July 26, 2011

Catherine Rampell had a post last week declaring that “College is (Still) Worth It“. The piece is the latest in a series that she and her Economix blog colleague, David Leonhardt, have written on the financial benefits of college.

I agree with Rampell and Leonhardt that college is, on average, a good investment for the people who make it. But, Rampell and Leonhardt’s posts completely sidestep the key issue: why is it that when confronted with compelling evidence that college pays a big financial dividend, so many young people still don’t get a college degree?

Heather Boushey and I argue that the short answer is that for a surprising share of college graduates, the large price tag may actually not pay off.

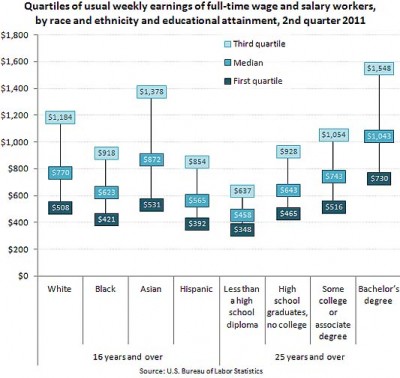

Rampell’s latest installment includes this nice graph of weekly earnings by worker characteristics, including educational attainment on the right-hand side:

For Rampell, the figure makes a slam-dunk case for the financial benefits of graduating from college. Here is her take on what the graph shows:

The median weekly earnings for college graduates are $1,043. Not bad, especially when you consider that the median weekly earnings for a high school graduate are $643.

What’s more impressive, though, is that even the economic underachievers among college graduates earn more than the typical high school grad: A college graduate at the 25th percentile makes $730 per week, which is still 13.5 percent more than the median high school grad.

But, other ways to read this graph can lead to a different conclusion. The figure also shows, for example, that something approaching half of college graduates (the figure doesn’t allow for too much precision) make less than the top 25 percent of high school graduates. And somewhere approaching half of high school graduates make more than the bottom 25 percent of college graduates.

In other words, after shelling out for four years of tuition, not to mention enduring four or more years of low or no earnings, perhaps 40 percent of college-educated workers make less than the top 25 percent of high school graduates.

This alternative reading of the figure helps to explain why many young people have not responded so enthusiastically to the “market signals” about college. On average, college pays off, but for a sizeable minority of college graduates, the arithmetic is not so convincing.

If you conclude that you might fall in the “below average” category, the graph in Rampell’s piece suggests that you might be better off skipping college, and saving yourself the direct and indirect costs, including student loans, which you’ll be responsible for paying off even if you don’t finish. (More than 40 percent of college enrollees do not finish within six years of starting.)

I’m not saying that blowing off college is the “right” thing to do. I am just saying that it is understandable that many young people would decide against seeking a college degree. Moreover, in a strictly financial sense, for a portion of college graduates, the decision to attend college may well have been the wrong one. (Of course, there are many non-financial reasons to attend college.)

Recent high school graduates already know that college graduates generally earn more than high school graduates. But, they also know that college is expensive, involves taking out loans, postponing earnings, maintaining a grade-point average, and making personal sacrifices. Recent high school graduates need help surmounting these very concrete barriers, not more information about how much better off they’ll be if they can only finish college.

This post originally appeared on John Schmitt’s blog, No Apparent Motive.