•Press Release Globalization and Trade Latin America and the Caribbean World

January 7, 2020

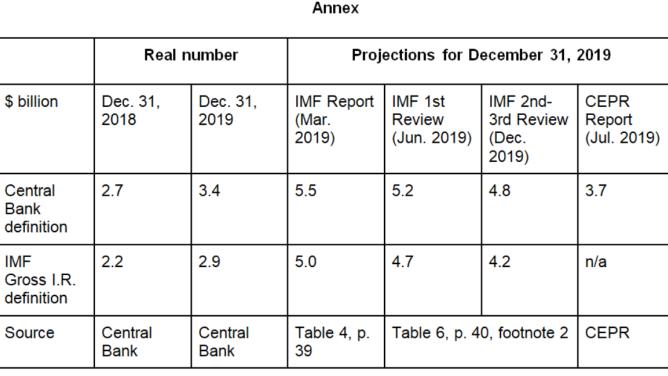

Ecuador’s $3.4b in Reserves Close to CEPR’s Prediction of $3.7b

For Immediate Release: January 7, 2020

Contact: Dan Beeton, 202-239-1460

Washington, DC ? Ecuador ended 2019 with just $3.4 billion in international reserves, compared to the over $5 billion that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had been predicting during most of 2019 that Ecuador would have, and which was the target level of reserves under Ecuador’s IMF program. By contrast, a July 2019 paper from the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) examining Ecuador’s IMF agreement stated: “we expect international reserves to reach $3.7 billion by year-end 2019.”

“It seems that the IMF’s lack of understanding about how Ecuador’s international reserves function, its wishful thinking with regards to capital flight and an over-confidence in its austerity program in Ecuador, led to some projections that ended up being way off,” CEPR Senior Research Fellow and paper coauthor Andrés Arauz said.

In its first report, in March 2019, the IMF predicted Ecuador would end 2019 with $5.5 billion (adjusted for the Central Bank’s calculation, see the table below) in “gross” international reserves. By the first review, in June 2019, the IMF had revised this downward to $5.2 billion. Even in December 2019, in a following review, the IMF predicted that Ecuador would have $4.8 billion in international reserves as it entered 2020. While CEPR erred by only 9 percent, the IMF’s predictions were off by a margin between 42 percent and 63 percent.

CEPR’s July 2019 paper noted: “… the IMF seems unclear on how international reserves work in a dollarized regime. With this faulty understanding, the IMF ambitiously shoots for $11.8 billion in (gross) international reserves by year-end 2022.”

By contrast, CEPR predicted that Ecuador’s international reserves would “decrease to $1.9 billion by year-end 2022.”

The IMF has a history of over-optimistic predictions for indicators for some countries under IMF agreements, and pessimistic projections in countries without such agreements and that have chosen a different policy course than that recommended by the IMF. As a 2007 CEPR paper noted, the IMF consistently made large errors in overestimating Argentina’s GDP growth for the years 2000, 2001, and 2002. This was during the country’s 1998–2002 depression, when the IMF was lending billions of dollars to support policies that ended in an economic collapse. For the years 2003–2006, after the Néstor Kirchner government in Argentina broke with the Fund, the IMF’s growth projections for Argentina fell far short of the actual numbers.

During and after the Global Recession, the IMF made overly optimistic economic growth projections in crisis-stricken Greece and Spain as these governments adhered to troika (European Commission, European Central Bank, and IMF) policy prescriptions.

“Ecuador is also likely to have lower per capita GDP, higher unemployment, and increased macroeconomic instability under the IMF program, which is all tragically unnecessary,” Arauz said. “Ecuador had no need for this ‘belt-tightening’; the IMF program is actively undoing a whole series of reforms and policies that contributed to generating economic growth, lowering unemployment, and reducing inequality and poverty. It is also disappointing, from a technical standpoint, that despite being off by 1.3–2.0 percentage points of GDP when measuring international reserves, the IMF has not corrected its projections of GDP growth.”

###