June 08, 2010

In a paper released earlier today, John Schmitt, Sarika Gupta, and I looked at the issue of incarceration in the United States. In 2008, more than 2.3 million people were behind bars in U.S. prisons and jails. This translates to a rate of 753 per 100,000 people, which is more than seven times higher than the median (102) in rich countries that make up the OECD. (Iceland has the lowest rate at 44, while Poland has the second-highest at 224.) This is also much higher than rates that we have seen in our own past. In 1980, when the U.S. incarceration rate was already at a historical high, it was 220 per 100,000 people.

This dramatic increase has not come cheaply: in 1982, state and local governments spent nearly $17 billion (in 2008 dollars) on corrections. In 2008, they spent just over $67 billion. (In fact, just the rise over this period in state-level expenditures on incarceration amounts to one-sixth of CBPP’s projected state budget shortfall in 2010.) What is going on?

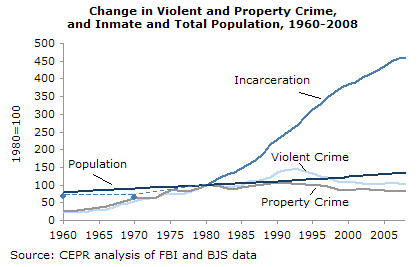

You might think that rising crime might be behind the big jump in incarceration. However, the data just don’t make the case. The graph below shows the change in violent and property crime along with the incarcerated population and the overall population, all indexed to their level in 1980. While both violent and property crime did increase until the early 1990s, from that point on, crime dropped off even as the incarceration rate continued its steady climb. If the incarceration rate were simply a function of crime, then it would have decreased as well.

On the other hand, could the higher incarceration rate be causing the drop in crime since the early 1990s? This does not appear to be the case either. Don Stemen of the Vera Institute for Justice conducted an extensive review of the existing literature in 2007 and came to this conclusion: “The most sophisticated analyses generally agree that increased incarceration rates have some effect on reducing crime, but the scope of that impact is limited: a 10 percent increase in incarceration is associated with a 2 to 4 percent drop in crime. Moreover, analysts are nearly unanimous in their conclusion that continued growth in incarceration will prevent considerably fewer, if any, crimes than past increases did and will cost taxpayers substantially more to achieve.”

Where does that leave us? All indications point to deliberate policy choices – a politically safe “tough on crime” approach created an inflexible legal framework that simply locked people up and kept them there longer.

We prefer a “smart on crime” approach. Mandatory minimum sentences, three strikes laws, and truth-in-sentencing laws have contributed substantially to the growing numbers of non-violent offenders in prisons and jails. Repealing these laws and reinstating greater judicial discretion would allow non-violent offenders to be sentenced to shorter terms or to serve in community corrections programs (such as parole or probation) in lieu of prison or jail. We estimate that if 50% of non-violent offenders were placed on probation or parole, $14.9 billion – about one quarter – could be shaved off the current state and local corrections budgets.