In years past news reports regularly repeated auto company assertions that their UAW workers earned in excess of $70 an hour. Thankfully this inaccurate claim seems to have been largely missing from news reports in recent months.

But, now it is back in the NYT. Our old friend arithmetic can show the problem. We know that the average UAW worker gets roughly $28 an hour in pay. (This is on the old pay scale, many new workers get as little as $14 an hour.) This leaves us with at least $42 an hour going to health insurance, pensions, and other benefits. With a 2000 hour work year this would imply $84,000 a year going to these benefits.

UAW workers do get good health care benefits, but does the average benefit exceed $20,000 a year? That seems pretty unlikely. The pensions are also comparatively generous, but it is a safe bet that GM is not contributing more than $25,000 a year to their workers’ pensions on average.

The way that the industry got their $70 plus an hour figure was by including the cost of payments for retirees (e.g. health care benefits for already retired workers) and averaging them over their current workforce. This may be useful for the companies accounting, but it has nothing to do with what current workers actually receive in wages and benefits.

In years past news reports regularly repeated auto company assertions that their UAW workers earned in excess of $70 an hour. Thankfully this inaccurate claim seems to have been largely missing from news reports in recent months.

But, now it is back in the NYT. Our old friend arithmetic can show the problem. We know that the average UAW worker gets roughly $28 an hour in pay. (This is on the old pay scale, many new workers get as little as $14 an hour.) This leaves us with at least $42 an hour going to health insurance, pensions, and other benefits. With a 2000 hour work year this would imply $84,000 a year going to these benefits.

UAW workers do get good health care benefits, but does the average benefit exceed $20,000 a year? That seems pretty unlikely. The pensions are also comparatively generous, but it is a safe bet that GM is not contributing more than $25,000 a year to their workers’ pensions on average.

The way that the industry got their $70 plus an hour figure was by including the cost of payments for retirees (e.g. health care benefits for already retired workers) and averaging them over their current workforce. This may be useful for the companies accounting, but it has nothing to do with what current workers actually receive in wages and benefits.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Standard & Poor’s, which is probably best known for giving investment grade rating to mortgage backed securities backed by junk mortgages at the peak of the bubble, warned that demographic changes would pose severe budget burdens and urged the United States to begin to begin cutting back programs for the elderly now. In an article presenting Standard & Poor’s view on this issue, it would have been worth reminding readers of the company’s track record. It probably would also have been appropriate to remind readers that it was paid large amounts of money for the investment grade ratings it gave to these mortgage backed securities.

This background would allow readers to better assess the nature of Standard and Poor’s advice to the American people. Economists who are not paid by Wall Street banks have used the exact same data to point out that the projected budget problems are due to the incredible inefficiency of the U.S. health care system. If the United States paid the same per person costs as any other wealthy country the long-term projections would show huge budget surpluses, not deficits.

Standard & Poor’s, which is probably best known for giving investment grade rating to mortgage backed securities backed by junk mortgages at the peak of the bubble, warned that demographic changes would pose severe budget burdens and urged the United States to begin to begin cutting back programs for the elderly now. In an article presenting Standard & Poor’s view on this issue, it would have been worth reminding readers of the company’s track record. It probably would also have been appropriate to remind readers that it was paid large amounts of money for the investment grade ratings it gave to these mortgage backed securities.

This background would allow readers to better assess the nature of Standard and Poor’s advice to the American people. Economists who are not paid by Wall Street banks have used the exact same data to point out that the projected budget problems are due to the incredible inefficiency of the U.S. health care system. If the United States paid the same per person costs as any other wealthy country the long-term projections would show huge budget surpluses, not deficits.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what AP told readers today. Tomorrow we will no doubt find that many scientists believe that the earth is round and that humans evolved from more primitive primates. Stay tuned.

That’s what AP told readers today. Tomorrow we will no doubt find that many scientists believe that the earth is round and that humans evolved from more primitive primates. Stay tuned.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Thomas Friedman devoted his column this morning to criticize an effort by the oil firms to roll back environmental regulation in California. The effort takes the form of a referendum that would delay rules requiring greater energy efficiency until the unemployment rate is below 5.5 percent.

While this sequence appears to be motivated by a concern for California’s economy, the logic goes in the opposite direction. In periods of high unemployment investments in more efficient technology have very little cost to California since they are likely to employ workers who would otherwise be idle. In fact, by requiring California firms to invest in clean technology the regulations could well be net job creators.

By contrast, in standard economic theory environmental regulations will pull workers away from other sectors in periods of full employment. This would raise costs and therefore reduce total output and employment. From an economic standpoint it would make more sense to only require firms to take steps to reduce emissions when the unemployment rate is above 5.5 percent rather than below.

Thomas Friedman devoted his column this morning to criticize an effort by the oil firms to roll back environmental regulation in California. The effort takes the form of a referendum that would delay rules requiring greater energy efficiency until the unemployment rate is below 5.5 percent.

While this sequence appears to be motivated by a concern for California’s economy, the logic goes in the opposite direction. In periods of high unemployment investments in more efficient technology have very little cost to California since they are likely to employ workers who would otherwise be idle. In fact, by requiring California firms to invest in clean technology the regulations could well be net job creators.

By contrast, in standard economic theory environmental regulations will pull workers away from other sectors in periods of full employment. This would raise costs and therefore reduce total output and employment. From an economic standpoint it would make more sense to only require firms to take steps to reduce emissions when the unemployment rate is above 5.5 percent rather than below.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post had a front page piece that highlighted efforts to cut pensions for state and local workers. The piece told readers that there is declining support for public sector workers because many people resent the fact that they have been forced to take pay cuts while public sector workers often have had their pay and benefits protected.

It is worth noting that major media outlets, like the Washington Post, routinely highlight and often exaggerate the pay and benefits received by public sector workers. In contrast, they deliberately mislead their audience about the extent of public support for major Wall Street banks.

For example, media outlets have repeatedly highlighted the fact that most of the TARP loans to the banks have been repaid without pointing out that these banks benefited enormously from having access to trillions of dollars in loans and loan guarantees at below market interest rates. Without these guarantees Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America and many other large banks would have gone bankrupt. Their shareholders would have lost hundreds of billions of dollars, freeing up wealth for non-Wall Street America. And their top executives would not be drawing pay in the tens of millions of dollars (@100 public sector worker pensions).

Major media outlets have acted almost as though they were conducting a political campaign. They have flooded the public with reports minimizing the cost to the public of the Wall Street bailouts while putting out endless stories (many largely false) about overpaid public sector workers.

The Post had a front page piece that highlighted efforts to cut pensions for state and local workers. The piece told readers that there is declining support for public sector workers because many people resent the fact that they have been forced to take pay cuts while public sector workers often have had their pay and benefits protected.

It is worth noting that major media outlets, like the Washington Post, routinely highlight and often exaggerate the pay and benefits received by public sector workers. In contrast, they deliberately mislead their audience about the extent of public support for major Wall Street banks.

For example, media outlets have repeatedly highlighted the fact that most of the TARP loans to the banks have been repaid without pointing out that these banks benefited enormously from having access to trillions of dollars in loans and loan guarantees at below market interest rates. Without these guarantees Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America and many other large banks would have gone bankrupt. Their shareholders would have lost hundreds of billions of dollars, freeing up wealth for non-Wall Street America. And their top executives would not be drawing pay in the tens of millions of dollars (@100 public sector worker pensions).

Major media outlets have acted almost as though they were conducting a political campaign. They have flooded the public with reports minimizing the cost to the public of the Wall Street bailouts while putting out endless stories (many largely false) about overpaid public sector workers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

According to the New York Times, Scott Walker, the Republican candidate for governor is worried that they can’t. Of course, the NYT did not make the issue quite this clear to readers.

It told readers that Mr. Walker is worried that subsidies to high speed rail could cost Wisconsin $7-$10 million a year. It would be necessary to divide by Wisconsin’s population of 5.6 million to realize that an expenditure of 2.8-4.0 cents a week is a high item on the Republican gubernatorial candidate’s list of concerns.

(Thanks C. Mike for catching my initial error.)

According to the New York Times, Scott Walker, the Republican candidate for governor is worried that they can’t. Of course, the NYT did not make the issue quite this clear to readers.

It told readers that Mr. Walker is worried that subsidies to high speed rail could cost Wisconsin $7-$10 million a year. It would be necessary to divide by Wisconsin’s population of 5.6 million to realize that an expenditure of 2.8-4.0 cents a week is a high item on the Republican gubernatorial candidate’s list of concerns.

(Thanks C. Mike for catching my initial error.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what readers of Andrew Ross Sorkin’s column on AIG are all asking, but arithmetic and Mr. Sorkin are rarely found in the same room. Of course the real story of AIG and the other bailouts is that the government used its credit to keep the company, and more importantly its creditors and top executives in business.

Sorkin apparently assumes his readers do not understand that below market loans and guarantees have enormous value. Of course if the government had made the same commitments to the owner of a corner hot-dog stand as it did to AIG, this person would be as rich as Bill Gates right now. Mr. Sorkin could then write a column about how the loans and guarantees didn’t cost the government anything (since the hot-dog stand owner had repaid them), but NYT readers know better.

That’s what readers of Andrew Ross Sorkin’s column on AIG are all asking, but arithmetic and Mr. Sorkin are rarely found in the same room. Of course the real story of AIG and the other bailouts is that the government used its credit to keep the company, and more importantly its creditors and top executives in business.

Sorkin apparently assumes his readers do not understand that below market loans and guarantees have enormous value. Of course if the government had made the same commitments to the owner of a corner hot-dog stand as it did to AIG, this person would be as rich as Bill Gates right now. Mr. Sorkin could then write a column about how the loans and guarantees didn’t cost the government anything (since the hot-dog stand owner had repaid them), but NYT readers know better.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That would be Ben Bernanke, who by his own claim brought us to the edge of a second Great Depression. The Post told readers that Bernanke:

“has aimed to use the weight of his words to try to give more momentum to efforts to reduce the budget deficit in the medium to long term.”

It would have been reasonable to note the irony that a person who failed so miserably at his job — causing tens of millions to be unemployed or underemployed, and also causing deficits to soar — would lecture Congress and the public about deficits.

That would be Ben Bernanke, who by his own claim brought us to the edge of a second Great Depression. The Post told readers that Bernanke:

“has aimed to use the weight of his words to try to give more momentum to efforts to reduce the budget deficit in the medium to long term.”

It would have been reasonable to note the irony that a person who failed so miserably at his job — causing tens of millions to be unemployed or underemployed, and also causing deficits to soar — would lecture Congress and the public about deficits.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

What do conservatives have against reality? That is undoubtedly the question that readers of David Leonhardt’s Economix blogpost on the revaluation of China’s currency will be asking. Leonhardt turned the post over to Derek Scissors of the Heritage Foundation.

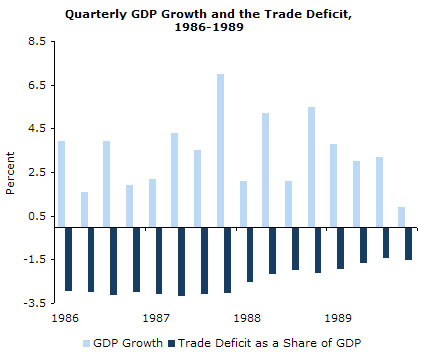

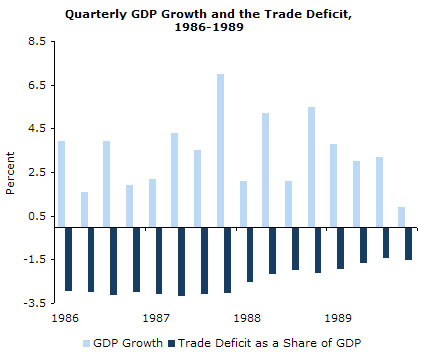

Mr. Scissors argues that the rise in the value of the Japanese yen in the 80s had little to do with the decline in the U.S. trade deficit with Japan. Scissors argued that the trade deficit just shifted to China. He claims that the main reason that the deficit fell in the 80s was the slowdown in growth and the onset of the recession.

There is a small problem with that argument. The trade deficit dropped while the economy was still growing rapidly. It fell from a peak of 3.1 percent of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 1987 to less than 2.0 percent of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 1988, as shown in the graph below. This quarter was sandwiched between two quarters of growth above 5.0 percent. The deficit declined further to less than 1.4 percent of GDP by the 3rd quarter of 1989, when the economy grew 3.2 percent.

In short, the recession cannot explain the decline in the size of the trade deficit because the deficit declined while the economy was still growing rapidly. The more obvious explanation is the decline in the value of the dollar that was negotiated at the Plaza Accords in 1986. This is yet another example of the facts being biased against conservatives.

What do conservatives have against reality? That is undoubtedly the question that readers of David Leonhardt’s Economix blogpost on the revaluation of China’s currency will be asking. Leonhardt turned the post over to Derek Scissors of the Heritage Foundation.

Mr. Scissors argues that the rise in the value of the Japanese yen in the 80s had little to do with the decline in the U.S. trade deficit with Japan. Scissors argued that the trade deficit just shifted to China. He claims that the main reason that the deficit fell in the 80s was the slowdown in growth and the onset of the recession.

There is a small problem with that argument. The trade deficit dropped while the economy was still growing rapidly. It fell from a peak of 3.1 percent of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 1987 to less than 2.0 percent of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 1988, as shown in the graph below. This quarter was sandwiched between two quarters of growth above 5.0 percent. The deficit declined further to less than 1.4 percent of GDP by the 3rd quarter of 1989, when the economy grew 3.2 percent.

In short, the recession cannot explain the decline in the size of the trade deficit because the deficit declined while the economy was still growing rapidly. The more obvious explanation is the decline in the value of the dollar that was negotiated at the Plaza Accords in 1986. This is yet another example of the facts being biased against conservatives.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT discussed the issues involved in currency pricing and trade protection with reference to China and other countries. The article raised concerns that growing protectionism could hurt economic growth, but it never noted that most highly educated professionals already benefit from extensive protectionism. The inequality resulting from their protection is one of the key factors motivating protectionist sentiments in the United States.

It also raises the prospect that a higher valued yuan would seriously damage China’s economy. It would have been helpful to note the importance of China’s exports to the U.S. to its economy. China’s good exports to the U.S. are approximately equal to 6 percent of its GDP. Even a sharp rise in the yuan is unlikely to reduce its exports by more than one-third (2 percent of GDP) over a 2-year period. This is currently equal to less than 3 months of growth in China.

It is also worth noting that China’s exports to the United States fell by 17.4 percent from the third quarter of 2008 to the third quarter of 2009. China was able to offset the loss of export demand from the United States and elsewhere with a massive stimulus package. As a result, its economy grew by more than 9.0 percent in 2009.

The NYT discussed the issues involved in currency pricing and trade protection with reference to China and other countries. The article raised concerns that growing protectionism could hurt economic growth, but it never noted that most highly educated professionals already benefit from extensive protectionism. The inequality resulting from their protection is one of the key factors motivating protectionist sentiments in the United States.

It also raises the prospect that a higher valued yuan would seriously damage China’s economy. It would have been helpful to note the importance of China’s exports to the U.S. to its economy. China’s good exports to the U.S. are approximately equal to 6 percent of its GDP. Even a sharp rise in the yuan is unlikely to reduce its exports by more than one-third (2 percent of GDP) over a 2-year period. This is currently equal to less than 3 months of growth in China.

It is also worth noting that China’s exports to the United States fell by 17.4 percent from the third quarter of 2008 to the third quarter of 2009. China was able to offset the loss of export demand from the United States and elsewhere with a massive stimulus package. As a result, its economy grew by more than 9.0 percent in 2009.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión