Every few months there is a mini-frenzy around the idea of allowing more people to refinance their mortgages. Today Ezra Klein picks up the cause in his Post column. This is a good idea, but the notion that this is going to provide some major boost to the economy is just silly.

The main reason is that there just are not that many homeowners tied into high cost mortgages who are going to be induced to take advantage of a refinancing opportunity. The story is that we have millions of homeowners who are badly underwater and therefore will not be able to meet normal refinancing criteria. However, the numbers who are being precluded from refinancing for this reason are likely relatively few at this point.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had a policy for several years of allowing people to refinance who had mortgages that were up to 125 percent of their home value. This probably accounts for close to half of the 12 million or so underwater homeowners. Of the roughly 50 percent of mortgages insured by Fannie and Freddie, it is likely that a greater share are in the under 125 percent group, since they generally did not get the worst mortgages.

In September, President Obama persuaded the Federal House Finance Administration to remove this cap, allowing anyone with a Fannie or Freddie backed mortgage to refinance no matter how much they are underwater. Undoubtedly many people are taking advantage of this opportunity as refinancing has been very strong through the fall months. (Mortgage refis tend to run around 700k to 800k a month.)

Suppose that there were 3 million homeowners with Fannie and Freddie loans that were too underwater to be able to refinance before the change in policy in September (half of the roughly 6 million mortgages that were more than 125 percent underwater). Suppose roughly a quarter of the monthly refis over the fall were from this group, which would mean that 800k have already refinanced leaving another 2.2 million.

Of this group, some number may have plans to sell their homes or for other reasons not be interested in refinancing their mortgages. Of course some would refinance even with no change in policy, but they just have not gotten around to it. Anyhow, let’s suppose that that full court press gets 2 million of these people to refinance over the next 4 months. If we assume an average mortgage of $250k (the average house price is around $225k and the median is a bit over $160k), and we assume average savings of 2 percentage points on the new mortgage, this frees up $10 billion a year.

If homeowners spend 90 percent of this freed up money, that adds $9 billion a year or 0.06 percent to demand. And, that is before deducting any reduced spending on the part of the mortgage holders who are now getting less interest. It also doesn’t take into account that many of these mortgages would have been refinanced in any case, just somewhat later in the year.

In short, Obama should do everything he can to try to make it easy for underwater homeowners to get into lower cost loans. But the reason is that it will help these homeowners, it will not have a noticeable impact on the economy.

Every few months there is a mini-frenzy around the idea of allowing more people to refinance their mortgages. Today Ezra Klein picks up the cause in his Post column. This is a good idea, but the notion that this is going to provide some major boost to the economy is just silly.

The main reason is that there just are not that many homeowners tied into high cost mortgages who are going to be induced to take advantage of a refinancing opportunity. The story is that we have millions of homeowners who are badly underwater and therefore will not be able to meet normal refinancing criteria. However, the numbers who are being precluded from refinancing for this reason are likely relatively few at this point.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had a policy for several years of allowing people to refinance who had mortgages that were up to 125 percent of their home value. This probably accounts for close to half of the 12 million or so underwater homeowners. Of the roughly 50 percent of mortgages insured by Fannie and Freddie, it is likely that a greater share are in the under 125 percent group, since they generally did not get the worst mortgages.

In September, President Obama persuaded the Federal House Finance Administration to remove this cap, allowing anyone with a Fannie or Freddie backed mortgage to refinance no matter how much they are underwater. Undoubtedly many people are taking advantage of this opportunity as refinancing has been very strong through the fall months. (Mortgage refis tend to run around 700k to 800k a month.)

Suppose that there were 3 million homeowners with Fannie and Freddie loans that were too underwater to be able to refinance before the change in policy in September (half of the roughly 6 million mortgages that were more than 125 percent underwater). Suppose roughly a quarter of the monthly refis over the fall were from this group, which would mean that 800k have already refinanced leaving another 2.2 million.

Of this group, some number may have plans to sell their homes or for other reasons not be interested in refinancing their mortgages. Of course some would refinance even with no change in policy, but they just have not gotten around to it. Anyhow, let’s suppose that that full court press gets 2 million of these people to refinance over the next 4 months. If we assume an average mortgage of $250k (the average house price is around $225k and the median is a bit over $160k), and we assume average savings of 2 percentage points on the new mortgage, this frees up $10 billion a year.

If homeowners spend 90 percent of this freed up money, that adds $9 billion a year or 0.06 percent to demand. And, that is before deducting any reduced spending on the part of the mortgage holders who are now getting less interest. It also doesn’t take into account that many of these mortgages would have been refinanced in any case, just somewhat later in the year.

In short, Obama should do everything he can to try to make it easy for underwater homeowners to get into lower cost loans. But the reason is that it will help these homeowners, it will not have a noticeable impact on the economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Eamonn Fingleton started a debate on Japan’s slump or lack thereof with a Sunday review piece in the NYT. This has since been joined by Paul Krugman and others. Since I have been asked by a number of people what I thought, I will weigh in with my own two cents.

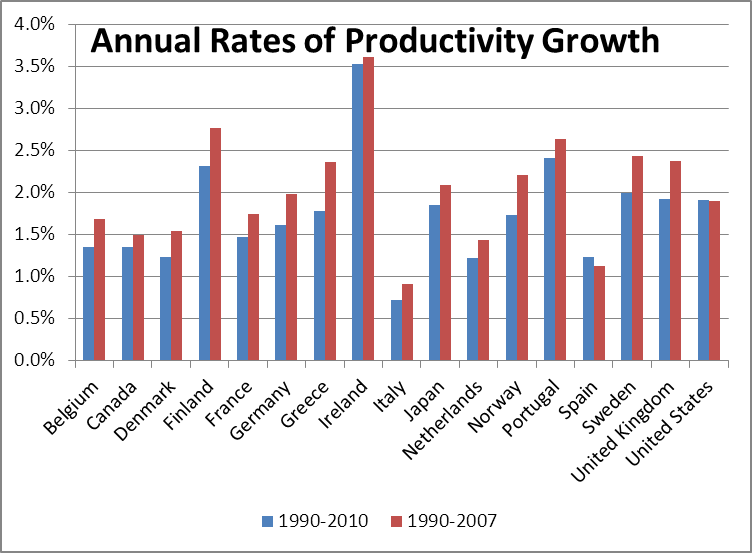

First I agree with Fingleton that the description of Japan as a basket case is way off the mark. While GDP growth has been weak, its productivity growth has been better than the average in the OECD.

Source: OECD.

The fact that its productivity growth has exceeded its GDP growth is explained by both the aging of the population, leading to a decline in the size of its labor force and also the reduction in the number of hours worked per year by the average worker. Neither of these seems to be obviously bad, although it is almost certainly the case that Japan still suffers from some hidden unemployment (mostly among women) in addition to its relatively low official unemployment (@ 4.0 percent).

Fingleton probably does go overboard in a few areas. First, Shadowstats is not a credible source. There are issues with the official statistics in the U.S. (as is the case everywhere), but the idea that we have overstated growth by 2 percentage points a year does not pass the laugh test.

Second, the measure of electricity use that he sees as a main determinant of living standards is likely distorted by the fact that Japan was starting from a very low base whereas the U.S. was starting from a very high base. We can get any number of new appliances that will be markedly better than the ones that they replaced and still use considerably less electricity. The same is not likely to be the case with Japan. The same applies to commercial and industrial users of electricity.

But there is an area in which Fingleton may actually understate his case. I remember refereeing a journal article at the end of the 90s about Japan’s price index for passenger trains. (Wait, this is not that boring.)

The article purported to show that the official Japanese index overstated inflation because it missed quality improvements. The main quality improvement was that the trains were less crowded. The author had compared the price of first class and second class seats and noted that the main difference between the two was that first class passengers were guaranteed a seat. However because the trains had become less crowded, almost everyone in second class could now get a seat as well. This in effect meant that a second class seat at the end of the period examined was as good as a first class seat at the beginning.

This made a substantial difference in the price index for trains, effectively showing a much slower rate of price increase when this quality improvement (less crowding) was taken into account. This issue could be an important factor in the quality of services across Japan more generally. If the reduced population has led to fewer people on planes and other forms of transportation, fewer people sharing parks and beaches and other potentially crowded public places, then it may imply a substantial improvement in living standards that would not be picked up in conventional economic measures.

I don’t know if anyone has researched this issue and tried to quantify the benefits that the Japanese may be receiving from reduced crowding, but it is plausible that the gains would be substantial.

Eamonn Fingleton started a debate on Japan’s slump or lack thereof with a Sunday review piece in the NYT. This has since been joined by Paul Krugman and others. Since I have been asked by a number of people what I thought, I will weigh in with my own two cents.

First I agree with Fingleton that the description of Japan as a basket case is way off the mark. While GDP growth has been weak, its productivity growth has been better than the average in the OECD.

Source: OECD.

The fact that its productivity growth has exceeded its GDP growth is explained by both the aging of the population, leading to a decline in the size of its labor force and also the reduction in the number of hours worked per year by the average worker. Neither of these seems to be obviously bad, although it is almost certainly the case that Japan still suffers from some hidden unemployment (mostly among women) in addition to its relatively low official unemployment (@ 4.0 percent).

Fingleton probably does go overboard in a few areas. First, Shadowstats is not a credible source. There are issues with the official statistics in the U.S. (as is the case everywhere), but the idea that we have overstated growth by 2 percentage points a year does not pass the laugh test.

Second, the measure of electricity use that he sees as a main determinant of living standards is likely distorted by the fact that Japan was starting from a very low base whereas the U.S. was starting from a very high base. We can get any number of new appliances that will be markedly better than the ones that they replaced and still use considerably less electricity. The same is not likely to be the case with Japan. The same applies to commercial and industrial users of electricity.

But there is an area in which Fingleton may actually understate his case. I remember refereeing a journal article at the end of the 90s about Japan’s price index for passenger trains. (Wait, this is not that boring.)

The article purported to show that the official Japanese index overstated inflation because it missed quality improvements. The main quality improvement was that the trains were less crowded. The author had compared the price of first class and second class seats and noted that the main difference between the two was that first class passengers were guaranteed a seat. However because the trains had become less crowded, almost everyone in second class could now get a seat as well. This in effect meant that a second class seat at the end of the period examined was as good as a first class seat at the beginning.

This made a substantial difference in the price index for trains, effectively showing a much slower rate of price increase when this quality improvement (less crowding) was taken into account. This issue could be an important factor in the quality of services across Japan more generally. If the reduced population has led to fewer people on planes and other forms of transportation, fewer people sharing parks and beaches and other potentially crowded public places, then it may imply a substantial improvement in living standards that would not be picked up in conventional economic measures.

I don’t know if anyone has researched this issue and tried to quantify the benefits that the Japanese may be receiving from reduced crowding, but it is plausible that the gains would be substantial.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s a good question, but Robert Samuelson doesn’t shed much light on the topic in his column today. He notes the considerable evidence of a housing bubble in parts of the country, which may now be deflating. In considering consequences he acknowledges China’s successful stimulus 3 years ago, but then comments:

“Finally, China’s government will have a harder time deploying a stimulus than during the 2008-09 financial crisis. Government debt rose from 26 percent of gross domestic product in 2007 to 43 percent of GDP in 2010.”

This one must have readers all over the world scratching their heads. A country with a debt to GDP ratio of 43 percent, that is growing at an annual rate close to 10 percent, has trouble borrowing money to finance a stimulus? That’s not true on this planet.

The United States had no problem financing its stimulus even when its debt to GDP ratio was over 60 percent, with a prospective growth rate of less than 3 percent. And Japan pays less than 1 percent interest on its debt even though it has a debt to GDP ratio of more than 200 percent of a trend growth rate under 2 percent.

It might also be a good idea if Samuelson relied on someone other than Nicholas Lardy as his expert on China’s economy. Lardy is known for predicting that China would suffer a crippling banking crisis more than a decade ago. That has not happened yet.

That’s a good question, but Robert Samuelson doesn’t shed much light on the topic in his column today. He notes the considerable evidence of a housing bubble in parts of the country, which may now be deflating. In considering consequences he acknowledges China’s successful stimulus 3 years ago, but then comments:

“Finally, China’s government will have a harder time deploying a stimulus than during the 2008-09 financial crisis. Government debt rose from 26 percent of gross domestic product in 2007 to 43 percent of GDP in 2010.”

This one must have readers all over the world scratching their heads. A country with a debt to GDP ratio of 43 percent, that is growing at an annual rate close to 10 percent, has trouble borrowing money to finance a stimulus? That’s not true on this planet.

The United States had no problem financing its stimulus even when its debt to GDP ratio was over 60 percent, with a prospective growth rate of less than 3 percent. And Japan pays less than 1 percent interest on its debt even though it has a debt to GDP ratio of more than 200 percent of a trend growth rate under 2 percent.

It might also be a good idea if Samuelson relied on someone other than Nicholas Lardy as his expert on China’s economy. Lardy is known for predicting that China would suffer a crippling banking crisis more than a decade ago. That has not happened yet.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what reporters should have been asking as the Obama administration put a positive spin on the 1.6 million job growth in 2011. The economy has to create roughly 1 million jobs a year to keep pace with the growth of the labor force. With a shortfall of jobs that is currently near 10 million, it will take more than 16 years to get the economy back to full employment at the 2011 rate of job growth.

Reporters should have been ridiculing the Obama administration for their poor grasp of arithmetic for celebrating such a dismal job performance. They certainly should have pointed out to readers the absurdity of their boasts about the recent pace of job growth.

That’s what reporters should have been asking as the Obama administration put a positive spin on the 1.6 million job growth in 2011. The economy has to create roughly 1 million jobs a year to keep pace with the growth of the labor force. With a shortfall of jobs that is currently near 10 million, it will take more than 16 years to get the economy back to full employment at the 2011 rate of job growth.

Reporters should have been ridiculing the Obama administration for their poor grasp of arithmetic for celebrating such a dismal job performance. They certainly should have pointed out to readers the absurdity of their boasts about the recent pace of job growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Economists tend not to be very good at economics. We know this because almost none of them were able to see the $8 trillion housing bubble that was driving the economy from 2002 to 2007. This was an oversight of astonishing importance, sort of like a physicist not noticing gravity.

Their failure to understand the economy has led to enormous misreporting of the December jobs data. There are two basic problems. They fail to accurately put the job growth numbers in the context of the economic downturn and they badly misread the December data leading them to overstate the true growth path we are now on.

Taking the two in turn, the reports were full of the good news that the economy had created 200,000 jobs and the unemployment rate had dropped to 8.5 percent. Creating 200,000 jobs is undoubtedly better than creating 100,000 jobs and much better than creating no jobs at all, but is this good?

From December of 1995 to December of 1999 the economy generated more than 250,000 jobs a month, and that was starting from an unemployment rate of under 6.0 percent. We expect more rapid job growth following a steep downturn like the one we saw in 2007-2009.

In the two years following the 1981-82 recession the economy generated over 300,000 jobs a month. Following the 1974-75 recession, the economy generated more than 340,000 jobs a month in the two years from December 1976 to December 1978, and this was with a labor force that was only 60 percent of the size of the current labor force. So we’re supposed to be happy about 200,000 jobs in December?

Another way to think about this is that we currently have a shortfall of around 10 million jobs. If we generate 200,000 jobs a month, then we are cutting into this shortfall at the rate of 100,000 a month, since we need 90,000-100,000 jobs a month just to keep pace with the growth of the population. This means that in 100 months we should expect to be back to full employment. So the champagne bottles for that happy occasion will be dated 2020.

Okay, but this puts too bright of a picture on the data. The 200,000 jobs number reported for December was distorted by unusual seasonal factors, the most obvious of which was the 42,200 job growth reported in the courier industry. This is primarily companies like Fed Ex and UPS who hire additional workers to deal with holiday demand.

In principle seasonal adjustments should remove the impact of seasonal fluctuations, however these adjustments are always based on historical experience. When there is a sharp departure from historical patterns, like the explosion of Internet sales, the seasonal adjustments will not pick this up. We have good reason for believing this to be the case here because in 2010 the Labor Department reported an increase of 46,300 jobs in the courier industry, all of which disappeared the next month. In 2009, it was 30,100 jobs reported in December that all disappeared in January.

Here’s the picture:

Employment in Couriers and Messengers (seasonally adjusted)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

What should we infer from this? We should assume that most, is not all of these 42,200 jobs reported in December will disappear in January. That puts our jobs number around 160,000. There were some other unusual factors that may have pumped the numbers in December slightly. Construction employment reportedly rose 17,000 in December after falling 10,000 in October and 12,000 in November. Did we turn the corner in the construction industry? Well the sector added 31,000 jobs in September. Construction employment is very erratic because of the weather. We had a relatively mild December in the Northeast and Midwest, which means that we would expect better than usual construction employment. Don’t bet on this one being part of a trend.

There were a few other anomalies of less consequence in both directions, but a clear-eyed look at the December data puts the job growth at around 150,000. If we take the average job growth over the last three months we get roughly 140,000. Maybe we have a slight pick-up, but probably not much more. At 150,000 jobs a month, the full employment champagne bottles will be dated 2028.

What about the drop in the unemployment rate, surely that is good news? Well the unemployment data come from a separate survey of households. This survey is much more erratic than the establishment survey due to the fact that it has a much smaller sample. There are often large movements in this survey that clearly cannot be explained by movements in the economy.

For example, the survey showed the unemployment rate falling from 4.7 to 4.4 percent in the second half of 2006, a period when GDP growth averaged 1.4 percent. It then rose back to 4.7 percent in the first half of 2007, a period when growth averaged 2.1 percent. The monthly employment changes can be even more erratic. In the four months from July to November 1994, the survey showed the economy adding almost 1.8 million jobs or 450,000 a month. This was a period in which the economy was growing at a healthy, but not spectacular, 3.6 percent annual rate.

More recently, the survey showed employment plunging by 423,000 last June. Fortunately no one thought to seize on that change as marking the start of another recession. Over the course of a year, these erratic movements largely even out. If we look at employment from December of 2010 to December of 2011, it increased by 1,570,000 in the household survey. This is telling us pretty much the same story as the rise in payroll employment over this period of 1,640,000 jobs.

The other point to remember is that the unemployment rate is telling us not how many people are out of work, but rather how many people are out of work and looking for jobs. Many people give up looking for work if they feel their job prospects are hopeless. A better measure for most purposes is the employment to population ratio (EPOP). By this measure, we have made little progress since the trough of the recession.

The 58.5 percent number for December is up just 0.3 percentage points from the trough of 58.2 percent hit last summer. By comparison, the EPOP hit a peak of 63.4 percent in 2006. We still have almost 5 percentage points to go before we get back to this pre-recession peak. Or to put it slightly differently: we have made up just 6 percent of the lost ground.

Employment to Population Ratio

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In short, a serious look at the December report does not provide much cause for celebration. The economy is still in very bad shape and the current growth path provides little hope for much relief any time soon. Economists should know this, but unfortunately few seem to pay much attention to the data. Remember the double-dip recession?

Economists tend not to be very good at economics. We know this because almost none of them were able to see the $8 trillion housing bubble that was driving the economy from 2002 to 2007. This was an oversight of astonishing importance, sort of like a physicist not noticing gravity.

Their failure to understand the economy has led to enormous misreporting of the December jobs data. There are two basic problems. They fail to accurately put the job growth numbers in the context of the economic downturn and they badly misread the December data leading them to overstate the true growth path we are now on.

Taking the two in turn, the reports were full of the good news that the economy had created 200,000 jobs and the unemployment rate had dropped to 8.5 percent. Creating 200,000 jobs is undoubtedly better than creating 100,000 jobs and much better than creating no jobs at all, but is this good?

From December of 1995 to December of 1999 the economy generated more than 250,000 jobs a month, and that was starting from an unemployment rate of under 6.0 percent. We expect more rapid job growth following a steep downturn like the one we saw in 2007-2009.

In the two years following the 1981-82 recession the economy generated over 300,000 jobs a month. Following the 1974-75 recession, the economy generated more than 340,000 jobs a month in the two years from December 1976 to December 1978, and this was with a labor force that was only 60 percent of the size of the current labor force. So we’re supposed to be happy about 200,000 jobs in December?

Another way to think about this is that we currently have a shortfall of around 10 million jobs. If we generate 200,000 jobs a month, then we are cutting into this shortfall at the rate of 100,000 a month, since we need 90,000-100,000 jobs a month just to keep pace with the growth of the population. This means that in 100 months we should expect to be back to full employment. So the champagne bottles for that happy occasion will be dated 2020.

Okay, but this puts too bright of a picture on the data. The 200,000 jobs number reported for December was distorted by unusual seasonal factors, the most obvious of which was the 42,200 job growth reported in the courier industry. This is primarily companies like Fed Ex and UPS who hire additional workers to deal with holiday demand.

In principle seasonal adjustments should remove the impact of seasonal fluctuations, however these adjustments are always based on historical experience. When there is a sharp departure from historical patterns, like the explosion of Internet sales, the seasonal adjustments will not pick this up. We have good reason for believing this to be the case here because in 2010 the Labor Department reported an increase of 46,300 jobs in the courier industry, all of which disappeared the next month. In 2009, it was 30,100 jobs reported in December that all disappeared in January.

Here’s the picture:

Employment in Couriers and Messengers (seasonally adjusted)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

What should we infer from this? We should assume that most, is not all of these 42,200 jobs reported in December will disappear in January. That puts our jobs number around 160,000. There were some other unusual factors that may have pumped the numbers in December slightly. Construction employment reportedly rose 17,000 in December after falling 10,000 in October and 12,000 in November. Did we turn the corner in the construction industry? Well the sector added 31,000 jobs in September. Construction employment is very erratic because of the weather. We had a relatively mild December in the Northeast and Midwest, which means that we would expect better than usual construction employment. Don’t bet on this one being part of a trend.

There were a few other anomalies of less consequence in both directions, but a clear-eyed look at the December data puts the job growth at around 150,000. If we take the average job growth over the last three months we get roughly 140,000. Maybe we have a slight pick-up, but probably not much more. At 150,000 jobs a month, the full employment champagne bottles will be dated 2028.

What about the drop in the unemployment rate, surely that is good news? Well the unemployment data come from a separate survey of households. This survey is much more erratic than the establishment survey due to the fact that it has a much smaller sample. There are often large movements in this survey that clearly cannot be explained by movements in the economy.

For example, the survey showed the unemployment rate falling from 4.7 to 4.4 percent in the second half of 2006, a period when GDP growth averaged 1.4 percent. It then rose back to 4.7 percent in the first half of 2007, a period when growth averaged 2.1 percent. The monthly employment changes can be even more erratic. In the four months from July to November 1994, the survey showed the economy adding almost 1.8 million jobs or 450,000 a month. This was a period in which the economy was growing at a healthy, but not spectacular, 3.6 percent annual rate.

More recently, the survey showed employment plunging by 423,000 last June. Fortunately no one thought to seize on that change as marking the start of another recession. Over the course of a year, these erratic movements largely even out. If we look at employment from December of 2010 to December of 2011, it increased by 1,570,000 in the household survey. This is telling us pretty much the same story as the rise in payroll employment over this period of 1,640,000 jobs.

The other point to remember is that the unemployment rate is telling us not how many people are out of work, but rather how many people are out of work and looking for jobs. Many people give up looking for work if they feel their job prospects are hopeless. A better measure for most purposes is the employment to population ratio (EPOP). By this measure, we have made little progress since the trough of the recession.

The 58.5 percent number for December is up just 0.3 percentage points from the trough of 58.2 percent hit last summer. By comparison, the EPOP hit a peak of 63.4 percent in 2006. We still have almost 5 percentage points to go before we get back to this pre-recession peak. Or to put it slightly differently: we have made up just 6 percent of the lost ground.

Employment to Population Ratio

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In short, a serious look at the December report does not provide much cause for celebration. The economy is still in very bad shape and the current growth path provides little hope for much relief any time soon. Economists should know this, but unfortunately few seem to pay much attention to the data. Remember the double-dip recession?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Adam Davidson tells us in the NYT Magazine that Europe is losing its ability to compete in the world economy. This is a bit hard to see.

First, the most simple measure of competitiveness is the market test. Is Europe able to sell goods and services successfully in the world economy? On this score the continent is doing much better than the United States. Over the last decade it generally had near balanced trade. Some years the European Union had small trade surpluses and in others it had small deficits. Of course the picture differs by country. Spain and Greece had large trade deficits while Germany had large trade surpluses, but the continent as a whole had pretty much balanced trade.

This contrasts with the United States, which ran large trade deficits over most of the decade, with a peak of nearly 6.0 percent of GDP in 2006. In short, by this market test it is the United States, not Europe, that has difficulty competing.

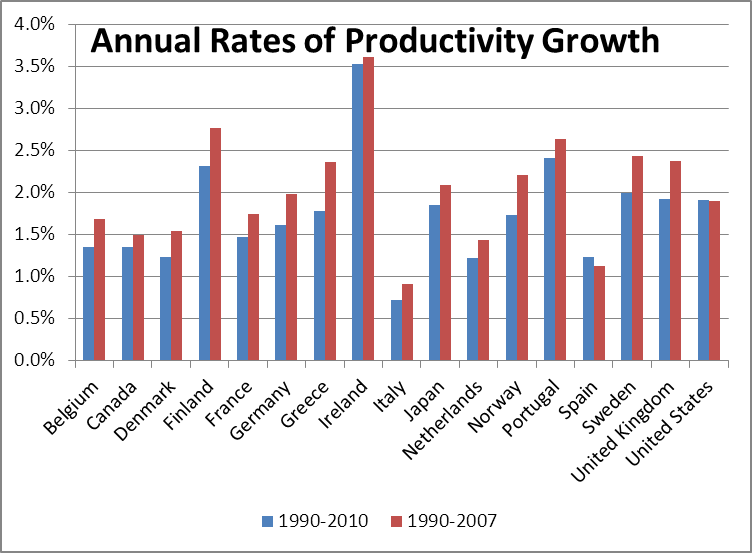

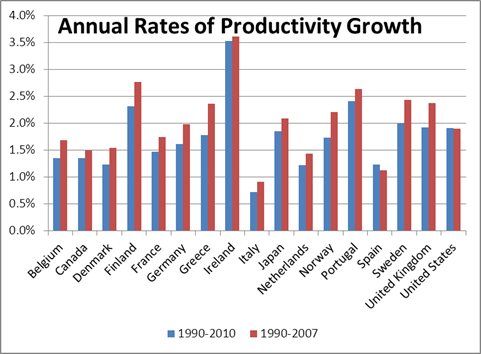

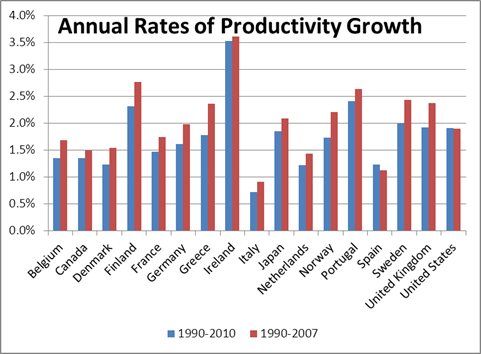

The second issue is whether productivity is growing at a decent pace. After all, this is the main long-run determinant of living standards. If we compare productivity growth in Europe with the United States it is hard to see the case for the imminent collapse of Europe.

Source: OECD.

U.S. productivity growth over this period is better than growth in Spain and Italy, but worse than Norway and Sweden. Productivity growth in the U.S. is virtually the same as in Germany and only slightly faster than in France. (The reason for showing 2007 and 2010 as separate endpoints is that many European countries have aggressively promoted policies to keep people at work during the downturn. This lowers unemployment — the unemployment rate in Germany is just 5.5 percent — but it also reduces productivity.) Productivity is difficult to measure and international comparisons should always be viewed with caution, but it is hard to make the case here for a European continent that faced serious economic problems before the economic crisis.

There is the more subjective view of competitiveness involving items like successful tech companies and relative importance in the new economy. Even here the case is not clear. After all, one of the key developers of Linux was Linus Torvalds, a Finn. Nokia has lost market share recently but had been the world’s leading cell phone manufacturer. The Swedish company, Ericsson was another leading cell producer.

On measures of connectivity there is considerable variability across Europe. Northern European countries like Norway and Denmark tend to rank higher than the U.S. on areas like broadband penetration, Germany and France are comparable, and the southern European countries rank lower. On educational outcomes, by most measures, most of Europe does better.

In short, it would be difficult to find a generally accepted measure of competitiveness where Europe does poorly compared to the United States. The European Central Bank may be able to inflict enough damage so that in a few years this is no longer the case, but for now Europe’s fundamentals still seem solid.

Adam Davidson tells us in the NYT Magazine that Europe is losing its ability to compete in the world economy. This is a bit hard to see.

First, the most simple measure of competitiveness is the market test. Is Europe able to sell goods and services successfully in the world economy? On this score the continent is doing much better than the United States. Over the last decade it generally had near balanced trade. Some years the European Union had small trade surpluses and in others it had small deficits. Of course the picture differs by country. Spain and Greece had large trade deficits while Germany had large trade surpluses, but the continent as a whole had pretty much balanced trade.

This contrasts with the United States, which ran large trade deficits over most of the decade, with a peak of nearly 6.0 percent of GDP in 2006. In short, by this market test it is the United States, not Europe, that has difficulty competing.

The second issue is whether productivity is growing at a decent pace. After all, this is the main long-run determinant of living standards. If we compare productivity growth in Europe with the United States it is hard to see the case for the imminent collapse of Europe.

Source: OECD.

U.S. productivity growth over this period is better than growth in Spain and Italy, but worse than Norway and Sweden. Productivity growth in the U.S. is virtually the same as in Germany and only slightly faster than in France. (The reason for showing 2007 and 2010 as separate endpoints is that many European countries have aggressively promoted policies to keep people at work during the downturn. This lowers unemployment — the unemployment rate in Germany is just 5.5 percent — but it also reduces productivity.) Productivity is difficult to measure and international comparisons should always be viewed with caution, but it is hard to make the case here for a European continent that faced serious economic problems before the economic crisis.

There is the more subjective view of competitiveness involving items like successful tech companies and relative importance in the new economy. Even here the case is not clear. After all, one of the key developers of Linux was Linus Torvalds, a Finn. Nokia has lost market share recently but had been the world’s leading cell phone manufacturer. The Swedish company, Ericsson was another leading cell producer.

On measures of connectivity there is considerable variability across Europe. Northern European countries like Norway and Denmark tend to rank higher than the U.S. on areas like broadband penetration, Germany and France are comparable, and the southern European countries rank lower. On educational outcomes, by most measures, most of Europe does better.

In short, it would be difficult to find a generally accepted measure of competitiveness where Europe does poorly compared to the United States. The European Central Bank may be able to inflict enough damage so that in a few years this is no longer the case, but for now Europe’s fundamentals still seem solid.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There he goes again, Paul Krugman is ignoring history to make the Republicans look better. His column today takes issue with Republican front-runner Mitt Romney’s claim that the economy has lost 2 million jobs during the Obama administration. Krugman points out that all the job loss took place in the first six months of the Obama administration. When President Obama took office the economy was losing 700,000 jobs a month. The rate of job growth slowed in the late spring and summer, coinciding with the stimulus beginning to kick in. By the end of the year employment had stabilized. It has been rising slowly in the subsequent two years.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Krugman points out that the Republicans routinely talk about the job growth record of President Bush beginning in 2003, ignoring the first two years of his administration during which the economy lost over 2 million jobs. However, Krugman ignores the fact that Republicans also routinely talked about the job growth record of President Reagan as beginning in 1983, ignoring the first two years of the Reagan administration. This was also a period in which the economy lost more than 2 million jobs.

In short, it is standard practice for Republicans to ignore the beginning of a president’s term, attributing the bad events of that period to their predecessor. In President Obama’s case, Mitt Romney is applying a different and obviously absurd standard that holds him responsible for the economic collapse that was already in process at the time he took office. (Romney would be right to say that the job growth under President Obama has been pathetic.)

There he goes again, Paul Krugman is ignoring history to make the Republicans look better. His column today takes issue with Republican front-runner Mitt Romney’s claim that the economy has lost 2 million jobs during the Obama administration. Krugman points out that all the job loss took place in the first six months of the Obama administration. When President Obama took office the economy was losing 700,000 jobs a month. The rate of job growth slowed in the late spring and summer, coinciding with the stimulus beginning to kick in. By the end of the year employment had stabilized. It has been rising slowly in the subsequent two years.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Krugman points out that the Republicans routinely talk about the job growth record of President Bush beginning in 2003, ignoring the first two years of his administration during which the economy lost over 2 million jobs. However, Krugman ignores the fact that Republicans also routinely talked about the job growth record of President Reagan as beginning in 1983, ignoring the first two years of the Reagan administration. This was also a period in which the economy lost more than 2 million jobs.

In short, it is standard practice for Republicans to ignore the beginning of a president’s term, attributing the bad events of that period to their predecessor. In President Obama’s case, Mitt Romney is applying a different and obviously absurd standard that holds him responsible for the economic collapse that was already in process at the time he took office. (Romney would be right to say that the job growth under President Obama has been pathetic.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Suppose that a candidate, with no evidence whatsoever, accuses his opponent of being a child molester. Should the media simply report the accusation and the corresponding denial and not point out the fact that there is no evidence for the accusation?

This is the standard that the NYT uses in reporting Mitt Romney’s claim that:

“Mr. Obama seeks a ‘European-style welfare state’ to redistribute wealth and create ‘equal outcomes’ regardless of individual effort and success.”

The article points out that President Obama’s supporters object to this characterization of his policies, but it fails to note that there is no evidence whatsoever for Romney’s claim. In making this assertion, Romney is just making things up.

The media are being irresponsible when they imply that there is credence to a totally fabricated assertion. The responsible way to report on Romney’s accusation is that he is inventing charges against President Obama, just as if he started calling President Obama a child molester based on no evidence whatsoever.

Suppose that a candidate, with no evidence whatsoever, accuses his opponent of being a child molester. Should the media simply report the accusation and the corresponding denial and not point out the fact that there is no evidence for the accusation?

This is the standard that the NYT uses in reporting Mitt Romney’s claim that:

“Mr. Obama seeks a ‘European-style welfare state’ to redistribute wealth and create ‘equal outcomes’ regardless of individual effort and success.”

The article points out that President Obama’s supporters object to this characterization of his policies, but it fails to note that there is no evidence whatsoever for Romney’s claim. In making this assertion, Romney is just making things up.

The media are being irresponsible when they imply that there is credence to a totally fabricated assertion. The responsible way to report on Romney’s accusation is that he is inventing charges against President Obama, just as if he started calling President Obama a child molester based on no evidence whatsoever.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

All the news reports on the December jobs data are very upbeat about the 200,000 jobs reported for December. The phrase for the day is “better than expected.” However, as someone who told friends and family it would be 165,000, I see it as slightly worse than expected.

Look at the data boys and girls. We created 42,200 courier jobs in December. Was there really a big surge in hiring in the courier industry? Well, the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed a surge of more than 50,000 new courier jobs last December, all of which were gone in January and then some. In other words, pull out our 42,000 courier jobs and we are looking at job growth of 158,000, not much to celebrate.

By the way, even 200,000 jobs would not be much to celebrate. Job growth averaged almost 250,000 a month for the years 1996-2000. Coming out of a steep recession, we should be expecting job growth in the 300k-400k monthly range. Unfortunately, there has been a huge effort to lower expectations so that we come to accept dismal economic performance as the best we can do. (The double-dip recession crew deserve a special flogging in this story.)

All the news reports on the December jobs data are very upbeat about the 200,000 jobs reported for December. The phrase for the day is “better than expected.” However, as someone who told friends and family it would be 165,000, I see it as slightly worse than expected.

Look at the data boys and girls. We created 42,200 courier jobs in December. Was there really a big surge in hiring in the courier industry? Well, the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed a surge of more than 50,000 new courier jobs last December, all of which were gone in January and then some. In other words, pull out our 42,000 courier jobs and we are looking at job growth of 158,000, not much to celebrate.

By the way, even 200,000 jobs would not be much to celebrate. Job growth averaged almost 250,000 a month for the years 1996-2000. Coming out of a steep recession, we should be expecting job growth in the 300k-400k monthly range. Unfortunately, there has been a huge effort to lower expectations so that we come to accept dismal economic performance as the best we can do. (The double-dip recession crew deserve a special flogging in this story.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

People are inclined to give much more legitimacy to market outcomes than policy outcomes engineered by governments. That is why there is a whole industry devoted to convincing people that the upward redistribution of income over the last three decades, which has given the bulk of economic gains to the One Percent, is really just the result of the natural workings of the market.

David Ignatius is one of the people who works in this industry. His Post column today urges readers to contemplate the awful thought that, quoting Francis Fukuyama:

“What if the further development of technology and globalization undermines the middle class and makes it impossible for more than a minority of citizens in an advanced society to achieve middle-class status?”

It is very useful to the One Percent to pretend that their wealth and the near stagnation in living standards for everyone else is just the result of “the further development of technology and globalization.” However this has nothing to do with reality.

Globalization has hurt the living standards of the middle class because it was designed to have this effect. Trade agreements like NAFTA were quite explicitly designed to make it as easy as possible for General Electric and other manufacturers to set up operations in the developing world and export their output back to the United States. This has the effect of putting U.S. manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world.

We could have designed these deals to put our doctors, lawyers, economists and other highly paid professionals in direct competition with their much lower paid counterparts in the developing world. We could have constructed trade deals that remove all the obstacles that make it difficult for students in China, India, and elsewhere and to train to U.S. standards and then practice their professions in the United States.

If globalization had followed this path it would have produced enormous benefits to both the middle class and the economy as a whole. We would be able to get health care, university education and many other services provided by highly paid professionals at much lower cost.

In the same vein it is not technology by itself that has made some people very rich. It is largely government-granted patent and copyright monopolies that have made people rich. These polices are becoming increasingly inefficient mechanisms for supporting innovation and creative work.

In the case of prescription drugs alone, patent monopolies raise costs by more than $250 billion (@1.7 percent of GDP) a year compared to a situation in which drugs were sold in a free market. This amount is roughly 5 times as much as the amount that is at stake with extending the Bush tax cuts to the richest 2 percent of taxpayers. There are more efficient mechanisms for financing drug research however this topic is largely excluded from public debate.

The great fortunes that have been made on Wall Street come in part from implicit too-big-to-fail insurance from the government, exemption from fraud laws, and being granted special tax treatment. Even the International Monetary Fund has noted that the financial sector in the U.S. and elsewhere faces a much lower tax burden than other sectors.

If a town has twenty gambling casinos and 19 of them pay heavy taxes, then we would expect the 20th casino to enjoy much higher profits. This is a significant part of the story of the high pay and big profits on Wall Street.

There is a much longer list of ways in which the government redistributes income upwards. It is cute how people like Fukuyama and Ignatius pretend that the upward redistribution was just the natural workings of the market and then wring their hands over the unfortunate implications, but this is kids’ stuff. Serious people need not pay attention to such nonsense.

People are inclined to give much more legitimacy to market outcomes than policy outcomes engineered by governments. That is why there is a whole industry devoted to convincing people that the upward redistribution of income over the last three decades, which has given the bulk of economic gains to the One Percent, is really just the result of the natural workings of the market.

David Ignatius is one of the people who works in this industry. His Post column today urges readers to contemplate the awful thought that, quoting Francis Fukuyama:

“What if the further development of technology and globalization undermines the middle class and makes it impossible for more than a minority of citizens in an advanced society to achieve middle-class status?”

It is very useful to the One Percent to pretend that their wealth and the near stagnation in living standards for everyone else is just the result of “the further development of technology and globalization.” However this has nothing to do with reality.

Globalization has hurt the living standards of the middle class because it was designed to have this effect. Trade agreements like NAFTA were quite explicitly designed to make it as easy as possible for General Electric and other manufacturers to set up operations in the developing world and export their output back to the United States. This has the effect of putting U.S. manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world.

We could have designed these deals to put our doctors, lawyers, economists and other highly paid professionals in direct competition with their much lower paid counterparts in the developing world. We could have constructed trade deals that remove all the obstacles that make it difficult for students in China, India, and elsewhere and to train to U.S. standards and then practice their professions in the United States.

If globalization had followed this path it would have produced enormous benefits to both the middle class and the economy as a whole. We would be able to get health care, university education and many other services provided by highly paid professionals at much lower cost.

In the same vein it is not technology by itself that has made some people very rich. It is largely government-granted patent and copyright monopolies that have made people rich. These polices are becoming increasingly inefficient mechanisms for supporting innovation and creative work.

In the case of prescription drugs alone, patent monopolies raise costs by more than $250 billion (@1.7 percent of GDP) a year compared to a situation in which drugs were sold in a free market. This amount is roughly 5 times as much as the amount that is at stake with extending the Bush tax cuts to the richest 2 percent of taxpayers. There are more efficient mechanisms for financing drug research however this topic is largely excluded from public debate.

The great fortunes that have been made on Wall Street come in part from implicit too-big-to-fail insurance from the government, exemption from fraud laws, and being granted special tax treatment. Even the International Monetary Fund has noted that the financial sector in the U.S. and elsewhere faces a much lower tax burden than other sectors.

If a town has twenty gambling casinos and 19 of them pay heavy taxes, then we would expect the 20th casino to enjoy much higher profits. This is a significant part of the story of the high pay and big profits on Wall Street.

There is a much longer list of ways in which the government redistributes income upwards. It is cute how people like Fukuyama and Ignatius pretend that the upward redistribution was just the natural workings of the market and then wring their hands over the unfortunate implications, but this is kids’ stuff. Serious people need not pay attention to such nonsense.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión