David Leonhardt does some seriously bad induction when he tells readers that:

“Over the last 50 years, every time that job growth has been as meager as it has been over the last four months, the economy has been headed toward recession, in a recession or in the immediate aftermath of one.”

The problem in this story is that over most of this period the underlying rate of labor force growth was close to 2 million a year. It currently is around 1 million a year. The reason for the falloff is that the baby boom cohort is now retiring in large numbers and also there is little room for women’s labor force participation to increase. Therefore we should be expecting a considerably lower rate of job growth.

The other problem in this picture is that a recession requires some component of spending to go into reverse and turn negative. In the past, it had always been housing and car buying which fell at double-digit rates at the start of a downturn. With these categories of spending already very low, there are few obvious candidates.

Government spending has been falling, but this has been at around a 2 percent annual rate. This is a drag on growth, but a sector comprising 20 percent of GDP shrinking at a 2 percent annual rate will not throw the economy into a recession.

The one plausible cause of a double-dip would be a collapse of the euro followed by another Lehman-type freeze up on the financial system. While this could certainly lead to a second recession, the causes will be found in the failures of Euro zone politics and the ECB, not an analysis of the U.S. economy.

David Leonhardt does some seriously bad induction when he tells readers that:

“Over the last 50 years, every time that job growth has been as meager as it has been over the last four months, the economy has been headed toward recession, in a recession or in the immediate aftermath of one.”

The problem in this story is that over most of this period the underlying rate of labor force growth was close to 2 million a year. It currently is around 1 million a year. The reason for the falloff is that the baby boom cohort is now retiring in large numbers and also there is little room for women’s labor force participation to increase. Therefore we should be expecting a considerably lower rate of job growth.

The other problem in this picture is that a recession requires some component of spending to go into reverse and turn negative. In the past, it had always been housing and car buying which fell at double-digit rates at the start of a downturn. With these categories of spending already very low, there are few obvious candidates.

Government spending has been falling, but this has been at around a 2 percent annual rate. This is a drag on growth, but a sector comprising 20 percent of GDP shrinking at a 2 percent annual rate will not throw the economy into a recession.

The one plausible cause of a double-dip would be a collapse of the euro followed by another Lehman-type freeze up on the financial system. While this could certainly lead to a second recession, the causes will be found in the failures of Euro zone politics and the ECB, not an analysis of the U.S. economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT wrongly told readers that the payroll tax cut cost Social Security, “resulted in $67.2 billion of lost revenue for Social Security in 2011.” This is not true. The tax cut was fully offset by money from general revenue so that the trust fund was unaffected by the tax cut.

The NYT wrongly told readers that the payroll tax cut cost Social Security, “resulted in $67.2 billion of lost revenue for Social Security in 2011.” This is not true. The tax cut was fully offset by money from general revenue so that the trust fund was unaffected by the tax cut.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s right, he said it in his column today. He approvingly quoted Kishore Mahbubani, a retired diplomat who is now the dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore:

“No U.S. leaders dare to tell the truth to the people. All their pronouncements rest on a mythical assumption that ‘recovery’ is around the corner. Implicitly, they say this is a normal recession. But this is no normal recession. There will be no painless solution. ‘Sacrifice’ will be needed, and the American people know this. But no American politician dares utter the word ‘sacrifice.’ Painful truths cannot be told.”

Sacrifice is wonderful if it serves a purpose, but there are two big unanswered questions. First how would sacrifice help the recovery right now and second, exactly who do Mr. Friedman and Mahbubani think should be doing the sacrificing?

On the first question, I suppose that Friedman and Mahbubani want to see taxes increased or benefits like Social Security and Medicare cut. Both of these steps would mean real sacrifices for low and middle class people, but how exactly do they help the recovery?

Remember our problem is too little demand. So we make people sacrifice by paying higher taxes. How does this increase demand? Or we cut their Social Security benefits or make them pay more for their Medicare. Again, this would imply real sacrifice, but how does this spur the economy?

Are there businesses out there who are saying that they will not hire or invest today because Social Security and Medicare are too generous? Will these businesses decide to hire more workers and expand their business if the government cut these benefits?

In more normal times, there was at least a plausible argument that this could be the case. The story would go that reducing the deficit would lower interest rates, thereby encouraging businesses to invest. (Actually most research shows that investment is not very responsive to interest rates.) However, with interest rates already at post-Depression lows, it is difficult to envision them going much lower, nor that there would be much additional investment even if they did. In other words, Friedman and Mahbubani seem to be calling for pointless sacrifice.

The second part of the story is who they want to sacrifice. The top 10 percent of income distribution received the vast majority of the gains from economic growth over the last three decades. A grossly disproportionate share went to the top 1.0 percent and the top 0.1 percent. It might be reasonable to expect that the big gainers over this period would be the ones who should be doing the sacrificing.

But not in Thomas Friedman’s world. In his world, sacrifice must be shared equally. Those who are incredibly rich and those who are barely getting by are both called upon to make sacrifices for the greater good. That’s Thomas Friedman justice.

That’s right, he said it in his column today. He approvingly quoted Kishore Mahbubani, a retired diplomat who is now the dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore:

“No U.S. leaders dare to tell the truth to the people. All their pronouncements rest on a mythical assumption that ‘recovery’ is around the corner. Implicitly, they say this is a normal recession. But this is no normal recession. There will be no painless solution. ‘Sacrifice’ will be needed, and the American people know this. But no American politician dares utter the word ‘sacrifice.’ Painful truths cannot be told.”

Sacrifice is wonderful if it serves a purpose, but there are two big unanswered questions. First how would sacrifice help the recovery right now and second, exactly who do Mr. Friedman and Mahbubani think should be doing the sacrificing?

On the first question, I suppose that Friedman and Mahbubani want to see taxes increased or benefits like Social Security and Medicare cut. Both of these steps would mean real sacrifices for low and middle class people, but how exactly do they help the recovery?

Remember our problem is too little demand. So we make people sacrifice by paying higher taxes. How does this increase demand? Or we cut their Social Security benefits or make them pay more for their Medicare. Again, this would imply real sacrifice, but how does this spur the economy?

Are there businesses out there who are saying that they will not hire or invest today because Social Security and Medicare are too generous? Will these businesses decide to hire more workers and expand their business if the government cut these benefits?

In more normal times, there was at least a plausible argument that this could be the case. The story would go that reducing the deficit would lower interest rates, thereby encouraging businesses to invest. (Actually most research shows that investment is not very responsive to interest rates.) However, with interest rates already at post-Depression lows, it is difficult to envision them going much lower, nor that there would be much additional investment even if they did. In other words, Friedman and Mahbubani seem to be calling for pointless sacrifice.

The second part of the story is who they want to sacrifice. The top 10 percent of income distribution received the vast majority of the gains from economic growth over the last three decades. A grossly disproportionate share went to the top 1.0 percent and the top 0.1 percent. It might be reasonable to expect that the big gainers over this period would be the ones who should be doing the sacrificing.

But not in Thomas Friedman’s world. In his world, sacrifice must be shared equally. Those who are incredibly rich and those who are barely getting by are both called upon to make sacrifices for the greater good. That’s Thomas Friedman justice.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Brooks told readers today that there are no jobs in the green economy. While many political figures may have oversold the prospect for green jobs, the case that Brooks musters is much less clear than he suggests. For example, he tells us that:

“California was awarded $186 million in federal stimulus money to weatherize homes. So far, the program has created the equivalent of only 538 full-time jobs.”

While that may sound like a pretty bad spending to jobs ratio, if we go to the article that Brooks references, we see that the main problem is that only a bit more than half of the money has been spent. If we say that $100 million has been spent to get us 238 jobs, that translates into $186,000 a job. That’s not great, but if we had the same ratio for the whole stimulus (counting the AMT) then it would translate into 4.2 million jobs. Given that this money comes at essentially zero cost right now (the real interest rate on government debt is negative), this doesn’t seem like too bad a way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

He then tells us that:

“executives at Johnson Controls turned $300 million in green technology grants into 150 jobs — that’s $2 million per job.”

Okay, this is big-time sloppy. Most of the jobs created when people buy a GM car are not at General Motors. Most of the jobs created when people buy an iPad are not at Apple. If Brooks wants to find out how many jobs were created by this $300 million in green technology grants he will have to go beyond the executives at Johnson Controls and talk to suppliers. Who knows what this will uncover (they may all be in China), but the fact that Johnson Controls did not create many jobs really doesn’t tell us anything.

However, the best story in Brooks’ arsenal is his complaint about the Smart Grids Initiative. Based on a story from the Washington Post, he tells us that:

“the Smart Grid, while efficient and environmentally beneficial, will be a net job destroyer. For example, 28,000 meter-reading jobs will be replaced by the Smart Grid’s automatic transmitters.”

If we turn to the piece, we see that the Smart Grid is creating jobs now, as workers are hired to install it. However, a few years down the road it will be a jobs destroyer, exactly as Brooks says, since workers will no longer be needed to read meters.

Okay, what’s the problem? Right now we have an excess supply of labor. We need things for people to do to give them jobs. Installing the Smart Grid does that. However, we expect to be back at full employment at some point in the future. At that point, we will value efficiency. If we don’t have to send tens of thousands of people around to read meters then they will be available to do other productive work. (Remember the retirement of the baby boomers and the shortage of workers this creates? Efficiency is a good thing.)

Being serious about this story, green jobs were in a fact a relatively small part of the stimulus. Recovery.gov shows $9 billion going to the main environmental program. There was also roughly the same amount used for energy-related tax incentives. If we say that a total of $20 billion went to green projects either through direct spending or tax incentives and we assume an average of cost of $200,000 per job, then we should expect to see 100,000 green jobs.

It’s not easy to determine whether we got these jobs or not. These are construction workers who are installing energy efficient windows, the workers in the factories that produce not just the windows, but the materials that go into the windows, the truck drivers who transport the material and the windows, and the sales clerks who take the orders and do the billing at every company involved in the process.

It is also important to remember that we are in a downturn where the economy is operating below full employment. That means that we are wasting resources by not spending money. Money that is spent inefficiently, but puts people to work, is better than just leaving workers idle. If there are more efficient ways to spend the money, then that is even better, but Brooks didn’t give us his list.

Green jobs will not be a panacea that will fix an otherwise sick economy. If we want manufacturing jobs (green or otherwise) then we have to bring down the over-valued dollar. If we allow a parasitic financial sector to persist then it will be a drain on the economy no matter how green it is. But there is no reason to think that energy-saving industries will be any less effective in generating employment rather than energy-using industries.

David Brooks told readers today that there are no jobs in the green economy. While many political figures may have oversold the prospect for green jobs, the case that Brooks musters is much less clear than he suggests. For example, he tells us that:

“California was awarded $186 million in federal stimulus money to weatherize homes. So far, the program has created the equivalent of only 538 full-time jobs.”

While that may sound like a pretty bad spending to jobs ratio, if we go to the article that Brooks references, we see that the main problem is that only a bit more than half of the money has been spent. If we say that $100 million has been spent to get us 238 jobs, that translates into $186,000 a job. That’s not great, but if we had the same ratio for the whole stimulus (counting the AMT) then it would translate into 4.2 million jobs. Given that this money comes at essentially zero cost right now (the real interest rate on government debt is negative), this doesn’t seem like too bad a way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

He then tells us that:

“executives at Johnson Controls turned $300 million in green technology grants into 150 jobs — that’s $2 million per job.”

Okay, this is big-time sloppy. Most of the jobs created when people buy a GM car are not at General Motors. Most of the jobs created when people buy an iPad are not at Apple. If Brooks wants to find out how many jobs were created by this $300 million in green technology grants he will have to go beyond the executives at Johnson Controls and talk to suppliers. Who knows what this will uncover (they may all be in China), but the fact that Johnson Controls did not create many jobs really doesn’t tell us anything.

However, the best story in Brooks’ arsenal is his complaint about the Smart Grids Initiative. Based on a story from the Washington Post, he tells us that:

“the Smart Grid, while efficient and environmentally beneficial, will be a net job destroyer. For example, 28,000 meter-reading jobs will be replaced by the Smart Grid’s automatic transmitters.”

If we turn to the piece, we see that the Smart Grid is creating jobs now, as workers are hired to install it. However, a few years down the road it will be a jobs destroyer, exactly as Brooks says, since workers will no longer be needed to read meters.

Okay, what’s the problem? Right now we have an excess supply of labor. We need things for people to do to give them jobs. Installing the Smart Grid does that. However, we expect to be back at full employment at some point in the future. At that point, we will value efficiency. If we don’t have to send tens of thousands of people around to read meters then they will be available to do other productive work. (Remember the retirement of the baby boomers and the shortage of workers this creates? Efficiency is a good thing.)

Being serious about this story, green jobs were in a fact a relatively small part of the stimulus. Recovery.gov shows $9 billion going to the main environmental program. There was also roughly the same amount used for energy-related tax incentives. If we say that a total of $20 billion went to green projects either through direct spending or tax incentives and we assume an average of cost of $200,000 per job, then we should expect to see 100,000 green jobs.

It’s not easy to determine whether we got these jobs or not. These are construction workers who are installing energy efficient windows, the workers in the factories that produce not just the windows, but the materials that go into the windows, the truck drivers who transport the material and the windows, and the sales clerks who take the orders and do the billing at every company involved in the process.

It is also important to remember that we are in a downturn where the economy is operating below full employment. That means that we are wasting resources by not spending money. Money that is spent inefficiently, but puts people to work, is better than just leaving workers idle. If there are more efficient ways to spend the money, then that is even better, but Brooks didn’t give us his list.

Green jobs will not be a panacea that will fix an otherwise sick economy. If we want manufacturing jobs (green or otherwise) then we have to bring down the over-valued dollar. If we allow a parasitic financial sector to persist then it will be a drain on the economy no matter how green it is. But there is no reason to think that energy-saving industries will be any less effective in generating employment rather than energy-using industries.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post used a front page story to scare readers about public sector pensions, implying that they faced an enormous unfunded liability. It refers to “states facing, by one estimate, a combined $3 trillion in unfunded pension liabilities.”

It is unlikely that readers are able to assess the meaning of this $3 trillion figure in any meaningful way. It is worth noting first that it assumes that the stock market will provide a return that is approximately half of its historic average over the next three decades. If the economy and profits grow as projected, it would be necessary for stock prices to fall so much that they would have to be negative before the end of the 30-year period over which pensions are typically evaluated.

If we take the more typical figure of $1 trillion and compare it to future GDP, it is equal to approximately 0.2 percent of projected GDP over the 30 year planning period. By comparison, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have added approximately 1.6 percentage points of GDP to the military budget. This means that the unfunded liability of state and local pensions is approximately one eighth as large as the costs of these wars. This sort of context might have been helpful to readers.

In reporting the size of Rhode Island’s pensions it would have been helpful to remind readers that many of these workers do not collect Social Security. That means their pensions are often their entire retirement income.

The Washington Post used a front page story to scare readers about public sector pensions, implying that they faced an enormous unfunded liability. It refers to “states facing, by one estimate, a combined $3 trillion in unfunded pension liabilities.”

It is unlikely that readers are able to assess the meaning of this $3 trillion figure in any meaningful way. It is worth noting first that it assumes that the stock market will provide a return that is approximately half of its historic average over the next three decades. If the economy and profits grow as projected, it would be necessary for stock prices to fall so much that they would have to be negative before the end of the 30-year period over which pensions are typically evaluated.

If we take the more typical figure of $1 trillion and compare it to future GDP, it is equal to approximately 0.2 percent of projected GDP over the 30 year planning period. By comparison, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have added approximately 1.6 percentage points of GDP to the military budget. This means that the unfunded liability of state and local pensions is approximately one eighth as large as the costs of these wars. This sort of context might have been helpful to readers.

In reporting the size of Rhode Island’s pensions it would have been helpful to remind readers that many of these workers do not collect Social Security. That means their pensions are often their entire retirement income.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Arghh!!!!!!!! Don’t you have to know anything to write for a major newspaper these days? USA Today told readers that:

“That raise actually might not be as good as it looks. The extra money is nice, but it could very well bump you into the next tax bracket, possibly leaving you with less money than you had before the raise.”

No, no and 286,000 times no! The tax system brackets give marginal rates. This means that if the raise bumps you into a higher bracket then you pay more taxes only on the income in the higher bracket. Suppose that the tax bracket for income under $200k is 25 percent, and for income over $200k is 33 percent. If you get a raise that pushes your income from $195,000 to $205,000 then you only pay the higher 33 percent tax rate on the $5,000 that is above the $200k threshold not your whole income. Therefore, there is no (as in none, nada, not any) way that getting more money, and being pushed into a higher tax bracket will leave you with less money after taxes.

Don’t the writers and editors at USA Today know this?

Arghh!!!!!!!! Don’t you have to know anything to write for a major newspaper these days? USA Today told readers that:

“That raise actually might not be as good as it looks. The extra money is nice, but it could very well bump you into the next tax bracket, possibly leaving you with less money than you had before the raise.”

No, no and 286,000 times no! The tax system brackets give marginal rates. This means that if the raise bumps you into a higher bracket then you pay more taxes only on the income in the higher bracket. Suppose that the tax bracket for income under $200k is 25 percent, and for income over $200k is 33 percent. If you get a raise that pushes your income from $195,000 to $205,000 then you only pay the higher 33 percent tax rate on the $5,000 that is above the $200k threshold not your whole income. Therefore, there is no (as in none, nada, not any) way that getting more money, and being pushed into a higher tax bracket will leave you with less money after taxes.

Don’t the writers and editors at USA Today know this?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Neil Irwin at the Post did some real reporting today. He talked to business executives and reviewed conference calls to determine if there was evidence that they were scaling back their expansion plans. Irwin found considerable nervousness, but little evidence that businesses planned to curtain investment and hiring. This supports the view that the economy’s near-term prospects are for a continuation of weak growth, but no double-dip. Of course the current growth rate is not rapid enough to even keep pace with the growth of the labor force, much less bring down the unemployment rate, so this is not exactly good news.

The piece does error in saying that the Fed is out of ammunition. The Fed could take more extreme measures such as targeting a 1.0 percent interest rate for 5-year Treasury bonds or even targeting a higher rate of inflation, as Bernanke had advocated for Japan back when he was still a professor at Princeton. There are serious political obstacles to the Fed adopting such policies, however it is wrong to imply that it does not have options that could provide a stronger boost the economy.

Neil Irwin at the Post did some real reporting today. He talked to business executives and reviewed conference calls to determine if there was evidence that they were scaling back their expansion plans. Irwin found considerable nervousness, but little evidence that businesses planned to curtain investment and hiring. This supports the view that the economy’s near-term prospects are for a continuation of weak growth, but no double-dip. Of course the current growth rate is not rapid enough to even keep pace with the growth of the labor force, much less bring down the unemployment rate, so this is not exactly good news.

The piece does error in saying that the Fed is out of ammunition. The Fed could take more extreme measures such as targeting a 1.0 percent interest rate for 5-year Treasury bonds or even targeting a higher rate of inflation, as Bernanke had advocated for Japan back when he was still a professor at Princeton. There are serious political obstacles to the Fed adopting such policies, however it is wrong to imply that it does not have options that could provide a stronger boost the economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article discussing jobs and the environment today. It told readers about research by Michael Greenstone, an economics professor at M.I.T, that found that the Clean Air Act and amendments from 1972-1987 led to a loss of 600,000-700,000 in the industries directly.

It is important to note that this is not a measure of the job loss to the economy as a whole. Money that was not spent in these industries was mostly spent elsewhere. This means that the job loss to the economy as a whole from these regulations would have been a small fraction of this number.

In fact, since these regulations have been shown to have large health benefits, it is very possible that they increased jobs for the economy as a whole. If people are on average more healthy, then health insurance will cost less. This will increase real wages and lead to more jobs.

The NYT had an article discussing jobs and the environment today. It told readers about research by Michael Greenstone, an economics professor at M.I.T, that found that the Clean Air Act and amendments from 1972-1987 led to a loss of 600,000-700,000 in the industries directly.

It is important to note that this is not a measure of the job loss to the economy as a whole. Money that was not spent in these industries was mostly spent elsewhere. This means that the job loss to the economy as a whole from these regulations would have been a small fraction of this number.

In fact, since these regulations have been shown to have large health benefits, it is very possible that they increased jobs for the economy as a whole. If people are on average more healthy, then health insurance will cost less. This will increase real wages and lead to more jobs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Just after I say something nice about the WAPO’s reporting, the paper does its best to make up for its good deed. We find the Post trying to blame the slow recovery on demographics. See, the big problem is that because of the retirement of the baby boomers the labor market isn’t growing as fast as it had in prior recoveries.

Okay, let’s get this one straight. We have more than 25 million people unemployed, underemployed, or out of the workforce altogether because they have given up looking for a job. And, the problem is that the labor force isn’t growing fast enough?

How does that work? Suppose the labor force had grown by another 1 percentage point in each of the last four years. Why wouldn’t that just mean that we have another 6 million people looking for jobs?

There is an argument that slower labor force growth will lead to slower GDP growth over the long-run. This is almost certainly true, but it still could mean more rapid per capita GDP growth, in which case it is difficult to see the problem. But, this is a long-run story where we assume that resources, most importantly labor, is fully utilized. This argument makes zero sense in an economy with large amounts of unemployment and idle resources like the one we have now.

Just after I say something nice about the WAPO’s reporting, the paper does its best to make up for its good deed. We find the Post trying to blame the slow recovery on demographics. See, the big problem is that because of the retirement of the baby boomers the labor market isn’t growing as fast as it had in prior recoveries.

Okay, let’s get this one straight. We have more than 25 million people unemployed, underemployed, or out of the workforce altogether because they have given up looking for a job. And, the problem is that the labor force isn’t growing fast enough?

How does that work? Suppose the labor force had grown by another 1 percentage point in each of the last four years. Why wouldn’t that just mean that we have another 6 million people looking for jobs?

There is an argument that slower labor force growth will lead to slower GDP growth over the long-run. This is almost certainly true, but it still could mean more rapid per capita GDP growth, in which case it is difficult to see the problem. But, this is a long-run story where we assume that resources, most importantly labor, is fully utilized. This argument makes zero sense in an economy with large amounts of unemployment and idle resources like the one we have now.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

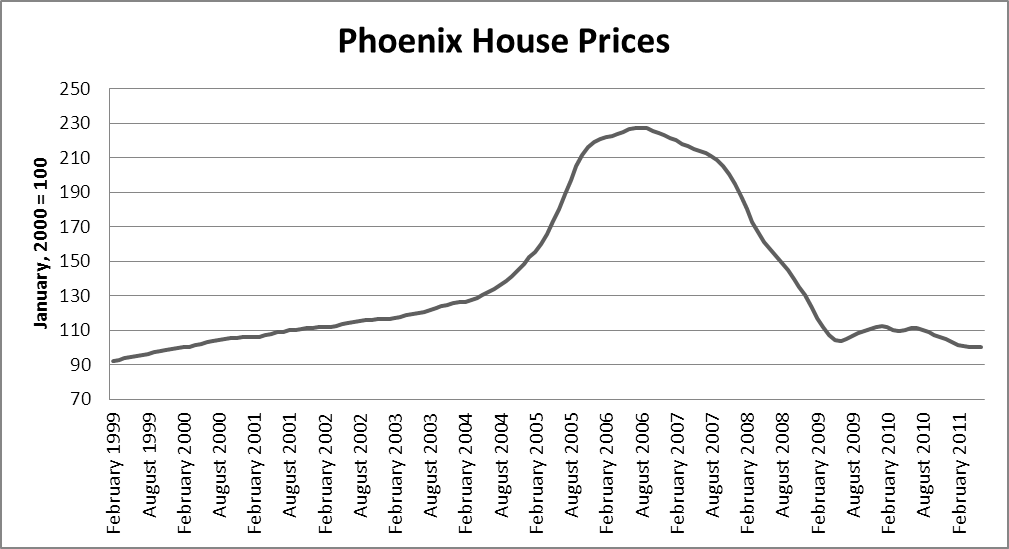

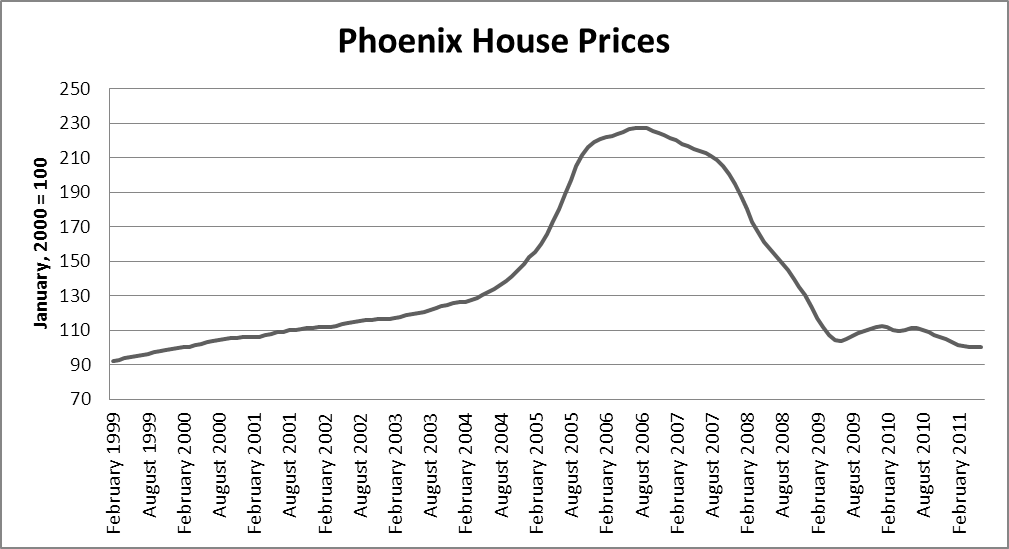

Ryan Avent criticizes the building restrictions in California’s coastal cities in arguing for the benefit of increased population density in cities. He contrasts the high house prices in cities like San Francisco and San Jose with Phoenix, which has few restrictions on building.

Phoenix may not be an ideal city for such a comparison. It was one of the cities that was most caught up in the bubble. Five years ago there would not have been anywhere as near as large a difference between house prices in the coastal cities and Phoenix.

Source: Case-Shiller 20 City Index.

It is not clear that the pattern in Phoenix’s housing market is one that many cities would want to emulate.

Ryan Avent criticizes the building restrictions in California’s coastal cities in arguing for the benefit of increased population density in cities. He contrasts the high house prices in cities like San Francisco and San Jose with Phoenix, which has few restrictions on building.

Phoenix may not be an ideal city for such a comparison. It was one of the cities that was most caught up in the bubble. Five years ago there would not have been anywhere as near as large a difference between house prices in the coastal cities and Phoenix.

Source: Case-Shiller 20 City Index.

It is not clear that the pattern in Phoenix’s housing market is one that many cities would want to emulate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión