At this point it should be universally known that the Federal Reserve Board has been guilty of disastrous incompetence. It allowed an $8 trillion housing bubble to grow unchecked. The inevitable collapse of this bubble has produced the worst downturn since the Great Depression and ruined the lives of tens of millions of people across the country.

This is why it was striking to read a Washington Post headline for an article on newly released Fed transcripts that showed that Greenspan and the rest of the Fed were completely oblivious to the bubble and the risks it posed to the economy as late as 2006:

“Fed’s image tarnished by newly released transcripts.”

At this point, the Fed should not have an image that could possibly be tarnished further. If its record had been reported accurately, everyone would be well aware of its incredible incompetence as a manager of the economy.

btw, as noted in the article, many of the people at these Fed meetings are still in top policy making positions. This shows that the U.S. economy still produces good-paying jobs for people without skills.

Addendum: This is what people who were not Greenspan sycophants were saying at the time. And, here’s another blast from the past.

At this point it should be universally known that the Federal Reserve Board has been guilty of disastrous incompetence. It allowed an $8 trillion housing bubble to grow unchecked. The inevitable collapse of this bubble has produced the worst downturn since the Great Depression and ruined the lives of tens of millions of people across the country.

This is why it was striking to read a Washington Post headline for an article on newly released Fed transcripts that showed that Greenspan and the rest of the Fed were completely oblivious to the bubble and the risks it posed to the economy as late as 2006:

“Fed’s image tarnished by newly released transcripts.”

At this point, the Fed should not have an image that could possibly be tarnished further. If its record had been reported accurately, everyone would be well aware of its incredible incompetence as a manager of the economy.

btw, as noted in the article, many of the people at these Fed meetings are still in top policy making positions. This shows that the U.S. economy still produces good-paying jobs for people without skills.

Addendum: This is what people who were not Greenspan sycophants were saying at the time. And, here’s another blast from the past.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A Morning Edition segment today told listeners (sorry, no link yet) that “there’s no doubt that private equity firms create value,” which it then justified by referring to the high returns earned by those who invest in private equity (PE) companies. This is WRONG!!!!!!!!!!!!

First, it is not at all clear that those who invest in PE funds (not the PE partners themselves) do beat the stock market when a full accounting is done. Recent research shows that net of fees, private equity investors (pension funds and university endowments) would have been better off buying the S&P 500.

Furthermore, even if the PE investors did come out ahead, this does not mean it created value. Investors in Bernie Madoff’s fund, who got out, made money too, but Bernie Madoff did not create value.

Much of what private equity does is financial engineering. For example, it is standard to load up the companies they purchase with debt. The resulting interest payments are tax deductible. This increases profitability but creates no value for the economy. It simply transfers money from taxpayers to the private equity company.

To take a simple example, suppose a public company (let’s call it Gingrich Inc.), has $1 billion a year in profits. If Gingrich Inc. paid taxes at the full 35 percent rate (fat chance), it would have $650 million [thanks Robert] a year to either keep as retained earnings or to pay out as dividends to its shareholders.

Now suppose that a PE company (we’ll call it Romney Capital) steps in. The current price to earnings ratio in the stock market is around 14, so Gingrich Inc. would have a pre-takeover market value of approximately $9.2 billion (14*$650 million). Romney Capital then arranges for Gingrich Inc. to borrow $6 billion which it pays out as a dividend to itself. This means that the Romney Capital has just gotten back almost two-thirds of its investment.

Suppose that Gingrich Inc. pays 5 percent interest on its debt (closer to the 5.20 Baa rate than the 3.80 Aaa rate). This means that before tax profit falls by $300 million. This leaves Gingrich Inc. with $700 million in before tax profit. Deducting the 35 percent tax, Gingrich Inc. now has $455 million a year to distribute to Romney Capital, 70 percent as much as before ($455 million/$700 million) even though Romney Capital has already recovered two-thirds of what it paid for Gingrich Inc.. In this case, the benefit to the Romney Capital came at the expense of taxpayers, not through the creation of value.

Now suppose that the Romney Capital arranges to sell off some of Gingrich Inc.’s assets, such as real estate or a highly profitable subsidiary, and then uses the proceeds to make a payment to the Romney Capital rather than leaving the money under the control of Gingrich Inc. Such sales may allow Romney Capital to recoup the rest of its investment and possibly more. Gingrich Inc. is then left as a highly indebted company with few assets.

In this story, Romney Capital may have earned a substantial profit on a limited investment (it recouped most of its money almost immediately when it loaded Gingrich Inc. with debt), without doing anything to improve the operation of Gingrich Inc. If Gingrich Inc. manages to stay in business and generate profits, then this will increase the return. Romney Capital may be able to resell the company and treat the whole sale price as profit.

On the other hand, if Gingrich Inc. goes bankrupt, this will primarily be a problem for creditors, since Romney Capital has already gotten its investment back. In effect, Romney Capital might have secured large gains entirely by financial engineering, while creating no value whatsoever.

The sort of asset stripping described here, which harms creditors by taking away potential collateral for their loans, violates the law. However it is extremely difficult to prevent, especially with private equity companies that have to make few public disclosures. If Gingrich Inc. were to fall into bankruptcy, this is the sort of thing that would likely be contested in the bankruptcy proceedings. Of course the resources used in fighting out this sort of legal battle are a pure waste from an economic perspective.

Anyhow, these are the sorts of issues that are raised with private equity. It is flat out untrue to say, as NPR does:

“Here’s what private equity firms like Bain Capital do: First, they go out and find a few large investors — usually pension funds, university endowments and possibly wealthy individuals. Then, says Ohio State professor Steven Davidoff, they take that money, borrow a lot more, and buy companies — usually companies that are in trouble or undervalued.

‘They buy them in hopes that they can increase the value of the companies and sell them at a fantastic profit,’ Davidoff says.”

Private equity companies absolutely do not have to increase the value of a company to make a profit. They can end up making a profit on their investment even if they take the company into bankruptcy and leave it much worse off than it was before the takeover.

A Morning Edition segment today told listeners (sorry, no link yet) that “there’s no doubt that private equity firms create value,” which it then justified by referring to the high returns earned by those who invest in private equity (PE) companies. This is WRONG!!!!!!!!!!!!

First, it is not at all clear that those who invest in PE funds (not the PE partners themselves) do beat the stock market when a full accounting is done. Recent research shows that net of fees, private equity investors (pension funds and university endowments) would have been better off buying the S&P 500.

Furthermore, even if the PE investors did come out ahead, this does not mean it created value. Investors in Bernie Madoff’s fund, who got out, made money too, but Bernie Madoff did not create value.

Much of what private equity does is financial engineering. For example, it is standard to load up the companies they purchase with debt. The resulting interest payments are tax deductible. This increases profitability but creates no value for the economy. It simply transfers money from taxpayers to the private equity company.

To take a simple example, suppose a public company (let’s call it Gingrich Inc.), has $1 billion a year in profits. If Gingrich Inc. paid taxes at the full 35 percent rate (fat chance), it would have $650 million [thanks Robert] a year to either keep as retained earnings or to pay out as dividends to its shareholders.

Now suppose that a PE company (we’ll call it Romney Capital) steps in. The current price to earnings ratio in the stock market is around 14, so Gingrich Inc. would have a pre-takeover market value of approximately $9.2 billion (14*$650 million). Romney Capital then arranges for Gingrich Inc. to borrow $6 billion which it pays out as a dividend to itself. This means that the Romney Capital has just gotten back almost two-thirds of its investment.

Suppose that Gingrich Inc. pays 5 percent interest on its debt (closer to the 5.20 Baa rate than the 3.80 Aaa rate). This means that before tax profit falls by $300 million. This leaves Gingrich Inc. with $700 million in before tax profit. Deducting the 35 percent tax, Gingrich Inc. now has $455 million a year to distribute to Romney Capital, 70 percent as much as before ($455 million/$700 million) even though Romney Capital has already recovered two-thirds of what it paid for Gingrich Inc.. In this case, the benefit to the Romney Capital came at the expense of taxpayers, not through the creation of value.

Now suppose that the Romney Capital arranges to sell off some of Gingrich Inc.’s assets, such as real estate or a highly profitable subsidiary, and then uses the proceeds to make a payment to the Romney Capital rather than leaving the money under the control of Gingrich Inc. Such sales may allow Romney Capital to recoup the rest of its investment and possibly more. Gingrich Inc. is then left as a highly indebted company with few assets.

In this story, Romney Capital may have earned a substantial profit on a limited investment (it recouped most of its money almost immediately when it loaded Gingrich Inc. with debt), without doing anything to improve the operation of Gingrich Inc. If Gingrich Inc. manages to stay in business and generate profits, then this will increase the return. Romney Capital may be able to resell the company and treat the whole sale price as profit.

On the other hand, if Gingrich Inc. goes bankrupt, this will primarily be a problem for creditors, since Romney Capital has already gotten its investment back. In effect, Romney Capital might have secured large gains entirely by financial engineering, while creating no value whatsoever.

The sort of asset stripping described here, which harms creditors by taking away potential collateral for their loans, violates the law. However it is extremely difficult to prevent, especially with private equity companies that have to make few public disclosures. If Gingrich Inc. were to fall into bankruptcy, this is the sort of thing that would likely be contested in the bankruptcy proceedings. Of course the resources used in fighting out this sort of legal battle are a pure waste from an economic perspective.

Anyhow, these are the sorts of issues that are raised with private equity. It is flat out untrue to say, as NPR does:

“Here’s what private equity firms like Bain Capital do: First, they go out and find a few large investors — usually pension funds, university endowments and possibly wealthy individuals. Then, says Ohio State professor Steven Davidoff, they take that money, borrow a lot more, and buy companies — usually companies that are in trouble or undervalued.

‘They buy them in hopes that they can increase the value of the companies and sell them at a fantastic profit,’ Davidoff says.”

Private equity companies absolutely do not have to increase the value of a company to make a profit. They can end up making a profit on their investment even if they take the company into bankruptcy and leave it much worse off than it was before the takeover.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In an article explaining why older people are increasingly deciding to work the Washington Post neglected to mention the cost of health care. If a person over 55 is not getting health care insurance through their employer, the cost of insurance would typically be more than $10,000 per year per person and several times this amount for people with a pre-existing condition. The rising cost of care and the sharp decline in the percentage of workers with retiree health benefits is undoubtedly a major factor behind the decision of more older workers to remain in the workforce.

In an article explaining why older people are increasingly deciding to work the Washington Post neglected to mention the cost of health care. If a person over 55 is not getting health care insurance through their employer, the cost of insurance would typically be more than $10,000 per year per person and several times this amount for people with a pre-existing condition. The rising cost of care and the sharp decline in the percentage of workers with retiree health benefits is undoubtedly a major factor behind the decision of more older workers to remain in the workforce.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It looks like unemployment is on the rise again, new claims for unemployment insurance jumped to 399,000 last week. That is 24,000 more than the consensus forecast and also 24,000 more than the prior week’s number. So let’s see some of those shrill talking heads getting scared — real bad news for President Obama’s re-election prospects.

Of course folks who know some economics remember that the December data showed a peculiar jump of 42,000 jobs in the courier industry in December. The same thing happened last year. Last year, all those jobs disappeared in January. And last year there was a jump in claims of 19,000 for the second week in January. Let’s see if we can guess what this all means.

It looks like unemployment is on the rise again, new claims for unemployment insurance jumped to 399,000 last week. That is 24,000 more than the consensus forecast and also 24,000 more than the prior week’s number. So let’s see some of those shrill talking heads getting scared — real bad news for President Obama’s re-election prospects.

Of course folks who know some economics remember that the December data showed a peculiar jump of 42,000 jobs in the courier industry in December. The same thing happened last year. Last year, all those jobs disappeared in January. And last year there was a jump in claims of 19,000 for the second week in January. Let’s see if we can guess what this all means.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

One of the simplest ways in which the media could improve their reporting is by reporting numbers in ways that make sense to their readers. When the Washington Post told readers that Germany’s economy shrank by 0.25 percent in the 4th quarter, I would suspect that more 99 percent of readers thought this was an annual rate of decline, which is way numbers are always reported for the United States.

In fact, this is a quarterly rate of decline, which is the standard practice in Europe and much of the rest of the world. It is not hard to convert quarterly growth numbers to an annual rate. For small numbers, multiplying by four will do the trick. (For larger numbers it is necessary to take the growth figure to the 4th power, but that still is not hard.)

One of the simplest ways in which the media could improve their reporting is by reporting numbers in ways that make sense to their readers. When the Washington Post told readers that Germany’s economy shrank by 0.25 percent in the 4th quarter, I would suspect that more 99 percent of readers thought this was an annual rate of decline, which is way numbers are always reported for the United States.

In fact, this is a quarterly rate of decline, which is the standard practice in Europe and much of the rest of the world. It is not hard to convert quarterly growth numbers to an annual rate. For small numbers, multiplying by four will do the trick. (For larger numbers it is necessary to take the growth figure to the 4th power, but that still is not hard.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This point would have been worth making in an NYT article on Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner’s trip to China. The article notes that Geithner will likely try to prod China to raise the value of its currency against the dollar. It also reports that:

“American corporations in industries like telecommunications and financial services have increasingly complained that China continues to restrict their access to domestic markets, despite pledges of openness when China joined the World Trade Organization a decade ago.”

Insofar as Geithner makes a priority of pushing for increased market access for the financial and telecommunications industry it will almost certainly mean less progress on raising the value of the yuan against the dollar. The United States is not in a position to simply dictate conditions to China, so getting more concessions in one area almost certainly means getting fewer concessions in other areas.

This means that if Geithner succeeds in getting concessions from China on market access for financial and telecommunications firms, it will likely be at the expense of achieving more progress on lowering the dollar against the yuan. This would mean in effect that he will have placed the interest of these industries ahead of the interest of U.S. manufacturing workers, since we could potentially gain millions of manufacturing jobs from a lower valued dollar.

This trade-off should have been made clearer in the article.

This point would have been worth making in an NYT article on Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner’s trip to China. The article notes that Geithner will likely try to prod China to raise the value of its currency against the dollar. It also reports that:

“American corporations in industries like telecommunications and financial services have increasingly complained that China continues to restrict their access to domestic markets, despite pledges of openness when China joined the World Trade Organization a decade ago.”

Insofar as Geithner makes a priority of pushing for increased market access for the financial and telecommunications industry it will almost certainly mean less progress on raising the value of the yuan against the dollar. The United States is not in a position to simply dictate conditions to China, so getting more concessions in one area almost certainly means getting fewer concessions in other areas.

This means that if Geithner succeeds in getting concessions from China on market access for financial and telecommunications firms, it will likely be at the expense of achieving more progress on lowering the dollar against the yuan. This would mean in effect that he will have placed the interest of these industries ahead of the interest of U.S. manufacturing workers, since we could potentially gain millions of manufacturing jobs from a lower valued dollar.

This trade-off should have been made clearer in the article.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article discussing whether private equity firms are good or bad for the economy. The piece failed to focus on the real issues.

The focus of the piece is whether private equity increases or decreases the number of jobs in the firms it controls. This is not really a good measure of whether the industry is good or bad for the economy.

If private equity firms were successful in making companies more efficient and lowering prices to consumers, then it could lead to more jobs in the economy, even if there were fewer workers directly employed in the firms under its control. (This does not really apply in the current economy, where inefficiency means more workers are employed. This is good in the context of a poorly managed macroeconomy with high unemployment.)

However private equity firms do not profit just by making firms more efficient. Private equity also profits by financial engineering. For example, it is standard practice for private equity firms to load their firms with debt. This means that interest payments, which are tax deductible, are substituted for dividend payments, which are not tax deductible.

Private equity companies also often force firms into bankruptcy to offload debt. This can often include pension obligations, which are then taken over by the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation. Insofar as private equity companies are drawing their profit from this sort of financial engineering, it is not providing a benefit to the economy. In fact, it is a direct drain on the productive economy.

Clearly private equity companies engage in both practices (increasing efficiency and financial engineering). There is no definitive study showing which is more important to its profits and whether the efficiency gains exceeds the waste associated with financial engineering.

At one point the article quotes R. Glenn Hubbard, the dean of the Columbia Business School and one of Mr. Romney’s economic advisers (who also played a starring role in the movie Inside Job), saying:

“private equity firms have an impact on productivity … That doesn’t mean that people don’t lose their jobs. But the question of whether private equity adds value? It’s settled among economists.”

It would have been helpful to include the view of a less partisan economist who could have told readers that this is not true.

The NYT had an article discussing whether private equity firms are good or bad for the economy. The piece failed to focus on the real issues.

The focus of the piece is whether private equity increases or decreases the number of jobs in the firms it controls. This is not really a good measure of whether the industry is good or bad for the economy.

If private equity firms were successful in making companies more efficient and lowering prices to consumers, then it could lead to more jobs in the economy, even if there were fewer workers directly employed in the firms under its control. (This does not really apply in the current economy, where inefficiency means more workers are employed. This is good in the context of a poorly managed macroeconomy with high unemployment.)

However private equity firms do not profit just by making firms more efficient. Private equity also profits by financial engineering. For example, it is standard practice for private equity firms to load their firms with debt. This means that interest payments, which are tax deductible, are substituted for dividend payments, which are not tax deductible.

Private equity companies also often force firms into bankruptcy to offload debt. This can often include pension obligations, which are then taken over by the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation. Insofar as private equity companies are drawing their profit from this sort of financial engineering, it is not providing a benefit to the economy. In fact, it is a direct drain on the productive economy.

Clearly private equity companies engage in both practices (increasing efficiency and financial engineering). There is no definitive study showing which is more important to its profits and whether the efficiency gains exceeds the waste associated with financial engineering.

At one point the article quotes R. Glenn Hubbard, the dean of the Columbia Business School and one of Mr. Romney’s economic advisers (who also played a starring role in the movie Inside Job), saying:

“private equity firms have an impact on productivity … That doesn’t mean that people don’t lose their jobs. But the question of whether private equity adds value? It’s settled among economists.”

It would have been helpful to include the view of a less partisan economist who could have told readers that this is not true.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

No one reads Washington Post editorials for their astute economic analysis. The paper did not surprise readers with its balanced discussion of private equity today.

While the paper is right to point out that whether private equity firms directly increase or decrease employment is not a good measure of whether they are beneficial to the economy, it totally overlooked the main issues surrounding private equity and its impact on the economy. The question is whether the high profits earned by the partners are primarily due to increasing economic efficiency or to rents earned by dumping costs on others.

As noted here, it is standard practice for private equity to load firms with debt. This means that taxable profits are turned into tax-deductible interest payments. The difference can be a gain to Bain and other private equity firms, but it is coming at the expense of taxpayers.

In the same vein, private equity companies often in engage in complex asset shifting. This can leave a heavily indebted firm with few valuable assets. If it eventually goes bankrupt, the creditors collect little money because the private equity company has transferred the assets with value into an independent company. This can also mean big profits for Bain and other private equity companies, but this is not a gain to the economy.

Another frequent game of private equity companies is to dump pension obligations on the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation. The reduction in liabilities can mean big profits for Bain and other private equity companies, but does not provide any benefit to the economy.

These are the sorts of issues that appear in serious discussions of the benefits of private equity.

The Post piece also included the bizarre assertion that:

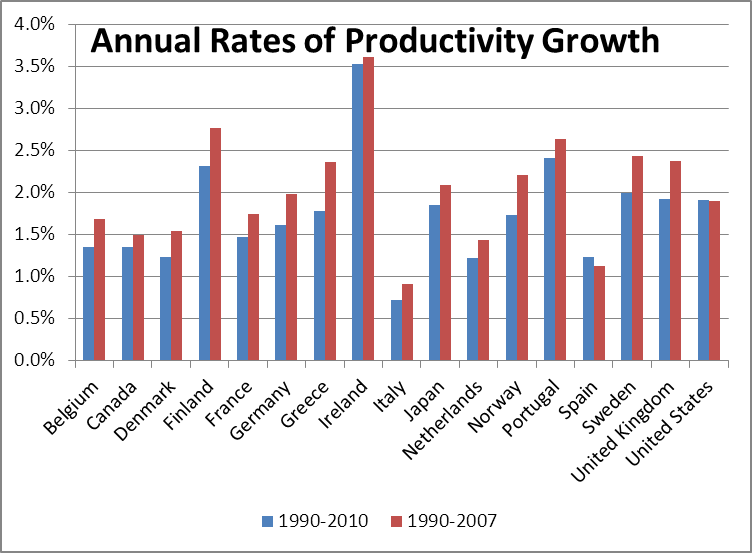

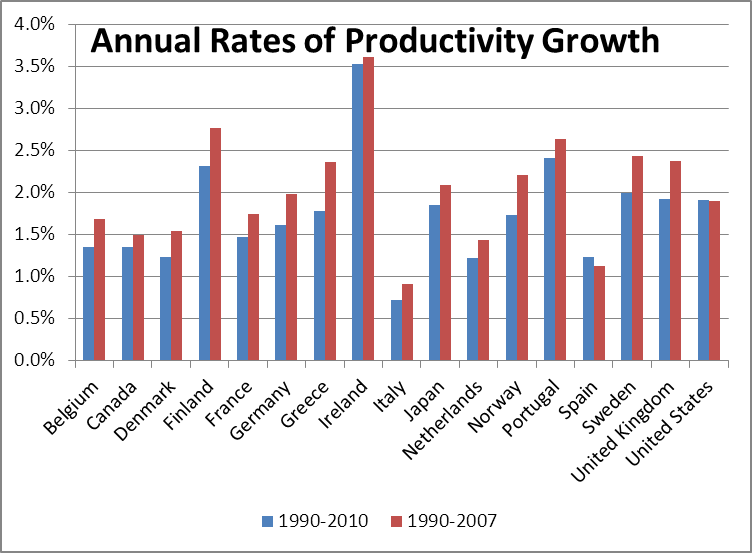

“Probably it [private equity] is one feature of U.S. capitalism that makes our system more flexible and capable of ‘creative destruction’ than Europe’s.”

This is bizarre because the U.S. economy is not obviously more flexible and capable of “creative destruction” than Europe’s economy, as people familiar with the productivity data know.

Source: OECD.

No one reads Washington Post editorials for their astute economic analysis. The paper did not surprise readers with its balanced discussion of private equity today.

While the paper is right to point out that whether private equity firms directly increase or decrease employment is not a good measure of whether they are beneficial to the economy, it totally overlooked the main issues surrounding private equity and its impact on the economy. The question is whether the high profits earned by the partners are primarily due to increasing economic efficiency or to rents earned by dumping costs on others.

As noted here, it is standard practice for private equity to load firms with debt. This means that taxable profits are turned into tax-deductible interest payments. The difference can be a gain to Bain and other private equity firms, but it is coming at the expense of taxpayers.

In the same vein, private equity companies often in engage in complex asset shifting. This can leave a heavily indebted firm with few valuable assets. If it eventually goes bankrupt, the creditors collect little money because the private equity company has transferred the assets with value into an independent company. This can also mean big profits for Bain and other private equity companies, but this is not a gain to the economy.

Another frequent game of private equity companies is to dump pension obligations on the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation. The reduction in liabilities can mean big profits for Bain and other private equity companies, but does not provide any benefit to the economy.

These are the sorts of issues that appear in serious discussions of the benefits of private equity.

The Post piece also included the bizarre assertion that:

“Probably it [private equity] is one feature of U.S. capitalism that makes our system more flexible and capable of ‘creative destruction’ than Europe’s.”

This is bizarre because the U.S. economy is not obviously more flexible and capable of “creative destruction” than Europe’s economy, as people familiar with the productivity data know.

Source: OECD.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’ve become accustomed to people in elite circles saying that I do not exist, as in “nobody saw the housing bubble,” but it still hurts. Okay, excuse the self-indulgence, there is a point here.

In his column today, David Brooks notes that rent-seekers often benefit from government programs, then complains that:

“You would think that liberals would have a special incentive to root out rent-seeking. Yet this has not been a major priority. There is no Steve Jobs figure in American liberalism insisting that the designers keep government simple, elegant and user-friendly.”

I actually have been yelling at the top of my lungs for much of the last decade about how the government has been used by the wealthy to redistribute income upward. This is the point of the not subtly titled book, The Conservative Nanny State: How the Wealthy Use the Government to Stay Rich and Get Richer. And there is my more recent book, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive. (Both are available as free e-books, for those interested.)

These books have not attracted much attention, I would be fairly certain that Brooks has never heard of either one. Some of this undoubtedly reflects my skills as a writer, but there is a deeper issue here.

The people who dominate what passes for “liberal” politics in the United States would have little interest in promoting the views expressed in these books. Would Robert Rubin and his Wall Street friends want to promote the argument that they got rich primarily because they could rely on too big to fail insurance provided at no cost by the government? Those who question the importance of Wall Street interests in the Democratic Party should note that making a fortune on Wall Street seems to be a pre-requisite for being chief of staff in the Obama administration.

Similarly, both books point out the enormous waste associated with patent and copyright protection. Patent protection for prescription drugs costs us more than $250 billion a year compared to having drugs sold in a free market. This is five times as much money as what is at stake with extending the Bush tax cuts to the richest two percent. But the Hollywood crew, another important base of funding support for the Democratic Party, have little interest in calling attention to the government interventions that keep their industry alive in its current form.

The books also note the protectionist barriers that make it difficult for foreign professionals (e.g. doctors, dentists, and lawyers) from competing with professionals in the United States. This ensures that these professionals will benefit from international trade, since the goods they buy (including trips to Europe) will be cheaper as a result of trade, while the services they sell will continue to command a high price. However, the professionals who design policy for the Democratic Party have little interest in calling attention to the barriers that protect the high pay that they and their family members enjoy.

In short, there are clear structural obstacles to those advancing an argument that we should restructure the government so that it does not redistribute income upward. Those who control the purse strings that finance politics and policy research and the institutions that dominate public debate (e.g. the New York Times, Washington Post, and National Public Radio) have a clear interest in not having this argument get a wide audience.

This is why David Brooks can tell his readers that there are no liberals who are trying to combat rent-seeking that redistributes income to the wealthy. His friends, in both parties, do their best to ensure that anyone making such arguments never gets heard.

(I should mention Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson as two people who have made a similar argument to a somewhat larger audience.)

I’ve become accustomed to people in elite circles saying that I do not exist, as in “nobody saw the housing bubble,” but it still hurts. Okay, excuse the self-indulgence, there is a point here.

In his column today, David Brooks notes that rent-seekers often benefit from government programs, then complains that:

“You would think that liberals would have a special incentive to root out rent-seeking. Yet this has not been a major priority. There is no Steve Jobs figure in American liberalism insisting that the designers keep government simple, elegant and user-friendly.”

I actually have been yelling at the top of my lungs for much of the last decade about how the government has been used by the wealthy to redistribute income upward. This is the point of the not subtly titled book, The Conservative Nanny State: How the Wealthy Use the Government to Stay Rich and Get Richer. And there is my more recent book, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive. (Both are available as free e-books, for those interested.)

These books have not attracted much attention, I would be fairly certain that Brooks has never heard of either one. Some of this undoubtedly reflects my skills as a writer, but there is a deeper issue here.

The people who dominate what passes for “liberal” politics in the United States would have little interest in promoting the views expressed in these books. Would Robert Rubin and his Wall Street friends want to promote the argument that they got rich primarily because they could rely on too big to fail insurance provided at no cost by the government? Those who question the importance of Wall Street interests in the Democratic Party should note that making a fortune on Wall Street seems to be a pre-requisite for being chief of staff in the Obama administration.

Similarly, both books point out the enormous waste associated with patent and copyright protection. Patent protection for prescription drugs costs us more than $250 billion a year compared to having drugs sold in a free market. This is five times as much money as what is at stake with extending the Bush tax cuts to the richest two percent. But the Hollywood crew, another important base of funding support for the Democratic Party, have little interest in calling attention to the government interventions that keep their industry alive in its current form.

The books also note the protectionist barriers that make it difficult for foreign professionals (e.g. doctors, dentists, and lawyers) from competing with professionals in the United States. This ensures that these professionals will benefit from international trade, since the goods they buy (including trips to Europe) will be cheaper as a result of trade, while the services they sell will continue to command a high price. However, the professionals who design policy for the Democratic Party have little interest in calling attention to the barriers that protect the high pay that they and their family members enjoy.

In short, there are clear structural obstacles to those advancing an argument that we should restructure the government so that it does not redistribute income upward. Those who control the purse strings that finance politics and policy research and the institutions that dominate public debate (e.g. the New York Times, Washington Post, and National Public Radio) have a clear interest in not having this argument get a wide audience.

This is why David Brooks can tell his readers that there are no liberals who are trying to combat rent-seeking that redistributes income to the wealthy. His friends, in both parties, do their best to ensure that anyone making such arguments never gets heard.

(I should mention Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson as two people who have made a similar argument to a somewhat larger audience.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT implies that it is when it tells readers that:

“Many of those involved [in the fracking debate] said it was unlikely that Governor Cuomo would turn his back on the gas industry and ban drilling in the rich Marcellus and Utica shale deposits covering much of the economically depressed southern and western reaches of the state.”

If the industry creates relatively few jobs, most of which go to skilled workers from outside of the state, and then leaves the area permanently scarred, it is not clear that fracking is beneficial to economically depressed areas.

The NYT implies that it is when it tells readers that:

“Many of those involved [in the fracking debate] said it was unlikely that Governor Cuomo would turn his back on the gas industry and ban drilling in the rich Marcellus and Utica shale deposits covering much of the economically depressed southern and western reaches of the state.”

If the industry creates relatively few jobs, most of which go to skilled workers from outside of the state, and then leaves the area permanently scarred, it is not clear that fracking is beneficial to economically depressed areas.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión