy.

Employment to Population Ratio

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post columnist Charles Lane has decided that public sector unions are undemocratic. This will be a surprise to every democracy in the world, since all of them have public sector unions.

The basic argument seems to be that since unions prevent elected officials from paying as little as they miight want to their workers, they interfere with democracy. This is a bit hard to follow. If a pension fund manager refuses to manage the state’s pension fund for a $100 an hour wage, or a doctor refuses to work for $50 an hour for Medicaid, are these people interfering with democracy because they are not accepting the pay offered by an elected official?

Lane then complains that public sector unions make campaign contributions to the state officials with whom they negotiate. This is a reasonable complaint for someone who knows nothing about U.S. politics. It is standard for all sorts of people who do business with the government (e.g. defense contractors, construction companies, pension fund managers) to make campaign contributions to the people with whom they negotiate. It might not be pretty, but this is a problem that goes well beyond unions.

Lane then complains about the “rubber rooms” demanded by NYC in its negotiations with the teacher unions. The city required that teachers awaiting hearings on discipline charges come to school and sit for 8 hours a day. This may be stupid, as Lane suggests, but his complaint is with the city, not the union.

If Lane thinks that unions are an obstacle to good education then he needs to do more homework. Nordic countries like Finland, that rank at the top in most education measures, have much higher unionization rates among their teachers than the U.S. This suggests that the problem is more likely to lie with the Lane’s friends on the other side of the negotiating table.

Lane is also confused about basic economics. He complains that the clout of public sector unions allow their members:

“to enjoy retirement and health-care benefits that are often better than those available to the middle-class citizens whose tax dollars support them” adding “even after Walker’s bill, Wisconsin public employees pay just 5.8 percent of their salary toward their pensions and a modest 12.6 percent of their health-care premiums.”

In economics, we look at a workers’ total compensation packages. It is understood that benefits that are ostensibly paid by employers are a trade-off for higher wages. When the total compensation packages of public sector workers are compared to those with comparable education and experience in the private sector, they actually get somewhat lower pay.

Washington Post columnist Charles Lane has decided that public sector unions are undemocratic. This will be a surprise to every democracy in the world, since all of them have public sector unions.

The basic argument seems to be that since unions prevent elected officials from paying as little as they miight want to their workers, they interfere with democracy. This is a bit hard to follow. If a pension fund manager refuses to manage the state’s pension fund for a $100 an hour wage, or a doctor refuses to work for $50 an hour for Medicaid, are these people interfering with democracy because they are not accepting the pay offered by an elected official?

Lane then complains that public sector unions make campaign contributions to the state officials with whom they negotiate. This is a reasonable complaint for someone who knows nothing about U.S. politics. It is standard for all sorts of people who do business with the government (e.g. defense contractors, construction companies, pension fund managers) to make campaign contributions to the people with whom they negotiate. It might not be pretty, but this is a problem that goes well beyond unions.

Lane then complains about the “rubber rooms” demanded by NYC in its negotiations with the teacher unions. The city required that teachers awaiting hearings on discipline charges come to school and sit for 8 hours a day. This may be stupid, as Lane suggests, but his complaint is with the city, not the union.

If Lane thinks that unions are an obstacle to good education then he needs to do more homework. Nordic countries like Finland, that rank at the top in most education measures, have much higher unionization rates among their teachers than the U.S. This suggests that the problem is more likely to lie with the Lane’s friends on the other side of the negotiating table.

Lane is also confused about basic economics. He complains that the clout of public sector unions allow their members:

“to enjoy retirement and health-care benefits that are often better than those available to the middle-class citizens whose tax dollars support them” adding “even after Walker’s bill, Wisconsin public employees pay just 5.8 percent of their salary toward their pensions and a modest 12.6 percent of their health-care premiums.”

In economics, we look at a workers’ total compensation packages. It is understood that benefits that are ostensibly paid by employers are a trade-off for higher wages. When the total compensation packages of public sector workers are compared to those with comparable education and experience in the private sector, they actually get somewhat lower pay.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

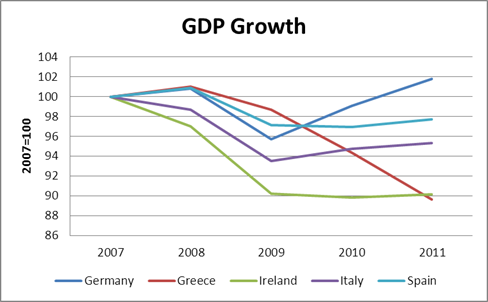

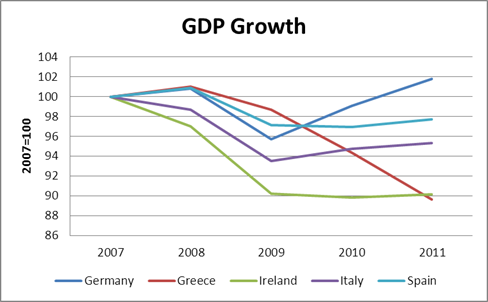

A chart that accompanied an article about negotiations on Greece’s debt showed that GDP had risen since 2007 in all the crisis countries except Ireland. This is not true. GDP is down in all of the crisis countries,

Source: IMF.

It appears that the chart in the NYT is showing nominal GDP. This has risen since 2007 but only as a result of higher prices. Real GDP has fallen in all five crisis countries. (Sorry, I left off Portugal.)

A chart that accompanied an article about negotiations on Greece’s debt showed that GDP had risen since 2007 in all the crisis countries except Ireland. This is not true. GDP is down in all of the crisis countries,

Source: IMF.

It appears that the chart in the NYT is showing nominal GDP. This has risen since 2007 but only as a result of higher prices. Real GDP has fallen in all five crisis countries. (Sorry, I left off Portugal.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Bill Keller tells readers that Congress should pass laws that require intermediaries like Google and Wikipedia to take responsibility for helping to enforce copyrights. It is interesting to see how he thinks the wording of the Article 1, Section 8:

“To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries”

which gives Congress the power to grant copyright and patent monopolies, also authorizes Congress to require that individuals and companies assist others in enforcement of their copyrights. Can Congress require that people help me make a profit on my hotdog stand?

If the development of technology makes copyright and inefficient way to “promote the progress of science and useful arts,” then the constitutional route for dealing with the situation would be to find more efficient mechanisms to serve this purpose.

This might be difficult in the United States. There have been numerous news stories and columns decrying the shortage of workers with the necessary skills. In this case, the skill in short supply is the ability to think creatively about an effective response to developments in technology.

Anyhow, it is perverse response to the development of technology to grant the government ever greater powers of repression in order to ensure that an archaic social institution can still be used to generate profits for a small group of powerful corporations and individuals.

Bill Keller tells readers that Congress should pass laws that require intermediaries like Google and Wikipedia to take responsibility for helping to enforce copyrights. It is interesting to see how he thinks the wording of the Article 1, Section 8:

“To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries”

which gives Congress the power to grant copyright and patent monopolies, also authorizes Congress to require that individuals and companies assist others in enforcement of their copyrights. Can Congress require that people help me make a profit on my hotdog stand?

If the development of technology makes copyright and inefficient way to “promote the progress of science and useful arts,” then the constitutional route for dealing with the situation would be to find more efficient mechanisms to serve this purpose.

This might be difficult in the United States. There have been numerous news stories and columns decrying the shortage of workers with the necessary skills. In this case, the skill in short supply is the ability to think creatively about an effective response to developments in technology.

Anyhow, it is perverse response to the development of technology to grant the government ever greater powers of repression in order to ensure that an archaic social institution can still be used to generate profits for a small group of powerful corporations and individuals.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Almost no one who wrote about the economy for a major news outlet was able to recognize the $8 trillion housing bubble that was driving the economy before it burst. Because people who write about the economy are not held responsible for the quality of their work, none of the people who missed this huge bubble were held accountable for this failure. Remarkably, many of them even now do not understand the bubble.

Robert Samuelson, the economic columnist for the Washington Post, is among this group. Today he writes that:

“some economists argue that China’s trade surpluses — converted into dollars and invested in U.S. bonds — fueled America’s financial crisis by driving down interest rates. Low rates then encouraged riskier mortgage loans.”

Actually, the problem was not low interest rates. Low interest rates are generally good for growth. The problem was that China’s trade surplus with the United States, along with the surplus of other countries, created a large gap in domestic demand. This gap in demand could only be filled by either government budget deficits or negative savings in the private sector. (This is a logical necessity – a trade deficit means negative national saving, there is no way around this story.)

Since folks who write for or get cited in the Washington Post were all yelling about budget deficits, there was no alternative to the housing bubble-type situation where ephemeral bubble wealth led to a consumption boom, while inflated house prices caused construction to surge.

Samuelson also concludes with a dire warning of a dollar crisis in which the value of the dollar plunges against other currencies. It is difficult to envision what this would look like. Right now, other countries are deliberately propping up the value of the dollar in order to preserve their export markets in the United States.

In order for this sort of crisis to come about, they would have to be prepared to give up not only their export markets but to also allow U.S. goods to become hyper-competitive in their home market. If the dollar were to fall to say, 3 yuan to a dollar (from close to 6 yuan to a dollar now) or 3 dollars to a euro, then U.S. exports would hugely undercut many domestically produced items in Europe, China and elsewhere. It is difficult to believe that these countries would allow this sort of disruption to their economies.

Almost no one who wrote about the economy for a major news outlet was able to recognize the $8 trillion housing bubble that was driving the economy before it burst. Because people who write about the economy are not held responsible for the quality of their work, none of the people who missed this huge bubble were held accountable for this failure. Remarkably, many of them even now do not understand the bubble.

Robert Samuelson, the economic columnist for the Washington Post, is among this group. Today he writes that:

“some economists argue that China’s trade surpluses — converted into dollars and invested in U.S. bonds — fueled America’s financial crisis by driving down interest rates. Low rates then encouraged riskier mortgage loans.”

Actually, the problem was not low interest rates. Low interest rates are generally good for growth. The problem was that China’s trade surplus with the United States, along with the surplus of other countries, created a large gap in domestic demand. This gap in demand could only be filled by either government budget deficits or negative savings in the private sector. (This is a logical necessity – a trade deficit means negative national saving, there is no way around this story.)

Since folks who write for or get cited in the Washington Post were all yelling about budget deficits, there was no alternative to the housing bubble-type situation where ephemeral bubble wealth led to a consumption boom, while inflated house prices caused construction to surge.

Samuelson also concludes with a dire warning of a dollar crisis in which the value of the dollar plunges against other currencies. It is difficult to envision what this would look like. Right now, other countries are deliberately propping up the value of the dollar in order to preserve their export markets in the United States.

In order for this sort of crisis to come about, they would have to be prepared to give up not only their export markets but to also allow U.S. goods to become hyper-competitive in their home market. If the dollar were to fall to say, 3 yuan to a dollar (from close to 6 yuan to a dollar now) or 3 dollars to a euro, then U.S. exports would hugely undercut many domestically produced items in Europe, China and elsewhere. It is difficult to believe that these countries would allow this sort of disruption to their economies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This column reports on the fact that people on the center and left of the political spectrum have a range of views in the debt/deficit, which the right seems fairly united in arguing for less government spending. It is worth noting that one reason why there may be divisions and confusions on this issue is that the media routinely allow politicians to say complete nonsense on this topic without correcting it.

For example, the piece tells readers:

“Mitt Romney takes up the same theme, with more subtlety, warning that Obama and the Democratic party are fostering a European-style welfare state with a growing ‘contingent of long-term jobless, dependent on government benefits for survival.'”

In fact, the generous European welfare states of northern Europe do not have a growing “contingent of long-term jobless, dependent on government benefits for survival.” Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Austria and Norway, the countries with the most generous welfare states, all have lower unemployment rates than the United States both short-term and long-term.

Competent reporters would ridicule Mr. Romney for making such an obviously false assertion, which suggests that either he has no idea of what he is talking about, or is deliberately misrepresenting reality to deceive voters. However, since this assertion generally goes unchallenged, Romney will continually repeat it, leading many in the public to believe that it is true.

This column reports on the fact that people on the center and left of the political spectrum have a range of views in the debt/deficit, which the right seems fairly united in arguing for less government spending. It is worth noting that one reason why there may be divisions and confusions on this issue is that the media routinely allow politicians to say complete nonsense on this topic without correcting it.

For example, the piece tells readers:

“Mitt Romney takes up the same theme, with more subtlety, warning that Obama and the Democratic party are fostering a European-style welfare state with a growing ‘contingent of long-term jobless, dependent on government benefits for survival.'”

In fact, the generous European welfare states of northern Europe do not have a growing “contingent of long-term jobless, dependent on government benefits for survival.” Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Austria and Norway, the countries with the most generous welfare states, all have lower unemployment rates than the United States both short-term and long-term.

Competent reporters would ridicule Mr. Romney for making such an obviously false assertion, which suggests that either he has no idea of what he is talking about, or is deliberately misrepresenting reality to deceive voters. However, since this assertion generally goes unchallenged, Romney will continually repeat it, leading many in the public to believe that it is true.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

An opinion column in the Post defending Europe against charges of being a continent of broken down socialist states, by Martin Klingst, the Washington bureau chief of the German newspaper Die Zeit, got the basic story of its economic crisis wrong. It told readers that Europe’s fiscal calamities, “stem in part from the unaffordable benefits for its citizens,” later adding, “it is also true that a number of E.U. countries have irresponsibly expanded their welfare systems and can no longer afford their bills.”

In fact, the 5 crisis countries (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain) all rank near the bottom in terms of the generosity of their welfare states. The European countries with the most generous welfare states, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, France and Germany, are mostly weathering the economic crisis relatively well.

The problems in the crisis countries stem in part from real estate bubbles that were allowed to grow unchecked by the European Central Bank (ECB), massive tax evasion (especially Greece and Italy), and the inflation fighting obsession of the ECB, coupled with its insistence that it would not act as a lender of last resort. The latter policy has caused the interest burden of these countries to soar. This has meant that a country like Spain faces a far higher interest rate than the U.K., which has a central bank that acts as a lender of last resort, even though the U.K. has a much higher debt burden.

An opinion column in the Post defending Europe against charges of being a continent of broken down socialist states, by Martin Klingst, the Washington bureau chief of the German newspaper Die Zeit, got the basic story of its economic crisis wrong. It told readers that Europe’s fiscal calamities, “stem in part from the unaffordable benefits for its citizens,” later adding, “it is also true that a number of E.U. countries have irresponsibly expanded their welfare systems and can no longer afford their bills.”

In fact, the 5 crisis countries (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain) all rank near the bottom in terms of the generosity of their welfare states. The European countries with the most generous welfare states, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, France and Germany, are mostly weathering the economic crisis relatively well.

The problems in the crisis countries stem in part from real estate bubbles that were allowed to grow unchecked by the European Central Bank (ECB), massive tax evasion (especially Greece and Italy), and the inflation fighting obsession of the ECB, coupled with its insistence that it would not act as a lender of last resort. The latter policy has caused the interest burden of these countries to soar. This has meant that a country like Spain faces a far higher interest rate than the U.K., which has a central bank that acts as a lender of last resort, even though the U.K. has a much higher debt burden.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post ran a piece on the growing number of foreigners who are going to work in Brazil, especially in its financial sector. It attributed this in part to Brazil’s rapid growth, which it reports as averaging 4.5 percent since 2004.

According to the IMF, Brazil’s growth has averaged 4.1 percent over this period. That is not especially fast for a developing country. Chile averaged an almost identical 4.0 percent over this period while Venezuela grew at a 4.5 percent rate and Argentina grew at a 7.3 percent rate.

If Brazil is attracting a large number of skilled workers from abroad it is primarily because of the lack of domestic supply, not rapid economic growth.

The Post ran a piece on the growing number of foreigners who are going to work in Brazil, especially in its financial sector. It attributed this in part to Brazil’s rapid growth, which it reports as averaging 4.5 percent since 2004.

According to the IMF, Brazil’s growth has averaged 4.1 percent over this period. That is not especially fast for a developing country. Chile averaged an almost identical 4.0 percent over this period while Venezuela grew at a 4.5 percent rate and Argentina grew at a 7.3 percent rate.

If Brazil is attracting a large number of skilled workers from abroad it is primarily because of the lack of domestic supply, not rapid economic growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It would have been worth including an explicit discussion of the trade deficit in the context of an assessment of employment prospects in manufacturing. At the moment, China and other developing countries are deliberately running large trade surpluses as a way to boost domestic demand. To do so, they are buying up huge amounts of dollars assets that essentially give them no real return. It is likely that at some point they will figure out how to generate demand domestically (e.g. hand out money to their citizens) and therefore will not have to pay people in the United States to buy their goods.

At that point we will either have to make our manufacturing goods ourselves or find a way to pay for the goods we import. The people who think that we will be able to pay for imported manufacturing goods with service exports have not examined the data. There is not a plausible story where increased U.S. exports of tourism (this is an export in national accounts), financial services or other components of the service sector will pay for our imports of manufactured goods.

It would have been worth including an explicit discussion of the trade deficit in the context of an assessment of employment prospects in manufacturing. At the moment, China and other developing countries are deliberately running large trade surpluses as a way to boost domestic demand. To do so, they are buying up huge amounts of dollars assets that essentially give them no real return. It is likely that at some point they will figure out how to generate demand domestically (e.g. hand out money to their citizens) and therefore will not have to pay people in the United States to buy their goods.

At that point we will either have to make our manufacturing goods ourselves or find a way to pay for the goods we import. The people who think that we will be able to pay for imported manufacturing goods with service exports have not examined the data. There is not a plausible story where increased U.S. exports of tourism (this is an export in national accounts), financial services or other components of the service sector will pay for our imports of manufactured goods.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A Washington Post editorial on indexing the minimum wage told readers:

“at the margins, minimum-wage increases probably destroy jobs in small restaurants, landscaping and janitorial firms.”

It then added:

“as the city of San Francisco, which has just imposed a highest-in-the-nation $10.24 minimum, may soon find out.”

Whether or not the first claim is accurate, the warning to San Francisco clearly is not. San Francisco first put its city-wide minimum wage in place in 2004. Since that time, it has risen in step with inflation. If the minimum wage was going to cost jobs the city should have seen the job loss already. Research on this issue failed to find any evidence of job loss — but the Post can still hope.

A Washington Post editorial on indexing the minimum wage told readers:

“at the margins, minimum-wage increases probably destroy jobs in small restaurants, landscaping and janitorial firms.”

It then added:

“as the city of San Francisco, which has just imposed a highest-in-the-nation $10.24 minimum, may soon find out.”

Whether or not the first claim is accurate, the warning to San Francisco clearly is not. San Francisco first put its city-wide minimum wage in place in 2004. Since that time, it has risen in step with inflation. If the minimum wage was going to cost jobs the city should have seen the job loss already. Research on this issue failed to find any evidence of job loss — but the Post can still hope.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión