The NYT had an article on budget negotiations in which it implied a false symmetry on key issues in the debate:

“On Thursday, the leaders grappled with the most difficult issues politically for each party: cuts to and , entitlement programs long defended by Democrats; and new revenues from the tax code, anathema to Republicans, who say they will not vote for anything resembling a tax increase.”

This symmetry is misplaced because the Democrats’ base actually wants to see the rich pay more in taxes. By contrast, the Republicans’ base actually strongly supports Medicare and to a lesser extent Medicaid. The Democrats need the Republicans to get a tax increase passed through Congress. The Republicans need the Democrats to give them cover for cuts that are unpopular across the board.

The NYT had an article on budget negotiations in which it implied a false symmetry on key issues in the debate:

“On Thursday, the leaders grappled with the most difficult issues politically for each party: cuts to and , entitlement programs long defended by Democrats; and new revenues from the tax code, anathema to Republicans, who say they will not vote for anything resembling a tax increase.”

This symmetry is misplaced because the Democrats’ base actually wants to see the rich pay more in taxes. By contrast, the Republicans’ base actually strongly supports Medicare and to a lesser extent Medicaid. The Democrats need the Republicans to get a tax increase passed through Congress. The Republicans need the Democrats to give them cover for cuts that are unpopular across the board.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Forgiveness is wonderful, but forgetfulness has no place in policy debates. The idea that the Moody’s and Standard and Poors should be seen as impartial arbiters of the creditworthiness of the U.S. government, whose integrity and judgement is beyond question, does not pass the laugh test.

Their warnings over possible debt downgrades associated with delays in raising the debt ceiling may be made in good faith. Certainly the failure to raise the ceiling by August 2 would be very bad news for the creditworthiness of U.S. debt. But, their recent history suggests that any statement from these companies must be viewed with a bit of skepticism.

It is also worth noting that the markets have often not agreed with the rating agencies’ assessments. Both have downgraded Japan’s debt, yet the country can still sell 10-year bonds at interest rates of less than 1.5 percent.

Forgiveness is wonderful, but forgetfulness has no place in policy debates. The idea that the Moody’s and Standard and Poors should be seen as impartial arbiters of the creditworthiness of the U.S. government, whose integrity and judgement is beyond question, does not pass the laugh test.

Their warnings over possible debt downgrades associated with delays in raising the debt ceiling may be made in good faith. Certainly the failure to raise the ceiling by August 2 would be very bad news for the creditworthiness of U.S. debt. But, their recent history suggests that any statement from these companies must be viewed with a bit of skepticism.

It is also worth noting that the markets have often not agreed with the rating agencies’ assessments. Both have downgraded Japan’s debt, yet the country can still sell 10-year bonds at interest rates of less than 1.5 percent.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Who could blame him? After all, it is hard to get news in Washington, D.C. Yes, yet again someone has referred to a deficit commission report that does not exist. Krauthammer is referring to the report of the commission’s co-chairs, Morgan Stanley director Erskine Bowles and former Wyoming senator Alan Simpson. The commission did not vote on this package by the President’s deadline and the co-chairs report would not have gotten the necessary majority in any case. Therefore there is no commission report. This one shouldn’t be hard, even for people who write columns for the Washington Post.

Who could blame him? After all, it is hard to get news in Washington, D.C. Yes, yet again someone has referred to a deficit commission report that does not exist. Krauthammer is referring to the report of the commission’s co-chairs, Morgan Stanley director Erskine Bowles and former Wyoming senator Alan Simpson. The commission did not vote on this package by the President’s deadline and the co-chairs report would not have gotten the necessary majority in any case. Therefore there is no commission report. This one shouldn’t be hard, even for people who write columns for the Washington Post.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Glenn Kessler, the Post’s Fact Checker, did a nice job trying to pin down the law on whether Social Security benefits can still be paid once we have hit the debt ceiling. This is a tough one because payment of benefits would draw down the trust fund, which is part of the $14.3 trillion debt, dollar for dollar. This means that they would not add to the debt and push the government over the ceiling. Still, it is not entirely clear that the payments would be kosher.

Glenn Kessler, the Post’s Fact Checker, did a nice job trying to pin down the law on whether Social Security benefits can still be paid once we have hit the debt ceiling. This is a tough one because payment of benefits would draw down the trust fund, which is part of the $14.3 trillion debt, dollar for dollar. This means that they would not add to the debt and push the government over the ceiling. Still, it is not entirely clear that the payments would be kosher.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Nicholas Kristof is mostly on the mark in his column this morning, but he does repeat the Clinton fiscal responsibility balanced the budget myth. This is not true.

An examination of the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projections from the 1990s shows that in 1996 CBO still projected a deficit of 2.7 percent of GDP for fiscal year 2000. Instead, we had a surplus of 2.4 percent of GDP, a shift of 5.1 percentage points of GDP (@$750 billion in today’s economy).

This shift did not come about from tax increases or spending cuts. CBO estimates that the tax and spending changes between 1996 and 2000 added $10 billion to the year 2000 deficit. The shift was entirely attributable to faster than expected economic growth and especially the decision by Federal Reserve Board chairman to allow the unemployment rate to fall to 4.0 percent.

CBO had projected an unemployment rate of 6.0 percent for 2000. This was the conventional estimate of the NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment) at the time. It was only because Greenspan ignored this nearly universally held view in the economics profession (and the Clinton appointees to the Fed) that the economy was able to grow enough to get the unemployment rate down to 4.0 percent and to bring the budget from deficit to surplus.

This is an important piece of history that is routinely buried.

Nicholas Kristof is mostly on the mark in his column this morning, but he does repeat the Clinton fiscal responsibility balanced the budget myth. This is not true.

An examination of the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projections from the 1990s shows that in 1996 CBO still projected a deficit of 2.7 percent of GDP for fiscal year 2000. Instead, we had a surplus of 2.4 percent of GDP, a shift of 5.1 percentage points of GDP (@$750 billion in today’s economy).

This shift did not come about from tax increases or spending cuts. CBO estimates that the tax and spending changes between 1996 and 2000 added $10 billion to the year 2000 deficit. The shift was entirely attributable to faster than expected economic growth and especially the decision by Federal Reserve Board chairman to allow the unemployment rate to fall to 4.0 percent.

CBO had projected an unemployment rate of 6.0 percent for 2000. This was the conventional estimate of the NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment) at the time. It was only because Greenspan ignored this nearly universally held view in the economics profession (and the Clinton appointees to the Fed) that the economy was able to grow enough to get the unemployment rate down to 4.0 percent and to bring the budget from deficit to surplus.

This is an important piece of history that is routinely buried.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, the United States has officially been asking (demanding?, begging?) China to raise the value of its currency against the dollar. Yet, the media continually threaten the country with the story that China may sour on the U.S. and stop buying U.S. debt if we don’t get our budget deficit down.

However, if China stopped buying U.S. debt it would lead to a rise of the yuan against the dollar. This is exactly what the Obama administration has ostensibly been asking them to do.

In other words, China has no leverage in this picture. Their implicit threat is to do exactly what we supposedly want them to do. So why is the media trying to scare us?

Yes, the United States has officially been asking (demanding?, begging?) China to raise the value of its currency against the dollar. Yet, the media continually threaten the country with the story that China may sour on the U.S. and stop buying U.S. debt if we don’t get our budget deficit down.

However, if China stopped buying U.S. debt it would lead to a rise of the yuan against the dollar. This is exactly what the Obama administration has ostensibly been asking them to do.

In other words, China has no leverage in this picture. Their implicit threat is to do exactly what we supposedly want them to do. So why is the media trying to scare us?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what readers of the NYT’s box on “issues holding up debt ceiling agreement” would conclude. The box tells readers that:

“Officials have said that the program, which provides health care to people 65 and older, is not sustainable in its current form.”

This is not true. There is no, as in zero, none, official document that says the program is not sustainable in its current form. There are official documents that show the program will need additional revenue at some point. The ACA passed by Congress last year reduced the projected shortfall in the program by more than 75 percent.

As it stands, the projected shortfall over the program’s 75-year planning horizon is less than 0.4 percent of GDP. This is less than one quarter of the cost of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

That’s what readers of the NYT’s box on “issues holding up debt ceiling agreement” would conclude. The box tells readers that:

“Officials have said that the program, which provides health care to people 65 and older, is not sustainable in its current form.”

This is not true. There is no, as in zero, none, official document that says the program is not sustainable in its current form. There are official documents that show the program will need additional revenue at some point. The ACA passed by Congress last year reduced the projected shortfall in the program by more than 75 percent.

As it stands, the projected shortfall over the program’s 75-year planning horizon is less than 0.4 percent of GDP. This is less than one quarter of the cost of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Amazon is known throughout the world as one of the most innovative tax cheats anywhere. It makes its profit largely by allowing customers to avoid state sales taxes and sharing the savings. States are now taking steps to crack down on this scam, requiring Internet retailers with any ties to in-state businesses to start collecting taxes on their sales in the state. California took this route this month.

The NYT had an article highlighting Amazon’s efforts to fight back to protect its loophole, which includes a plan to place an initiative on California’s ballot. In laying out Amazon’s argument, the piece includes an unanswered argument from Amazon, that the law places a huge burden on small Internet retailers by requiring them to collect taxes in hundreds of different jurisdictions.

The piece should have reminded readers that there are services that will handle the tax collection for smaller businesses for a modest fee. These services are comparable to the payroll companies that small businesses often rely upon to get tax and benefit payments handled correctly.

Amazon has a history of putting out absurd arguments to protect its tax loophole. It had previously argued that it lacked the technical competence to keep track of the different tax provisions in all the jurisdictions where it sold products. This argument was contradicted by the fact that retailers like Wal-Mart and Target seem to have relatively little problem getting tax collections mostly right. Presumably, the programmers at the these traditional brick and mortar retailers are not that much more competent than the crew at Amazon.

Given Amazon’s history, the NYT should not present its claims to readers without including a response.

Amazon is known throughout the world as one of the most innovative tax cheats anywhere. It makes its profit largely by allowing customers to avoid state sales taxes and sharing the savings. States are now taking steps to crack down on this scam, requiring Internet retailers with any ties to in-state businesses to start collecting taxes on their sales in the state. California took this route this month.

The NYT had an article highlighting Amazon’s efforts to fight back to protect its loophole, which includes a plan to place an initiative on California’s ballot. In laying out Amazon’s argument, the piece includes an unanswered argument from Amazon, that the law places a huge burden on small Internet retailers by requiring them to collect taxes in hundreds of different jurisdictions.

The piece should have reminded readers that there are services that will handle the tax collection for smaller businesses for a modest fee. These services are comparable to the payroll companies that small businesses often rely upon to get tax and benefit payments handled correctly.

Amazon has a history of putting out absurd arguments to protect its tax loophole. It had previously argued that it lacked the technical competence to keep track of the different tax provisions in all the jurisdictions where it sold products. This argument was contradicted by the fact that retailers like Wal-Mart and Target seem to have relatively little problem getting tax collections mostly right. Presumably, the programmers at the these traditional brick and mortar retailers are not that much more competent than the crew at Amazon.

Given Amazon’s history, the NYT should not present its claims to readers without including a response.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post, which regularly uses both its editorial and news pages to push for budget cuts, has a front page article today that warns the United States could end up like Greece. The article includes a quote from University of Maryland economist Peter Morici, telling readers that:

“If Congress raises the debt ceiling without a long-term plan for reducing the federal deficit, he added, ‘they’ll never solve the problem, and we’ll end up like Greece.'”

It would have been worth pointing out that the United States cannot end up like Greece because the United States, unlike Greece, has its own currency. Greece is like the state of Ohio. If it has a shortfall it has to borrow in financial markets. Ohio can appeal to the federal government for assistance, just as Greece can turn to the EU, the ECB, and the IMF, but both have to accept whatever terms these bodies impose as a condition for their support.

By contrast, the U.S. government is always free to buy up debt issued in its own currency through the Fed. In principle, this could lead to a problem of inflation, however the economy is very far from reaching this point with a vast amount of unemployed labor and under-utilized capacity.

Of course, the U.S. government also has no difficulty whatsoever borrowing in financial markets. It is currently able to sell long-term debt at interest rates just over 3 percent. This means that the people investing trillions of dollars in these markets do not share Mr. Morici’s assessment of the fiscal situation of the U.S. government.

It would have been worth presenting the views of someone who could tell the difference between the United States and Greece in this article.

The Washington Post, which regularly uses both its editorial and news pages to push for budget cuts, has a front page article today that warns the United States could end up like Greece. The article includes a quote from University of Maryland economist Peter Morici, telling readers that:

“If Congress raises the debt ceiling without a long-term plan for reducing the federal deficit, he added, ‘they’ll never solve the problem, and we’ll end up like Greece.'”

It would have been worth pointing out that the United States cannot end up like Greece because the United States, unlike Greece, has its own currency. Greece is like the state of Ohio. If it has a shortfall it has to borrow in financial markets. Ohio can appeal to the federal government for assistance, just as Greece can turn to the EU, the ECB, and the IMF, but both have to accept whatever terms these bodies impose as a condition for their support.

By contrast, the U.S. government is always free to buy up debt issued in its own currency through the Fed. In principle, this could lead to a problem of inflation, however the economy is very far from reaching this point with a vast amount of unemployed labor and under-utilized capacity.

Of course, the U.S. government also has no difficulty whatsoever borrowing in financial markets. It is currently able to sell long-term debt at interest rates just over 3 percent. This means that the people investing trillions of dollars in these markets do not share Mr. Morici’s assessment of the fiscal situation of the U.S. government.

It would have been worth presenting the views of someone who could tell the difference between the United States and Greece in this article.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

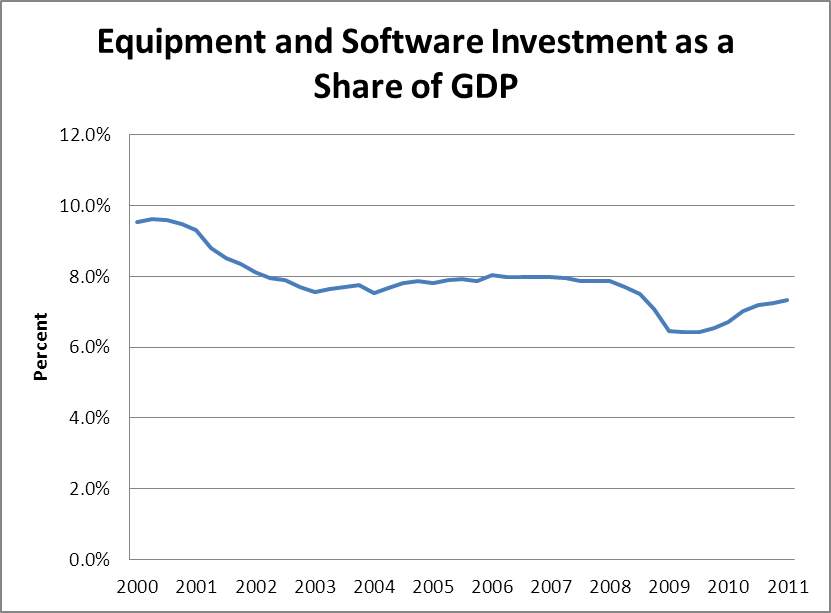

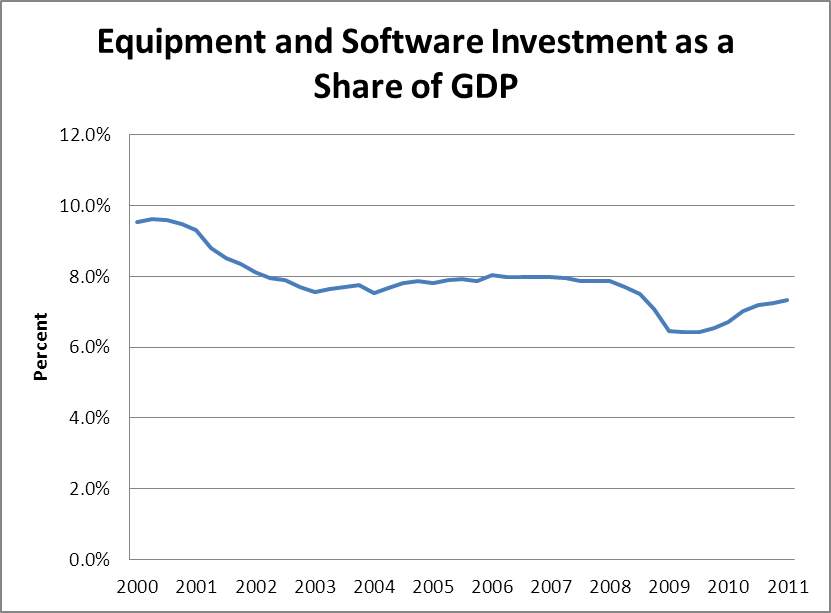

Morning Edition spread a bit of nonsense this morning in a segment on innovation. It told listeners that firms are not investing much right now, which it attributed to uncertainty. It’s not clear what metric it is using, but investment in equipment and software as a share of GDP is almost back to its pre-recession peak. Given that many sectors on the economy are still operating far below full capacity, this is a fairly high level of investment.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The segment also included the unsupported assertion that Americans used to be the most innovative people in the world, but this is no longer true. It does not give its measure of innovation. The United States trailed most other wealthy countries in productivity growth in the years prior to 1995. Since then, productivity growth has been somewhat more rapid in the U.S. than in other countries, but this reverses the pattern identified in the story. Other countries have more small businesses and self-employed people relative to the size of their workforce, at least in part because they have national health insurance. (Entrepreneurs know that they will still have health care even if their business fails.) It is not clear what measure produces the pattern of innovation described in the segment.

Morning Edition spread a bit of nonsense this morning in a segment on innovation. It told listeners that firms are not investing much right now, which it attributed to uncertainty. It’s not clear what metric it is using, but investment in equipment and software as a share of GDP is almost back to its pre-recession peak. Given that many sectors on the economy are still operating far below full capacity, this is a fairly high level of investment.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The segment also included the unsupported assertion that Americans used to be the most innovative people in the world, but this is no longer true. It does not give its measure of innovation. The United States trailed most other wealthy countries in productivity growth in the years prior to 1995. Since then, productivity growth has been somewhat more rapid in the U.S. than in other countries, but this reverses the pattern identified in the story. Other countries have more small businesses and self-employed people relative to the size of their workforce, at least in part because they have national health insurance. (Entrepreneurs know that they will still have health care even if their business fails.) It is not clear what measure produces the pattern of innovation described in the segment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión