An NYT Economix blognote overstated the effective decline in the labor share of national income over the last three decades by using gross national income rather than net national income. The note shares the labor compensation share declining by 4-5 percentage points over this period.

However, the depreciation share of gross domestic product rose by roughly 2 percentage points over this period. If we assume that this increase came proportionately from the capital and labor share of income, then the rise in the depreciation share would lead to a 1.2 percentage point reduction in the labor compensation share of gross national income.

Much of the loss of income by ordinary workers has been due to increased pay of CEOs, doctors, and other highly paid workers. This is still included as part of labor income.

An NYT Economix blognote overstated the effective decline in the labor share of national income over the last three decades by using gross national income rather than net national income. The note shares the labor compensation share declining by 4-5 percentage points over this period.

However, the depreciation share of gross domestic product rose by roughly 2 percentage points over this period. If we assume that this increase came proportionately from the capital and labor share of income, then the rise in the depreciation share would lead to a 1.2 percentage point reduction in the labor compensation share of gross national income.

Much of the loss of income by ordinary workers has been due to increased pay of CEOs, doctors, and other highly paid workers. This is still included as part of labor income.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post distinguished itself during the run-up of the housing bubble by relying on David Lereah, the chief economist with the National Association of Realtors, and author of Why the Real Estate Boom Will Not Bust and How You Can Profit from It, as its main source on the real estate market. It seems that it is continuing its policy of not using anyone knowledgeable about the housing market as a source for its articles on housing.

Its piece on President Obama’s new plan for mortgage refinancing implies that house prices will somehow rise back to their bubble levels. People who know about the housing market would tell readers that this would be like expecting the Nasdaq to bounce back to 5000 following its crash in 2000-2002. Unfortunately such voices continue to be excluded from the Post’s coverage of the housing market.

The Washington Post distinguished itself during the run-up of the housing bubble by relying on David Lereah, the chief economist with the National Association of Realtors, and author of Why the Real Estate Boom Will Not Bust and How You Can Profit from It, as its main source on the real estate market. It seems that it is continuing its policy of not using anyone knowledgeable about the housing market as a source for its articles on housing.

Its piece on President Obama’s new plan for mortgage refinancing implies that house prices will somehow rise back to their bubble levels. People who know about the housing market would tell readers that this would be like expecting the Nasdaq to bounce back to 5000 following its crash in 2000-2002. Unfortunately such voices continue to be excluded from the Post’s coverage of the housing market.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Morning Edition piece on President Obama’s new mortgage refinancing proposal implied that the housing market is a major drag on the economy. This is misleading.

The housing bubble was the motor of the economy during the last business cycle. It did this both by leading to a construction boom and by propelling consumption through the creation of $8 trillion of ephemeral equity. Now that the bubble has burst it can no longer play this role, however it is inaccurate to describe it as a drag on the economy.

Addendum:

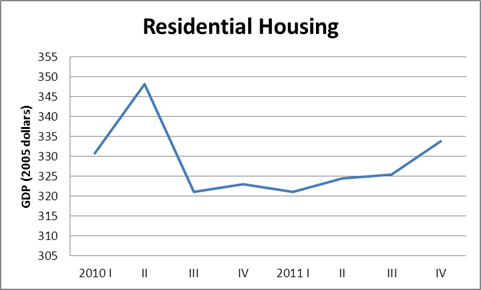

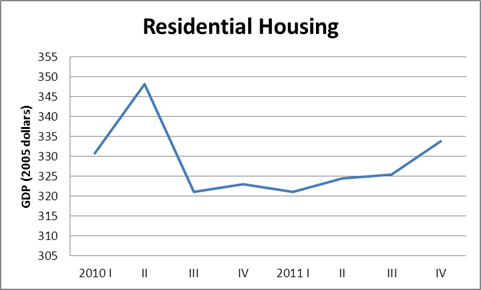

Since the comments suggest some confusion, let me be clear on what I mean by housing is not a drag on the recovery. The graph below shows real expenditures on residential construction over the last two years.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Note the direction that spending on residential construction (sorry, mislabeled the graph) has been going. That’s right, it has been going up! This is why some of us say that housing is not a drag on the recovery.

Now will housing be the force that leads out of the recovery? No, and it would be extremely foolish to expect otherwise, as I have written about endlessly. We got into this downturn because of the housing bubble. This led to a huge amount of overbuilding of housing. It will take years to wind this down to a more normal level.

This is exact opposite of a typical recovery which is led by housing. That is because a typical recession is caused by the Fed raising rates to slow the economy. That has the effect of slowing housing construction. When the Fed decides to take its foot off the break and lower interest rates to boost the economy, there is major pent up demand, which leads to a boom in housing. That is not the story here.

The wealth created by the housing bubble also led to a consumption boom. This is the long-known and widely forgotten housing wealth effect. This consumption boom is also not coming back for the simple reason that the housing bubble is not coming back.

Okay, so the collapse of the housing bubble caused the recession, which I probably have said more than any other person on the planet. But, at the moment housing is not a drag on the economy, it is adding to growth, even if it is not adding as much as we might like.

The Morning Edition piece on President Obama’s new mortgage refinancing proposal implied that the housing market is a major drag on the economy. This is misleading.

The housing bubble was the motor of the economy during the last business cycle. It did this both by leading to a construction boom and by propelling consumption through the creation of $8 trillion of ephemeral equity. Now that the bubble has burst it can no longer play this role, however it is inaccurate to describe it as a drag on the economy.

Addendum:

Since the comments suggest some confusion, let me be clear on what I mean by housing is not a drag on the recovery. The graph below shows real expenditures on residential construction over the last two years.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Note the direction that spending on residential construction (sorry, mislabeled the graph) has been going. That’s right, it has been going up! This is why some of us say that housing is not a drag on the recovery.

Now will housing be the force that leads out of the recovery? No, and it would be extremely foolish to expect otherwise, as I have written about endlessly. We got into this downturn because of the housing bubble. This led to a huge amount of overbuilding of housing. It will take years to wind this down to a more normal level.

This is exact opposite of a typical recovery which is led by housing. That is because a typical recession is caused by the Fed raising rates to slow the economy. That has the effect of slowing housing construction. When the Fed decides to take its foot off the break and lower interest rates to boost the economy, there is major pent up demand, which leads to a boom in housing. That is not the story here.

The wealth created by the housing bubble also led to a consumption boom. This is the long-known and widely forgotten housing wealth effect. This consumption boom is also not coming back for the simple reason that the housing bubble is not coming back.

Okay, so the collapse of the housing bubble caused the recession, which I probably have said more than any other person on the planet. But, at the moment housing is not a drag on the economy, it is adding to growth, even if it is not adding as much as we might like.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A Morning Edition segment on the recent European Union summit was headlined, “Most EU Nations to Sign Pact to Stop Overspending.” This is both flat-out wrong and misleading.

It is flat-out wrong because the pact restricts deficits, not spending. It is misleading because it implies that the current crisis was caused by overspending. It wasn’t. Most of the crisis countries had declining debt to GDP ratios before the downturn and two, Spain and Ireland, were actually running budget surpluses. The problem was caused by housing bubbles and the inept management of the economy by the European Central Bank.

A Morning Edition segment on the recent European Union summit was headlined, “Most EU Nations to Sign Pact to Stop Overspending.” This is both flat-out wrong and misleading.

It is flat-out wrong because the pact restricts deficits, not spending. It is misleading because it implies that the current crisis was caused by overspending. It wasn’t. Most of the crisis countries had declining debt to GDP ratios before the downturn and two, Spain and Ireland, were actually running budget surpluses. The problem was caused by housing bubbles and the inept management of the economy by the European Central Bank.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steven M. Davidoff had a Dealbook column complaining about a Dodd-Frank regulation that he argues is slowing the supply of capital to finance corporate takeovers. The issue in question is a requirement that the creator of a collaterized loan obligation (CLO) keep a 5 percent stake in the issue. Davidoff argues that many issuers of CLO’s are relatively small businesses and don’t have the capital to allow them to hold a 5 percent stake.

He then asks:

“So why add a new regulatory burden? It’s unclear what benefit a “skin in the game” rule would provide, given that C.L.O.’s are more akin to commercial loans, for which Dodd-Frank deems risk-retention rules unnecessary.”

The answer is that financial firms can make money by misrepresenting the products they sell. Those who are good at misrepresentation can get very rich. While some misrepresentations may be in violation of the law, it is often difficult to prove that misrepresentations were made to sell a product. This makes even civil litigation difficult, criminal prosecution is rare.

Forcing the creators of CLO’s to keep a stake is a way to help ensure that they consider the asset they have created to be good. In principle, the sophisticated institutional investors who buy stakes in CLO’s should be able to assess their quality themselves, however one lesson from the housing bubble is that they seem to lack this ability.

Steven M. Davidoff had a Dealbook column complaining about a Dodd-Frank regulation that he argues is slowing the supply of capital to finance corporate takeovers. The issue in question is a requirement that the creator of a collaterized loan obligation (CLO) keep a 5 percent stake in the issue. Davidoff argues that many issuers of CLO’s are relatively small businesses and don’t have the capital to allow them to hold a 5 percent stake.

He then asks:

“So why add a new regulatory burden? It’s unclear what benefit a “skin in the game” rule would provide, given that C.L.O.’s are more akin to commercial loans, for which Dodd-Frank deems risk-retention rules unnecessary.”

The answer is that financial firms can make money by misrepresenting the products they sell. Those who are good at misrepresentation can get very rich. While some misrepresentations may be in violation of the law, it is often difficult to prove that misrepresentations were made to sell a product. This makes even civil litigation difficult, criminal prosecution is rare.

Forcing the creators of CLO’s to keep a stake is a way to help ensure that they consider the asset they have created to be good. In principle, the sophisticated institutional investors who buy stakes in CLO’s should be able to assess their quality themselves, however one lesson from the housing bubble is that they seem to lack this ability.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

People who report on Germany’s economy should know that the unemployment rate reported by the government is not calculated the same way as the U.S. unemployment rate. It includes people who are working part-time but would like full-time jobs as being unemployed. This means that the rate reported by the government is not directly comparable to the U.S. rate. This means that the NYT misled readers when it told them that Germany’s unemployment rate fell to 6.7 percent in January.

However, the OECD does publish unemployment rates for Germany that are calculated in a similar manner to the U.S. unemployment rate. By this measure, Germany’s unemployment rate was 5.5 percent in November. Assuming that the OECD rate followed the same path as the German government rate, German’s unemployment rate would be 5.3-5.4 percent today if calculated on a comparable basis to the U.S. rate.

People who report on Germany’s economy should know that the unemployment rate reported by the government is not calculated the same way as the U.S. unemployment rate. It includes people who are working part-time but would like full-time jobs as being unemployed. This means that the rate reported by the government is not directly comparable to the U.S. rate. This means that the NYT misled readers when it told them that Germany’s unemployment rate fell to 6.7 percent in January.

However, the OECD does publish unemployment rates for Germany that are calculated in a similar manner to the U.S. unemployment rate. By this measure, Germany’s unemployment rate was 5.5 percent in November. Assuming that the OECD rate followed the same path as the German government rate, German’s unemployment rate would be 5.3-5.4 percent today if calculated on a comparable basis to the U.S. rate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

By Mark Weisbrot

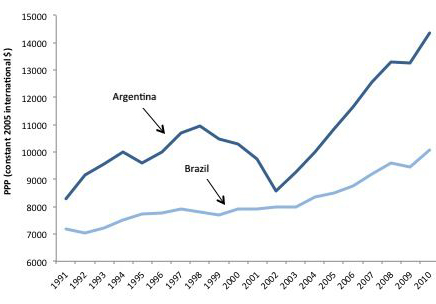

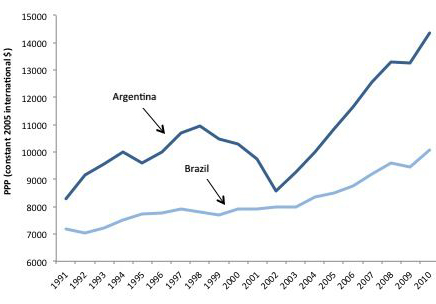

An article in Saturday’s New York Timesclaimed that Brazil had “tripled its per capita income over the past decade.” In fact, Brazil’s real per capita income (per capita GDP) has grown by about 30 percent from 2001-2011.

The article notes that “some of that increase has to do with its [Brazil’s ] overvalued currency”, but (1) even this cannot account for the vast difference between 200 percent and 30 percent, and (2) even if it all of this “growth” were due to currency appreciation, the measure used would still be wrong. Brazilians earn and spend about 90 percent of their income in domestic currency; the correct measure of their income growth is therefore in their own currency, adjusted for inflation. That has grown about 30 percent per capita over the decade.

Brazil would look like quite a different country today if it had really tripled its per capita income over the past ten years.

The article also presents a somewhat misleading impression of Brazil as compared with Argentina, which is common in the media, where Brazil “now flexes its economic muscle,” and “Argentina is the dean of the club of nations utterly obsessed with their decline” (an Argentine scholar quoted in the article). Although the article notes that Argentina had a “robust recovery after defaulting on its debts,” the reader is left with the impression that Brazil has been an economic success story as compared with Argentina.

The chart below shows real per capita income in Argentina compared with Brazil (on a purchasing power parity basis). It can be seen that, even though Brazil has greatly increased its growth rate since 2004, Argentina has pulled ahead so rapidly since in recent years that the gap has widened enormously. Income per person is now about 40 percent higher in Argentina than in Brazil. Since income is much more unequally distributed in Brazil than Argentina, this income gap means an even wider gap for the poor and the majority of the population.

Per Capita Income: Argentina and Brazil

Source: World Bank.

By Mark Weisbrot

An article in Saturday’s New York Timesclaimed that Brazil had “tripled its per capita income over the past decade.” In fact, Brazil’s real per capita income (per capita GDP) has grown by about 30 percent from 2001-2011.

The article notes that “some of that increase has to do with its [Brazil’s ] overvalued currency”, but (1) even this cannot account for the vast difference between 200 percent and 30 percent, and (2) even if it all of this “growth” were due to currency appreciation, the measure used would still be wrong. Brazilians earn and spend about 90 percent of their income in domestic currency; the correct measure of their income growth is therefore in their own currency, adjusted for inflation. That has grown about 30 percent per capita over the decade.

Brazil would look like quite a different country today if it had really tripled its per capita income over the past ten years.

The article also presents a somewhat misleading impression of Brazil as compared with Argentina, which is common in the media, where Brazil “now flexes its economic muscle,” and “Argentina is the dean of the club of nations utterly obsessed with their decline” (an Argentine scholar quoted in the article). Although the article notes that Argentina had a “robust recovery after defaulting on its debts,” the reader is left with the impression that Brazil has been an economic success story as compared with Argentina.

The chart below shows real per capita income in Argentina compared with Brazil (on a purchasing power parity basis). It can be seen that, even though Brazil has greatly increased its growth rate since 2004, Argentina has pulled ahead so rapidly since in recent years that the gap has widened enormously. Income per person is now about 40 percent higher in Argentina than in Brazil. Since income is much more unequally distributed in Brazil than Argentina, this income gap means an even wider gap for the poor and the majority of the population.

Per Capita Income: Argentina and Brazil

Source: World Bank.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Japan is a densely populated country. As a result, housing is extremely expensive in its major cities. Its subway system is so crowded that Tokyo has people who push people into the subway cars to ensure that no space is wasted.

Given this situation, it was striking to see that the Independent report on Japan’s “demographic crisis” and ABC News tell us about Japan’s “dire picture.” Their concern is that Japan’s population is projected to shrink by about a third over the next 50 years.

While these news outlets might be terrified by the prospect that the Japanese will pay less for housing, it is not clear why the Japanese should have such concerns. The implication is that the increase in the ratio of retirees to workers will impose a devastating burden on the working population.

Those who know arithmetic don’t share such concerns. Productivity growth in Japan has averaged almost 2.0 percent annually over the last two decades. At this rate, output per worker hour will be nearly 170 percent higher in 50 years.

This means that if retirees consume 80 percent as much as active workers, and the ratio of workers to retirees fall from 2.5 today to 1.8 in 50 years, then consumption per worker and per retiree can increase by 120 percent over this period, assuming no reduction in hours worked.

In fact, this would understate the actual gain in living standards since there will be fewer children to support and there will also be gains in living standards associated with less crowding. (Tokyo won’t need to pay workers to push people into subway cars.)

In short, worrying about demographics might be a good way to create jobs in the current economic environment, it need not be a concern for serious people.

[Thanks to Keane Bhatt and Victor Silberman.]

Japan is a densely populated country. As a result, housing is extremely expensive in its major cities. Its subway system is so crowded that Tokyo has people who push people into the subway cars to ensure that no space is wasted.

Given this situation, it was striking to see that the Independent report on Japan’s “demographic crisis” and ABC News tell us about Japan’s “dire picture.” Their concern is that Japan’s population is projected to shrink by about a third over the next 50 years.

While these news outlets might be terrified by the prospect that the Japanese will pay less for housing, it is not clear why the Japanese should have such concerns. The implication is that the increase in the ratio of retirees to workers will impose a devastating burden on the working population.

Those who know arithmetic don’t share such concerns. Productivity growth in Japan has averaged almost 2.0 percent annually over the last two decades. At this rate, output per worker hour will be nearly 170 percent higher in 50 years.

This means that if retirees consume 80 percent as much as active workers, and the ratio of workers to retirees fall from 2.5 today to 1.8 in 50 years, then consumption per worker and per retiree can increase by 120 percent over this period, assuming no reduction in hours worked.

In fact, this would understate the actual gain in living standards since there will be fewer children to support and there will also be gains in living standards associated with less crowding. (Tokyo won’t need to pay workers to push people into subway cars.)

In short, worrying about demographics might be a good way to create jobs in the current economic environment, it need not be a concern for serious people.

[Thanks to Keane Bhatt and Victor Silberman.]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Even though the data on income show the top 1 percent of the population pulling away from everyone else, New York Times columnist David Brooks tells us that focusing on the 1 percent is a “distraction.” He bases this assertion on, well absolutely nothing.

Brooks goes to tell readers that:

“the truth is, members of the upper tribe have made themselves phenomenally productive.”

This is striking for two reasons. Since his upper tribe is the whole top 20 percent, much of this group that has become phenomenally productive has seen little benefit from their productivity. Wages for the second decile have risen over the last three decades, but not by very much.

The other part of the story is that this group has made itself phenomenally productive largely through its control of the political process. For example, it has used the political process to get an implicit government guarantee for too big to fail banks that can pay its top executives phenomenal amounts of money. It maintains protectionist barriers for doctors, lawyers and other highly educated professionals that allow their pay to soar relative to workers who must compete in the international economy. And it has garnered ever stronger patent protection that has shifted income from ordinary workers to those able to earn patent rents.

It was control over the political process that has allowed the 1 percent to profit at everyone else’s expense. Their productivity, whether phenomenal or not, was secondary.

Even though the data on income show the top 1 percent of the population pulling away from everyone else, New York Times columnist David Brooks tells us that focusing on the 1 percent is a “distraction.” He bases this assertion on, well absolutely nothing.

Brooks goes to tell readers that:

“the truth is, members of the upper tribe have made themselves phenomenally productive.”

This is striking for two reasons. Since his upper tribe is the whole top 20 percent, much of this group that has become phenomenally productive has seen little benefit from their productivity. Wages for the second decile have risen over the last three decades, but not by very much.

The other part of the story is that this group has made itself phenomenally productive largely through its control of the political process. For example, it has used the political process to get an implicit government guarantee for too big to fail banks that can pay its top executives phenomenal amounts of money. It maintains protectionist barriers for doctors, lawyers and other highly educated professionals that allow their pay to soar relative to workers who must compete in the international economy. And it has garnered ever stronger patent protection that has shifted income from ordinary workers to those able to earn patent rents.

It was control over the political process that has allowed the 1 percent to profit at everyone else’s expense. Their productivity, whether phenomenal or not, was secondary.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In a major business section article on President Obama’s plans to address inequality, the Washington Post (a.k.a. Fox on 15th Street) came down squarely on the side of the Republicans. The Republican slant starts with the headline, “Obama’s push to revive middle class will clash with long-term trends.” This one undoubtedly had people all over the metro area saying, “duh.”

Of course it will clash with long-term trends, that would be the point. No one thinks that the 1 percent just got all of our money yesterday. The process of upward redistribution has been going on for more than three decades.

After outlining the basic issues, the Post tells readers:

“Republicans, both in Congress and on the campaign trail, favor a far different approach than Obama has embraced. They generally regard government efforts to promote equality and strengthen the middle class as counterproductive. By this thinking, reducing taxes and shrinking the government’s role in the economy will free up capital that entrepreneurs can invest, creating good new jobs.”

Actually, the Post has no idea how Republicans “regard” government efforts to promote equality. Nor does it know whether in their “thinking” lower taxes for the wealthy actually translates into “good new jobs.”

What the Post knows is what Republican politicians and spokespeople say. A serious newspaper sticks to what is visible and knowable, it does not do mind reading for the benefit of its readers.

The piece also includes a number of assertions that are unsupported by anything. For example, it tells readers:

“But it is not clear that the measures [those proposed by President Obama]— or any others — could compensate for the factors behind the decline of the middle class, including the rise of nations with abundant cheap labor and the development of new technologies that allow companies to operate with far fewer workers.”

Actually, the abundant supply of cheap labor could do much to make middle class workers wealthier if it were allowed to compete freely with the most highly educated workers in the United States. There is no shortage of smart people in China, India, and other developing countries who could train to be doctors in the United States. If we eliminated the barriers that make it difficult for foreign doctors who meet U.S. standards from practicing in the United States, it would would substantially reduce the pay of physicians.

If the salaries of doctors fell to European levels it would mean a dividend for the middle class (in the form of lower health care bills) of close to $100 billion a year, almost twice the amount at stake in extending President Bush’s tax cuts to the wealthy. There would be comparable gains from opening up law and other high-paying professions to people from the developing world.

The reason that globalization has put downward pressure on the living standards of the middle class is that it has been deliberate policy under both Republican and Democratic administrations to force middle class workers to compete with their low-paid counterparts in the developing world, while protecting the most highly educated workers from the same competition. The predicted and actual result of this policy has been an enormous upward redistribution of income.

A serious piece on inequality would have made this point. It also would have discussed other ways in which conscious policy decisions (e.g. greater legal hostility to unions) have resulted in upward redistribution, instead of telling readers it was all just the natural workings of the economy.

In a major business section article on President Obama’s plans to address inequality, the Washington Post (a.k.a. Fox on 15th Street) came down squarely on the side of the Republicans. The Republican slant starts with the headline, “Obama’s push to revive middle class will clash with long-term trends.” This one undoubtedly had people all over the metro area saying, “duh.”

Of course it will clash with long-term trends, that would be the point. No one thinks that the 1 percent just got all of our money yesterday. The process of upward redistribution has been going on for more than three decades.

After outlining the basic issues, the Post tells readers:

“Republicans, both in Congress and on the campaign trail, favor a far different approach than Obama has embraced. They generally regard government efforts to promote equality and strengthen the middle class as counterproductive. By this thinking, reducing taxes and shrinking the government’s role in the economy will free up capital that entrepreneurs can invest, creating good new jobs.”

Actually, the Post has no idea how Republicans “regard” government efforts to promote equality. Nor does it know whether in their “thinking” lower taxes for the wealthy actually translates into “good new jobs.”

What the Post knows is what Republican politicians and spokespeople say. A serious newspaper sticks to what is visible and knowable, it does not do mind reading for the benefit of its readers.

The piece also includes a number of assertions that are unsupported by anything. For example, it tells readers:

“But it is not clear that the measures [those proposed by President Obama]— or any others — could compensate for the factors behind the decline of the middle class, including the rise of nations with abundant cheap labor and the development of new technologies that allow companies to operate with far fewer workers.”

Actually, the abundant supply of cheap labor could do much to make middle class workers wealthier if it were allowed to compete freely with the most highly educated workers in the United States. There is no shortage of smart people in China, India, and other developing countries who could train to be doctors in the United States. If we eliminated the barriers that make it difficult for foreign doctors who meet U.S. standards from practicing in the United States, it would would substantially reduce the pay of physicians.

If the salaries of doctors fell to European levels it would mean a dividend for the middle class (in the form of lower health care bills) of close to $100 billion a year, almost twice the amount at stake in extending President Bush’s tax cuts to the wealthy. There would be comparable gains from opening up law and other high-paying professions to people from the developing world.

The reason that globalization has put downward pressure on the living standards of the middle class is that it has been deliberate policy under both Republican and Democratic administrations to force middle class workers to compete with their low-paid counterparts in the developing world, while protecting the most highly educated workers from the same competition. The predicted and actual result of this policy has been an enormous upward redistribution of income.

A serious piece on inequality would have made this point. It also would have discussed other ways in which conscious policy decisions (e.g. greater legal hostility to unions) have resulted in upward redistribution, instead of telling readers it was all just the natural workings of the economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión