November 29, 2011

November 29, 2011 (Housing Market Monitor)

By Dean Baker

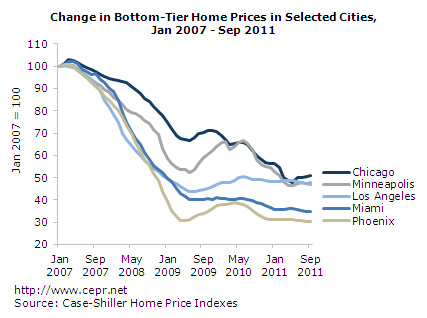

Homes in lower third of the Phoenix market now sell for 30 percent of their peaks.

The seasonally adjusted Case-Shiller 20-City index fell 0.6 percent in September, its fifth consecutive monthly decline. It has now fallen at a 4.1 percent annual rate over the last three months and is down by 3.6 percent from its year-ago level. The unadjusted index showed a similar picture, with the unadjusted 20-City index falling also by 0.6 percent and prices dropping in 17 of the 20 cities.

There is some question at this point as to whether it is more appropriate to use the seasonally adjusted data or the unadjusted data because of the large proportion of distress sales in the data (~25-30 percent). These sales would not follow normal seasonal patterns, so the seasonal adjustments would likely be inaccurate. However, at this point the share of distress sales in total sales has stabilized. Even if the seasonal adjustments may not be useful for this portion of the survey, they would provide a better measure for the remaining 70-75 percent of non-distress sales. For this reason, the seasonally adjusted data probably provide a better measure of price changes at this point.

The biggest price decline was in Atlanta, where the index fell by 4.1 percent in September. The rate of decline over the last three months has been 28.2 percent, pushing prices down by 9.8 percent from their year-ago levels. This price drop is driven primarily by homes in the bottom third of the market. House prices in this tier fell by 7.9 percent in September and have plunged at an incredible 53.2 percent annual rate in the last three months.

The next largest price declines were in Las Vegas (1.8 percent), Tampa (1.7 percent), Los Angeles (1.0 percent), and San Francisco (0.9 percent). Prices in Las Vegas have been falling at a 13.3 percent rate over the last three months, compared to a 9.6 percent rate in Tampa. The annual rate of decline over the last three months in Los Angeles has been 9.5 percent and in San Francisco 9.6 percent.

All four of these cities had substantial bubbles in their housing markets; however, the bubbles in Las Vegas and Tampa have deflated, with further price declines pushing prices below their trend path. Adjusted for inflation, house prices in Tampa are a few percentage points below their mid-90s level while prices in Las Vegas are almost 30 percent lower. Inflation-adjusted prices in San Francisco are still more than 30 percent higher than their mid-90s level, while prices in Los Angeles are more than 50 percent higher. By comparison, the real increase in rents since the mid-90s in these two cities has been 12 and 14 percent, respectively. This suggests that there is room for substantial further declines in house prices in these markets. In all four cities, the bottom tier of the market is showing the most rapid rate of price decline.

While prices have fallen almost everywhere since the peak of the bubble, it is striking how badly hit the bottom tier of housing has been in some of the most bubble-affected cities. Prices of bottom-tier homes are down by more than 50 percent from their bubble peaks in Chicago, Minneapolis and Los Angeles. They are down by more than 60 percent in Tampa and by more than 70 percent in Phoenix. Buying a moderate-income house in these markets near the peak of the bubble was an incredibly bad investment.

The biggest price increases in September were Cleveland with a 1.4 percent gain, followed by Washington with a 1.0 percent gain. The former was a reversal of price declines the prior two months, but prices in Washington have been consistently strong, rising at 7.0 percent annual rate over the last three months.

It seems likely that the current pattern of slowly declining house prices will persist into next year. There continues to be enormous excess supply in most areas, as evidenced most directly by the persistence of near-record vacancy rates. The continuation of extraordinarily low interest rates will be helpful, but on the other side the slow rate of job growth seems likely to persist through 2012.