July 31, 2024

In this edition of Sanctions Watch, covering July 2024:

- “Doha 3” meeting sees calls to ease Afghanistan’s economic isolation, but no concrete action;

- Cuba now faces a “war-time economy” as sanctions-fueled crisis continues to spiral;

- Iran elects reformist keen to dialogue over US sanctions, but White House rebuffs;

- Expert from now-defunct Security Council panel critiques North Korea sanctions policy;

- US threatens new sanctions on China over alleged support for Russia

- Sanctions drive illicit Captagon trade in Syria, finds The Washington Post;

- Maduro’s reelection in Venezuela, contested, with US concerns likely to shape future sanctions;

- The Washington Post launches a new series on US “economic warfare,” and more.

Afghanistan (background)

The third UN-convened meeting on Afghanistan took place in Doha late last month, with the Taliban government taking part for the first time, after having been excluded from the first meeting, and refusing to attend the second. The Afghan government’s top priority was the lifting of economic sanctions and the unfreezing of central bank funds. While Western donor countries and segments of civil society criticized the talks, others have called for greater engagement. Georgetown professor and CEO of Gulf State Analytics Giorgio Cafiero writes that the Taliban is the de facto ruler of the country, and “Washington not recognizing the Taliban while imposing sanctions on Afghanistan is unlikely to change that.” Russia and China appear to be moving closer toward this approach — both are increasingly engaging with the country, and a Russian official suggested this month that the country was considering dropping its sanctions on the Taliban. The meeting did not produce major concrete outcomes, but reportedly set the stage for further dialogue.

Meanwhile, a new Council on Foreign Relations report notes:

Sanctions and the termination of significant development aid have crippled the Afghan economy. The revocation of the country’s central bank’s credentials halted all basic banking transactions and drastically restricted critical cash flow relied on by Afghan families for daily market activities. Furthermore, skyrocketing inflation has meant an over 50 percent increase in the price of goods from July 2021 to June 2022.

Read more:

- Russian Envoy to UN Hints Moscow Could Drop Sanctions on Taliban, AFP

- Report: Instability in Afghanistan, Council on Foreign Relations

- How to Engage with the Taliban, If You Have To, The New Humanitarian

Cuba (background)

The Cuban government has declared that it is in what amounts to a “war-time economy,” as the country’s dire, sanctions-fueled economic crisis continues to spiral. A raft of new measures aimed at addressing the crisis includes budget cuts; food price caps, including for the private sector; and restrictions on private sector use of US bank accounts (only recently permitted on the US side) to keep dollars on the island and prevent price gouging. The Cuban national statistics organization recently reported that, amid this humanitarian crisis, roughly 10 percent of the country’s entire population emigrated in just a two-year period.

On a recent Alliance for Cuba Engagement and Respect webinar exploring how US sanctions are a “root cause” of this unprecedented migration wave, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) urged President Biden to remove Cuba from the State Sponsors of Terrorism list, calling the designation “inappropriate.” Three UN independent human rights experts put out a statement with the same demand, highlighting its harmful impacts on the Cuban population and describing it as “contrary to fundamental principles of international law.” Similar calls were made this month by the California Labor Federation, which represents 2.3 million workers; the chair of the Justice and Peace Committee of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops; and at the Organization of American States by the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Colombia. The resident coordinator of the United Nations System in Cuba also condemned the designation, noting that it impedes the work of the United Nations on the island.

Also this month, leading embargo-advocate Senator Bob Menendez (D-NJ) announced that he would soon resign following his conviction for corruption.

Read more:

- Wayne S. Smith, Diplomat Who Resigned Over US Policy Toward Cuba, Dies at 91, The Washington Post

- Bob Menendez and Biden’s Cuba Policy, The American Prospect

- The Government of Cuba Declares Itself in a ‘War-Time Economy,’ El País

Iran (background)

On July 30, Masoud Pezeshkian was inaugurated as president of Iran following a July 5 run-off election that saw the moderate soundly defeat the hard-line candidate. Pezeshkian ran on a platform of reform, including promises to reengage in dialogue with the West in order to reduce the heavy toll of sanctions on the economy. When asked if they were open to restarting talks with the new Iranian president, the White House gave a categorical “no.” The policy director of the National Iranian American Council called this “a self-defeating position that must be revisited,” saying, “Refusing to talk with a reformist who campaigned on negotiations and easing sanctions doesn’t make sense for the national interest, and also has the added effect of making clear again that the US is a major part of the problem,” he noted. President-elect Pezeshkian later reiterated that he “remains ready for any kind of dialogue” despite the fact that “it was the US that first withdrew from the JCPOA [Iran nuclear deal] and then imposed the harshest sanctions on the Iranian nation.” Pezeshkian’s opponents in the elections had pointed to the US’s unilateral withdrawal from the deal as evidence that diplomacy with the US would not succeed, and it is unclear to what extent attempts to restart dialogue would have the Supreme Leader’s support.

Interviews by The New York Times prior to the election found that Iranian civilians were overwhelmingly concerned with the state of the economy: “After years of crippling U.S. sanctions that generated chronic inflation, made worse by Iran’s economic mismanagement and corruption, Iranians increasingly feel trapped in a downward economic spiral.” Economist and Iran sanctions expert Esfandyar Batmanghelidj noted that Pezeshkian could not confront the country’s economic troubles “without major improvements in Iran’s trade balance, fiscal position, or access to central bank reserves,” adding that, “In each of those areas, sanctions have tied the hands of Iranian policymakers.”

Read more:

- Iranians’ Demand for Their Leaders: Fix the Economy, The New York Times

- Iran’s President-Elect Says Ready for ‘Any Kind of Dialog’ for Sanctions Relief, Iran International

- United States Imposes Sanctions Targeting Iran’s Chemical Weapons Research and Development, US Department of State

North Korea (background)

According to the Bank of Korea, North Korea’s economy experienced its strongest year of growth in nearly a decade in 2023, following years of sanctions and COVID-induced contraction. The growth was credited to an increase in alleged arms transfers with Russia. Russia continues to deny US accusations that it is illegally transferring arms from North Korea. The allegations form part of a wider disagreement on the UN Security Council regarding North Korea policy, which came to a head earlier this year when Russia vetoed the extension of the mandate of the UN Panel of Experts tasked with monitoring North Korea sanctions. Efforts to establish a new UN monitoring mechanism outside of the Security Council have reportedly stalled.

In a wide-ranging interview with the Seoul-based NK News, Russian expert, and former member of the UN Panel of Experts, Georgy Toloraya outlined his critique of the evolution of the Security Council sanctions, including those that Russia had previously supported. Stressing his commitment to the underlying goal of nuclear nonproliferation, Toloraya argues that the Security Council erred in its 2016 expansion of restricted activities to include all activities tied to the development of ballistic missiles, and in its 2017 ban on North Koreans working overseas. He said that, to the detriment of the goal of disincentivizing nuclear arms, the United States pushed the Council toward a “hidden agenda of stiffening the regime of isolation and undermining the regime so that North Korea would collapse.”

Also this month, the Biden administration announced new sanctions on a dozen Chinese individuals and firms accused of supplying inputs for ballistic missiles, and Taiwan drafted plans to close loopholes that facilitate the transfer of oil from its ports to North Korea.

Read more:

- Russia Was Wrong to Endorse Wide-Ranging North Korea Sanctions: Russian Expert, NK News

- North Korea’s Economy Rebounds as Kim-Putin Ties Fuel Arms Trade, Bloomberg

- US Sanctions China-Based Network over Links to North Korea Space and Missile Programmes, South China Morning Post

- Taiwan Targets North Korean Oil Smuggling, Financial Times

Russia (background)

In a significant escalation of rhetoric, NATO explicitly accused China of being “a decisive enabler of Russia’s war against Ukraine,” warning of unspecified repercussions should this continue. China denies the accusation, which is based on reports of Chinese provision of software, computer chips, and other components that could be used to build weapons, but not of weapons themselves. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan reiterated NATO’s threats, hinting that the administration is considering sanctioning Chinese banks. The threats follow the expansion of secondary sanctions authorities last month, a move that has reportedly significantly impacted the Russian private sector by decreasing the willingness of Chinese banks to make or receive payments from Russia. In response, Russia and China are attempting to accelerate the development of digital payment systems that would be less susceptible to US sanctions.

Following last month’s agreement by the G7 to move forward with plans to seize the windfall profits of frozen Russian assets, Russia has warned that it is willing to retaliate against Western funds and properties that remain in Russia — while many Western companies have left or reduced operations in Russia since 2022, nearly $200 billion of assets from US and EU companies remain. Also this month, the UK imposed sanctions on 11 oil tankers with alleged Russian links, the US sanctioned two alleged Russian hackers, and Ukraine urged Hong Kong to take action against the extensive flow of prohibited chips to Russia.

Read more:

- For First Time, NATO Accuses China of Supplying Russia’s Attacks on Ukraine, The New York Times

- Russian Firms Face Mounting Payment Issues as Sanctions Bite, Bloomberg

- Western Companies Are Now Paying for Russia Sanctions, Foreign Policy

Syria (background)

An article published by The Washington Post this month (part of a new series on sanctions, see below) explores the profound and often unintended consequences of US sanctions on Syria. Namely, political and military elites seeking alternative sources of income following the imposition of sanctions turned to the production and sale of an amphetamine-like drug called Captagon, now one of the few-remaining booming industries in the country. “This is the stream of revenue on which they are relying in the face of sanctions pressure from us and from the European Union,” notes former US special envoy to Syria Joel Rayburn. According to Brown University professor Peter Andres, this turn to illicit activities is not unexpected; sanctions can “put the whole economy in an underworld.” As the article notes, “the targets of sanctions inevitably find ways to blunt their impact, often with painful consequences for ordinary citizens.” Meanwhile, “Assad is unshaken and apparently wealthier than ever.”

The piece also notes the severity of the country’s ongoing economic challenges, which are exacerbated by sanctions: “At least 12 million Syrians are now refugees or internally displaced, and 90 percent of the country’s citizens live in poverty. The country’s GDP fell from a prewar high of $252 billion to just $9 billion in 2021, according to World Bank estimates. The economy continues to shrink, as does the life expectancy for young Syrians.”

Also this month, eight EU member countries wrote a letter urging a reassessment of the bloc’s policy of politically isolating Syria and calling, among other things, for “an analysis of EU sanctions imposed on Syria to ensure they are penalizing regime officials and not the private sector.” Italy, one of the authors of the letter, also appointed an ambassador to Syria this month, the first G7 country to do so since ties were cut in 2011.

Read More:

- Sanctions Crushed Syria’s Elite. So They Built a Zombie Economy Fueled by Drugs., The Washington Post

- EU Countries Urge Revision of Bloc’s Policy on Syria, Deutsche Presse-Agentur

- Italy Appoints Ambassador to Syria to ‘Turn Spotlight’ on Country, Foreign Minister Says, Reuters

Venezuela (background)

Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro was elected to a third term late this month, according to preliminary results announced by the electoral council. The opposition, however, has also claimed victory, and the electoral council has yet to provide a detailed breakdown of the vote.

Secretary Blinken expressed “serious concerns” about the validity of the election, an indication of a contentious path ahead as the administration had previously signaled that it would “calibrate” its sanctions policy depending on the results of the election. While the country has partially recovered from the nadir of its economic crisis, economic conditions under sanctions remained a key electoral consideration. As CEPR’s Jake Johnston wrote in the run-up to the vote, sanctions “destabilized the electoral landscape.” Per Bloomberg:

The sanctions, imposed by the Trump administration as part of a strategy to weaken and unseat Maduro, accelerated a years-long drop in the production of oil, the nation’s lifeblood. Output is currently around 900,000 barrels of crude a day, less than a third of the 3 million barrels it produced daily in 1998, the year Maduro’s predecessor and mentor, Hugo Chavez, was first elected. Living conditions have sank [sic] along with it.

Some commentators have noted that, even if Maduro cannot offer the receipts proving his victory, ongoing — let alone expanded — sanctions on Venezuela would likely only make the situation worse, and would mostly harm the Venezuelan people.

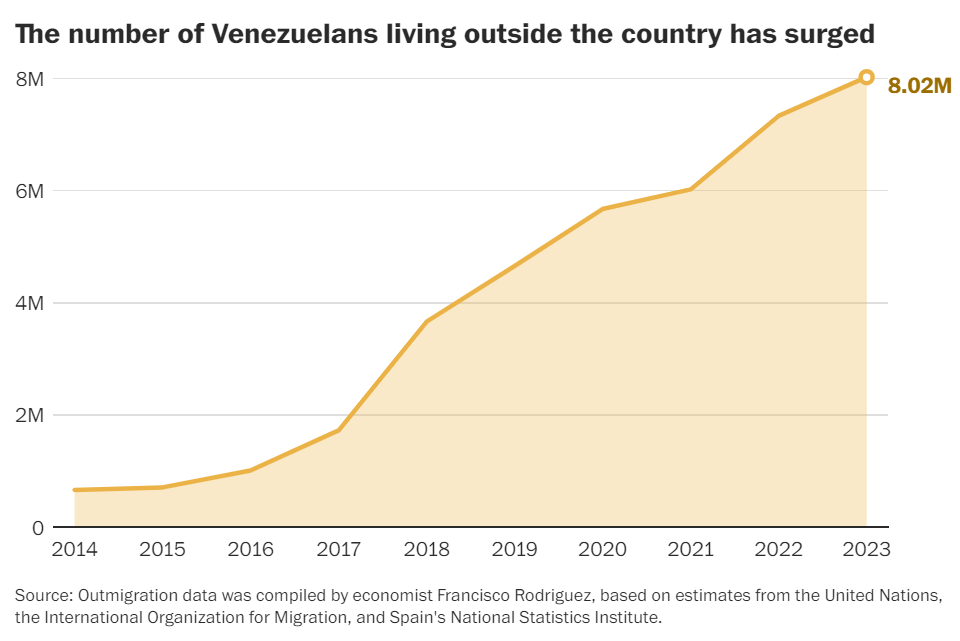

Also this month, The Washington Post published an in-depth examination of how sanctions have contributed to Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis and driven mass migration to the US, part of its new series on US sanctions (see below). The article reports that Trump administration officials were fully aware that the sanctions would broadly impact the civilian population, and in doing so drive people to leave the country. “I said [at the time] the sanctions were going to grind the Venezuelan economy into dust and have huge human consequences, one of which would be out-migration,” said one former Trump official. The article even cites John Bolton admitting that that was part of the intent: “That, to me, was a way to put pressure on the country.” In the event, the sanctions contributed to the largest peacetime economic contraction in modern history, roughly “three times as deep as the Great Depression in the United States,” and the emigration of over 7 million people. CEPR Senior Research Fellow Francisco Rodríguez is quoted in the article, saying, “[Venezuelans] left the country because the economy collapsed. And the economy collapsed partially because of sanctions. There is overwhelming evidence of that.”

Source: The Washington Post

Read more:

- Trump White House Was Warned Sanctions on Venezuela Could Fuel Migration, The Washington Post

- Ahead of Venezuela’s Election, What Do the Polls Really Show?, CEPR

- Treasury Sanctions Tren de Aragua as a Transnational Criminal Organization, US Department of Treasury

- US Appeals Court Vacates Ruling Favoring PDVSA Bondholders, Reuters

Other

This month, The Washington Post launched a groundbreaking new series on how the US has “unleashed economic warfare across the globe.” In their introductory piece, reporters Jeff Stein and Federica Cocca find that there is now an “almost reflexive use” of sanctions in “perpetual economic warfare,” regardless of their efficacy or consequences, which has “spawned a multibillion-dollar industry” of lobbyists, lawyers, and consultants in the US. Stein and Cocca find that 60 percent of all low-income countries now face US sanctions of some kind, with dramatic humanitarian consequences. As former Obama administration deputy national security advisor Ben Rhodes notes in the piece, “We don’t think about the collateral damage of sanctions the same way we think about the collateral damage of war. But we should.” The series also takes an in-depth look at how sanctions have harmed civilians in, and driven migration from, Syria and Venezuela.

Sharing the article, Rep. Chuy García (D-IL) said, “Sanctions shouldn’t be the US foreign policy tool of first resort. They wage economic warfare against civilians, while often reinforcing regime behaviors they seek to punish. We must review the effectiveness and harms of our sanctions policy.” Similarly, Rep. Greg Casar (D-TX) commented: “… broad US sanctions fuel poverty, hunger, & forced migration. We currently sanction *60% of poor countries.* Sanctions can no longer be our country’s ‘go-to’ policy. It’s time to prioritize diplomacy & more effective strategies instead.”

Pointing to the recent starvation deaths of Palestinian children, 11 UN independent human rights experts wrote a letter this month declaring that “Israel’s intentional and targeted starvation campaign against the Palestinian people is a form of genocidal violence and has resulted in famine across all of Gaza.” The letter came shortly after the publication of the latest Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) report, which found that 95 percent of the population of Gaza faces high levels of acute food insecurity. While defenders of Israel’s policy pointed to the fact that the IPC has not yet declared a full-blown famine in Gaza as evidence that fears were overblown, the New York Times notes: “many people may die before all the [IPC’s specific] criteria are met. Since the I.P.C. standards were developed in 2004, they have been used to identify only two famines: in Somalia in 2011, and in South Sudan in 2017. In Somalia, more than 100,000 people died before famine was officially declared.”

Also this month, the US imposed sanctions on a dozen individuals and entities from Malaysia, Singapore, and China accused of financial ties to Ansar Allah in Yemen. The White House is also reportedly considering designating the group a Foreign Terrorist Organization, on top of January’s Specially Designated Global Terrorist Group listing. US Special Envoy to Yemen Tim Lenderking euphemistically noted that this designation would come with humanitarian and economic “tradeoffs.” The Red Cross expressed concern about “additional measures that may have adverse impacts on affected populations and the provision of impartial humanitarian assistance.” According to ABC News, 80 percent of the country’s population is in need of humanitarian assistance, 20 million people are food insecure, and 4.5 million are internally displaced.

Read more:

- How Four US Presidents Unleashed Economic Warfare Across the Globe, The Washington Post

- UN Experts Declare Famine Has Spread Throughout Gaza Strip, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

- ‘Now There’s Barely Anything’: Gazans Describe Life on the Verge of Famine, The New York Times

- Red Sea Tensions Reach New High as US Weighs Terrorist Designation for Houthis, ABC News

- US Announces Sanctions on Israeli Settlers Over West Bank Violence, Al Jazeera

- EU Imposes Sanctions on Five Israeli Individuals and Three Entities, Reuters

- Australia Imposes Sanctions on Israeli Settlers, Al Jazeera

- Alleged Transnational Human Smuggler Indicted and Sanctioned in the United States and Arrested in Mexico, Department of Homeland Security

- US Sanctions More Chinese Officials for ‘Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity’ in Xinjiang, South China Morning Post

- US Treasury Sanctions Sierra Leone Man for Allegedly Smuggling Migrants Into the United States, Associated Press

- The Rule of Law is Made to be Broken, Al Jazeera

About Sanctions Watch

Economic sanctions have become one of the main tools of US foreign policy despite widespread evidence that they can cause severe harm to civilian populations (which may, in fact, be the point). Though now a defining feature of the global economic order, sanctions and their human costs receive relatively little attention in most US media outlets.

CEPR’s Sanctions Watch news bulletin aims to generate more awareness on the use and impact of sanctions through monthly round-ups of news and analysis on US sanctions policy.

Click here to see past editions of CEPR’s Sanctions Watch.