President Biden’s budget calls for quadrupling the tax on share buybacks to 4.0 percent. This is a great way to raise revenue, since it is probably the most efficient tax ever devised.

The neat thing about taxing share buybacks is that they are publicly announced. Companies have to tell shareholders that they are buying back shares.

If management lies, they don’t just have to worry about the government, they have to worry about their own shareholders. Management would then both face serious civil and criminal penalties. They might be willing to rip off shareholders to fatten their own paychecks, but few CEOs will risk their own wealth, as well as jail time, to save their company a few dollars on taxes.

The Biden administration projected that increasing this tax would raise $160 billion over the next decade. This is not huge in terms of the federal budget (it’s a bit more than 0.2 percent of projected spending), but on an annual basis, the $16 billion it would raise is roughly one-fourth of the amount at stake in Biden’s aid request for Ukraine.

While some have demonized share buybacks, it is hard to see why they are any worse than paying out money to shareholders as dividends. Insofar as this tax changes corporate behavior it will most likely be to get them to pay more money in dividends and use less for share buybacks. That’s fine, but no one should expect an investment boom from taxing share buybacks.

The big benefit from the buyback tax is that it can be a step towards shifting the basis of the corporate income tax from profits to returns to shareholders (dividends plus capital gains). The reason why this is such a big deal is that this shift would effectively put the tax gaming industry out of business.

The I.R.S. can’t see corporate profits directly, they have to rely on corporate accountants to tell them what their companies’ profits are. These accountants have an enormous incentive to find ways to game the tax code to make their taxable profits look less than their actual profits.

The accountants and their lawyer accomplices have developed hundreds of elaborate schemes to hide profits with various tricks and maximize the value of every loophole. Tens of billions of dollars is wasted every year running these schemes with much investment shifted for no reason other than to reduce tax liabilities.

If instead the basis for the corporate income tax was stock returns, we don’t have to care what the accountants say or do. This information is publicly available on dozens of financial websites. The I.R.S. could in a matter of minutes calculate the tax liability of every publicly traded corporation in the country on a single spreadsheet.

The only way to get out of paying the tax a company owes would be for the management to cheat their shareholders. Again, that is not likely to be a very promising path, since they could end up paying large fines and going to jail. Rich shareholders don’t like to be cheated.

There are some issues, but they are trivial compared to the current system. We would probably want to allow some sort of averaging so that a company whose stock suddenly surged would not face a huge tax liability in that year. On the other hand, if the surge proved enduring, they would have a high tax bill, which is appropriate. (If they don’t have a lot of cash on hand to pay their taxes, they could always sell shares.)

There is also an issue of allocating the returns across countries. This is the same problem we have now with the profits-based tax. The obvious solution is to divide the tax among countries in accordance with their share of revenue from each one. That may not be perfect, but there will never be a perfect tax system.

Note that this switch says nothing about tax rates, we can make the tax rate 5.0 percent or 35.0 percent, the point is that whatever rate we set, we can know that we will collect it. And we know that companies will not waste huge amounts of resources trying to avoid or evade the tax because they won’t be able to do it.

This switch would be a huge victory for those who want to see a fair and efficient tax system. The tax on buybacks is a big step down this path, with a bit of luck we will be able to go the rest of the way.

President Biden’s budget calls for quadrupling the tax on share buybacks to 4.0 percent. This is a great way to raise revenue, since it is probably the most efficient tax ever devised.

The neat thing about taxing share buybacks is that they are publicly announced. Companies have to tell shareholders that they are buying back shares.

If management lies, they don’t just have to worry about the government, they have to worry about their own shareholders. Management would then both face serious civil and criminal penalties. They might be willing to rip off shareholders to fatten their own paychecks, but few CEOs will risk their own wealth, as well as jail time, to save their company a few dollars on taxes.

The Biden administration projected that increasing this tax would raise $160 billion over the next decade. This is not huge in terms of the federal budget (it’s a bit more than 0.2 percent of projected spending), but on an annual basis, the $16 billion it would raise is roughly one-fourth of the amount at stake in Biden’s aid request for Ukraine.

While some have demonized share buybacks, it is hard to see why they are any worse than paying out money to shareholders as dividends. Insofar as this tax changes corporate behavior it will most likely be to get them to pay more money in dividends and use less for share buybacks. That’s fine, but no one should expect an investment boom from taxing share buybacks.

The big benefit from the buyback tax is that it can be a step towards shifting the basis of the corporate income tax from profits to returns to shareholders (dividends plus capital gains). The reason why this is such a big deal is that this shift would effectively put the tax gaming industry out of business.

The I.R.S. can’t see corporate profits directly, they have to rely on corporate accountants to tell them what their companies’ profits are. These accountants have an enormous incentive to find ways to game the tax code to make their taxable profits look less than their actual profits.

The accountants and their lawyer accomplices have developed hundreds of elaborate schemes to hide profits with various tricks and maximize the value of every loophole. Tens of billions of dollars is wasted every year running these schemes with much investment shifted for no reason other than to reduce tax liabilities.

If instead the basis for the corporate income tax was stock returns, we don’t have to care what the accountants say or do. This information is publicly available on dozens of financial websites. The I.R.S. could in a matter of minutes calculate the tax liability of every publicly traded corporation in the country on a single spreadsheet.

The only way to get out of paying the tax a company owes would be for the management to cheat their shareholders. Again, that is not likely to be a very promising path, since they could end up paying large fines and going to jail. Rich shareholders don’t like to be cheated.

There are some issues, but they are trivial compared to the current system. We would probably want to allow some sort of averaging so that a company whose stock suddenly surged would not face a huge tax liability in that year. On the other hand, if the surge proved enduring, they would have a high tax bill, which is appropriate. (If they don’t have a lot of cash on hand to pay their taxes, they could always sell shares.)

There is also an issue of allocating the returns across countries. This is the same problem we have now with the profits-based tax. The obvious solution is to divide the tax among countries in accordance with their share of revenue from each one. That may not be perfect, but there will never be a perfect tax system.

Note that this switch says nothing about tax rates, we can make the tax rate 5.0 percent or 35.0 percent, the point is that whatever rate we set, we can know that we will collect it. And we know that companies will not waste huge amounts of resources trying to avoid or evade the tax because they won’t be able to do it.

This switch would be a huge victory for those who want to see a fair and efficient tax system. The tax on buybacks is a big step down this path, with a bit of luck we will be able to go the rest of the way.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

When we hear about inflation most of us probably think of items like food, gas, and rent, but when it comes to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the most frequently cited measure of inflation, auto insurance has played a very large role in recent years. The index for motor vehicle insurance rose 0.9 percent in July and was responsible for 0.024 percentage points of the 0.4 percent inflation reported for February.

Over the last year the insurance index has risen 20.6 percent and is responsible for just over 0.5 percentage points of the 3.2 percent inflation rate in the overall CPI. It accounts for more than 0.6 percentage points of the 3.8 percent inflation shown in the core index over the last year. We would likely be thinking about inflation very differently if the auto insurance index showed a more moderate rate of inflation.

Part of the story with rising auto insurance prices reflects inflation in the relevant sectors of the economy. New and used car prices rose rapidly in the pandemic due to supply chain problems. We also saw a big increase in the price of car parts for the same reason. And, auto repair prices also rose rapidly, partly due to higher prices for parts, but also due to labor shortages pushing up pay in the industry.

This part of the insurance inflation story is diminishing as inflation in these components comes under control. New vehicle prices have risen just 0.4 percent over the last year and used vehicle prices are down 1.6 percent.

The index for parts and equipment fell 0.5 percent over the last year, after peaking with a year over year increase of more than 15 percent in 2022. The index for maintenance and repairs rose 6.7 percent over the last year, but that is down from a peak of 14.2 percent at the start of last year.

These inflation-driven aspects of auto insurance prices are coming under control, but that is only part of the story of the rise in the insurance index. The other part is simply that there is more damage to cars and passengers.

There are many factors here. We have seen a rise in accident rates since the pandemic. There also is more damage due to climate-related events like hurricanes and flooding. Insofar as these factors lead to higher insurance premiums, this will be picked up in the CPI insurance index, since it simply measures the premiums that drivers pay.

This is in contrast to the auto insurance component of the Personal Consumption Expenditure Deflator (PCE). That component uses a net measure of the cost of auto insurance, which subtracts out the amount paid to customers in claims.

The insurance component in the PCE has a much lower weight in the index, just 0.57 percent, compared to 2.83 percent in the CPI. It also shows a considerably lower rate of inflation, rising just 6.6 percent over the last year.

What Should Count as Inflation?

This differing treatment raises an interesting conceptual issue about how we think about the CPI, inflation, and the cost of living. The CPI measures the change in the price of a fixed basket of goods and services. The basket changes every year, but it doesn’t pick up the effect of people switching, say from beef to chicken, in response to a change in relative prices, if beef prices rise more than chicken prices.

This issue has often been raised as a reason the CPI is inadequate as a measure of the cost of living, meaning that it overstates the true increase in the cost of living. In reality, this sort of “substitution” actually doesn’t matter much. An index that allows for the effect of substitution, like the PCE, shows a 0.2-0.3 pp lower rate of inflation. That can add up over time, but it doesn’t really qualitatively change our view of inflation.

The more important issue is how we deal with societal changes, as is happening with auto insurance. Suppose auto insurance costs more because more bad things are happening, like accidents or floods destroying cars. The PCE measure of insurance would not show this as an increase in the cost of living. The logic is that we are not actually paying a higher price for the same insurance, we are paying more because we are effectively getting more insurance.

This is in some sense true, but the only reason we need to buy more insurance is because drivers have become more reckless, or climate change is causing more damage. These changes have increased our cost of living, but in ways that may not be picked up in measured inflation.

To take a similar story, suppose crime in a neighborhood has exploded. Now people routinely get burglar alarms, put in extra locks and bars on windows, and get vicious dogs to discourage intruders. These are all higher costs that these people will incur, but none of them are included in the CPI or any other inflation measure.

Healthcare presents similar problems. Our inflation indexes measure the cost of specific treatments. But we don’t actually value the treatments — most of us would probably be happy never having to see the doctor – we value our health.

When a new disease appears, like Covid in 2020 or AIDS in the 1980s, the cost of treatment for the new disease is not factored into the inflation indexes. In fact, when the cost of a treatment declines, as when a drug goes off patent and the availability of generics drive down the price, the new disease has the effect of lowering the measured rate of inflation.

To my view, the best way to measure the cost of healthcare in an inflation index is to measure what we pay and simply deduct it from our disposable income. We have separate measures to evaluate health. People’s health may improve because they eat better, exercise more, or have a healthier environment. These outcomes imply an improvement in living standards in most people’s book even if we are not getting more drugs, tests, or medical procedures.

We also have problems that items become necessities, but the associated spending is not picked up in the CPI or other inflation measures. The Internet is great but try getting by without it. It really is necessary now to be on-line to be able to get access to a wide swath of information, much of which used to be available through other channels. (Have you seen a phone book lately?).

However, the cost of monthly Internet access, or the device needed to get on the Internet (phone or computer), does not appear as increase in the cost of living in our inflation indexes. There are many other items that fall into the same category. A car could be considered a luxury for most people 70 years ago. Now that many cities are pretty much designed around cars, it would be very difficult to get around without one.

Anyhow, this is a long way of saying that the cost of living can be a difficult concept. The CPI’s treatment of car insurance provides an interesting window on the issue. This measure is one way in which the effects of global warming will show up in the measured rate of inflation. Unfortunately, it is not the only way in which it will affect the cost-of-living.

When we hear about inflation most of us probably think of items like food, gas, and rent, but when it comes to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the most frequently cited measure of inflation, auto insurance has played a very large role in recent years. The index for motor vehicle insurance rose 0.9 percent in July and was responsible for 0.024 percentage points of the 0.4 percent inflation reported for February.

Over the last year the insurance index has risen 20.6 percent and is responsible for just over 0.5 percentage points of the 3.2 percent inflation rate in the overall CPI. It accounts for more than 0.6 percentage points of the 3.8 percent inflation shown in the core index over the last year. We would likely be thinking about inflation very differently if the auto insurance index showed a more moderate rate of inflation.

Part of the story with rising auto insurance prices reflects inflation in the relevant sectors of the economy. New and used car prices rose rapidly in the pandemic due to supply chain problems. We also saw a big increase in the price of car parts for the same reason. And, auto repair prices also rose rapidly, partly due to higher prices for parts, but also due to labor shortages pushing up pay in the industry.

This part of the insurance inflation story is diminishing as inflation in these components comes under control. New vehicle prices have risen just 0.4 percent over the last year and used vehicle prices are down 1.6 percent.

The index for parts and equipment fell 0.5 percent over the last year, after peaking with a year over year increase of more than 15 percent in 2022. The index for maintenance and repairs rose 6.7 percent over the last year, but that is down from a peak of 14.2 percent at the start of last year.

These inflation-driven aspects of auto insurance prices are coming under control, but that is only part of the story of the rise in the insurance index. The other part is simply that there is more damage to cars and passengers.

There are many factors here. We have seen a rise in accident rates since the pandemic. There also is more damage due to climate-related events like hurricanes and flooding. Insofar as these factors lead to higher insurance premiums, this will be picked up in the CPI insurance index, since it simply measures the premiums that drivers pay.

This is in contrast to the auto insurance component of the Personal Consumption Expenditure Deflator (PCE). That component uses a net measure of the cost of auto insurance, which subtracts out the amount paid to customers in claims.

The insurance component in the PCE has a much lower weight in the index, just 0.57 percent, compared to 2.83 percent in the CPI. It also shows a considerably lower rate of inflation, rising just 6.6 percent over the last year.

What Should Count as Inflation?

This differing treatment raises an interesting conceptual issue about how we think about the CPI, inflation, and the cost of living. The CPI measures the change in the price of a fixed basket of goods and services. The basket changes every year, but it doesn’t pick up the effect of people switching, say from beef to chicken, in response to a change in relative prices, if beef prices rise more than chicken prices.

This issue has often been raised as a reason the CPI is inadequate as a measure of the cost of living, meaning that it overstates the true increase in the cost of living. In reality, this sort of “substitution” actually doesn’t matter much. An index that allows for the effect of substitution, like the PCE, shows a 0.2-0.3 pp lower rate of inflation. That can add up over time, but it doesn’t really qualitatively change our view of inflation.

The more important issue is how we deal with societal changes, as is happening with auto insurance. Suppose auto insurance costs more because more bad things are happening, like accidents or floods destroying cars. The PCE measure of insurance would not show this as an increase in the cost of living. The logic is that we are not actually paying a higher price for the same insurance, we are paying more because we are effectively getting more insurance.

This is in some sense true, but the only reason we need to buy more insurance is because drivers have become more reckless, or climate change is causing more damage. These changes have increased our cost of living, but in ways that may not be picked up in measured inflation.

To take a similar story, suppose crime in a neighborhood has exploded. Now people routinely get burglar alarms, put in extra locks and bars on windows, and get vicious dogs to discourage intruders. These are all higher costs that these people will incur, but none of them are included in the CPI or any other inflation measure.

Healthcare presents similar problems. Our inflation indexes measure the cost of specific treatments. But we don’t actually value the treatments — most of us would probably be happy never having to see the doctor – we value our health.

When a new disease appears, like Covid in 2020 or AIDS in the 1980s, the cost of treatment for the new disease is not factored into the inflation indexes. In fact, when the cost of a treatment declines, as when a drug goes off patent and the availability of generics drive down the price, the new disease has the effect of lowering the measured rate of inflation.

To my view, the best way to measure the cost of healthcare in an inflation index is to measure what we pay and simply deduct it from our disposable income. We have separate measures to evaluate health. People’s health may improve because they eat better, exercise more, or have a healthier environment. These outcomes imply an improvement in living standards in most people’s book even if we are not getting more drugs, tests, or medical procedures.

We also have problems that items become necessities, but the associated spending is not picked up in the CPI or other inflation measures. The Internet is great but try getting by without it. It really is necessary now to be on-line to be able to get access to a wide swath of information, much of which used to be available through other channels. (Have you seen a phone book lately?).

However, the cost of monthly Internet access, or the device needed to get on the Internet (phone or computer), does not appear as increase in the cost of living in our inflation indexes. There are many other items that fall into the same category. A car could be considered a luxury for most people 70 years ago. Now that many cities are pretty much designed around cars, it would be very difficult to get around without one.

Anyhow, this is a long way of saying that the cost of living can be a difficult concept. The CPI’s treatment of car insurance provides an interesting window on the issue. This measure is one way in which the effects of global warming will show up in the measured rate of inflation. Unfortunately, it is not the only way in which it will affect the cost-of-living.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We know that the media are busy covering the fact that President Biden is 81, but if they ever have a reporter, or maybe an intern, with a few spare minutes perhaps they could ask Donald Trump about his plans for cutting Social Security and Medicare. On Monday, Trump indicated his desire to cut these programs, saying on a television show:

“Tremendous bad management of entitlements. There’s tremendous amounts of things and numbers of things you can do. So I don’t necessarily agree with the statement ….” “First of all, there is a lot you can do in terms of entitlements, in terms of cutting, and in terms of, also, the theft and bad management of entitlements, …”

Later, his campaign referred reporters to a post that they had made on Twitter:

“If you losers didn’t cut his answer short, you would know President Trump was talking about cutting waste,”

As is common for Trump, his statement is not very coherent, but since the media practice affirmative action for the lazy sons of billionaires, that fact will likely not get much attention. But he does seem to be talking about cutting Social Security and Medicare benefits.

But let’s follow the path suggested by his campaign. Trump wants to eliminate waste. It would be good if the media could press Trump on what waste he sees in these programs.

In the case of Social Security, the administrative costs of the program come to less than 0.4 percent of the benefits that are paid out each year. This is around one-thirtieth of the fees that private sector 401(k)s charge.

But let’s say that Trump can find waste that he somehow overlooked in his first term, how much can he hope to save, will he reduce administrative costs by a quarter, by a third, by half? In that incredibly optimistic scenario, he would reduce the cost of the program by 0.2 percent. That would barely affect any of the numbers in the Social Security projections.

What about the “theft?” Well again, one has to wonder why he let this “theft” go unchallenged in his four years in the White House, but it would be good if Trump could give us some idea of what sort of theft he has in mind. Otherwise, we might think this is just like his tens of thousands of dead people voting in Georgia, or his 30,000 sq foot condo that is actually 10,000 sq feet, in other words, a complete figment of Trump’s imagination.

We do know that many people have sought to find theft in the Social Security program. In 2013, the Washington Post famously ran a huge front page article, that also took up the entire back page, which revealed that the program had paid 0.006 percent of its benefits over the prior three years to dead people. According to the article, roughly half of this money was repaid. It seems that the main issue was that family members often did not report the death of a beneficiary immediately and may have received a check or two after the person’s death, something that is easily imaginable in the era of direct deposit.

But let’s suppose that Trump’s vigilance can reduce the amount lost in payments to dead people by 50 percent, or 0.0015 percent of total payments. That would not go far towards reducing the program’s costs, but on the plus side the impact would be so small we wouldn’t have to change any of the numbers in the Trustees projections.

The prospect for savings is not much better on the Medicare side. Here it is worth noting that cost projections have come down hugely over the last quarter century and especially since the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Healthcare spending has largely leveled off as a share of GDP and even fallen somewhat in the last few years.

Perhaps Donald Trump thinks he has some magic wand that will reduce Medicare costs further. The media should treat Trump like a serious candidate and ask him what his trick is, and why he didn’t use it in his first term in office.

Medicare and Social Security are really big deals. There are more than 60 million beneficiaries of both programs and tens of millions more people expect to be receiving these benefits in the next ten or fifteen years. If Donald Trump wants to cut these programs people have a right to know.

We all know it’s very important that Joe Biden is 81, but maybe the media could shift its focus for just a few minutes to tell people about Donald Trump’s plans for Social Security and Medicare. Voters should be able to know before they cast their votes.

We know that the media are busy covering the fact that President Biden is 81, but if they ever have a reporter, or maybe an intern, with a few spare minutes perhaps they could ask Donald Trump about his plans for cutting Social Security and Medicare. On Monday, Trump indicated his desire to cut these programs, saying on a television show:

“Tremendous bad management of entitlements. There’s tremendous amounts of things and numbers of things you can do. So I don’t necessarily agree with the statement ….” “First of all, there is a lot you can do in terms of entitlements, in terms of cutting, and in terms of, also, the theft and bad management of entitlements, …”

Later, his campaign referred reporters to a post that they had made on Twitter:

“If you losers didn’t cut his answer short, you would know President Trump was talking about cutting waste,”

As is common for Trump, his statement is not very coherent, but since the media practice affirmative action for the lazy sons of billionaires, that fact will likely not get much attention. But he does seem to be talking about cutting Social Security and Medicare benefits.

But let’s follow the path suggested by his campaign. Trump wants to eliminate waste. It would be good if the media could press Trump on what waste he sees in these programs.

In the case of Social Security, the administrative costs of the program come to less than 0.4 percent of the benefits that are paid out each year. This is around one-thirtieth of the fees that private sector 401(k)s charge.

But let’s say that Trump can find waste that he somehow overlooked in his first term, how much can he hope to save, will he reduce administrative costs by a quarter, by a third, by half? In that incredibly optimistic scenario, he would reduce the cost of the program by 0.2 percent. That would barely affect any of the numbers in the Social Security projections.

What about the “theft?” Well again, one has to wonder why he let this “theft” go unchallenged in his four years in the White House, but it would be good if Trump could give us some idea of what sort of theft he has in mind. Otherwise, we might think this is just like his tens of thousands of dead people voting in Georgia, or his 30,000 sq foot condo that is actually 10,000 sq feet, in other words, a complete figment of Trump’s imagination.

We do know that many people have sought to find theft in the Social Security program. In 2013, the Washington Post famously ran a huge front page article, that also took up the entire back page, which revealed that the program had paid 0.006 percent of its benefits over the prior three years to dead people. According to the article, roughly half of this money was repaid. It seems that the main issue was that family members often did not report the death of a beneficiary immediately and may have received a check or two after the person’s death, something that is easily imaginable in the era of direct deposit.

But let’s suppose that Trump’s vigilance can reduce the amount lost in payments to dead people by 50 percent, or 0.0015 percent of total payments. That would not go far towards reducing the program’s costs, but on the plus side the impact would be so small we wouldn’t have to change any of the numbers in the Trustees projections.

The prospect for savings is not much better on the Medicare side. Here it is worth noting that cost projections have come down hugely over the last quarter century and especially since the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Healthcare spending has largely leveled off as a share of GDP and even fallen somewhat in the last few years.

Perhaps Donald Trump thinks he has some magic wand that will reduce Medicare costs further. The media should treat Trump like a serious candidate and ask him what his trick is, and why he didn’t use it in his first term in office.

Medicare and Social Security are really big deals. There are more than 60 million beneficiaries of both programs and tens of millions more people expect to be receiving these benefits in the next ten or fifteen years. If Donald Trump wants to cut these programs people have a right to know.

We all know it’s very important that Joe Biden is 81, but maybe the media could shift its focus for just a few minutes to tell people about Donald Trump’s plans for Social Security and Medicare. Voters should be able to know before they cast their votes.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This simple point was left out of a Washington Post article on the legal battle surrounding the Biden Administration’s efforts to negotiate lower prices for drugs purchased by Medicare. This point is important because the drug companies are definitely not trying to get the government out of the market, as the industry claims.

The industry is effectively insisting that the government is obligated to give it an unrestricted monopoly for the period of its patent duration. Also, since patent monopolies provide enormous incentives for corruption (they are equivalent to tariffs of many thousand percent, or even tens of thousands percent), drug companies often find ways to game the system and extend effective protection beyond the original patent life.

Anyhow, portraying this as a situation where the industry wants the free market and the Biden administration wants government intervention is 180 degrees at odds with reality. The industry wants very strong government intervention so that it can make big profits.

It’s also worth noting that the amount of money at stake here is potentially enormous. We will spend well over $600 billion this year on drugs. These drugs would likely cost less than $100 billion in a free market. The difference of $500 billion is more than eight times as large as President Biden’s requested funding for Ukraine.

This simple point was left out of a Washington Post article on the legal battle surrounding the Biden Administration’s efforts to negotiate lower prices for drugs purchased by Medicare. This point is important because the drug companies are definitely not trying to get the government out of the market, as the industry claims.

The industry is effectively insisting that the government is obligated to give it an unrestricted monopoly for the period of its patent duration. Also, since patent monopolies provide enormous incentives for corruption (they are equivalent to tariffs of many thousand percent, or even tens of thousands percent), drug companies often find ways to game the system and extend effective protection beyond the original patent life.

Anyhow, portraying this as a situation where the industry wants the free market and the Biden administration wants government intervention is 180 degrees at odds with reality. The industry wants very strong government intervention so that it can make big profits.

It’s also worth noting that the amount of money at stake here is potentially enormous. We will spend well over $600 billion this year on drugs. These drugs would likely cost less than $100 billion in a free market. The difference of $500 billion is more than eight times as large as President Biden’s requested funding for Ukraine.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There have been lots of reports in the media about China’s economic problems in recent months. Most of these pieces imply that it is facing some imminent disaster.

I will claim no special expertise on China, and it certainly looks like its government is pursuing some seriously wrongheaded policies, but it’s pretty difficult to see the disaster story in any publicly available data.

At the most basic level, most projections show its economy continuing to grow at a very healthy pace for the foreseeable future. Nonetheless, the coverage is almost exclusively negative.

For example, this New York Times piece noted China’s projection for 5.0 percent GDP growth in 2024 with the headline “Xi Sticks to His Vision for China’s Rise Even as Growth Slows.” China’s growth projections, as well as its official statistics, should be taken with a grain of salt. Nonetheless, few doubt that the picture shown by government data, of an extremely rapidly growing economy over the last four and half decades, is basically right.

But suppose we don’t want to take China’s projections for 2024 and instead turn to the I.M.F. as a more neutral source. The most recent projections from the I.M.F. show China’s economy growing 4.2 percent in 2024. Its growth is projected to remain above 4.0 percent for the following two years, and then fall somewhat below 4.0 percent for the last two years of its projection period.

Is this an economy in crisis? Well, it is undoubtedly slower than the near double-digit growth rates its economy chalked up for much of the period between 1980 and 2020, but it hardly seems like a crisis.

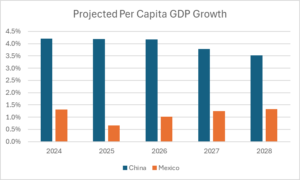

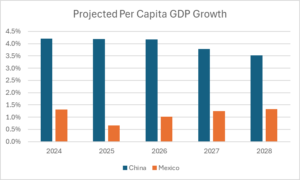

To see this point, we can compare the projected growth for China with the projected growth over this period for Mexico, a country with a nearly identical level of per capita income. This is shown below.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, Mexico is projected to have per capita income growth over this period averaging just over 1.0 percent annually, less than a third of China’s pace. (I have used per capita GDP to adjust for the fact that Mexico still has a growing population whereas China’s is declining slightly. Per capita GDP is a better gauge of living standards.) If we are to believe that China’s economy is facing some sort of crisis, then what do we think about an economy that is growing at less than a third of its pace?

It is also worth noting that, by this purchasing power parity measure, China’s economy is already considerably larger than the U.S. economy. It was 22.0 percent larger last year (24.0 percent including Hong Kong.) With the more rapid projected growth rate, it will be 34.0 percent larger by 2028.

This gap is worth noting when thinking about how best to deal with China. Those who think we can spend the country into the ground with a major military buildup need to check their arithmetic. (The Soviet economy peaked at roughly 60 percent of the size of the U.S. economy.)

The U.S. has differences with China in many areas, but both countries will fare much better if they look for areas for cooperation, like healthcare and climate, rather than confrontation. President Biden seemed to acknowledge this in his State of the Union address. It will be good if he follows through.

There have been lots of reports in the media about China’s economic problems in recent months. Most of these pieces imply that it is facing some imminent disaster.

I will claim no special expertise on China, and it certainly looks like its government is pursuing some seriously wrongheaded policies, but it’s pretty difficult to see the disaster story in any publicly available data.

At the most basic level, most projections show its economy continuing to grow at a very healthy pace for the foreseeable future. Nonetheless, the coverage is almost exclusively negative.

For example, this New York Times piece noted China’s projection for 5.0 percent GDP growth in 2024 with the headline “Xi Sticks to His Vision for China’s Rise Even as Growth Slows.” China’s growth projections, as well as its official statistics, should be taken with a grain of salt. Nonetheless, few doubt that the picture shown by government data, of an extremely rapidly growing economy over the last four and half decades, is basically right.

But suppose we don’t want to take China’s projections for 2024 and instead turn to the I.M.F. as a more neutral source. The most recent projections from the I.M.F. show China’s economy growing 4.2 percent in 2024. Its growth is projected to remain above 4.0 percent for the following two years, and then fall somewhat below 4.0 percent for the last two years of its projection period.

Is this an economy in crisis? Well, it is undoubtedly slower than the near double-digit growth rates its economy chalked up for much of the period between 1980 and 2020, but it hardly seems like a crisis.

To see this point, we can compare the projected growth for China with the projected growth over this period for Mexico, a country with a nearly identical level of per capita income. This is shown below.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, Mexico is projected to have per capita income growth over this period averaging just over 1.0 percent annually, less than a third of China’s pace. (I have used per capita GDP to adjust for the fact that Mexico still has a growing population whereas China’s is declining slightly. Per capita GDP is a better gauge of living standards.) If we are to believe that China’s economy is facing some sort of crisis, then what do we think about an economy that is growing at less than a third of its pace?

It is also worth noting that, by this purchasing power parity measure, China’s economy is already considerably larger than the U.S. economy. It was 22.0 percent larger last year (24.0 percent including Hong Kong.) With the more rapid projected growth rate, it will be 34.0 percent larger by 2028.

This gap is worth noting when thinking about how best to deal with China. Those who think we can spend the country into the ground with a major military buildup need to check their arithmetic. (The Soviet economy peaked at roughly 60 percent of the size of the U.S. economy.)

The U.S. has differences with China in many areas, but both countries will fare much better if they look for areas for cooperation, like healthcare and climate, rather than confrontation. President Biden seemed to acknowledge this in his State of the Union address. It will be good if he follows through.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Peter Coy used his column yesterday to beg President Biden not to use the term “greedflation” to explain the runup in inflation since the pandemic. I am sympathetic to much of his argument, most importantly, the idea that corporations suddenly turned greedy is a bit far out.

As Coy notes, corporations are always greedy. The real question is whether something unusual was going on with corporate profits in the pandemic. There clearly was an increase in profit margins in the pandemic. This was largely due to real shortages created by supply chain problems worldwide.

We can say this with a high degree of certainty because inflation was a worldwide story. This means that the idea that it was due to Biden’s “excessive” stimulus is silly.

While the U.S. is a huge part of the world economy, higher demand here could at most only explain a small fraction of the inflation in countries like the U.K. and Germany. The fact that their inflation has been similar to U.S. inflation since the pandemic, undermines the idea that Biden’s recovery package was the main factor in the U.S. inflation surge.

I have made this argument before and been told that people don’t care about inflation in the U.K. and Germany, they care about inflation here. That’s fine, but as an economist I’m trying to explain causation.

Any fool can look out over the horizon and see the earth is flat, the curvature of the planet is not generally visible in our range of vision. But we know the earth is in fact round, and no serious person is going to insist it is flat.

Similarly, we know inflation was a worldwide phenomenon due to the pandemic. If people want to yell at Biden over it, that is their right, but let’s not pretend that complaint is based in reality.

But let’s get back to “greedflation,” or “sellers’ inflation” the term used by Isabella Weber, the most prominent academic proponent of this view. There can be little doubt that there was a big shift to profits in the pandemic. Here’s the picture on the profit share of corporate income.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations, see text.

It goes from just under 25.0 percent to a peak of 28.0 percent in the second quarter of 2021. (This calculation is corporate net operating surplus, NIPA Table 1.14, line 8, divided by employee compensation, line 4, plus line 8.) However, since that peak the profit share has shifted down somewhat to 25.7 percent in the third quarter of last year, the most recent quarter for which we have data. This implies that further rises in profit shares have not contributed to inflation in the last two and a half years, but we are still seeing a disproportionate share of national income going to profit. Corporations are still keeping more than a quarter of their pandemic windfall.

I have included a second line that shows a somewhat less optimistic picture from the standpoint of those who don’t want to see corporations pocket everything. This line subtracts out the profits reported by Federal Reserve Banks (NIPA Table 6.16D, Line 11). These profits are refunded to the Treasury and should not be viewed as part of corporate profits.

Making this subtraction gives a slightly different path of profits over the course of the pandemic. Profits go from 24.6 percent of income in the fourth quarter of 2019 to a peak of 27.3 percent in the second quarter of 2021. This implies a similar but somewhat smaller runup than what is shown without this adjustment.

But we get a very different picture on the other side. The Fed banks are now losing money (short story, they were nailed by the rise in interest rates). This means that their losses are now being subtracted from the profits earned by the corporate sector, causing the published number to be somewhat lower than is actually the case.

Using this adjustment, corporate profits stood at 26.3 percent of income in the most recent quarter. This implies that corporations are still pocketing more than 60 percent of their pandemic dividend.

This still raises the question of whether corporations were taking advantage of their market power to push up profit margins. Keep in mind, it would not be surprising that there is a shift to profits when we see short-term shortages, that is pretty much a textbook outcome. The question is whether there was something more going on due to the greater monopolization of the U.S. economy than in past decades.

I am still agnostic on this point, but I will note three issues.

First, it seems clear that in a context of general inflation, corporations are better able to jack up their prices beyond the increases in costs they actually see. When all prices are rising 7-8 percent, it seems easier to raise your own prices by this amount, or maybe even more, whether or not that reflects actual costs.

The second point is that the rise in margins seems to be surviving beyond the supply-chain crisis. Perhaps we will see further reductions in margins going forward, but supply chains were pretty much back to normal by the start of 2023, but we still see inflated margins. This suggests something other than supply chains was the cause or at least that the effect is enduring beyond the period of actual shortages.

The third point is that inflation was worldwide. I have not looked at profit margins in other countries (perhaps someone else has these data), but we generally think that Europe has been somewhat more aggressive in enforcing anti-trust rules than the U.S. If profit shares have increased everywhere by similar amounts, that would argue against the idea that the issue was excessive monopolization in the U.S.

In any case, the data are clear, corporations are taking a larger share of the pie now than before the pandemic. Go nail the bastards, President Biden!

Peter Coy used his column yesterday to beg President Biden not to use the term “greedflation” to explain the runup in inflation since the pandemic. I am sympathetic to much of his argument, most importantly, the idea that corporations suddenly turned greedy is a bit far out.

As Coy notes, corporations are always greedy. The real question is whether something unusual was going on with corporate profits in the pandemic. There clearly was an increase in profit margins in the pandemic. This was largely due to real shortages created by supply chain problems worldwide.

We can say this with a high degree of certainty because inflation was a worldwide story. This means that the idea that it was due to Biden’s “excessive” stimulus is silly.

While the U.S. is a huge part of the world economy, higher demand here could at most only explain a small fraction of the inflation in countries like the U.K. and Germany. The fact that their inflation has been similar to U.S. inflation since the pandemic, undermines the idea that Biden’s recovery package was the main factor in the U.S. inflation surge.

I have made this argument before and been told that people don’t care about inflation in the U.K. and Germany, they care about inflation here. That’s fine, but as an economist I’m trying to explain causation.

Any fool can look out over the horizon and see the earth is flat, the curvature of the planet is not generally visible in our range of vision. But we know the earth is in fact round, and no serious person is going to insist it is flat.

Similarly, we know inflation was a worldwide phenomenon due to the pandemic. If people want to yell at Biden over it, that is their right, but let’s not pretend that complaint is based in reality.

But let’s get back to “greedflation,” or “sellers’ inflation” the term used by Isabella Weber, the most prominent academic proponent of this view. There can be little doubt that there was a big shift to profits in the pandemic. Here’s the picture on the profit share of corporate income.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations, see text.

It goes from just under 25.0 percent to a peak of 28.0 percent in the second quarter of 2021. (This calculation is corporate net operating surplus, NIPA Table 1.14, line 8, divided by employee compensation, line 4, plus line 8.) However, since that peak the profit share has shifted down somewhat to 25.7 percent in the third quarter of last year, the most recent quarter for which we have data. This implies that further rises in profit shares have not contributed to inflation in the last two and a half years, but we are still seeing a disproportionate share of national income going to profit. Corporations are still keeping more than a quarter of their pandemic windfall.

I have included a second line that shows a somewhat less optimistic picture from the standpoint of those who don’t want to see corporations pocket everything. This line subtracts out the profits reported by Federal Reserve Banks (NIPA Table 6.16D, Line 11). These profits are refunded to the Treasury and should not be viewed as part of corporate profits.

Making this subtraction gives a slightly different path of profits over the course of the pandemic. Profits go from 24.6 percent of income in the fourth quarter of 2019 to a peak of 27.3 percent in the second quarter of 2021. This implies a similar but somewhat smaller runup than what is shown without this adjustment.

But we get a very different picture on the other side. The Fed banks are now losing money (short story, they were nailed by the rise in interest rates). This means that their losses are now being subtracted from the profits earned by the corporate sector, causing the published number to be somewhat lower than is actually the case.

Using this adjustment, corporate profits stood at 26.3 percent of income in the most recent quarter. This implies that corporations are still pocketing more than 60 percent of their pandemic dividend.

This still raises the question of whether corporations were taking advantage of their market power to push up profit margins. Keep in mind, it would not be surprising that there is a shift to profits when we see short-term shortages, that is pretty much a textbook outcome. The question is whether there was something more going on due to the greater monopolization of the U.S. economy than in past decades.

I am still agnostic on this point, but I will note three issues.

First, it seems clear that in a context of general inflation, corporations are better able to jack up their prices beyond the increases in costs they actually see. When all prices are rising 7-8 percent, it seems easier to raise your own prices by this amount, or maybe even more, whether or not that reflects actual costs.

The second point is that the rise in margins seems to be surviving beyond the supply-chain crisis. Perhaps we will see further reductions in margins going forward, but supply chains were pretty much back to normal by the start of 2023, but we still see inflated margins. This suggests something other than supply chains was the cause or at least that the effect is enduring beyond the period of actual shortages.

The third point is that inflation was worldwide. I have not looked at profit margins in other countries (perhaps someone else has these data), but we generally think that Europe has been somewhat more aggressive in enforcing anti-trust rules than the U.S. If profit shares have increased everywhere by similar amounts, that would argue against the idea that the issue was excessive monopolization in the U.S.

In any case, the data are clear, corporations are taking a larger share of the pie now than before the pandemic. Go nail the bastards, President Biden!

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Wall Street Journal is unhappy with the move by President Biden to go after “junk fees,” by setting up a task force to uncover abusive pricing. It complains that this will interfere with companies’ ability to set prices where they think best, and will lead them to offset junk fees with overall price increases.

While the ending of junk fees may lead to some increase in advertised prices, this is exactly the point. We want people to know what they are paying. It doesn’t do you any good to get a cheap airline seat and then find out you have to pay big bucks for your carry-on luggage, an in-flight soda, and even using the restroom.

In every economics class we teach students that we get the best market outcomes where everyone is fully informed. If you see a plane seat advertised as $200, it should actually be $200. Then you can compare it to the price other airlines are charging. No one wants to get out a calculator and figure out what the price will be with all the various extra fees, if they can even find out about them before they get on the plane.

What President Biden is doing might be popular, as the WSJ suggests, but it is also good economics. Scam runners might be angered, but fans of the free market should be applauding.

The Wall Street Journal is unhappy with the move by President Biden to go after “junk fees,” by setting up a task force to uncover abusive pricing. It complains that this will interfere with companies’ ability to set prices where they think best, and will lead them to offset junk fees with overall price increases.

While the ending of junk fees may lead to some increase in advertised prices, this is exactly the point. We want people to know what they are paying. It doesn’t do you any good to get a cheap airline seat and then find out you have to pay big bucks for your carry-on luggage, an in-flight soda, and even using the restroom.

In every economics class we teach students that we get the best market outcomes where everyone is fully informed. If you see a plane seat advertised as $200, it should actually be $200. Then you can compare it to the price other airlines are charging. No one wants to get out a calculator and figure out what the price will be with all the various extra fees, if they can even find out about them before they get on the plane.

What President Biden is doing might be popular, as the WSJ suggests, but it is also good economics. Scam runners might be angered, but fans of the free market should be applauding.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had a news quiz that included the results of a survey showing how much money people thought we had given to Ukraine. What is striking is not just that people were wrong, but rather they were insanely wrong. (Post readers thankfully did considerably better than the people responding to the poll.)

The first question asked people how much aid we gave to Ukraine measured as a share of GDP. The correct number is around 0.5 percent of GDP, or $140 billion. (I haven’t tried to add it up carefully, so I am taking the Post at its word here.) According to the Post, 46 percent of people answered that we had spent close to 10 percent of GDP, which would come to $2.8 trillion. The piece reported that 23 percent answered that we spent an amount that was more than 20 percent of GDP, or $5.6 trillion.

The second number asked how Ukraine spending compared to Social Security spending. Forty two percent said we spend about the same on Ukraine as on Social Security and 28 percent said 18 times more. We spend roughly $1.4 trillion a year on Social Security, which means that over the last two years we have spent close to 20 times as much on Social Security as on Ukraine.

No one can expect the average person to know with any precision how much money the government is spending on Ukraine or anything else. People have jobs. They don’t have time to go digging through budget documents to figure out where the government’s money is going. But we might expect that they would be somewhere in the ballpark, maybe off by a factor of two or three, but not a factor of 20 or 40.

If people believe that we are spending twenty times as much on Ukraine as is actually the case, what does it mean when they say they are opposed to aiding Ukraine? Are they opposed to giving Ukraine the amount of money that is actually on the table or are they opposing giving an amount that is twenty times as large, which absolutely no one is proposing?

Part of this story is that the politicians opposed to aiding Ukraine have reason to lie about the money being spent. To advance their case they would like people to believe that the money going to Ukraine is preventing the government from spending money on popular domestic items. For this reason, they are happy to talk about Ukraine aid as though it is twenty or even forty times larger than is actually the case.

However, part of the blame for this extreme ignorance can be laid at the doorstep of the media. They routinely refer to spending amounts in the billions or tens of billions of dollars, sums that are meaningless to almost everyone who sees them.

It would be a very simple matter to refer to these numbers as shares of the budget. For example, the $60 billion proposal current on the table is equal to approximately 0.9 percent of this year’s budget. If the media routinely reported budget numbers in a way that provided some context, it is less likely that we would find that the vast majority of the public overstates spending on Ukraine or other items by an order of magnitude.

For what it’s worth, people in the media do recognize this problem. However, for some reason they refuse to do anything to address it. I will also add that there are entirely legitimate reasons that people may oppose aid to Ukraine, however being 10 percent of GDP is not one of them.

The Washington Post had a news quiz that included the results of a survey showing how much money people thought we had given to Ukraine. What is striking is not just that people were wrong, but rather they were insanely wrong. (Post readers thankfully did considerably better than the people responding to the poll.)

The first question asked people how much aid we gave to Ukraine measured as a share of GDP. The correct number is around 0.5 percent of GDP, or $140 billion. (I haven’t tried to add it up carefully, so I am taking the Post at its word here.) According to the Post, 46 percent of people answered that we had spent close to 10 percent of GDP, which would come to $2.8 trillion. The piece reported that 23 percent answered that we spent an amount that was more than 20 percent of GDP, or $5.6 trillion.

The second number asked how Ukraine spending compared to Social Security spending. Forty two percent said we spend about the same on Ukraine as on Social Security and 28 percent said 18 times more. We spend roughly $1.4 trillion a year on Social Security, which means that over the last two years we have spent close to 20 times as much on Social Security as on Ukraine.

No one can expect the average person to know with any precision how much money the government is spending on Ukraine or anything else. People have jobs. They don’t have time to go digging through budget documents to figure out where the government’s money is going. But we might expect that they would be somewhere in the ballpark, maybe off by a factor of two or three, but not a factor of 20 or 40.

If people believe that we are spending twenty times as much on Ukraine as is actually the case, what does it mean when they say they are opposed to aiding Ukraine? Are they opposed to giving Ukraine the amount of money that is actually on the table or are they opposing giving an amount that is twenty times as large, which absolutely no one is proposing?

Part of this story is that the politicians opposed to aiding Ukraine have reason to lie about the money being spent. To advance their case they would like people to believe that the money going to Ukraine is preventing the government from spending money on popular domestic items. For this reason, they are happy to talk about Ukraine aid as though it is twenty or even forty times larger than is actually the case.

However, part of the blame for this extreme ignorance can be laid at the doorstep of the media. They routinely refer to spending amounts in the billions or tens of billions of dollars, sums that are meaningless to almost everyone who sees them.

It would be a very simple matter to refer to these numbers as shares of the budget. For example, the $60 billion proposal current on the table is equal to approximately 0.9 percent of this year’s budget. If the media routinely reported budget numbers in a way that provided some context, it is less likely that we would find that the vast majority of the public overstates spending on Ukraine or other items by an order of magnitude.

For what it’s worth, people in the media do recognize this problem. However, for some reason they refuse to do anything to address it. I will also add that there are entirely legitimate reasons that people may oppose aid to Ukraine, however being 10 percent of GDP is not one of them.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had a piece on the tax code changes that will take effect next year unless Congress acts to extend current provisions. One of the items on this list is an increase in the amount of wealth exempted from the estate tax.

The piece lists the amount currently exempted as $13.6 million, with the possibility it will revert back to its pre-Trump level of $5 million (adjusted somewhat higher for inflation) if the Trump provision is not extended. It is important to point out that this is the exemption for a single individual. A couple would be able to pass on $27.2 million to their heirs without paying any tax whatsoever.

This tax applies to less than 2,000 estates a year, less than 0.1 percent of all estates. Even with the $5 million cutoff only around 5,000 estates paid the tax.

It is also important to recognize that the tax is marginal — it only applies to wealth above the cutoff. This means for example, that a couple with an estate of $27.5 million would only pay the 40 percent tax on the $300,000 above the cutoff. In this case the heirs would face a tax liability of $120,000, less than 0.5 percent of the estate.

The New York Times had a piece on the tax code changes that will take effect next year unless Congress acts to extend current provisions. One of the items on this list is an increase in the amount of wealth exempted from the estate tax.

The piece lists the amount currently exempted as $13.6 million, with the possibility it will revert back to its pre-Trump level of $5 million (adjusted somewhat higher for inflation) if the Trump provision is not extended. It is important to point out that this is the exemption for a single individual. A couple would be able to pass on $27.2 million to their heirs without paying any tax whatsoever.

This tax applies to less than 2,000 estates a year, less than 0.1 percent of all estates. Even with the $5 million cutoff only around 5,000 estates paid the tax.

It is also important to recognize that the tax is marginal — it only applies to wealth above the cutoff. This means for example, that a couple with an estate of $27.5 million would only pay the 40 percent tax on the $300,000 above the cutoff. In this case the heirs would face a tax liability of $120,000, less than 0.5 percent of the estate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is effectively what the state of Texas and Florida are arguing before the Supreme Court this week. This argument goes under the guise of whether states can prohibit social media companies from banning material based on politics. However, since much of Republican politics these days involves promulgating lies, like the “Biden family” Ukraine bribery story, the Texas and Florida law could arguably mean that the state could require Facebook and other social media sites to spread lies.

There is a lot of tortured reasoning around the major social media platforms these days. The Texas and Florida laws are justified by saying these platforms are essentially common carriers, like a phone company.

That one seems pretty hard to justify. In principle at least, a phone company would have no control over, or even knowledge of, the content of phone calls. This would make it absurd for a state government to try to dictate what sort of calls could or could not be made over a telephone network.

Social media platforms do have knowledge of the material that gets posted on their sites. And in fact they make conscious decisions, or at least have algorithms that decide for them, whether to leave up a post, boost it so that it is seen by a wide audience, or remove it altogether.

The social media companies arguing against the Florida and Texas laws say that they have a First Amendment right to decide what material they want to promote and what material they want to exclude, just like a print or broadcast outlet. However, there is an important difference between the factors that print and broadcast outlets must consider in transmitting and promoting content and what social media sites need to consider.

Modifying Section 230

Print and broadcast outlets can be sued for defamation for transmitting material that is false and harmful to individuals or organizations. Social media sites do not have this concern because they are protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

This means that not only are social media companies not liable for spreading defamatory material, they actually can profit from it. This is not only the case for big political lies. If some racist decides to buy ads on Facebook or Twitter falsely saying that they got food poisoning at a Black-owned restaurant, Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk get to pocket the cash.

The restaurant owner could sue the person who took out the ad, if they can find them (ads can be posted under phony names), but Facebook and Twitter would just hold up their Section 230 immunity and walk away with the cash. The same story applies to posts on these sites. These can also generate profits for Mr. Zuckerberg or Mr. Musk, since defamatory material may increase views and make advertising more valuable.

The ostensible rationale for Section 230 was that we want social media companies to be able to moderate their sites for pornographic material or posts that seek to incite violence, without fear of being sued. There is also the argument that a major social media platform can’t possibly monitor all of the hundreds of millions, or even billions, of posts that go up every day.

But removing protections against defamation suits does not in any way interfere with the first goal. Facebook or Twitter should not have to worry about being sued for defamation because they remove child pornography.

As far as the second point, while it is true that these sites cannot monitor every post as it goes up, they could respond to takedown notices that come from individuals or organizations claiming they have been defamed. There is an obvious model here. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act requires that companies remove material that infringes on copyright, after they have been notified by the copyright holder or their agent. If they remove the material in a timely manner, they are protected against a lawsuit. Alternatively, they may determine that the material is not infringing and leave it up.

We can have a similar process with allegedly defamatory material, where the person or organization claiming defamation has to spell out exactly how the material is defamatory. The site then has the option to either take the material down, or leave it posted and risk a defamation suit.

This would effectively be treating social media sites like print or broadcast media. These outlets must take responsibility for the material they transmit to their audience, even if it comes from third parties. (Fox paid $787 million to Dominion as a result of a lawsuit largely over statements by guests on Fox shows.) There is not an obvious reason why CNN can be sued for carrying an ad falsely claiming that a prominent person is a pedophile, but Twitter and Facebook get to pocket the cash with impunity.

We can also structure this sort of change in Section 230 in a way that favors smaller sites. We can leave the current rules for Section 230 in place for sites that don’t sell ads or personal information. Sites that support themselves by subscriptions or donations could continue to operate as they do now.

This would help to counteract the network effects that tend to push people towards the biggest sites. After all, if Facebook and Twitter were each just one of a hundred social media sites that people used to post their thoughts, no one would especially care what posts they choose to amplify or remove. If users didn’t like their editorial choices, they would just opt for a different one, just as they do now with newspapers or television stations.

It is only because these social media sites have such a huge share of the market that their decisions take on so much importance. If we can restructure Section 230 in a way that downsizes these giants, it will go far towards ending the problem.

Modifying Section 230 won’t fix all the problems with social media, but it does remove an obvious asymmetry in the law. As it now stands, print and broadcast outlets can get sued for carrying defamatory material, but social media sites cannot. This situation does not make sense and should be changed.

That is effectively what the state of Texas and Florida are arguing before the Supreme Court this week. This argument goes under the guise of whether states can prohibit social media companies from banning material based on politics. However, since much of Republican politics these days involves promulgating lies, like the “Biden family” Ukraine bribery story, the Texas and Florida law could arguably mean that the state could require Facebook and other social media sites to spread lies.

There is a lot of tortured reasoning around the major social media platforms these days. The Texas and Florida laws are justified by saying these platforms are essentially common carriers, like a phone company.

That one seems pretty hard to justify. In principle at least, a phone company would have no control over, or even knowledge of, the content of phone calls. This would make it absurd for a state government to try to dictate what sort of calls could or could not be made over a telephone network.

Social media platforms do have knowledge of the material that gets posted on their sites. And in fact they make conscious decisions, or at least have algorithms that decide for them, whether to leave up a post, boost it so that it is seen by a wide audience, or remove it altogether.

The social media companies arguing against the Florida and Texas laws say that they have a First Amendment right to decide what material they want to promote and what material they want to exclude, just like a print or broadcast outlet. However, there is an important difference between the factors that print and broadcast outlets must consider in transmitting and promoting content and what social media sites need to consider.

Modifying Section 230

Print and broadcast outlets can be sued for defamation for transmitting material that is false and harmful to individuals or organizations. Social media sites do not have this concern because they are protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

This means that not only are social media companies not liable for spreading defamatory material, they actually can profit from it. This is not only the case for big political lies. If some racist decides to buy ads on Facebook or Twitter falsely saying that they got food poisoning at a Black-owned restaurant, Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk get to pocket the cash.

The restaurant owner could sue the person who took out the ad, if they can find them (ads can be posted under phony names), but Facebook and Twitter would just hold up their Section 230 immunity and walk away with the cash. The same story applies to posts on these sites. These can also generate profits for Mr. Zuckerberg or Mr. Musk, since defamatory material may increase views and make advertising more valuable.

The ostensible rationale for Section 230 was that we want social media companies to be able to moderate their sites for pornographic material or posts that seek to incite violence, without fear of being sued. There is also the argument that a major social media platform can’t possibly monitor all of the hundreds of millions, or even billions, of posts that go up every day.

But removing protections against defamation suits does not in any way interfere with the first goal. Facebook or Twitter should not have to worry about being sued for defamation because they remove child pornography.

As far as the second point, while it is true that these sites cannot monitor every post as it goes up, they could respond to takedown notices that come from individuals or organizations claiming they have been defamed. There is an obvious model here. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act requires that companies remove material that infringes on copyright, after they have been notified by the copyright holder or their agent. If they remove the material in a timely manner, they are protected against a lawsuit. Alternatively, they may determine that the material is not infringing and leave it up.

We can have a similar process with allegedly defamatory material, where the person or organization claiming defamation has to spell out exactly how the material is defamatory. The site then has the option to either take the material down, or leave it posted and risk a defamation suit.

This would effectively be treating social media sites like print or broadcast media. These outlets must take responsibility for the material they transmit to their audience, even if it comes from third parties. (Fox paid $787 million to Dominion as a result of a lawsuit largely over statements by guests on Fox shows.) There is not an obvious reason why CNN can be sued for carrying an ad falsely claiming that a prominent person is a pedophile, but Twitter and Facebook get to pocket the cash with impunity.

We can also structure this sort of change in Section 230 in a way that favors smaller sites. We can leave the current rules for Section 230 in place for sites that don’t sell ads or personal information. Sites that support themselves by subscriptions or donations could continue to operate as they do now.

This would help to counteract the network effects that tend to push people towards the biggest sites. After all, if Facebook and Twitter were each just one of a hundred social media sites that people used to post their thoughts, no one would especially care what posts they choose to amplify or remove. If users didn’t like their editorial choices, they would just opt for a different one, just as they do now with newspapers or television stations.

It is only because these social media sites have such a huge share of the market that their decisions take on so much importance. If we can restructure Section 230 in a way that downsizes these giants, it will go far towards ending the problem.

Modifying Section 230 won’t fix all the problems with social media, but it does remove an obvious asymmetry in the law. As it now stands, print and broadcast outlets can get sued for carrying defamatory material, but social media sites cannot. This situation does not make sense and should be changed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión