Actually, what NPR did not mention was the value of the dollar, however an over-valued dollar has the same effect on U.S. exports as a tax on exports. In other words, if the dollar is 15 percent over-valued, this is equivalent to imposing a 15 percent tax on all the goods exported from the country, since it makes our goods roughly 15 percent more expensive to people living in other countries. Similarly, if the dollar is over-valued by 15 percent then it is equivalent to subsidizing imports by 15 percent.

When the United States has imposed tariffs of this magnitude on imports, for example President Bush’s temporary tax on imported steel in 2001, it has received a huge amount of attention from the media. It is therefore remarkable that a piece devoted to the prospects of manufacturing never mentions the dollar and the likelihood that it is substantially over-valued.

This piece also points to productivity growth as one of the main factors contributing to the reduction in the share of employment in manufacturing. It is important to realize that productivity growth in manufacturing would only lead to a reduced employment share insofar as it has exceeded the rate of productivity growth elsewhere in the economy.

This has in fact been the case. But the gap between productivity growth in manufacturing and the rest of the economy would explain a much smaller drop in the manufacturing share of total employment than the absolute level of productivity growth. Much more of the drop in the manufacturing share of employment is attributable to import competition and the trade deficit. If the U.S. had balanced trade, it would increase manufacturing employment by more than 40 percent, creating more than 4 million new jobs in manufacturing.

Actually, what NPR did not mention was the value of the dollar, however an over-valued dollar has the same effect on U.S. exports as a tax on exports. In other words, if the dollar is 15 percent over-valued, this is equivalent to imposing a 15 percent tax on all the goods exported from the country, since it makes our goods roughly 15 percent more expensive to people living in other countries. Similarly, if the dollar is over-valued by 15 percent then it is equivalent to subsidizing imports by 15 percent.

When the United States has imposed tariffs of this magnitude on imports, for example President Bush’s temporary tax on imported steel in 2001, it has received a huge amount of attention from the media. It is therefore remarkable that a piece devoted to the prospects of manufacturing never mentions the dollar and the likelihood that it is substantially over-valued.

This piece also points to productivity growth as one of the main factors contributing to the reduction in the share of employment in manufacturing. It is important to realize that productivity growth in manufacturing would only lead to a reduced employment share insofar as it has exceeded the rate of productivity growth elsewhere in the economy.

This has in fact been the case. But the gap between productivity growth in manufacturing and the rest of the economy would explain a much smaller drop in the manufacturing share of total employment than the absolute level of productivity growth. Much more of the drop in the manufacturing share of employment is attributable to import competition and the trade deficit. If the U.S. had balanced trade, it would increase manufacturing employment by more than 40 percent, creating more than 4 million new jobs in manufacturing.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is remarkable how the Washington Post (a.k.a. Fox on 15th) cannot write a story on the budget deficit without feeling the need to editorialize. Today’s piece referred to the “the swollen national debt.”

Real newspapers would have just called it “the national debt.” However, the Post could not resist the opportunity to push their editorial line pushing the need for deficit reduction.

It is remarkable how the Washington Post (a.k.a. Fox on 15th) cannot write a story on the budget deficit without feeling the need to editorialize. Today’s piece referred to the “the swollen national debt.”

Real newspapers would have just called it “the national debt.” However, the Post could not resist the opportunity to push their editorial line pushing the need for deficit reduction.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I always enjoy reading Ezra Klein’s blog. He’s an excellent writer and he does his homework. However, he really missed the story in his review of Inside Job (even though I do appreciate the favorable mention).

Ezra criticizes the movie for making the story one of corrupt economists blessing the evil doers of Wall Street:

“What’s remarkable about the financial crisis isn’t just how many people got it wrong, but how many people who got it wrong had an incentive to get it right. Journalists. Hedge funds. Independent investors. Academics. Regulators. Even traders, many of whom had most of their money tied up in their soon-to-be-worthless firms.”

This is the right point, but I think Ezra takes it in the wrong direction. Certainly all of these people were not on the take in the same way as some of the film’s heroes (i.e. former Federal Reserve Board Governor Frederick Mishkin who got paid six figures to write a report praising Iceland to the sky in 2006). However, it does not follow that they had incentive to “get it right.”

Getting it right meant that you had to say that the honchos were wrong. You had to say that Martin Feldstein, Gregory Mankiw, Larry Summers, Alan Blinder, Ben Bernanke, and the Maestro, Alan Greenspan, were missing the largest asset bubble in the history of the world right in front of their eyes.

This would really put you on the firing line if you were an economist at the Fed, the IMF, or even an academic economist hoping to advance in the field. After all, you could be wrong, in which case you might as well spend the rest of your working career wearing a tin foil hat.

On the other hand, what is the cost of going along? It turns out that economists are a remarkably forgiving lot – not in respect to workers in workers in the United States or retirees in Greece – but certainly when it comes to each other. The mantra “who could have known?” has provided a pretty much blanket amnesty. Next to no one got fired and very few people even missed a scheduled promotion for missing the housing bubble; the collapse of which may wreck the economy for a decade. In fact, even Daniel Mudd and Richard Fuld, the men who bankrupted Fannie Mae and Lehman respectively, have both found their way back into very high-paying jobs in finance.

In short, there is a serious problem here of asymmetric risk. There is no doubt that saying there was a bubble posed serious dangers to the careers of those who stepped outside of the consensus established by the top thinkers in the profession. However, just going along with the mainstream view carried no risk whatsoever. There is no reason to believe that anything about this story has changed in the years since the crisis.

Perhaps Inside Job can be blamed for not fully exploring the subtleties of this process, but it was a movie, not a book, and there is a need to be entertaining as well as informative. So, I can agree that the movie did not fully explain the dynamics that allowed for such a dangerous bubble to grow right under the nose of so many intelligent people, but I think it still got the essentials of the story right.

Like Ezra, I qualify as a nerd. But the movie was not intended to provide the full story to the discerning nerd. It was intended to give the essentials to the masses, and on this score I give it high marks.

I always enjoy reading Ezra Klein’s blog. He’s an excellent writer and he does his homework. However, he really missed the story in his review of Inside Job (even though I do appreciate the favorable mention).

Ezra criticizes the movie for making the story one of corrupt economists blessing the evil doers of Wall Street:

“What’s remarkable about the financial crisis isn’t just how many people got it wrong, but how many people who got it wrong had an incentive to get it right. Journalists. Hedge funds. Independent investors. Academics. Regulators. Even traders, many of whom had most of their money tied up in their soon-to-be-worthless firms.”

This is the right point, but I think Ezra takes it in the wrong direction. Certainly all of these people were not on the take in the same way as some of the film’s heroes (i.e. former Federal Reserve Board Governor Frederick Mishkin who got paid six figures to write a report praising Iceland to the sky in 2006). However, it does not follow that they had incentive to “get it right.”

Getting it right meant that you had to say that the honchos were wrong. You had to say that Martin Feldstein, Gregory Mankiw, Larry Summers, Alan Blinder, Ben Bernanke, and the Maestro, Alan Greenspan, were missing the largest asset bubble in the history of the world right in front of their eyes.

This would really put you on the firing line if you were an economist at the Fed, the IMF, or even an academic economist hoping to advance in the field. After all, you could be wrong, in which case you might as well spend the rest of your working career wearing a tin foil hat.

On the other hand, what is the cost of going along? It turns out that economists are a remarkably forgiving lot – not in respect to workers in workers in the United States or retirees in Greece – but certainly when it comes to each other. The mantra “who could have known?” has provided a pretty much blanket amnesty. Next to no one got fired and very few people even missed a scheduled promotion for missing the housing bubble; the collapse of which may wreck the economy for a decade. In fact, even Daniel Mudd and Richard Fuld, the men who bankrupted Fannie Mae and Lehman respectively, have both found their way back into very high-paying jobs in finance.

In short, there is a serious problem here of asymmetric risk. There is no doubt that saying there was a bubble posed serious dangers to the careers of those who stepped outside of the consensus established by the top thinkers in the profession. However, just going along with the mainstream view carried no risk whatsoever. There is no reason to believe that anything about this story has changed in the years since the crisis.

Perhaps Inside Job can be blamed for not fully exploring the subtleties of this process, but it was a movie, not a book, and there is a need to be entertaining as well as informative. So, I can agree that the movie did not fully explain the dynamics that allowed for such a dangerous bubble to grow right under the nose of so many intelligent people, but I think it still got the essentials of the story right.

Like Ezra, I qualify as a nerd. But the movie was not intended to provide the full story to the discerning nerd. It was intended to give the essentials to the masses, and on this score I give it high marks.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran an AP article on the new long-term budget projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) that began:

“The national debt is on pace to equal the annual size of the economy within a decade, levels that could provoke a European-style crisis unless policymakers take action on the federal deficit, according to a report by the Congressional Budget Office.”

This is not true. The CBO report did not warn of “a European-style crisis.” The reason it did not is that a European style crisis does not make sense in the context of the United States. The United States can never be like Greece or Ireland for the simply reason that we print out own currency.

In the event that we actually ran up against serious constraints in credit markets the United States would have the option to have the Fed buy up its debt. Greece and Ireland do not have this option. This could create a risk of inflation, but there is not the risk of insolvency that euro zone governments face.

The economists at CBO know the difference between the United States and the euro zone countries, which is why they did not make the comparisons attributed to them in this article.

The NYT ran an AP article on the new long-term budget projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) that began:

“The national debt is on pace to equal the annual size of the economy within a decade, levels that could provoke a European-style crisis unless policymakers take action on the federal deficit, according to a report by the Congressional Budget Office.”

This is not true. The CBO report did not warn of “a European-style crisis.” The reason it did not is that a European style crisis does not make sense in the context of the United States. The United States can never be like Greece or Ireland for the simply reason that we print out own currency.

In the event that we actually ran up against serious constraints in credit markets the United States would have the option to have the Fed buy up its debt. Greece and Ireland do not have this option. This could create a risk of inflation, but there is not the risk of insolvency that euro zone governments face.

The economists at CBO know the difference between the United States and the euro zone countries, which is why they did not make the comparisons attributed to them in this article.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In the top of the hour news segment on Morning Edition, NPR told listeners that the Congressional Budget Office warned that the national debt will soon equal the annual size of the economy and this could lead to a European-style crisis. This is not true, see below.

In the top of the hour news segment on Morning Edition, NPR told listeners that the Congressional Budget Office warned that the national debt will soon equal the annual size of the economy and this could lead to a European-style crisis. This is not true, see below.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post piece on the new long-term budget projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) began:

“The national debt will exceed the size of the entire U.S. economy by 2021 — and balloon to nearly 200 percent of GDP within 25 years — without dramatic cuts to federal health and retirement programs or steep tax increases, congressional budget analysts said Wednesday.”

Actually, this is not what the projections showed. The CBO projections showed that if Congress simply followed current law, letting the Bush tax cuts expire, not fixing the alternative minimum tax, and most importantly, allowing the spending caps in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to remain in place, then the debt to GDP ratio will soon stabilize and head downwards.

This is the CBO baseline scenario that is actually shown in the graphic accompanying the article, even though it is never mentioned in the article itself. The article focuses of the “alternative fiscal scenario” constructed by CBO, which assumes that Congress will deviate from the baseline in several important ways that will make the deficit worse. This fact should have been explained to readers.

Instead the confusion is compounded with the assertion:

” If current policies are unchanged and the national debt continues to grow, the U.S. economic output could be as much as 6 percent smaller than current projections by 2025 and as much as 18 percent smaller by 2035.”

It is unlikely that many readers would know that “current policies” includes the assumption that Congress will over-ride the spending caps that it voted into law with the ACA last year. It also would have been worth reminding readers that in 2025 per capita income is projected to be approximately 20 percent higher than it is today, so even with this worst case scenario, people would on average still have considerably higher incomes than they do today. In 2035 the projections show that per capita income would be about 40 percent higher.

The article also refers to President Obama’s fiscal commission and tells readers:

“That commission produced a plan that would limit borrowing to a little over $5 trillion over the next decade.”

This is not true. The commission did not issue a report because it did not have the necessary majority to get a report approved. The report referred to in the article is the report of the commission’s co-chairs, Erskine Bowles and former Senator Alan Simpson.

The Washington Post piece on the new long-term budget projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) began:

“The national debt will exceed the size of the entire U.S. economy by 2021 — and balloon to nearly 200 percent of GDP within 25 years — without dramatic cuts to federal health and retirement programs or steep tax increases, congressional budget analysts said Wednesday.”

Actually, this is not what the projections showed. The CBO projections showed that if Congress simply followed current law, letting the Bush tax cuts expire, not fixing the alternative minimum tax, and most importantly, allowing the spending caps in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to remain in place, then the debt to GDP ratio will soon stabilize and head downwards.

This is the CBO baseline scenario that is actually shown in the graphic accompanying the article, even though it is never mentioned in the article itself. The article focuses of the “alternative fiscal scenario” constructed by CBO, which assumes that Congress will deviate from the baseline in several important ways that will make the deficit worse. This fact should have been explained to readers.

Instead the confusion is compounded with the assertion:

” If current policies are unchanged and the national debt continues to grow, the U.S. economic output could be as much as 6 percent smaller than current projections by 2025 and as much as 18 percent smaller by 2035.”

It is unlikely that many readers would know that “current policies” includes the assumption that Congress will over-ride the spending caps that it voted into law with the ACA last year. It also would have been worth reminding readers that in 2025 per capita income is projected to be approximately 20 percent higher than it is today, so even with this worst case scenario, people would on average still have considerably higher incomes than they do today. In 2035 the projections show that per capita income would be about 40 percent higher.

The article also refers to President Obama’s fiscal commission and tells readers:

“That commission produced a plan that would limit borrowing to a little over $5 trillion over the next decade.”

This is not true. The commission did not issue a report because it did not have the necessary majority to get a report approved. The report referred to in the article is the report of the commission’s co-chairs, Erskine Bowles and former Senator Alan Simpson.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’ve been otherwise occupied so I didn’t get around to beating up this utterly bizarre NYT story that features Argentina as presenting a clear warning to Greece of the dangers of default. Fortunately, Krugman picked up on it on his blog.

The basic point is that Argentina’s economy has done extremely well following its default. It is difficult to see why anyone in Greece would not default in an instant if they thought Greece’s economy would follow the same path as Argentina’s economy has over the last 9 1/2 years.

There are good reasons for thinking that Greece may not be as successful, most importantly that it does not currently have its own currency. But Argentina is a model that countries would likely want to emulate, not avoid.

I’ve been otherwise occupied so I didn’t get around to beating up this utterly bizarre NYT story that features Argentina as presenting a clear warning to Greece of the dangers of default. Fortunately, Krugman picked up on it on his blog.

The basic point is that Argentina’s economy has done extremely well following its default. It is difficult to see why anyone in Greece would not default in an instant if they thought Greece’s economy would follow the same path as Argentina’s economy has over the last 9 1/2 years.

There are good reasons for thinking that Greece may not be as successful, most importantly that it does not currently have its own currency. But Argentina is a model that countries would likely want to emulate, not avoid.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The United States has to cut back spending on the Commerce Department or it will bankrupt the country. Okay, I have no evidence for this and it really doesn’t make any sense. The Commerce Department’s budget is about $10 billion a year, less than 0.3 percent of total spending, but this note is written in the spirit of Thomas Friedman.

Just as Thomas Friedman can tell readers that Social Security and Medicare are bankrupting the country with no evidence, in my blognote I get to blame the Commerce Department. The reality of course is that Social Security is fully funded by its own dedicated tax revenue through the year 2036, meaning the program on net imposes no burden on the government.

Under the law, if nothing is done to increase revenues SS will only pay about 80 percent of scheduled benefits in years after 2036. It is prohibited from spending any money beyond what it collects in taxes. The projected shortfall over the program’s 75-year planning period is equal to 0.6 percent of GDP, about one-third of the increase in annual defense spending between 2000 and 2011. It is difficult to see how a program that can only spend what it takes in from taxes could bankrupt the country, but this is Thomas Friedmanland.

There is more of an issue with run-away Medicare costs, but everyone outside of Thomas Friedmanland knows that this is an issue of run-away health care costs. If the United States paid the same amount per person for our health care as people in Canada, Germany, or any other wealthy country we would be looking at huge budget surpluses, not deficits.

This means that if we fix the U.S. health care system, then there will be no Medicare or budget problem. On the other hand, if we fail to fix the system, health care costs will bankrupt the U.S. economy even if we eliminate Medicare and other public health care programs altogether. People know this outside of Thomas Friedmanland, but in Thomas Friedmanland, you get to just make things up.

The United States has to cut back spending on the Commerce Department or it will bankrupt the country. Okay, I have no evidence for this and it really doesn’t make any sense. The Commerce Department’s budget is about $10 billion a year, less than 0.3 percent of total spending, but this note is written in the spirit of Thomas Friedman.

Just as Thomas Friedman can tell readers that Social Security and Medicare are bankrupting the country with no evidence, in my blognote I get to blame the Commerce Department. The reality of course is that Social Security is fully funded by its own dedicated tax revenue through the year 2036, meaning the program on net imposes no burden on the government.

Under the law, if nothing is done to increase revenues SS will only pay about 80 percent of scheduled benefits in years after 2036. It is prohibited from spending any money beyond what it collects in taxes. The projected shortfall over the program’s 75-year planning period is equal to 0.6 percent of GDP, about one-third of the increase in annual defense spending between 2000 and 2011. It is difficult to see how a program that can only spend what it takes in from taxes could bankrupt the country, but this is Thomas Friedmanland.

There is more of an issue with run-away Medicare costs, but everyone outside of Thomas Friedmanland knows that this is an issue of run-away health care costs. If the United States paid the same amount per person for our health care as people in Canada, Germany, or any other wealthy country we would be looking at huge budget surpluses, not deficits.

This means that if we fix the U.S. health care system, then there will be no Medicare or budget problem. On the other hand, if we fail to fix the system, health care costs will bankrupt the U.S. economy even if we eliminate Medicare and other public health care programs altogether. People know this outside of Thomas Friedmanland, but in Thomas Friedmanland, you get to just make things up.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In discussing the Fed’s QE2 program, the NYT tells us that things are much different today than they were a year ago.

“Last year prices were falling; this year, prices are increasing.”

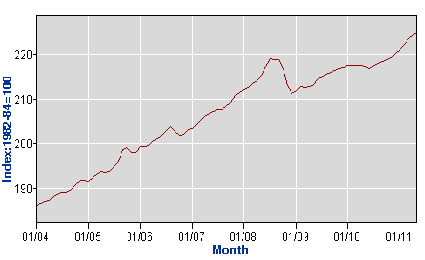

Well, sort of. Here’s the overall CPI where there is in fact a small drop between April and June, although it is completely reversed by the July increase.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

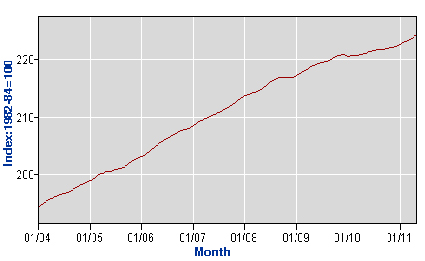

Of course, if we look at the core CPI which the Fed targets, there is no decline in prices at all in the summer of 2010. In fact, inflation looks pretty much exactly the same in the summer of 2011 as it did in the summer of 2010.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In other words, what explains the difference in the Fed’s behavior is not any obvious difference in inflation or even the growth outlook. (Growth projections were if anything stronger in the summer of 2010 than at present.)

Rather, the most obvious explanation is a difference in politics. There is a growing push against any effort to stimulate the economy, which is noted in the article. It is this change in politics that seems to explain the end of quantitative easing, not any change in the economy.

This article includes a peculiar statement by Mark Zandi, of Moody’s Analytics, which attributes the economy’s weakness to a loss of confidence. It would have been useful to ask how he thought low confidence was hurting the economy. Consumer spending continues to be very high relative to income and investment in equipment and software is quite strong given the low capacity utilization rates, so it is not obvious what sector of the economy is being constrained by a lack of confidence.

In discussing the Fed’s QE2 program, the NYT tells us that things are much different today than they were a year ago.

“Last year prices were falling; this year, prices are increasing.”

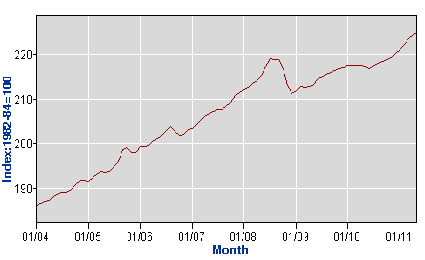

Well, sort of. Here’s the overall CPI where there is in fact a small drop between April and June, although it is completely reversed by the July increase.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

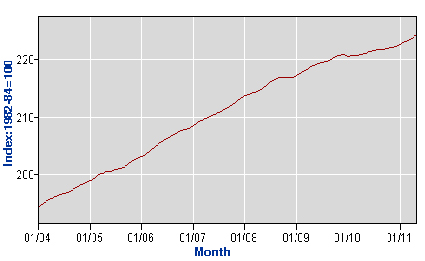

Of course, if we look at the core CPI which the Fed targets, there is no decline in prices at all in the summer of 2010. In fact, inflation looks pretty much exactly the same in the summer of 2011 as it did in the summer of 2010.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In other words, what explains the difference in the Fed’s behavior is not any obvious difference in inflation or even the growth outlook. (Growth projections were if anything stronger in the summer of 2010 than at present.)

Rather, the most obvious explanation is a difference in politics. There is a growing push against any effort to stimulate the economy, which is noted in the article. It is this change in politics that seems to explain the end of quantitative easing, not any change in the economy.

This article includes a peculiar statement by Mark Zandi, of Moody’s Analytics, which attributes the economy’s weakness to a loss of confidence. It would have been useful to ask how he thought low confidence was hurting the economy. Consumer spending continues to be very high relative to income and investment in equipment and software is quite strong given the low capacity utilization rates, so it is not obvious what sector of the economy is being constrained by a lack of confidence.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In its top of the hour news segment NPR told listeners that there is little else that the Fed can do to boost the economy. This is very seriously wrong.

The Fed could do more quantitative easing, it could target a long-term interest rate, for example targeting a 2.5 percent 10-year government bond rate, or it could target a higher inflation rate (e.g. 3-4 percent). All of these measures would some impact in boosting the economy.

The Fed is choosing not to go this route because its open market committee apparently feels the potential benefits do not outweigh the risks, however it is simply wrong to say that additional options to boost the economy do not exist. The Fed has simply opted not to take them.

NPR’s mis-reporting on this point is important because the decisions of the open market committee are in part political ones. They respond to the larger debate within the country. If people do not even know that the Fed has options that could spur growth and reduce unemployment then they will be less likely to try to pressure the Fed to pursue such options.

In its top of the hour news segment NPR told listeners that there is little else that the Fed can do to boost the economy. This is very seriously wrong.

The Fed could do more quantitative easing, it could target a long-term interest rate, for example targeting a 2.5 percent 10-year government bond rate, or it could target a higher inflation rate (e.g. 3-4 percent). All of these measures would some impact in boosting the economy.

The Fed is choosing not to go this route because its open market committee apparently feels the potential benefits do not outweigh the risks, however it is simply wrong to say that additional options to boost the economy do not exist. The Fed has simply opted not to take them.

NPR’s mis-reporting on this point is important because the decisions of the open market committee are in part political ones. They respond to the larger debate within the country. If people do not even know that the Fed has options that could spur growth and reduce unemployment then they will be less likely to try to pressure the Fed to pursue such options.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión