It might have been helpful if the NYT had asked this question instead of just telling readers that:

“But Senate Republicans rolled out their own jobs agenda and took shots at the Obama administration over what they described as undue restrictions on business.

‘This excessive regulation is really seriously inhibiting our effort to get out of this economic recession and create jobs,’ said Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Republican leader.”

Since there have been few important changes in regulation under President Obama it might have been useful to give readers some idea of what the Republicans are talking about. Otherwise, it sounds like they are complaining that Lake Michigan is inhibiting our effort to get out of recession. It could in principle be true — for example if the Lake had enormous floods — but since the Lake has been there a long time, it is not obvious why it would suddenly cause a problem. The same is true for regulation.

It might have been helpful if the NYT had asked this question instead of just telling readers that:

“But Senate Republicans rolled out their own jobs agenda and took shots at the Obama administration over what they described as undue restrictions on business.

‘This excessive regulation is really seriously inhibiting our effort to get out of this economic recession and create jobs,’ said Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Republican leader.”

Since there have been few important changes in regulation under President Obama it might have been useful to give readers some idea of what the Republicans are talking about. Otherwise, it sounds like they are complaining that Lake Michigan is inhibiting our effort to get out of recession. It could in principle be true — for example if the Lake had enormous floods — but since the Lake has been there a long time, it is not obvious why it would suddenly cause a problem. The same is true for regulation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In an article on China’s growing foreign investment the NYT told readers that:

“China is also a major player in the global debt markets, holding about $1.6 trillion in United States Treasury bonds, an investment that helps keep American interest rates low and finances America’s enormous debt.”

It would also be accurate to say that China’s purchase of Treasury bonds “keeps the dollar over-valued and sustains the enormous U.S. trade deficit with China and other countries.”

If China did not purchase these bonds, the dollar would fall against the yuan and other currencies. A lower valued dollar would reduce our imports and increase our exports, moving us closer to balanced trade, increasing U.S. GDP and creating jobs.

In an article on China’s growing foreign investment the NYT told readers that:

“China is also a major player in the global debt markets, holding about $1.6 trillion in United States Treasury bonds, an investment that helps keep American interest rates low and finances America’s enormous debt.”

It would also be accurate to say that China’s purchase of Treasury bonds “keeps the dollar over-valued and sustains the enormous U.S. trade deficit with China and other countries.”

If China did not purchase these bonds, the dollar would fall against the yuan and other currencies. A lower valued dollar would reduce our imports and increase our exports, moving us closer to balanced trade, increasing U.S. GDP and creating jobs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In an article that discussed the federal government’s policy on offshore oil leases the Washington Post told readers that:

“Democrats and environmentalists say that in a global marketplace, such moves [authorizing offshore drilling] have far less impact on prices than unrest in Libya and other geopolitical factors.”

It is not just Democrats and environmentalists who say this. Anyone who understands markets say this. At most additional offshore drilling can add a few hundred thousand barrels a day to world oil supplies. By contrast, Libya produced about 1.8 million barrels a day before its civil war, Algeria produces 2.1 million barrels and Saudi Arabia produces 9.8 million.

Changes in production by these major producers will have far more impact on the price of gas than our decisions on drilling offshore. People who know economics say this regardless of whether or not they are Democrats or like the environment.

In an article that discussed the federal government’s policy on offshore oil leases the Washington Post told readers that:

“Democrats and environmentalists say that in a global marketplace, such moves [authorizing offshore drilling] have far less impact on prices than unrest in Libya and other geopolitical factors.”

It is not just Democrats and environmentalists who say this. Anyone who understands markets say this. At most additional offshore drilling can add a few hundred thousand barrels a day to world oil supplies. By contrast, Libya produced about 1.8 million barrels a day before its civil war, Algeria produces 2.1 million barrels and Saudi Arabia produces 9.8 million.

Changes in production by these major producers will have far more impact on the price of gas than our decisions on drilling offshore. People who know economics say this regardless of whether or not they are Democrats or like the environment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

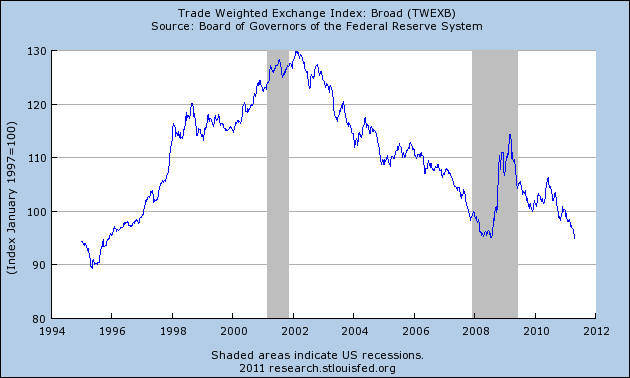

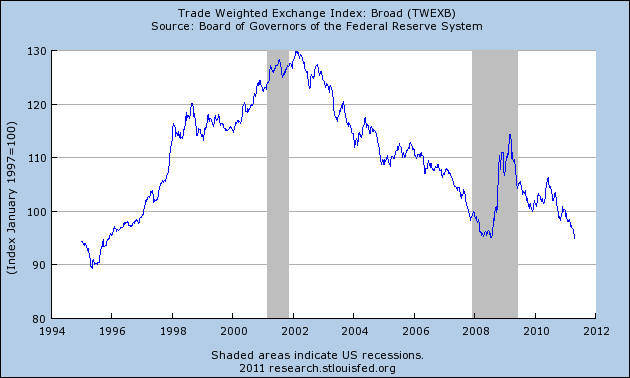

This is what the Post was warning about in its article headlined, “The dollar, at risk: U.S. efforts to speed the economic recovery could transform currency’s slow decline into a precipitous fall,” although it is possible that no one at the paper knows the introductory economics that would allow them to make this connection.

Those who have been through an intro econ class know that the trade surplus is by definition equal to net national savings. This means that countries that have large trade deficits like the United States must by definition have negative net national savings.

The main determinant of the trade surplus (or deficit), given a level of GDP, is the value of the dollar. If the value of the dollar were to fall precipitously, which is presented here as a bad scenario, it would lead to a quick adjustment towards balanced trade through strong growth in net exports. Higher levels of net exports would boost the economy, leading to stronger private savings and a smaller budget deficit. So, the Washington Post headline is actually warning that if we are not careful, we will see stronger economic growth and a smaller budget deficit.

As a practical matter, the precipitous fall in the dollar warned about in the article is almost impossible for exactly this reason. The euro zone countries would not let the dollar fall to 2 dollars to a euro precisely because it would destroy Europe’s export market in the United States and make U.S. goods hyper-competitive in Europe. The same is true of Canada, Japan, China and other U.S. trading partners. If the dollar were for some reason go into a free fall all of these countries would almost certainly actively intervene in currency markets (as China already does) to limit the decline. This should be obvious to anyone who has reflected on the situation for even a minute.

The article gets several other important points wrong. First, the fall in the dollar is only reversing the run-up in the dollar that began with Robert Rubin’s stint as Treasury Secretary. Rubin’s high dollar policy sent the country on the course of bubble driven growth of the late 90s and the 00s that led to record low private savings rate and in last few years, high budget deficits. The recent decline in the dollar is just reversing the Rubin run-up.

The other important fact that the Post got completely wrong was its assertion that:

“History is full of examples of countries where large budget deficits eventually led investors to lose faith, causing the currency to tumble. The Asian financial crisis, which rocked the likes of Thailand, Singapore and South Korea in the late 1990s, is one recent example.”

According to the IMF, in the year prior to the East Asian financial crisis, Thailand had a budget surplus equal to 2.7 percent of GDP. Singapore and South Korea had surpluses equal to 14.4 percent of GDP and 2.6 percent of GDP, respectively. These countries clearly do not support the claim in this article that large budget deficits lead to declining currency values.

This is what the Post was warning about in its article headlined, “The dollar, at risk: U.S. efforts to speed the economic recovery could transform currency’s slow decline into a precipitous fall,” although it is possible that no one at the paper knows the introductory economics that would allow them to make this connection.

Those who have been through an intro econ class know that the trade surplus is by definition equal to net national savings. This means that countries that have large trade deficits like the United States must by definition have negative net national savings.

The main determinant of the trade surplus (or deficit), given a level of GDP, is the value of the dollar. If the value of the dollar were to fall precipitously, which is presented here as a bad scenario, it would lead to a quick adjustment towards balanced trade through strong growth in net exports. Higher levels of net exports would boost the economy, leading to stronger private savings and a smaller budget deficit. So, the Washington Post headline is actually warning that if we are not careful, we will see stronger economic growth and a smaller budget deficit.

As a practical matter, the precipitous fall in the dollar warned about in the article is almost impossible for exactly this reason. The euro zone countries would not let the dollar fall to 2 dollars to a euro precisely because it would destroy Europe’s export market in the United States and make U.S. goods hyper-competitive in Europe. The same is true of Canada, Japan, China and other U.S. trading partners. If the dollar were for some reason go into a free fall all of these countries would almost certainly actively intervene in currency markets (as China already does) to limit the decline. This should be obvious to anyone who has reflected on the situation for even a minute.

The article gets several other important points wrong. First, the fall in the dollar is only reversing the run-up in the dollar that began with Robert Rubin’s stint as Treasury Secretary. Rubin’s high dollar policy sent the country on the course of bubble driven growth of the late 90s and the 00s that led to record low private savings rate and in last few years, high budget deficits. The recent decline in the dollar is just reversing the Rubin run-up.

The other important fact that the Post got completely wrong was its assertion that:

“History is full of examples of countries where large budget deficits eventually led investors to lose faith, causing the currency to tumble. The Asian financial crisis, which rocked the likes of Thailand, Singapore and South Korea in the late 1990s, is one recent example.”

According to the IMF, in the year prior to the East Asian financial crisis, Thailand had a budget surplus equal to 2.7 percent of GDP. Singapore and South Korea had surpluses equal to 14.4 percent of GDP and 2.6 percent of GDP, respectively. These countries clearly do not support the claim in this article that large budget deficits lead to declining currency values.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In the wake of their successful assault on Osama Bin Laden’s hideout, ABC News did a short feature on the Navy Seals. The report tells us that the people who hold this highly demanding and dangerous get paid about $54,000 a yeat. It then adds that:

“The base salary level [of Navy Seals] is comparable to the average annual salary for teachers in the U.S., which was $55,350 for the 2009-2010 school year, according to the Digest of Education Statistics.’

That is one possible comparison. There are other possible reference points. For example, the CEOs of Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan both pocket around $20 million a year. This means that they make almost twice as much in a day as a Navy Seal earns in a year. Not many bank heads have to worry about getting shot in the line of duty.

Of course some Wall Street types do even better. Hedge fund manager John Paulson reportedly pocketed $5 billion last year. If we assume a 3000 hour work year (presumably he had to put in some overtime), Paulson had to work about 2 minutes to earn as much as a Navy Seal does in a year.

In the wake of their successful assault on Osama Bin Laden’s hideout, ABC News did a short feature on the Navy Seals. The report tells us that the people who hold this highly demanding and dangerous get paid about $54,000 a yeat. It then adds that:

“The base salary level [of Navy Seals] is comparable to the average annual salary for teachers in the U.S., which was $55,350 for the 2009-2010 school year, according to the Digest of Education Statistics.’

That is one possible comparison. There are other possible reference points. For example, the CEOs of Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan both pocket around $20 million a year. This means that they make almost twice as much in a day as a Navy Seal earns in a year. Not many bank heads have to worry about getting shot in the line of duty.

Of course some Wall Street types do even better. Hedge fund manager John Paulson reportedly pocketed $5 billion last year. If we assume a 3000 hour work year (presumably he had to put in some overtime), Paulson had to work about 2 minutes to earn as much as a Navy Seal does in a year.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article about a company, Righthaven, that enforces copyrights on the web should have included some comments from economists and conservatives who oppose big government. The specific case highlighted in the article involves a college blogger who posted a picture of an airport security agent doing a pat-down. The Denver Post claims copyright ownership of the picture.

A honest economist would have called attention to the enormous waste in this action. The use of the picture had a value that was almost certainly less than a thousand of a cent, yet this suit could involve thousands of dollars of economic costs in the form of legal fees and court time. It would be difficult to imagine a more wasteful form of government action. (This is a government action, because it is the government that is assigning control over use of this image to the copyright holder.)

Proponents of small government should also be appalled. In this case the government is authorizing private individuals to harass college kids over their efforts to make a point about an issue they care about.

However the NYT did not point out either aspect of this issue. Of course there are far more efficient ways to support creative and artistic work than the copyright, which have their roots in the late Middle Ages. Unfortunately, the NYT and other media outlets almost never mention any alternative mechanism of support.

A NYT article about a company, Righthaven, that enforces copyrights on the web should have included some comments from economists and conservatives who oppose big government. The specific case highlighted in the article involves a college blogger who posted a picture of an airport security agent doing a pat-down. The Denver Post claims copyright ownership of the picture.

A honest economist would have called attention to the enormous waste in this action. The use of the picture had a value that was almost certainly less than a thousand of a cent, yet this suit could involve thousands of dollars of economic costs in the form of legal fees and court time. It would be difficult to imagine a more wasteful form of government action. (This is a government action, because it is the government that is assigning control over use of this image to the copyright holder.)

Proponents of small government should also be appalled. In this case the government is authorizing private individuals to harass college kids over their efforts to make a point about an issue they care about.

However the NYT did not point out either aspect of this issue. Of course there are far more efficient ways to support creative and artistic work than the copyright, which have their roots in the late Middle Ages. Unfortunately, the NYT and other media outlets almost never mention any alternative mechanism of support.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This article discusses the possibility that China may allow the value of its currency to rise relative to the dollar. At one point it notes that China has an enormous trade surplus with the current valuation (according to economic theory, a fast growing developing country should have an enormous trade deficit). It then points out that the dollars obtained with this surplus are used to buy Treasury bonds, that “some Chinese argue [are] risky.”

It is worth noting that this is little real risk to China in holding these bonds, they are virtually guaranteed to lose money. There is no way that they can hope to ever sell off their huge holdings without seeing a large reduction in the value of the dollar (and therefore the value of their holdings). The Chinese government is presumably willing to see this loss in order to maintain its export markets in the United States and elsewhere.

This article discusses the possibility that China may allow the value of its currency to rise relative to the dollar. At one point it notes that China has an enormous trade surplus with the current valuation (according to economic theory, a fast growing developing country should have an enormous trade deficit). It then points out that the dollars obtained with this surplus are used to buy Treasury bonds, that “some Chinese argue [are] risky.”

It is worth noting that this is little real risk to China in holding these bonds, they are virtually guaranteed to lose money. There is no way that they can hope to ever sell off their huge holdings without seeing a large reduction in the value of the dollar (and therefore the value of their holdings). The Chinese government is presumably willing to see this loss in order to maintain its export markets in the United States and elsewhere.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

According to the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) analysis, Representative Paul Ryan’s plan for privatizing Medicare would raise the cost to the country (the combined cost to the government and beneficiaries) of providing Medicare equivalent policies by $34 trillion over the program’s 75-year planning horizon. This is a number that is so huge that it difficult for many people to understand it.

This number comes to roughly $110,000 for every man, woman, and child in the country. It is almost 7 times as large as the projected shortfall in Social Security that has so many people in Washington terrified.

It turns out that even health care reporters have a difficult time understanding how much the Ryan plan is projected to raise costs. The Kaiser Health News Service told readers that CBO’s projections show that the Ryan plan would raise the portion of the health care premium paid by beneficiaries in 2030 from 25 percent to 68 percent.

Actually, those looking at the CBO projections (Figure 1) will see that under the Ryan plan beneficiaries do pay 68 percent of the cost of a Medicare equivalent policy in 2030. They will also see that the baseline projection shows them paying just 25 percent of the cost. Except the figure also shows that the baseline Medicare policy only costs 60 percent as much as the Medicare equivalent policy under the Ryan plan.

This means that to make an apples to apples comparison, we would have to multiply the beneficiary’s 25 percent contribution by 60 percent, to get that they would pay 15 percent of the cost of a Medicare equivalent policy under the Ryan plan. While the increase in the beneficiary’s contribution reported by Kaiser might have sounded like a huge burden, it actually understates the change. If we use the cost of a Medicare equivalent policy under the Ryan plan as the denominator, the beneficiary’s contribution goes from 15 percent under the existing system to 68 percent under the Ryan plan.

Addendum:

Actually, looking at this with better eyes, Kaiser did report the CBO numbers correctly. They expressed the beneficiary’s contribution under the existing Medicare program as a percent of the cost under a Medicare equivalent policy under the Ryan plan. There was a slight misstatement, since the payment would be 41.7 percent of the cost of the policy to Medicare, but for purposes of the analysis it is appropriate to show the payment as a share of the cost under the Ryan plan so that readers can make an apples to apples to comparison.

The chart accompanying this piece does get the issue confused. According to the CBO analysis, beneficiaries currently pay 39.3 percent of the total cost of a Medicare policy provided through the traditional Medicare system. This would be equal to 35 percent of the cost of a Medicare equivalent plan provided through a privatized system. This shares rises to 68 percent of the cost of a Medicare equivalent plan by 2030.

According to the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) analysis, Representative Paul Ryan’s plan for privatizing Medicare would raise the cost to the country (the combined cost to the government and beneficiaries) of providing Medicare equivalent policies by $34 trillion over the program’s 75-year planning horizon. This is a number that is so huge that it difficult for many people to understand it.

This number comes to roughly $110,000 for every man, woman, and child in the country. It is almost 7 times as large as the projected shortfall in Social Security that has so many people in Washington terrified.

It turns out that even health care reporters have a difficult time understanding how much the Ryan plan is projected to raise costs. The Kaiser Health News Service told readers that CBO’s projections show that the Ryan plan would raise the portion of the health care premium paid by beneficiaries in 2030 from 25 percent to 68 percent.

Actually, those looking at the CBO projections (Figure 1) will see that under the Ryan plan beneficiaries do pay 68 percent of the cost of a Medicare equivalent policy in 2030. They will also see that the baseline projection shows them paying just 25 percent of the cost. Except the figure also shows that the baseline Medicare policy only costs 60 percent as much as the Medicare equivalent policy under the Ryan plan.

This means that to make an apples to apples comparison, we would have to multiply the beneficiary’s 25 percent contribution by 60 percent, to get that they would pay 15 percent of the cost of a Medicare equivalent policy under the Ryan plan. While the increase in the beneficiary’s contribution reported by Kaiser might have sounded like a huge burden, it actually understates the change. If we use the cost of a Medicare equivalent policy under the Ryan plan as the denominator, the beneficiary’s contribution goes from 15 percent under the existing system to 68 percent under the Ryan plan.

Addendum:

Actually, looking at this with better eyes, Kaiser did report the CBO numbers correctly. They expressed the beneficiary’s contribution under the existing Medicare program as a percent of the cost under a Medicare equivalent policy under the Ryan plan. There was a slight misstatement, since the payment would be 41.7 percent of the cost of the policy to Medicare, but for purposes of the analysis it is appropriate to show the payment as a share of the cost under the Ryan plan so that readers can make an apples to apples to comparison.

The chart accompanying this piece does get the issue confused. According to the CBO analysis, beneficiaries currently pay 39.3 percent of the total cost of a Medicare policy provided through the traditional Medicare system. This would be equal to 35 percent of the cost of a Medicare equivalent plan provided through a privatized system. This shares rises to 68 percent of the cost of a Medicare equivalent plan by 2030.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson is concerned that Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke is insufficiently concerned about inflation. This might seem a strange concern to those of us in the real world. After all, core prices have risen by 1.2 percent over the last year. That’s nearly a full percentage point below the Fed’s target rate.

Low inflation creates serious problems for the economy. It prevents the real interest from being as low as would be desired given the weakness of the economy. (The real interest rate is the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate. Since the nominal interest rate cannot fall below zero, the inflation rate sets the extent to which the real interest rate can turn negative.) Low inflation also leaves a large debt burden on households who have large debts due to the collapse of the housing bubble. These are the reasons that most economists would like to see a somewhat higher rate of inflation.

However Samuelson argues the opposite, he is concerned that inflation is already too high. He notes the run-up in oil and food prices. Of course these prices are determined in a world market, it is difficult to see how anything Bernanke could do, short of crashing the U.S. economy, could have more than a marginal impact on them.

Samuelson then turns to other prices. He notes rapidly rising airline prices. Samuelson apparently didn’t know that airlines use jet fuel, which is made with oil.

His other example is car prices. He tells readers that:

“Car ‘incentives’ (a.k.a. price discounts) are shrinking — which means prices are rising.”

Yes, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us that car prices have risen 1.6 percent over the last year. Yep, that’s Zimbabwe-style hyperinflation. They don’t call it “Fox on 15th Street” for nothing.

Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson is concerned that Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke is insufficiently concerned about inflation. This might seem a strange concern to those of us in the real world. After all, core prices have risen by 1.2 percent over the last year. That’s nearly a full percentage point below the Fed’s target rate.

Low inflation creates serious problems for the economy. It prevents the real interest from being as low as would be desired given the weakness of the economy. (The real interest rate is the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate. Since the nominal interest rate cannot fall below zero, the inflation rate sets the extent to which the real interest rate can turn negative.) Low inflation also leaves a large debt burden on households who have large debts due to the collapse of the housing bubble. These are the reasons that most economists would like to see a somewhat higher rate of inflation.

However Samuelson argues the opposite, he is concerned that inflation is already too high. He notes the run-up in oil and food prices. Of course these prices are determined in a world market, it is difficult to see how anything Bernanke could do, short of crashing the U.S. economy, could have more than a marginal impact on them.

Samuelson then turns to other prices. He notes rapidly rising airline prices. Samuelson apparently didn’t know that airlines use jet fuel, which is made with oil.

His other example is car prices. He tells readers that:

“Car ‘incentives’ (a.k.a. price discounts) are shrinking — which means prices are rising.”

Yes, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us that car prices have risen 1.6 percent over the last year. Yep, that’s Zimbabwe-style hyperinflation. They don’t call it “Fox on 15th Street” for nothing.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

What is wrong with news outlets who can’t report on the deficit/debt without giving us silly morality tales? The NYT tells us this morning that:

“Republicans see the vote over raising the debt limit as leverage for immediate and concrete progress in their efforts to cut spending and reduce the size and reach of the government.”

Really? How does the NYT know how the Republicans “see” the vote over raising the debt limit. It would be equally valid to say that:

“Republicans see the vote over raising the debt limit as leverage for cutting spending on broad-based social programs like Social Security and provide more tax cuts to the wealthy as part of their efforts to redistribute income upward.”

Is there any evidence that upward redistribution on income is the Republicans’ goal? That certainly is the impact of their policies (actually of many of the Democrats’ policies also) so a newspaper could with considerable validity make this assertion.

Serious newspapers don’t pretend to know what politicians’ motives are. They just tell their audience what they do and say.

What is wrong with news outlets who can’t report on the deficit/debt without giving us silly morality tales? The NYT tells us this morning that:

“Republicans see the vote over raising the debt limit as leverage for immediate and concrete progress in their efforts to cut spending and reduce the size and reach of the government.”

Really? How does the NYT know how the Republicans “see” the vote over raising the debt limit. It would be equally valid to say that:

“Republicans see the vote over raising the debt limit as leverage for cutting spending on broad-based social programs like Social Security and provide more tax cuts to the wealthy as part of their efforts to redistribute income upward.”

Is there any evidence that upward redistribution on income is the Republicans’ goal? That certainly is the impact of their policies (actually of many of the Democrats’ policies also) so a newspaper could with considerable validity make this assertion.

Serious newspapers don’t pretend to know what politicians’ motives are. They just tell their audience what they do and say.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión