June 12, 2012

Many of the leading voices in economic policy debates are telling us that excess government spending, like that characteristic of Western European welfare states over the past sixty years, leads ultimately to rising interest rates. This happens, it is argued, because excessive government spending is likely to crowd out private investment and consumption. This will slow growth and lead to higher inflation.

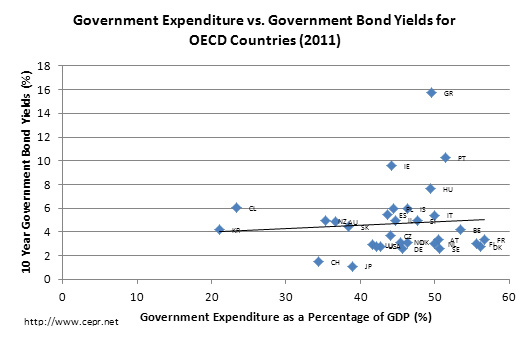

However, a cursory glance at recent data on government spending and the interest rates of government bonds reveals a different story. For 2011, we plotted government expenditure as a percentage of GDP versus the yields on ten-year government bonds for the OECD countries, and found a slight positive relationship between spending and interest rates, as is shown in the following figure.

While a small positive relationship appears to exist, as can be seen by the upward slope of the line of best fit in the chart above, regression analysis of bond yields and government expenditure showed that this relationship was not statistically significant. Any miniscule positive relationship can be attributed to a few countries with high government expenditure as share of GDP and high bond yields. These are the European economies of Greece, Portugal, and Ireland. While it is possible that government spending played a role in precipitating the current crisis in Greece, this is not the case for the other distressed economies. For instance, Ireland and Spain both ran budget surpluses in the years just before the recession. Noteworthy, also, are the many countries, such as France, Denmark, Finland, and Belgium, with high government expenditure and very low bond yields.

While a small positive relationship appears to exist, as can be seen by the upward slope of the line of best fit in the chart above, regression analysis of bond yields and government expenditure showed that this relationship was not statistically significant. Any miniscule positive relationship can be attributed to a few countries with high government expenditure as share of GDP and high bond yields. These are the European economies of Greece, Portugal, and Ireland. While it is possible that government spending played a role in precipitating the current crisis in Greece, this is not the case for the other distressed economies. For instance, Ireland and Spain both ran budget surpluses in the years just before the recession. Noteworthy, also, are the many countries, such as France, Denmark, Finland, and Belgium, with high government expenditure and very low bond yields.

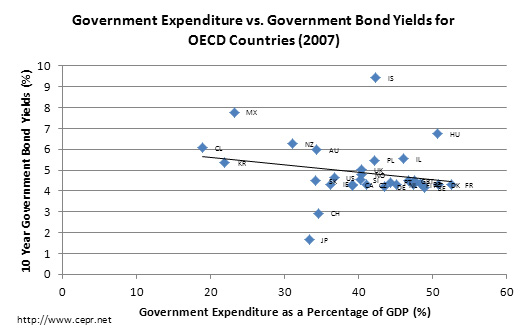

From the 2011 data, it is clear that, at best, a simple positive relationship makes up a very small part of the story. At worst, it appears that any positive relationship may in fact largely be the result of the recession, and not any underlying connection between excess government spending and interest rates. To control for the impact of the economic downturn, we plotted the same data for 2007. As is plain to see in the following figure, the positive relationship disappears.

In this case, a weak negative relationship appears to exist, as illustrated by the downward slope of the line fitting the data in the above chart. However, again, regression analysis of bond yields and government expenditure showed that this relationship was not statistically significant.

From our quick glance at the data, we can say, at the very least, that a simple positive relationship between government spending and interest rates in OECD countries does not exist. This is not to say that there is no possibility that a properly specified model may in fact demonstrate a positive relationship between these factors, but, on the surface, there is no clear evidence supporting the argument that high levels of government spending necessarily raise interest rates. Many countries have managed to sustain high levels of government spending for long periods of time and still maintain low interest rates.

* For 2011, the countries compared are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States.

** For 2007, the countries compared are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States