One of the most successful social movements of the twenty-first century occurred when thousands of parents and advocates won healthcare rights and insurance coverage for individuals with autism. Prior to 2001, neither commercial health insurance companies, nor Medicaid, covered services for people with autism. Most commercial health plans are governed by state laws, and winning insurance coverage required advocates to embark on a long state-by-state slog. But by 2015, thanks in large part to their push, all but seven states had mandates requiring commercial health plans to provide coverage for autism, with the remainder covered by 2019. In the meantime, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required its marketplace health plans to cover behavioral health, including autism services; and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) clarified in 2014 that all state Medicaid plans must cover the costs of regular screening, diagnosis, and treatment of autism.

This success is consequential because autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that begins at birth or early childhood. Many people who are diagnosed with ASD require supportive services over their life course. Autism now affects one in 36 children in the United States – a rate that has increased markedly over the last four decades.

The success of this social movement, however, has had unintended consequences. The flood of insurance and taxpayer money pouring into the ‘market for autism services’ has quickly flowed into the pockets of Wall Street financiers. Autism advocates won health insurance and Medicaid coverage for intensive autism services, especially Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), which is the most widely recognized evidence-based approach. The more intensive services, requiring more hours of therapy each week, allow for higher reimbursement opportunities compared to other approaches or to other developmental disorders. Private equity (PE) firms have taken advantage of this steady cash flow in a fragmented industry with many opportunities for consolidation – all in the context of no minimum provider service standards and little or no regulatory oversight.

As a result, since the mid-2010s, private equity firms have become dominant players in the market for autism services. They have bought out many provider organizations across the country and created massive national chains with the primary purpose of extracting high returns in a short period of time. Parents who fought for health insurance coverage for their kids expected the funds to be used to expand access to high quality services. They didn’t expect PE firms to move in and skim funds to pay high salaries to executives and outsized returns to private equity partners.

In fairness to the private equity industry, we note that some private equity firms have provided growth equity investments to owners of autism service organizations, which may help them expand their services. The demand for autism services has substantially outstripped supply over the last decade, due to better diagnoses and the increased availability of health insurance coverage. Small private equity firms with healthcare expertise may provide growth equity to meet the financial needs of autism service providers, as commercial bank loans are difficult for small businesses to access. Under these conditions, provider organizations may negotiate with private equity firms to make sure that the owners maintain complete control over staffing and care management practices. Here, private equity firms supply finance capital for productive uses, just as healthcare professionals and employees supply their skills and labor; and the autism services provider, with behavioral health expertise, controls strategy and management decisions.

The majority of PE activity in the autism sector, however, is in the buyout of existing providers, which does not necessarily lead to the expansion of services or opening of new sites. As detailed in this report, Blackstone’s buyout of the Center for Autism and Related Disorders (CARD) in 2018 led to the closure of over 100 sites only four years later and its bankruptcy by June, 2023. Moreover, as in the Blackstone case, when PE firms buy out providers, they often load them with excessive debt that they did not previously have. PE also takes over decision-making control of care management practices, despite having little or no expertise.

This report provides a comprehensive assessment of private equity activity in autism services. It examines the regulatory frameworks and reimbursement models for autism services in order to assess how and why private equity firms have entered this segment. It provides data on the extent and nature of buyouts since the 2000s, the private equity business model, and related outcomes. It draws on quantitative data as well as detailed cases of 12 leading private equity-owned national chains offering ABA services.

General Findings

Autism services became a ‘hot market’ for PE acquisitions only after widespread health insurance coverage became available by the mid-2010s. This occurred through passage of state health insurance mandates, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandate for coverage in its marketplace health plans, and the Medicaid mandate for coverage in 2014 of medically necessary services in behavioral health, including people with autism. Between 2017 and 2022, private equity firms completed 85 percent of all mergers and acquisitions in autism services – a rate not found in any other segment.

Detailed Case Study Findings

The 12-private-equity-owned ABA autism service chains examined in this study employ at least 30,000 people at 1,300 locations. Taken together, they cover the entire United States. Small providers were bought out and consolidated into massive chains by large generalist private equity buyout funds that had little or no behavioral health expertise. These PE firms are large multinational conglomerates investing in anything from fossil fuels to retail stores to autism clinics. As a result, they have diversified their risks so widely that if any of the autism service organizations they own falter, they can walk away, with few or no consequences – and they have.

The patterns of buyout activity in these cases have implications at three levels: at the industry level – in terms of consolidated market, political power, and extraction of third party and taxpayer funds; at the organizational level – in terms of the financial and organizational stability of providers; and at the clinical level – in terms of job quality, care quality, and equal access to services.

Equal access to care has also been affected, as some PE owners have prioritized patients who need more intensive hours per week in order to maximize billing revenues, while limiting or eliminating admission of those requiring fewer numbers of weekly service hours. Some PE-owned chains have prioritized patients with commercial insurance coverage over those with Medicaid. Some have shifted resources to states with higher reimbursement levels, while decreasing services in states with lower reimbursements. These policies increase inequality in access to treatment for patients.

The case presented here of Blackstone’s takeover and bankruptcy of CARD, the largest U.S. chain with some 250 clinics, illustrates in detail how private equity buyouts affect autism services at these three levels.

It is important to note that we do not argue that the patterns found in the leading case studies occur across the board. Rather, the evidence identifies the financial strategies and management practices of leading PE-owned corporations and associated outcomes.

Policy Implications

It is difficult to formulate policies to rein in greed and assure that funds are spent in keeping with the legislative intent of providing high quality care to individuals with autism. State-level regulation of commercial insurance companies is overseen by insurance commissioners in the 50 states and tends to be lax – with rare use of enforcement measures. Insurance companies are private payers that negotiate private contracts with providers.

But solutions exist. The autism community has developed strong professional and advocacy organizations that successfully passed state commercial health insurance coverage. They established professional standards for individual ABA practitioners through an independent Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB), and licensure requirements in most states. The Council of Autism Service Providers (CASP), a non-profit service provider association, has created practice guidelines that include minimum staff-client ratios and other care standards. The Autism Commission on Quality (ACQ) has created an accreditation process for providers, which may be used for state rule-making.

Now, these associations should push for state legislation to establish minimum care standards for provider organizations. These may include rules for minimum staff-client ratios and the mix of skills and qualifications needed to provide appropriate care. Legislation should include annual reporting requirements and monitoring and oversight that currently do not exist. The CMS has proposed that 80 percent of payments for Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and Medicaid managed care should go to direct care workers’ wages. Similar requirements may be developed for autism service providers.

We are grateful to the Omidyar Network for generous funding of this study. We are especially grateful to Dean Baker, Gina Green, Chris Jurgens, and Lorri Unumb for helpful comments on this paper, as well as the healthcare providers, workers, professionals, and industry specialists who gave their time and shared their knowledge and experiences with us.

One of the most successful social movements of the 21st century occurred when thousands of parents and advocates won healthcare rights and insurance coverage for individuals with autism. Prior to 2001, neither commercial health insurance companies nor Medicaid covered services for people with autism. Most commercial health plans are governed by state laws, and winning insurance coverage required a long state-by-state slog. But by 2015, all but seven states had passed meaningful health insurance for autism services, and the remainder were covered by 2019. In the meantime, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required its marketplace health plans to cover behavioral health, including autism treatment; and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) clarified in 2014 that all state Medicaid plans must cover the costs of regular screening, diagnosis, and treatment of autism.

This success is consequential because autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex developmental disorder that begins at birth or early childhood and can continue throughout the lifespan. Many people who are diagnosed with ASD require supportive services over the life course. The prevalence of ASD is increasing, due largely to greater awareness and broadened diagnostic criteria. It now affects one-in-36 children in the United States, up from 1-in-150 in 2000 (CDC 2023).

The unintended consequences of parents’ successful fight for their children’s healthcare, however, reflect deeper problems in the US healthcare system. The flood of money pouring into the ‘market for autism services’ has quickly flowed into the pockets of Wall Street financiers. Private equity, which had shown little interest in the autism ‘market’ before 2015, now found it to be ‘a hot market.’ Autism advocates had won health insurance and Medicaid coverage for intensive autism services, especially Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), the most widely recognized evidence-based approach. The more intensive services (higher numbers of hours per week) allow for higher billing opportunities compared to other approaches or services for other developmental disorders.

Market demand for autism services has grown steadily, with annual estimated revenues of $5-$7 billion. Spending for care is expected to continue to grow due to strong commercial health insurance and federal funding, earlier diagnoses of the condition, and a regulatory environment that is considered ‘favorable’ (KPMG 2023). The industry is fragmented, offering large opportunities for consolidation, and regulatory oversight in this market is thin or non-existent.

In this context, private equity firms quickly sought first-mover advantage. Between 2017 and 2022, PE firms completed 85 percent of all mergers and acquisitions in the autism healthcare segment, as detailed in this report — a rate not found in any other segment of healthcare or other industries. Private equity firms are now the dominant for-profit providers in the sector. They particularly targeted those provider organizations specializing in ABA because it is covered by state health insurance mandates and offers more opportunities for higher billing and revenue generation. They have created massive national chains with the primary purpose of extracting high returns in a short period of time.

Parents who fought for health insurance coverage for their autistic kids expected the funds to be used to expand access to high quality treatment. They didn’t expect PE firms to move in, skim reimbursements to pay high salaries to executives, and deliver millions to private equity partners. Blackstone’s takeover of the Center for Autism and Related Disorders (CARD), documented in this report, illustrates the dangers of this short-term model: Blackstone bought out the chain in 2018, loaded it with debt, and closed almost half of CARD’s 250 sites by 2022 – substantially decreasing, not increasing, access to care.

In fairness to the private equity industry, we note that some private equity firms have provided growth equity investments to owners of autism service organizations, which may have a positive effect. The demand for certain autism services has substantially outstripped supply over the last decade, due to better diagnoses and the availability of health insurance coverage. Small private equity firms with healthcare expertise may provide growth equity to meet the financial needs of autism service providers, as commercial bank loans are difficult for small businesses to access. Under these conditions, provider organizations may negotiate with private equity firms to make sure that the owners maintain complete control over staffing and care-management practices. Here, private equity firms supply finance capital for productive uses, just as healthcare professionals and employees supply their skills and labor; and the autism services provider, with behavioral health expertise, controls strategy and management decisions.

The majority of PE activity in the autism sector, however, is in the buyout and complete takeover of providers – as in the Blackstone case — sometimes loading them with substantial debt that they did not previously have. This private equity behavior is a cause for alarm because many people with autism require specialized and intensive services, including interventions such as ABA. When PE firms buy out provider organizations, they take control of care management practices despite having little or no expertise.

The contradictions of private equity ownership and control of autism service provider organizations are large. When PE firms create investment funds, they promise their investors ‘outsized’ financial returns – those that considerably beat the stock market and are much higher than other for-profit enterprises – all in a three to five-year period. Health insurance reimbursement rates for autism services, however, are pegged to the level of quality care needed – raising legitimate questions about how PE firms will maintain quality care while also delivering the financial returns they have promised.

In this report, we start with an overview of autism and its prevalence, followed by a discussion of autism health insurance mandates, payment models, and oversight regulations. We analyze trends in private equity buyouts, using the most complete and reliable data available. We then examine 12 leading private equity-owned ABA service chains, describing patterns of change pre-and post-buyout. We present evidence on outcomes of PE ownership at the industry, organizational, and site levels, based on these 12 leading cases. We also illustrate these patterns with a detailed analysis of the Center for Autism and Related Disorders (CARD). Our case studies draw on financial transaction data, company websites and announcements, investigative reports, academic studies, lawsuits, and interviews with a range of practitioners, autism and ABA services providers and therapists, and insurance experts. We close with a summary of findings and their policy implications.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent difficulties with communication and other social interactions and restricted, repetitive behaviors, interests, or activities. It is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, but as yet, no reliable biomarker has been identified and there is no medical diagnostic test; the condition is diagnosed behaviorally. Although ASD begins prenatally and may manifest itself within the first year of life, many individuals are not diagnosed until later in childhood or even in adolescence or adulthood. Many people with ASD require some level of supportive services throughout their life course (Autism Speaks 2023a; Goldstein 2018)

Understanding the complexity of ASD is important for understanding why private equity ownership and control of service providers in this segment is a poor fit. The “spectrum” in the disorder’s name refers to the fact that there are substantial variations in the ways the condition affects individuals. Current ASD diagnostic criteria identify impairments in three behavioral categories: reciprocal social interaction, communication, and restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. They also specify three levels of severity based on the amount of support necessitated by the individual’s impairments in these categories (Autism Speaks 2023a; Goldstein 2018; Martin, Pepa, and Lord 2018).

In addition to the core symptoms, ASD may be accompanied by intellectual or language impairments and other neurodevelopmental and behavioral disorders. For example, 31 percent of people with autism have an intelligence quotient (IQ) of less than 70, and 44 percent have an IQ of 85 or greater (Autism Speaks 2023a). Almost one-third are estimated to have very limited verbal communication skills; almost half are prone to wandering or bolting; and nearly one-third exhibit self-injurious behaviors. For these reasons, some refer to autism as ‘a whole-body disorder’ (Croen et al. 2015).

The prevalence of ASD is increasing, apparently due to greater awareness, broadened diagnostic criteria, and research in brain development, genetics, and related areas. In the year 2000, one in 150 children aged 8 were identified with autism, compared to one in 88 in 2008, one in 44 in 2018, and one in 36 in 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control (2022, 2023). A separate CDC study in 2020 estimated that over 5.4 million adults are on the autism spectrum, or 2.2 percent of the US population (Dietz et al. 2020). Boys are four times more likely than girls to receive the diagnosis (Autism Speaks 2023a; CDC 2023).

Treatment Alternatives

Research into the treatment of autism began in the 1960s, with a series of intervention studies focused on behavioral approaches that emphasize positive reinforcement of behaviors to promote a child’s development. Starting in the 1970s, UCLA psychologist Ivar Lovaas published research on intensive, comprehensive behavioral intervention for preschool-aged children with autism, which became known as Applied Behavior Analysis. His 1987 study showed that nine of 19 children who received such intervention for up to 40 hours per week for at least two years had substantial improvements in intellectual and language skills and completed first grade successfully without specialized services (Lovaas 1987). Since then, a substantial body of research has documented the effectiveness of intensive, comprehensive ABA intervention (30+ hours per week) for young children with ASD. ABA therapy is based on the development of individualized treatment plans that break down skills into small concrete tasks that clients learn through repetition and positive reinforcement (Autism Speaks n.d.).

Many other scientific studies have shown that a wide range of ABA procedures are effective, singly or in various combinations, for building useful skills and reducing challenging behaviors in people with ASD throughout the lifespan. Thus, comprehensive ABA treatment (addressing many skills and challenging behaviors) as well as focused ABA treatments (targeting a small number of skills or behaviors) are deemed scientifically supported and medically necessary for many individuals with ASD (Association of Professional Behavior Analysts 2017; ASAT n.d.; ABA Coding Coalition 2022; Autism Speaks 2023a). Based on this scientific evidence, ABA approaches have become widely accepted, and as detailed below, are covered by state commercial health insurance mandates.

Criticisms of the ABA approach, however, have grown over time. Some are based on the limitations in existing research or the lack of skilled practitioners. Others grow out of the neurodiversity movement, which holds that neurological variation and functioning are a natural and valuable part of human variation. Others view neurodiversity as a social justice issue linked to the wider disability rights movement (Leadbitter, Buckle, Ellis, and Dekker 2021). The Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN) argues that “…autistic people need to be involved whenever autism is discussed” (ASAN 2023).

A wide range of alternative therapies do exist, including occupational, speech, educational, relationship-based (Floortime), pharmacological, and others; and these may serve the diverse needs of different people. Some of these approaches, including occupational and speech therapies, are well-established disciplines long covered by health insurance. A central problem, however, is that many alternative approaches are not yet covered by state commercial health insurance mandates due to lack of sufficient scientific evidence regarding their effectiveness (ASAT n.d.). For this reason, private equity firms have targeted ABA therapy providers over others.

Private equity buyouts in autism services took off in the mid-2010s, only after most states had mandated commercial health insurance coverage for intensive autism services, with specific reference to ABA. States varied in their specific rules, but generally required payers to cover all medically necessary services, including screening, diagnosis, and appropriate individualized treatments (e.g. behavioral, pharmaceutical, psychological, therapeutic).

Through most of the 2000s, neither government nor commercial health insurance covered autism services in most states. Those commercial health plans with mental health coverage contained language that was sufficiently ambiguous that courts rejected parents’ lawsuits to win coverage (Unumb and Unumb 2011). Southern states were the first to adopt autism insurance mandates – South Carolina and Texas in 2007, and six other states in 2008. The South Carolina law, co-authored by lawyers Lorri and Dan Unumb, was named ‘Ryan’s Law’ after their son (Unumb and Unumb 2011). The national advocacy group Autism Speaks then hired Lorri Unumb to lead a movement for state-by-state passage of laws based on the South Carolina template, which specified clear definitions of autism and coverage of all medically necessary services, including ABA services. By 2010, 23 states had passed some version of Ryan’s law; by 2013, 34 states; by 2015, 43 states, and by 2019, 50 states plus DC (See Figure I).

Figure I: State Level Autism Health insurance Reform: 2001-2019

Source: Autism Speaks. 2023b.

The 2010 ACA also helped expand widescale coverage of behavioral health services, but did not set a national standard per se. It required all health insurance plans to cover preventative services without cost-sharing, including autism screening for young children. It disallowed maximum lifetime dollar limits and allowed children to be covered on their parents’ plans till age 26. As of 2014, the ACA prohibited the denial of coverage due to pre-existing conditions such as autism and required the new individual Marketplace Insurance Plans to cover behavioral health, including autism.

Medicaid coverage of autism was not clarified until 2014. In what became known as the ‘July 7th memo’, CMS clarified that Medicaid must cover all medically necessary services for autism, including Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) services for children and adolescents up to age 21 (CMS 2014). By 2022, all states had clarified that EPSDT was a covered benefit. After 2014, 45 percent of employer-provided self-funded plans with over 500 employees included coverage for intensive autism or ABA services (Autism Speaks 2022a).

As a result of these developments, the largest proportion of funding for healthcare services for people with ASD comes from commercial health insurance plans. Here, supplemental Medicaid is available, but not universally, and its level of generosity varies across states. For those who do not have commercial health insurance, state Medicaid programs are supposed to cover ABA services for all eligible individuals ages 0 – 21, regardless of income level, based on Obama era federal mandates; and Medicaid reimbursement rates were pegged to state-level commercial reimbursement rates. Other sources of funding for healthcare services are available for different beneficiaries, as indicated in Table I.

|

Table I: Health Insurance Plans Covering Autism Services, 2023 |

|

|

State autism insurance laws requiring coverage of ASD services by commercial and state employee benefit plans |

Individual state mandates passed: |

|

Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit |

Children who qualify for Medicaid are entitled to all ‘medically necessary’ services under EPSDT, as determined by the state. In 2014, CMS clarified that ABA is a covered benefit. As of February 2022, all states cover ABA services, although system barriers exist in eight states. |

|

Marketplace health insurance (under the ACA) |

As of 2014, all Marketplace Plans were required to cover 10 essential health benefits, including services for people with ASD; 33 states include ABA services as a mandated benefit under these plans |

|

Federal Employee Health Benefit (FEHB) |

FEHB plans cover 8.2 million federal employees, retirees, and dependents, and as of January 2017, were required to cover ABA services for people diagnosed with ASD |

|

TRICARE health benefit program for service members, families |

TRICARE covers ABA services for military beneficiaries with autism under the Autism Care Demonstration Program |

|

Self-funded employer plans, regulated by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) |

Employer plans are not subject to state laws, but are regulated by federal ERISA rules, with employer discretion over benefit design w/in federal guidelines. By 2018, 45% of companies with 500+ employees had coverage for ABA or other behavioral services – a percentage that is now much higher. |

|

Source: Autism Speaks (2022b). |

|

Currently, each state’s insurance regulator sets rules and reimbursement rates for ABA services for the commercial health plans that do business in their jurisdiction. Those rules, along with restrictions in some of the autism insurance laws (e.g., caps on the age of eligible beneficiaries with ASD, number of visits, dollar amounts), have led to considerable variation in funding levels, scope of covered services, and who is covered. This variation has provided incentives for private equity firms to target some age groups more than others and some states more than others.

Reimbursement rates for ABA services are generally based on a set of 10 CPT® codes issued by the American Medical Association (ABA Coding Coalition 2023). ABA providers are reimbursed for services based on the number of hours or 15-minute units of services delivered to a patient and their caregivers and the type of coverage in the patient’s health plan as shown in Table 1 (Unumb and Unumb 2011; Autism Speaks 2023).

Because private equity is a relatively new phenomenon in the autism healthcare services segment, it is important to clarify what the private equity business model is and how it differs from non-profit and for-profit enterprises. For-profit and private equity-owned companies are often conflated, or lumped together as investor-owned enterprises, as in a recent article entitled, “Private Equity Investment: Friend or Foe to Applied Behavior Analysis?” (Litvak 2023). The article often interchanges the terms for-profit, investor-owned, or organizations with investment capital or external capital. Much of the evidence regarding for-profit or investor-owned entities comes from the 2000s, when private equity was not active in behavioral health. The article does not address private equity ownership, despite its title.

‘Investor owned’ companies may be for-profit or private equity-owned, and the differences are profound. For-profit enterprises may be owned entirely by the founder (for example, a parent or an ABA therapist) or by many different investors (as in publicly-traded corporations). The investors put their own money at risk (equity), expect reasonable returns (for example, in line with the stock market); and the enterprise increases profits and returns to investors by effectively managing productive (healthcare) activities. For-profit providers are typically focused on building sustainable healthcare services, with a long-term commitment to growth and development. They are also held legally accountable for any financial or patient care errors or wrong-doing in their organizations, and if publicly-traded, must submit detailed financial reports to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). They may attract private equity capital as financial backing, in which case private equity is just like any other shareholder — earning a return by supplying finance capital for productive uses, just as healthcare professionals and employees supply their skills and labor. In those instances, the provider/owner, with behavioral health expertise, maintains control over staffing and care-management protocols.

The private equity buyout model is radically different. First, the private equity general partners (GPs), who are in charge of raising an investment fund, put very little of their own money at risk – typically one to two percent of the equity in the investment fund. Because they primarily use other people’s money, they are far less risk averse than for-profit (or non-profit) enterprises. The GPs use the buyout fund to acquire enterprises (called portfolio companies), and take complete control over them. The PE firm may have multiple funds going at once, and own multiple companies within each fund, thereby spreading risk over many legally-separate entities. Thus, if any one enterprise performs poorly, the PE firm can walk away largely unscathed. The fund investors may suffer greater losses, but they have committed their money for 10 years, so they cannot exit the PE fund.

When private equity buys out a company, it simply acquires existing companies (e.g. ASD providers), and does not necessarily invest in new services. The PE general partner typically takes charge of top management decisions, which in autism services may include care management practices. In behavioral health, there are few guardrails against financial actors making healthcare decisions. For example, behavioral health is not governed by Corporate Practice of Medicine laws, which prohibit corporations from practicing medicine or employing a physician to provide professional medical service. Moreover, if the enterprise ends up in financial distress or is found guilty of billing fraud or patient abuse, the private equity fund and its general partner (considered ‘passive investors’) are not held accountable – the portfolio company is. And any wrongdoing is attributed to the portfolio company (the autism services company in this case), damaging its reputation, despite the fact that the PE general partner has made the decisions: Essentially, the ‘puppeteer’ pulling the strings is not held accountable. Moreover, private equity firms have only minimal SEC reporting requirements, and none for the portfolio companies they take private – hence, little to no transparency or accountability.

The private equity business model also relies on considerable debt to buy out enterprises (referred to as a leveraged buyout or LBO), based on the size of the organization. In health care, the debt used in an initial buyout of a small provider may be modest, but the PE firm uses an initial buyout to create a platform, and then buys out and adds on other enterprises to create a large chain. As the enterprise grows through mergers and acquisitions (M&As), private equity can increase the amount of debt used in each buyout as the platform grows in size. This means that post-buyout, enterprises that had no prior debt may now be saddled with substantial debt, with interest payments digging into net revenues.

PE-owned enterprises also differ in their approach to profit-making and investor returns. Private equity firms promise their investors ‘outsized returns’ that substantially beat the stock market – sometimes referred to as the ‘shareholder model on steroids’ – and they do so not only through operational strategies, but also various financial tactics, such as the use of debt or selling assets. Private equity firms typically deliver returns in a short five-year window, exiting their buyout by then and distributing returns, regardless of the impact on the healthcare enterprise. In sum, the private equity business model, which promises short-term outsized returns, intensifies incentives for cost-cutting and revenue enhancement that go far beyond the incentives found in the for-profit, let alone the non-profit, model.

In this section, we discuss the trends of private equity buyouts and how they responded to changes in federal and state laws governing health insurance coverage of services for people with ASD, drawing on the most reliable data available. We then turn to patterns of PE financial strategies, management practices, and outcomes, based on available evidence from 12 leading cases of PE buyouts of ABA providers. While the cases are not representative of the population of PE buyouts, they show patterns of behavior across the leading PE-owned large chains – those whose practices affect thousands of workers and families. The cases also provide insights into how the structure of regulatory oversight and payment models allow financial actors to take advantage of program funding, if they choose to do so.

Building a database of evidence on private equity strategies is challenging because private equity is private – offering little or no transparency. To overcome this, we triangulated information from many publicly available sources as well as interviews. Our evidence is based on data from leading industry research consulting firms (The Braff Group, Mertz-Taggert, PitchBook); company websites and press announcements; whistleblower and False Claims Act lawsuits; investigative reports by major media outlets, as well as healthcare specific outlets (Modern Healthcare, Becker Review, STAT, Behavioral Health News), and other online sources; and interviews with academic experts, industry consultants, ABA specialists, service providers, and former managers and employees of PE-owned companies. We build on the important academic research by Laura Olson (2022) and recent investigative reports by Eileen O’Grady (2020, 2022), Tara Bannow (2022), Erika Fry (2022), and others, as cited below. It is noteworthy that local journalists, public radio reporters, and advocacy groups have played a key role in uncovering evidence of poor management or care practices – with government investigators following up on their leads. This pattern is suggestive of the lack of regulatory oversight by government agencies.

Private Equity Buyout Trends

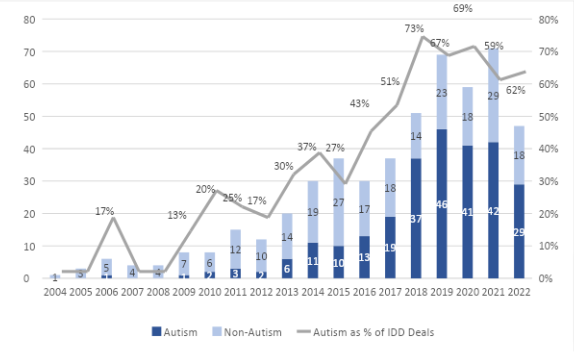

We begin our analysis of buyout trends by comparing the merger and acquisition activity of all players in autism services compared to their activity in the broader segment of intellectual and developmental disorders (IDD). As shown in Figure I, little or no M&A activity existed in the 2000s; and where it did, it was largely in the IDD services segment. Buyouts in IDD services have gone up and down over the last decade, averaging about 19 per year. There is no real upward trend.

By contrast, buyouts in autism services represented a small percentage of all IDD buyouts until about 2016, when they accelerated quickly, and represented about two-thirds of all deals from then on. This pattern is explained by the timing of the state autism insurance and Medicaid mandates, which kicked in from the mid-2010s on, and provided higher relative reimbursement payments based on the intensity of services provided. IDD services, by contrast, are primarily covered by Medicaid, and reimbursements are considerably lower than for ABA autism services.

ABA autism services companies are also more attractive because they are more scalable – both in terms of the number of clients per site and the gains from buying out provider organizations and building national chains with brand recognition. In IDD services more generally, pressure has been to deinstitutionalize services to ever smaller community-based homes, especially for adults.

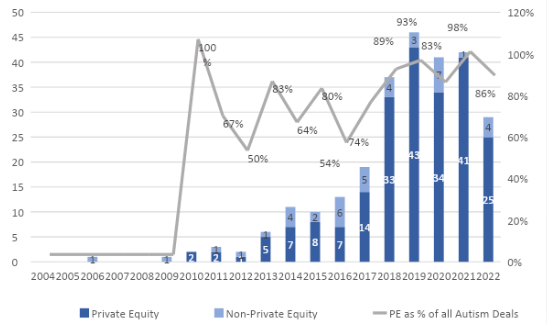

While Figure I shows that buyouts of autism service providers have dominated the IDD services segment overall, Figure II indicates that private equity firms have been driving those buyouts. PE firms engaged in a handful of buyouts in 2013-2016, but were responsible for 85 percent of the deals in that market from 2017-2022. By this time, virtually all major health insurance companies covered ABA services, including Aetna, BlueCross BlueShield, Optum, Beacon Health Options, Cigna, United Healthcare as well as ACA Marketplace plans, government employee plans, and Medicaid in the states that have adopted Medicaid expansion under the ACA (Table I). ABA services became the dominant form of behavioral health insurance nationally, with over 200 million people with ASD covered by 2019.

Figure II: Autism Services M&As as Percent of all IDD Services, 2004-2022 (Q3)

Source: The Braff Group

The market for buying autism service providers also heated up because PE firms were sitting on an excessive accumulation of funds committed by their limited partners (referred to as dry powder). They were under pressure to buy out companies and begin distributing returns to their investors. The competition among PE firms to buy up providers led to an escalation of prices for target companies – and the hot market was based in large part on speculation – that PE firms could buy low and sell high, similar to real estate speculation. In healthcare services as a whole, the average leveraged buyout purchase price in 2017 was 8X EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization). But by 2018 and thereafter, the average rose to 12X and 13X EBITDA (PitchBook 2022). And in the ‘hotter’ autism market, prices reached upwards of 14X EBITDA. PE firms that pay so much for an acquisition are under great pressure to figure out how to extract wealth from their ABA provider organizations in order to deliver the returns they have promised their investors.

Figure III: Private Equity as % of All Autism Services Deals, 2004-2022 (Q3)

Source: The Braff Group

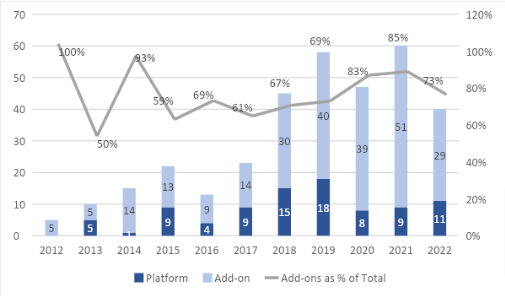

Another pattern is the rapid growth through leveraged buyout ‘add-ons’ that PE firms have undertaken immediately after they buy out or establish an initial company. They buy up and add on more ABA providers to increase size and grab market share. This strategy also allows them to avoid federal antitrust scrutiny because each acquisition is small enough that it is below the threshold needed to trigger such scrutiny (known as the ‘Scott-Hart-Rodino threshold’). Figure III is based on all available deal data in this segment, provided by The Braff Group, and shows that growth has occurred primarily through the use of add-on deals, especially in the 2017-2022 period.

Note that these numbers underestimate PE’s actual penetration in this market because each deal represents one provider, but that provider could encompass multiple locations. PE firm Kohlberg, Kravitz, and Roberts (KKR) entered the ABA market in 2017 by creating a platform called BlueSprig Pediatrics. PitchBook lists KKR’s BlueSprig as completing eight add-ons in three years, but the number of locations grew from one to 160 across 15 states. Blackstone’s buyout of the Center for Autism and Related Disorders (CARD) is coded as one deal in the databases, but it included about 250 locations in many states. No reliable capital investment data exists because most PE firms have stopped reporting those numbers; and as they rely increasingly on other PE firms for loans, the amount of debt used in these transactions is unavailable. This lack of public reporting of private equity financial transactions means that policymakers and the public rarely know whether these deals may lead to financial instability of autism service providers.

Figure IV: PE Deals in ABA Autism Providers: Platforms and Add-ons, 2012-2022 (Q3)

Source: The Braff Group

Private Equity’s Impact in Autism Services

Private equity firms are now the dominant owners of for-profit ABA chains in the autism services segment, with roughly 135 private equity firms currently active, according to data from PitchBook. Through the analysis of 12 of the largest PE-owned ABA autism services chains, we identify patterns of change associated with private equity ownership. Note that we do not argue that the patterns identified below occur across the industry.

Table II provides a list of the private equity firms that have played the dominant roles in buying out (at some point) the 12 companies in this study (note this does not include PE firms that have provided small amounts of minority financing). All but three of the 17 PE firms involved in these buyouts are large generalist firms, with ‘large’ generally defined as those with several billion or more in assets under management (AUM). Together they control $1.8 trillion in AUM and currently own a total of 1,526 companies strewn across many different industries – from finance to energy to a variety of business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) services. The total number of companies they have ever owned is 3,763. The only thing that the companies have in common is that they are owned by PE firms with financial expertise.

Table II: Characteristics of Private Equity Owners of 12 Case Study Companies

|

ASD Provider |

PE firms |

Size, Type |

% Assets Healthcare |

All Industries |

AUM ($ B)* |

# Active Cos.* |

# All Cos.* |

|

Action Behavior Center |

NexPhase Capital |

Large, Buyout |

40% |

HC, B2B, B2C, IT, Fin, Materials |

1.8 |

15 |

83 |

|

Charlebank Capital |

Large, Buyout |

9% |

Fin, IT, B2B, B2C, HC, Materials, Energy |

13.1 |

42 |

483 |

|

|

Autism Learning Ptners |

FFL Partners |

Large, Buyout |

43% |

HC, B2B, Fin, B2C, IT |

5.0 |

18 |

153 |

|

Blue Sprig Pediatrics |

KKR |

Large, Buyout |

10% |

B2B, B2C, IT, Fin, HC, Energy, Materials |

504.0 |

431 |

2278 |

|

Caravel Autism Health |

Frazier Healthcare Partners |

Mid-Lge, Buyout |

90% |

HC, B2B, IT, Materials, B2C |

4.1 |

42 |

439 |

|

CARD |

Blackstone |

Large, Buyout |

6% |

B2B, IT, B2C, Fin, HC, Energy, Materials |

991.0 |

448 |

1946 |

|

Centria Healthcare |

Martis Capital |

Midsize, Buyout |

82% |

HC, B2B, B2C, IT, Fin, Materials |

2.0 |

18 |

61 |

|

Thomas Lee Partners |

Large, Buyout |

17% |

B2B, B2C, IT, HC, Fin, Materials, Energy |

17.7 |

34 |

500 |

|

|

Hopebridge Autism Therapy |

Arsenal Capital |

Large, Buyout |

24% |

B2B, Materials, HC, IT, Fin, B2C |

11.1 |

20 |

270 |

|

Invo Healthcare Associates |

Golden Gate Capital |

Large, Buyout |

5% |

IT, B2B, B2C, Fin, HC, Materials, Energy |

12.2 |

26 |

349 |

|

Ares Capital |

Large, Buyout |

13% |

B2C, B2B, HC, Energy, Fin, Materials, IT |

33.4 |

20 |

141 |

|

|

Kadiant |

TPG Capital |

Large, Buyout |

22% |

IT, HC, B2B, B2C, Fin, Energy, Materials |

135.0 |

262 |

1720 |

|

LEARN Behavioral |

LLR Partners |

Large, Buyout |

31% |

IT, HC, B2B, B2C, Fin, Materials |

4.6 |

48 |

388 |

|

Gryphon Investors |

Large, Buyout |

25% |

B2B, HC, B2C, IT, Materials, Fin, Energy |

8.9 |

33 |

318 |

|

|

SC Early Autism |

Chance-Light (Graham HC Cap) |

Small, Buyout |

100% |

HC |

0.8 |

8 |

NA |

|

Stepping Stones Grp |

Five Arrows Capital |

Large, Buyout |

39% |

HC, IT, B2B, B2C |

18.0 |

7 |

37 |

|

Leonard Green & Partners |

Large, Buyout |

13% |

B2B, B2C, HC, IT, Fin, Materials, Energy |

70.0 |

54 |

594 |

|

|

Totals |

|

|

|

|

1,833 |

1,526 |

9,760 |

Source: PitchBook Data. B2B = business-to-business; B2C = business-to-consumer;

HC = healthcare.

Some of the PE firms have allocated a sizable portion of their assets to health care, but recall that health care includes everything from IT to medical equipment manufacturing to pharmaceuticals, hospitals, or physician practices, and some do hire industry experts to provide consulting advice. But it is improbable that they have expertise in all of these different segments, and only a tiny proportion of assets are allocated to behavioral health, and an even smaller percentage to autism services.

This type of corporate entity is referred to as a diversified conglomerate. Each company in the PE firm’s portfolio is legally separate, with risk diversified across a large number of companies so that if anything goes wrong in one, the PE firm is not affected. The PE firm is maximizing profits at the level of the PE firm, not at the level of each portfolio company, which is used to maximize cash flow up to the PE firm. For example, Blackstone has risk diversified across 448 companies currently, KKR, 431 companies, TPG Capital, 262 companies.

We realize that small boutique firms that specialize in health care may be quite different from large generalist firms, which constitute the majority of our cases. We have argued that it may be likely that smaller PE firms that specialize in health care may be more knowledgeable and able to conform to healthcare legal requirements and provide better care. But as our case evidence below shows, South Carolina Early Autism, which had a serious and on-going record of Medicaid fraud, was bought out by a small private equity firm with 100% of its AUM in healthcare. Centria, the leading ASD provider in Michigan, owned by a midsized PE firm, Martis Capital (with 82 percent of assets in healthcare), was found to have over 100 substantiated allegations of abuse, neglect, and use of unwarranted force on children, as detailed below. Thus, size and specialization in healthcare do not always mean that the PE firm is more likely to adopt appropriate standards of care and conform to Medicaid rules.

Based on the case study evidence below, we illustrate how these private equity firms have affected autism services at three levels: At the industry, organizational, and clinical care levels.

Industry Level Effects

The private equity-owned corporate chains examined here are listed in Table III (data summarized from Appendix A). At the industry level, they are having a profound effect as the primary movers in the rapid consolidation of small providers into large corporate chains. The 12 case study corporations alone employ roughly 30,000 employees at 1,265 locations, with an average corporate footprint of 15 states each. This gives the large chains competitive advantage over other non-profit and for-profit enterprises. While some have initially entered the market through growth equity investments (perhaps as part of due diligence), most have used classic leveraged buyouts.

Table III: Private Equity Buyout Case Studies*

|

ABA Provider |

PE Deal Type, Date, Firm |

Size (2023) |

# Flips/ # Years |

|

|

Action Behavior Center |

• 2018: NexPhase Cap., Juna Equity Ptnrs; (growth) |

• States: 5 |

1/4 |

|

|

Autism Learning Partners |

• 2009: Great Point Ptnrs., Jeff. River Cap. (growth) |

• States: 17 |

2/7 |

|

|

Blue Sprig Pediatrics, Inc. |

• 2017: KKR |

• States: 15 |

1/5 |

|

|

Caravel Autism Health |

• 2014: Search Fund Ptnrs., Graue Mill Prtns., Wolf Point Growth Prtns., The Cambria Grp., The Operand Grp. and Endurance Search Ptnrs. (LBO) |

• States: 7 |

1/4 |

|

|

CARD |

• 2018: Blackstone (LBO) • 2023: Pantogran LLC |

• States: 5 |

1/5 |

|

|

Centria Healthcare |

• 2016: Capricorn Healthcare (rebranded Martis Capital) |

• States: 13 |

1/3 |

|

|

Hopebridge Autism Therapy |

• 2014-16: VC funding (Seed) |

• States: 12 |

1/2 |

|

|

Invo Healthcare Associates |

• 2013: Post Capital Ptnrs. (LBO) |

• States: 30+ |

2/6 |

|

|

Kadiant |

• 2019: TPG Cap. (PE), Vide Ventures (VC), Kadiant CEO Lani Fritts • 2019-2022: 9 LBO add-ons |

• States: 8 |

1/4 |

|

|

LEARN Behavioral (was Learn It Systems) |

• 2010: Milestone Ptrns. (growth equity) |

• States: 18 |

2/9 |

|

|

S. Carolina Early Autism Project HQ: Sumter, SC Founded: 1998 |

• 2013: ChanceLight (LBO) • 2023: Graham Healthcare Cap. (SBO); add-on to Surpass BH |

• States: 6 • Sites: 29 |

1/10 |

|

|

Stepping Stones Group |

• 2014: Shore Cap. Ptnrs. BPEA, Resolute Cap. |

• States: 45 |

2/8 |

|

|

See Appendix A; Growth = growth equity; LBO = leveraged buyout; SBO = 2ndary buyout (one PE firm-to-another). |

||||

Table IV below summarizes the influence of the leading PE-owned companies at the industry, organizational, and site levels. It is based on the fuller details provided in Appendix A.

The leading companies in this study are also owned by large generalist buyout firms – that is, PE firms that have raised multiple investment funds and have diversified risk across several funds and across multiple companies within funds. If one provider does poorly, they can shut it down, as in the case of Blackstone’s ownership of CARD, discussed below. They act as large conglomerates targeting buyouts as purely financial transactions. Their financial strategies are then copied by other autism service providers.

Table IV: Private Equity Buyout Case Study Outcomes (Summary)

|

PE-owned providers |

Industry: |

Organizations: |

Sites: |

||||||||

|

Name of Provider |

Excessive Consolidation |

Sales: PE-PE firms |

Large generalist PE firms |

Excessive debt* |

Quick flips (~4 yrs) |

New CEOs, no BH expertise* |

Excessive Mgr/ EE turnover* |

Poor staffing, training, supervision* |

Cuts: wages, benefits, jobs* |

Unethical behavior; unequal access; poor care, abuse* |

Improper billing, fraud* |

|

Action Behavior Center |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

|

Autism Learning Partners |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Blue Sprig Pediatrics, Inc. |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||

|

Caravel Autism Health |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||

|

CARD |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Centria Healthcare |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Hopebridge Autism Therapy |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Invo Healthcare Associates |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Kadiant |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

LEARN Behavioral |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

S. C. Early Autism |

X |

X |

|||||||||

|

Stepping Stones Group |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

Note: Summary of findings from Appendix A. See full list of sources there and in text. * = Blank cell for these columns means that no data is available on whether the practice existed.

The dominance of large PE-owned corporations also allows them to have political power vis-à-vis government actors. Our case evidence below suggests that some have used this leverage to extract higher reimbursements for themselves under threat of closing down programs in states in which they do not get the reimbursement levels they prefer. CARD under Blackstone’s ownership was a leading example.

Organizational Effects

Private equity buyouts have had several effects on ABA provider organizations. One positive note is that some PE firms have provided growth equity to providers, filling a large hole caused by consolidation of local and regional banks into national chains that find it too expensive to serve smaller companies. This funding allows providers to grow, while still controlling management decisions. This kind of growth equity has given PE firms a positive reputation in the ABA community because they are one of the few sources of financing available to expand services, as noted in our and other researchers’ interviews with owner-entrepreneurs (Olson 2022). But initial growth equity investments in the cases here quickly turned into full-fledged buyouts. Moreover, in most of our case study examples, PE firms entered the market via large buyouts, not growth equity investments – such as those by KKR (Blue Sprig, 2017), Blackstone (CARD, 2018), and Thomas Lee Partners (Centria, 2019),

There are four primary ways that private equity buyouts have negatively affected financial and organizational stability in our case study companies. First, PE firms typically expand the size of their portfolio companies by using considerable debt in LBO add-ons, which is loaded on the portfolio platforms. This allows PE firms to extract higher returns upon exit while the company retains the debt. Public information on debt levels is largely unavailable now as PE firms have increasingly accessed loans from debt funds of other PE firms, thereby avoiding public disclosure of leverage levels. Nonetheless, we gathered publicly available and interview evidence showing that at least eight of the 12 companies in this study had substantial increases in debt post-buyout – in companies that previously had little or no debt. Olson reports, for example, that the former owner of Autism Learning Partners was stunned by the level of debt the PE firm had loaded on his company post-buyout, questioning “whether the company would survive” (Olson 2022: 232).

Second, as noted above, the PE firms in this study used their ABA provider acquisitions for ‘horse-trading’ among themselves. In all of our cases, PE growth equity investments or leveraged buyouts were followed by secondary buyouts (selling to another PE fund, or SBOs), and, in some cases, yet another. On average, the case study PE firms sold out to another PE firm every four years. This is even shorter than the overall patterns of hold times for all PE buyouts of IDD services (averaging 4.75 years), according to PitchBook data. These quick flips increase the likelihood of providers’ financial instability, as a series of PE firms buy, extract wealth, and resell autism service organizations to other PE firms – typically at higher multiples – all designed to meet promises of outsized investor returns.

Given that successful target companies are in high demand in the ABA autism services market, why don’t PE owners hold on to their portfolio companies and build long-term systems of care? And if some PE owners are exiting, why are others entering the market at the same pace? The answer is that these short-term financial plays are timed to meet the needs of PE firms: Those exiting need to distribute returns to their limited partner investors, while those entering have capital commitments from their investors that they are under pressure to invest somewhere. A good example from Appendix A is Action Behavior Centers, where the primary PE firm, NexPhase Capital, increased the size of the provider by 32-fold – from 5 locations to 162 in four years – and flipped the property in an SBO to Charlesbank Capital Partners. Neither firm had any prior experience with autism services provision.

This level of ownership churn creates organizational chaos, with rapid-fire changes in top leadership and in operational and care management policies. Most PE firms insist on installing their own top leadership team shortly after they take control of provider organizations, as documented by Olson (2022) and former provider/owners we interviewed. These former owners report that they stayed for a short transition period, that the new PE owners largely ignored their advice with respect to care management practices, and that they were replaced by top managers with financial, rather than prior behavioral health, experience or training. And when top leaders leave, their best managers often follow, as shown in academic research. High rates of management turnover also drive high rates of turnover among subordinates, especially when the managers are experienced leaders in their organizations and their replacements have little or no relevant experience. Quit rates also spike when involuntary dismissals increase (Li, Hausknecht, and Dragoni 2020). These are exactly the conditions created by private equity leveraged buyouts and the quick pace of secondary buyouts found in this study.

In sum, large PE generalist firms have entered the autism services market, adopted accelerated growth strategies to increase the size and value of portfolio companies, allowing them to exit quickly at a high price via secondary buyouts to other PE firms. There is suggestive evidence that these buyouts substantially increase the debt load of ABA autism service providers, replace experienced healthcare leaders with financial experts, create operational disruption, and result in higher levels of management and employee turnover.

Site-Level Outcomes

The organizational churn described above has particularly negative effects for people with autism. Their progress in overcoming challenging conditions associated with autism depends importantly on stable relationships of trust with caregivers. When they have to start over and over again with a new therapist or technician, their progress is undermined. Thus, private equity horse-trading of ABA provider agencies creates frequent disruption in management practices, the loss of skilled employees, and in turn, erodes the quality of care.

Private equity firms in ABA services have driven other changes in corporate policies that affect staffing and care management practices at the unit or site level via cost cutting, questionable care management practices, or improper or fraudulent billing practices.

To understand how this occurs and why these practices have negative effects, it is necessary to understand the level of individualized care and high staffing levels required for ABA services. Each ABA field site hires certified professionals — Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs) – to develop and oversee individualized treatment plans for patients. The behavior analyst conducts a detailed assessment and develops a treatment plan for the individual, based on information about their strengths, challenges, and preferences from the diagnostic evaluation, and interviews with the individual (if feasible) and their family. The behavior analysts train technicians to implement the treatment plans, oversee implementation, review data on patient progress frequently, and revise protocols and treatment plans as needed. They also train the patient’s parents and other caregivers to implement certain components of the treatment plan with the patient to the extent feasible (ABA Coding Coalition 2022; BACB 2023a).

The intensity of treatment (typically defined as the number of hours per week) should be based on the best available scientific evidence and what is medically necessary for the patient, i.e., what is needed to ameliorate their symptoms and improve overall functioning. Comprehensive treatment necessarily involves large numbers of treatment hours per week for an extended period of time. Focused ABA treatments tend to be less intensive in general, but large numbers of hours of treatment may be needed to address skills that are severely deficient or behaviors that put the patient or others at risk.

Health plans are billed for the hours (or 15-minute units) of ABA services that are delivered to the patient and caregivers. According to practitioners in the field, attempts to game the system do not occur through ‘upcoding’ as is known to occur in other services. Rather, autism service providers can take different approaches. They can maintain reimbursement rates and reduce costs by decreasing the ratio of professional behavior analysts to patients from the recommended 1:10-15 (ABA Coding Coalition 2022), to say, 1: 25-40; or similarly reduce the ratio of behavior technicians to patients.

They also can standardize treatment plans and require BCBAs to take on more children, even though all plans are supposed to be individualized. They can increase revenues by selecting children for admission with lower acuity conditions by telling the parents that their children need more hours of services than they actually may need. As one experienced leader in the autism community noted, “It’s easier to have 10 kids and bill for 40 hours per week each than to bill 40 kids at 10 hours per week…. They are convincing parents early on that the child, who might be less severely impaired, needs more hours… ‘you can change your child’s life’” (Interview 1-11-23). Parents are vulnerable and many may not know how much treatment their children actually need.

Alternatively, they can prioritize the admission of people with severe autism who require high numbers of hours per week (often young children who need early intervention), but maintain low behavior analyst-patient ratios (e.g. 1:25-40). Provider organizations can pocket the difference.

Gaming the reimbursement system in these ways is possible because payers are not able to determine the quality of services provided during any time period – especially in terms of clinical staff-patient ratios or types of learning tasks that occur. Reimbursements are not conditional on minimum standards for staffing or what types of services need to be provided. A number of BCBAs we interviewed are highly critical of the lack of adequate care standards and regulatory oversight in the field (Interview 5-15-23; 5-23-30; 5-30-23). While the ABA Billing Codes recommend a ratio of behavior analyst-patients of 1:10-15 patients for intensive treatment cases, it is not enforceable (ABA Coding Coalition 2022). The Council of Autism Service Providers (CASP), a non-profit organization representing service providers (CASP 2023a), also has published guidelines for ‘best practice’ management, these also are only recommendations (CASP 2023b).

Problematic or fraudulent behavior – of under-provision of services relative to overbilling – is difficult or perhaps impossible for regulators to identify reliably. The billing codes are designed to capture the large range of variation in assessment and treatment procedures for any patient for whom the services are medically necessary. Treatment intensity may range from a few to a large number of treatment hours each week, often for long periods of time (ABA Coding Coalition 2022). Using cost data or deviations from average costs per patient to target offenders is problematic, even within coding categories. As a senior scholar in the field noted, “It would be nigh to impossible to calculate the average cost of ABA services per patient per day, and even if it were possible, that average would be very misleading. That’s mainly because the type and intensity (and therefore cost) of ABA services vary substantially across individuals diagnosed with autism” (Interview 3-1-23).

Incentives to game reimbursement payments exist for all provider organizations, but many providers who started their own companies did so in order to serve their own children and those of other families they knew. They were concerned about high quality care for their children, and they understood the types of ABA services that are needed to produce optimal benefits for them. Private equity partners, by contrast, have financial expertise and financial goals, and seem to know little about ABA services, as illustrated in a story told by Lorri Unumb. At an autism conference involving private equity attendees, a PE partner stood up proudly to caution others not to cut the numbers of professional behavior analysts too much, saying “I know they’re expensive but for every 40 or 50 additional kids you bring on, you got to have another one.” Unumb was ‘horrified’ given the recommended ratio of behavior analyst-patients of 1:10-15 patients for intensive treatment cases (ABA Coding Coalition 2022).

Unumb described the approach taken at the non-profit center that she and her husband founded (Unumb Center for Neurodevelopment, previously the Autism Academy of South Carolina). It grew from 3 clients in 2011 to 200 in 2019, with a staff of 50. It offers ABA services, diagnostic assessments, social skills groups, a gym for regular sports activities, job training, summer programs, and programs for families (Ward 2022). The center has a staffing ratio of one BCBA for every six clients, which allows them to fully engage with the clients, provide intensive supervision to the behavior technicians, and to be in treatment rooms at least 10 percent of their time. The behavior technician/child ratio is typically 1:15. The center only hires college graduates for technician roles.

High staffing levels are also needed because some individuals with autism are diagnosed with mental health and/or medical comorbidities, including anxiety, depression, epilepsy, eating and feeding challenges, gastrointestinal distress, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. This makes the jobs of practitioners extremely difficult. Moreover, almost 30 percent of individuals with autism engage in self-injurious behaviors, such as arm biting and head banging, and almost half with autism wander or bolt from safety (Autism Speaks 2023). Unumb reported that her behavior technicians often wear denim jackets to prevent their skin from being broken by a bite. She emphasized that because the jobs are so demanding, provider organizations must offer high relative wages and benefits, as well as ongoing training, supervision, and emotional support. Otherwise, staff will quit in high numbers.

Another growing concern in the ABA services community is that PE owners are pushing to standardize care, not only through telehealth strategies that emerged during the COVID pandemic, but more generally. Professionals in the field have begun to identify the conditions under which telehealth may be effective – particularly for interactions between behavior analysts and technicians or parents; But many are skeptical about its use for direct care with autistic individuals unless in-person alternatives are not available (CASP 2021). Enthusiasm for telehealth in ABA services, emphasizing its efficiency, also comes from venture capital-backed start-ups such as AnswersNow. According to its CEO, Jeff Beck, “While many in-person clinics recommend 20-40 hours per week of applied behavioral analysis therapy, AnswersNow only asks for four hours….” (Perna 2023).

A number of cases in Appendix A provide evidence of how PE firms have gamed health insurance reimbursement systems through their staffing, care management, and billing practices. Moreover, recall that these examples involve large systems implementing policies that affect thousands of employees and patients.

One example is Hopebridge Autism Therapy, which was bought out by Baird Capital in a 2017 LBO. Baird Capital doubled Hopebridge Autism’s size and sold it in 18 months to PE firm Arsenal Capital in an SBO worth $255M. Arsenal expanded it to some 115 locations in 12 states in three years (Ervin 2022). Then, a 2022 investigative report documented widespread unethical and sometimes abusive behavior, as well as lack of transparency and accountability, as reported by parents and employees. Staff lacked training and supervision; turnover was extremely high. “In all cases, they felt incidents were not properly addressed or investigated and were instead ignored or hidden by the company” (Fry 2022).

Another example comes from our interview with a Registered Behavior Technician employed at LEARN Behavioral after it was taken over in 2019 in a PE firm in a secondary buyout. She reported that benefits fell, they were no longer compensated for additional tasks such as scheduling, they were only paid for ‘face time’ with patients, and if patients canceled, they didn’t get paid at all. “It was a spot market.” Therapists were also pressured not to take time off, and if they did, they were required to make it up (Interview 6-7-2022).

One of the most salient examples of both labor cuts and billing fraud occurred at Centria Healthcare, established by PE firm Capricorn Healthcare (renamed Martis Capital) as a platform in 2016. It became the largest ABA autism provider in Michigan and expanded to nine states from 2016 to 2019. Its staffing and care management policies were documented in a series of investigative reports by the Detroit Free Press, a whistleblower lawsuit, and multiple state investigations. Its staffing policies were to hire unqualified technicians with little background in ABA services and provide little training, leading to over 100 substantiated allegations of abuse, neglect, and use of unwarranted force on children. Its care management policy was standardized in a ‘25 to Thrive Model’ that required at least 25 hours of ABA services per week, regardless of the patient’s condition. Supervisors were pressured under threat of discipline to bill Medicaid 25-40 hours per week. Centria lost its Michigan contracts, but Martis Capital faced no consequences and exited in a 2019 secondary buyout for $415 million to Thomas Lee Partners – a firm with no prior experience in autism or behavioral health services. Centria has since expanded to 13 states (Rochester, Wisely, and Anderson 2018; Wisely and Anderson 2018; Anderson 2019; Olson 2022; PitchBook Centria Profile 2023).

Similarly, at Autism Learning Partners (ALP), employees reported that after the 2010 buyout, training and supervision deteriorated, benefits were cut, experienced management were replaced with people ‘preferred’ by the PE owners, and turnover increased substantially (Olson 2022). Great Point Partners sold the system to FFL Partners in a secondary buyout worth $270 million (Pringle 2018b). Thereafter, employees reported that management created standardized ‘cookie-cutter’ treatment plans, ‘copy-pasted,’ with the same billable hours; they called it ‘a billing machine.’ Parents also report overbilling (Bannow 2022). In 2021, ALP paid almost $1 million to settle former California employees’ allegations that it used a time rounding system that failed to pay workers for all hours worked, including overtime (see Olson 2022, Bannow 2022). By 2022, the ALP system had grown to 3,500 employees in 20 states.

Some PE firms have also bought out ABA provider organizations despite their having a pattern of fraudulent billing practices – something that the due diligence procedures of PE firms should have detected. This is true of the Thomas Lee Partners’ buyout of Centria (above), as well as BlueSprig Pediatrics (owned by KKR), which bought out the Shape of Behavior after the chain was charged with fraud for billing excessive hours on single days and misrepresenting providers’ identities to TRICARE (US DOJ 2021). It paid $2.7M to settle the case in 2021. See also Appendix A, the South Carolina Early Autism Project (Trimaran Partners).

In sum, there is growing case evidence that private equity firms have adopted staffing and care management strategies designed to enhance wealth extraction, with negative consequences for employees, patients, and their families.

The case study of the Center for Autism & Related Disorders provides a more detailed account of how a leveraged buyout by a large generalist private equity firm has affected the quality and availability of autism services. CARD was founded in 1990, and, over 30 years, became one of the largest ABA provider organizations in the country, with some 250 sites and 6,000 employees in 2018 (Pringle 2018c). It was then sold to Blackstone, the world’s largest private equity firm. By 2022, however, Blackstone had cut the number of CARD sites in half – with little notice to families – closing all of the sites in 10 states. In June, 2023, CARD filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection as rumors circulated that it might close additional state markets (Larson 2023b). What happened to CARD under Blackstone’s ownership?

CARD was founded by Doreen Granpeesheh in 1990 after she received a Ph.D., under the direction of psychology professor Ivar Lovaas, doing experimental research on the efficacy of ABA therapy to treat autism. As noted earlier, Lovaas’ research (1987) showed that intensive behavior therapy of 40 hours per week yielded significantly greater improvements in cognitive and behavioral functioning for children with autism, compared to a control group that received only 10 hours or those receiving different types of treatment (Bryant 2021).

Granpeesheh developed a unique curriculum (the CARD Model) based on the UCLA research, and its success led to parental demand for sites in other locations, which Granpeesheh agreed to do if they could organize at least 25 full-time clients – the break-even point to sustain a site (Granpeesheh et al. 2014). The pace of opening sites accelerated after the publication of a 1993 book by the mother of two children with autism who made large improvements with early intensive ABA treatment (Maurice 1993). That book introduced ABA to thousands of parents of children with autism around the world, many of whom began to seek ABA services.

In 2014, Granpeesheh co-authored a comprehensive manual on ABA services based on a detailed description of the CARD model (Granpeesheh et al. 2014). In the 1990s and early 2000s, Granpeesheh’s business strategy was to grow organically at about two-to-five programs a year, slowing the pace as needed to avoid quality control problems (Bryant 2021). An in-house facilities management staff did due diligence to identify locations with enough demand to create sustainable sites. CARD used retained earnings from existing programs to open new ones, remaining debt-free.

To advance effective ABA treatment programs, Granpeesheh established a research department, with staff regularly conducting research and publishing in leading academic journals. To ensure quality control, CARD developed a training program for therapists that included 80 hours of classroom training, 20 hours of practicum, and two exams. Ongoing training and supervision on site occurred through a staffing ratio of one BCBA supervising several paraprofessionals and overseeing the treatment program of roughly 10-15 clients, depending in part on state reimbursement levels. A typical clinic had three therapists and 20-50 part-time paraprofessionals (Granpeesheh et al. 2014). According to one BCBA at the time, “The training program was phenomenal … they offered several months of virtual training focusing on assessment, curriculum design, goal writing and management. After this, all of the trainees in the supervision program were flown to the corporate headquarters in California to receive intensive in-person training from some of the most senior clinicians at the company. …I’ve never seen any company invest so much in its clinicians… CARD technicians were highly sought after… After I completed the technician training, I could have left and made a lot more money elsewhere, but I stayed to participate in the supervision training program…” (Interview 5-15-23).

CARD grew more rapidly after 2010, and added about 100 sites in the 2014-17 period. This level of rapid growth, which positioned it for an eventual sale, had the classic spillover effects of taxing the company’s resources and its ability to maintain its prior levels of staffing, training, and supervision. While these functions were stretched thin during this growth spurt, the corporate training program continued (Interview 4-13-23; 5-29-23).