Report

The Human Consequences of Economic Sanctions

Report

Fact-based, data-driven research and analysis to advance democratic debate on vital issues shaping people’s lives.

Center for Economic and Policy Research

1611 Connecticut Ave. NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20009

Tel: 202-293-5380

Fax: 202-588-1356

https://cepr.net

En español| Sanctions Fact Sheet ![]() |Version in Journal of Economic Studies

|Version in Journal of Economic Studies

The author thanks Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, Joy Gordon, Dorothy Kronick, George Lopez, Alex Main, and Mark Weisbrot for comments and suggestions and Dan Beeton, Jacques Bentata, Giancarlo Bravo, Luisa García, Jonea Gurwitt, Camille Rodríguez, Gabby Rosazza, and Aileen Wu for editorial and research assistance.

This paper provides a comprehensive survey and assessment of the literature on the effects of economic sanctions on living standards in target countries. We identify 32 studies that apply quantitative econometric or calibration methods to cross-country and national data to assess the impact of economic sanctions on indicators of human and economic development. Of these, 30 studies find that sanctions have negative effects on outcomes ranging from per capita income to poverty, inequality, mortality, and human rights. We provide in-depth discussions of three sanctions episodes — Iran, Afghanistan, and Venezuela — that illustrate the channels through which sanctions affect living conditions in target countries. In the three cases, sanctions that restricted the access of governments to foreign exchange limited the ability of states to provide essential public goods and services and generated substantial negative spillovers on private sector and nongovernmental actors.

This paper provides a comprehensive survey and assessment of the literature on the effects of economic sanctions on living standards in target countries. We identify 32 studies that apply quantitative econometric and calibration methods to cross-country and national data in order to assess the impact of economic sanctions on indicators of human and economic development and human rights. Of these, 30 studies find that sanctions have negative effects on outcomes ranging from per capita income to poverty, inequality, mortality, and human rights. We also provide in-depth discussions of three sanctions episodes — Iran, Afghanistan, and Venezuela — that illustrate the channels through which sanctions damage living conditions in target countries. In the three cases, sanctions that restricted governments’ access to foreign exchange affected the ability of states to provide essential public goods and services and generated substantial negative spillovers on private sector and nongovernmental actors.

The use of economic sanctions by some of the world’s most important economies has significantly increased in recent decades. Their adoption is almost invariably framed in the context of attempts to deter or dissuade target governments and individuals from actions that purportedly would undermine global security, democracy, or human rights. While a considerable body of research has investigated the effectiveness of sanctions in achieving their intended objectives, much less effort has been devoted to understanding the implications of sanctions for persons living in target countries.

This paper reviews the current state of knowledge regarding the human consequences of economic sanctions. We discuss the effect of sanctions on socioeconomic conditions in target jurisdictions, including on the economy, poverty and distribution, health and nutrition, and human rights. We provide a systematic survey of the empirical literature using both cross-country panel and country-level data sets. We find a remarkable level of consensus across studies that sanctions have strongly negative and often long-lasting effects on the living conditions of most people in target countries.

We supplement this discussion with case studies that illustrate the channels through which sanctions have affected living conditions in three target states: Iran since 1979, Afghanistan since 1999, and Venezuela since 2017. These case studies help us to look more closely at the main channels through which sanctions affect the economy and living standards. They also illuminate why safeguard mechanisms, such as humanitarian exceptions, fail to offset these collateral effects.

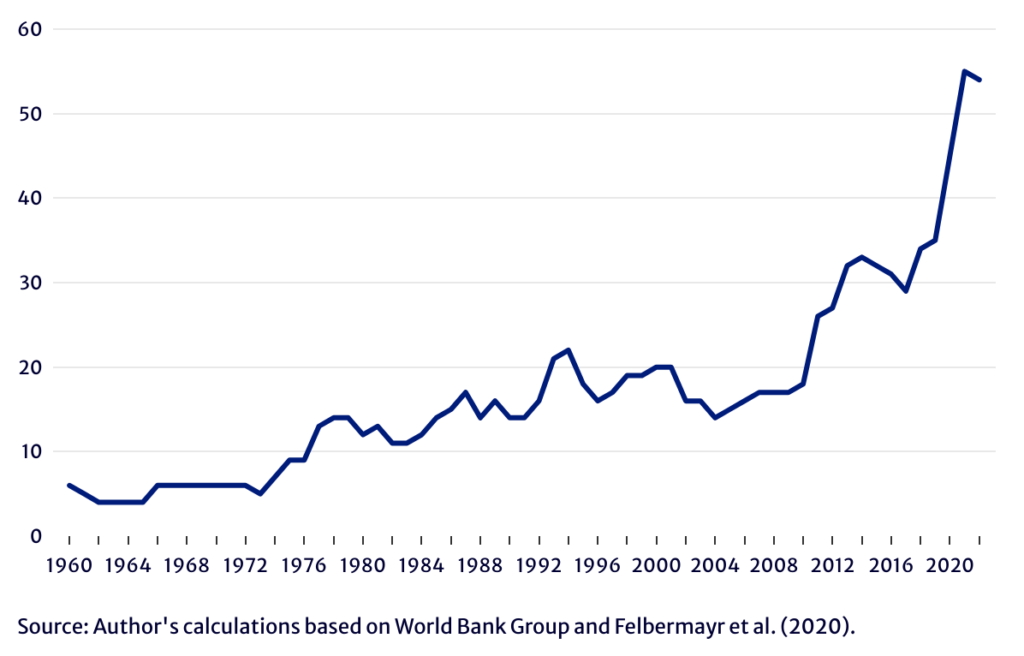

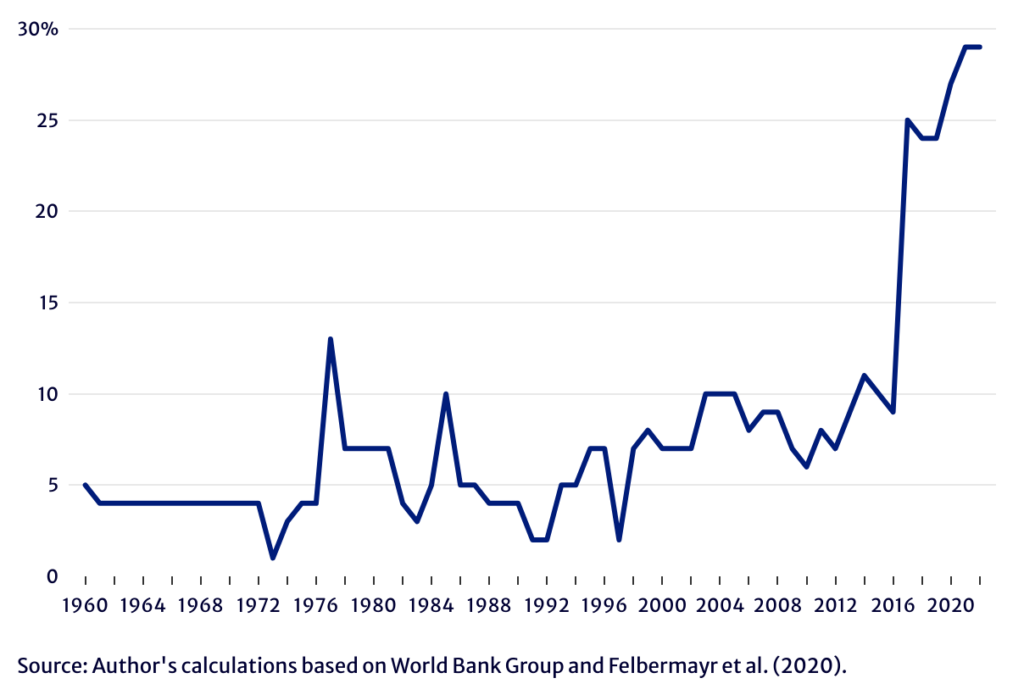

Over the past six decades, there has been significant growth in the use of economic sanctions by Western powers and international organizations. Less than 4 percent of countries were subject to sanctions imposed by the United States, European Union, or United Nations in the early 1960s; today, that share has risen to 27 percent. The magnitudes are similar when we consider their impact on the global economy: the share of world GDP produced in sanctioned countries rose from less than 4 percent to 29 percent in the same period. In other words, more than one fourth of countries and nearly a third of the world economy is now subject to sanctions by the UN or Western nations.

There is also a clear rising trend in individual or entity-specific sanctions. During the first Obama administration, there was an average of 544 new designations to the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s (OFAC) list of Specially Designated Nationals (SDNs). That number rose to 975 per year in the Trump administration and has continued rising so far (to 1151 per year) in the Biden administration.

Recent years have seen increasing concern about the continuing humanitarian effects of sanctions. In 2014, the Human Rights Council of the United Nations adopted a resolution stating it was “deeply disturbed by the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures” and “alarmed by the disproportionate and indiscriminate human costs of unilateral sanctions and their negative effects on the civilian population.”

Nevertheless, it appears clear that some of the economic and humanitarian impact of sanctions on target populations is intended. For example, a statement issued by the UK government after freezing Russian central bank assets in February 2022 stated unambiguously that “sanctions will devastate Russia’s economy.” In February 2019, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated in response to a question about the effects of sanctions on Iran, “Things are much worse for the Iranian people, and we are convinced that will lead the Iranian people to rise up and change the behavior of the regime.”1 Pompeo made similar statements about US sanctions in Venezuela the following month.2

From another perspective, the chair of the US House Rules Committee, Congressman Jim McGovern, wrote to President Biden in May 2021, asking him to “lift all secondary and sectoral sanctions imposed on Venezuela by the Trump Administration.” In the letter, he noted:

…the impact of sectoral and secondary sanctions is indiscriminate, and purposely so. Although U.S. officials regularly say that the sanctions target the government and not the people, the whole point of the “maximum pressure” campaign is to increase the economic cost to Venezuela… Economic pain is the means by which the sanctions are supposed to work.… it is not Venezuelan officials who suffer the costs. It is the Venezuelan people. Credible sources have consistently found that sanctions have worsened the humanitarian crisis in the country.3

Our study summarizes the results of 32 research papers and book chapters that use econometric or general equilibrium calibration methods to assess the effects of economic sanctions on living conditions in target countries. This includes 20 studies that use cross-country panel data and 12 studies that use within-country time series or firm-level data. Nineteen of the 20 cross-country papers find consistently statistically significant adverse effects of economic sanctions on the dependent variable of interest. These include per capita income, poverty, inequality, international trade, child mortality, undernourishment, life expectancy, and human rights. One paper finds ambiguous effects of sanctions on human rights, with sanctions leading to deteriorating rights in some specifications and improvement in others. Eleven of the 12 country-level studies find negative effects on similar outcome variables. The only country study that finds the contrary result is a study using Venezuela time series import data, which we discuss in detail below.

Put together, these studies constitute an impressive array of evidence on the negative effects of both broad economic and narrowly aimed sanctions on living conditions in target countries, with most results indicating strong adverse effects and only a handful of nonsignificant results. Nevertheless, there is clearly room for more research to identify the causal mechanisms at work, as the publications surveyed were mostly written during a period in which there have been significant advances in the measurement of sanctions and evaluation of causal effects.

This paper also provides recent case studies of three economies subject to sanctions barring, or significantly impeding, international economic transactions: Iran, Afghanistan, and Venezuela. The purpose of these case studies is to provide a clearer understanding of the mechanisms through which sanctions affect living conditions in target economies, as well as how these have evolved in the recent past. For this reason, we focus on three cases in which sanctions are still in force and that can help us observe how recent developments that may not be adequately captured by cross-national data — such as the shift to personal sanctions, or the proliferation of humanitarian exceptions — have affected vulnerable groups in target economies.

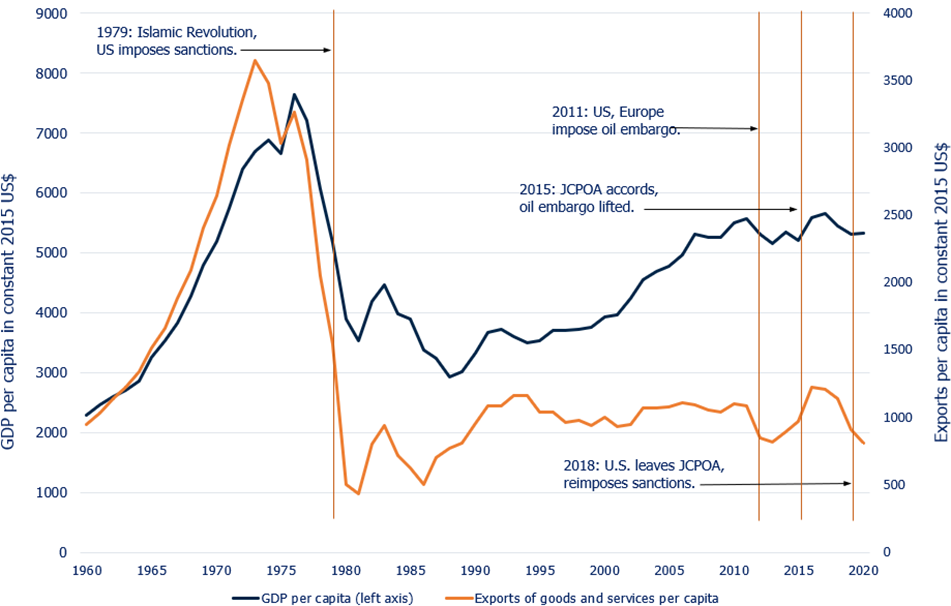

United States sanctions on Iran were first enacted in response to the November 1979 takeover of the US Embassy in Tehran. To this date, the 1979 Executive Order finding that the situation in Iran constituted an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security” of the United States remains the longest-standing US national emergency declaration. Since the United States was, by far, Iran’s largest trading partner before the revolution, the trade embargo caused significant losses. US-Iran trade collapsed immediately after the sanctions and never recovered to its previous levels, even during periods in which sanctions were eased.

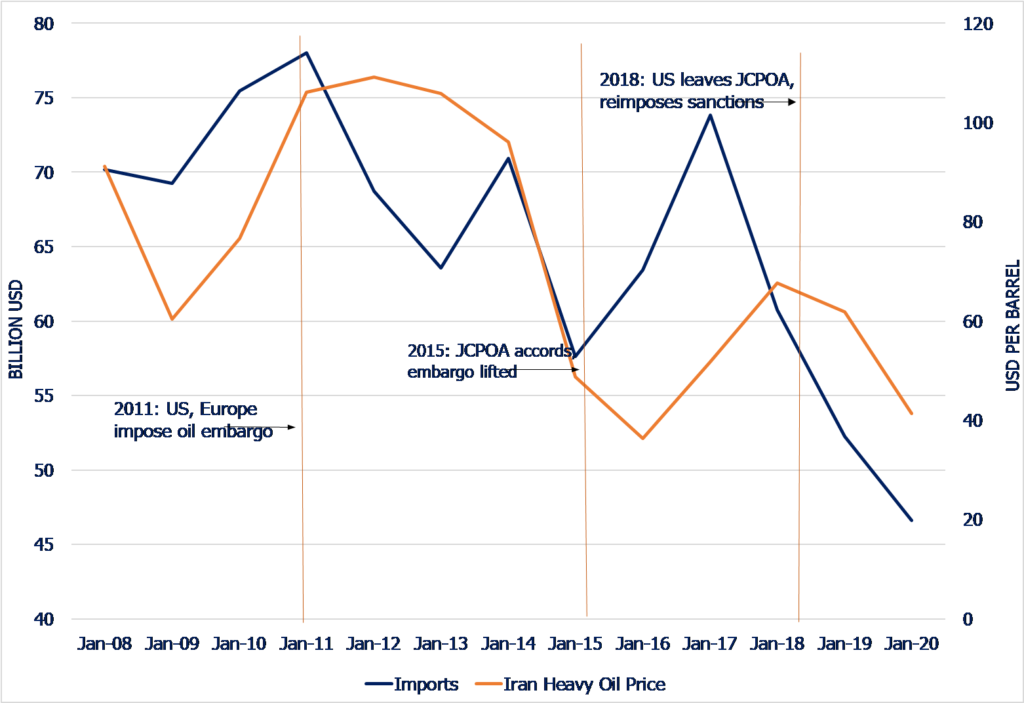

The support for multilateral sanctions on Iran was bolstered when evidence surfaced in 2002 of Iran’s construction of two secret research facilities for producing enriched uranium and heavy water. Starting in 2006, the United Nations Security Council approved a series of resolutions freezing the assets of entities and persons involved in Iran’s nuclear program, prohibiting the transfer of nuclear items to Iran, and calling for restraint and vigilance on financing involving Iran and transactions with Iranian banks, including the Central Bank. Predictably, these decisions resulted in stronger compliance obligations for global financial institutions, which then had to guarantee that their operations with Iran were not supporting these banks or proxies for listed Iranian entities. Starting in late 2011, the United States and Europe imposed additional restrictions that led to the banning of the importation of all Iranian crude oil and petroleum products into Europe and the imposition of secondary US sanctions on other countries that did not commit to reducing Iranian oil imports.

The sanctions were lifted as a result of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), in which Iran agreed to the progressive reduction of its enriched uranium stockpile and enrichment operations. In May 2018, however, the Trump administration withdrew the United States from the JCPOA and reinstated all sanctions on Iran. While the Biden administration has participated in negotiations attempting to revive some version of the JCPOA, these efforts have been unsuccessful so far.

Iran’s GDP, oil production, and export data time series clearly display marked declines following each round of sanctions. They also show some evidence that the economy has progressively become more resistant to the damage from sanctions. Studies using synthetic control methods confirm that sanctions have negatively affected Iran’s economy compared to the counterfactual that would have been expected in a no-sanctions scenario. Alternatively, calibration exercises based on partial or computable general equilibrium (CGE) models also find negative effects on living standards.

The data are strongly consistent with the hypothesis that the bulk of changes in Iran’s growth performance has been driven by changes in oil exports and production, changes that were strongly affected by sanctions. Imports declined strongly in the aftermath of both the 2011 and the 2018 sanctions, and recovered strongly after the JCPOA accords. Studies using household survey data find that rural households, belonging to low- and middle-income groups, or those headed by old and unemployed persons, had the highest likelihood of moving into poverty in the sanctions period, while households working in the public sector and those headed by highly educated persons were least likely to move into poverty.

Aside from their effects on income and poverty, there is evidence that sanctions significantly affected non-income dimensions of well-being such as health. There were shortages of 73 drugs in Iran during the sanctions period; 32 were also on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines. Seventy of the 73 scarce drugs fell under an OFAC general license to export drugs to Iran, suggesting that this type of authorization has little practical effect. There is abundant anecdotal evidence that imports of some approved medicines have been blocked. For example, a $60 million order to an American pharmaceutical company for an antirejection drug for liver transplants failed to reach Iran, despite having all the required OFAC licenses, because no bank would perform the transaction.

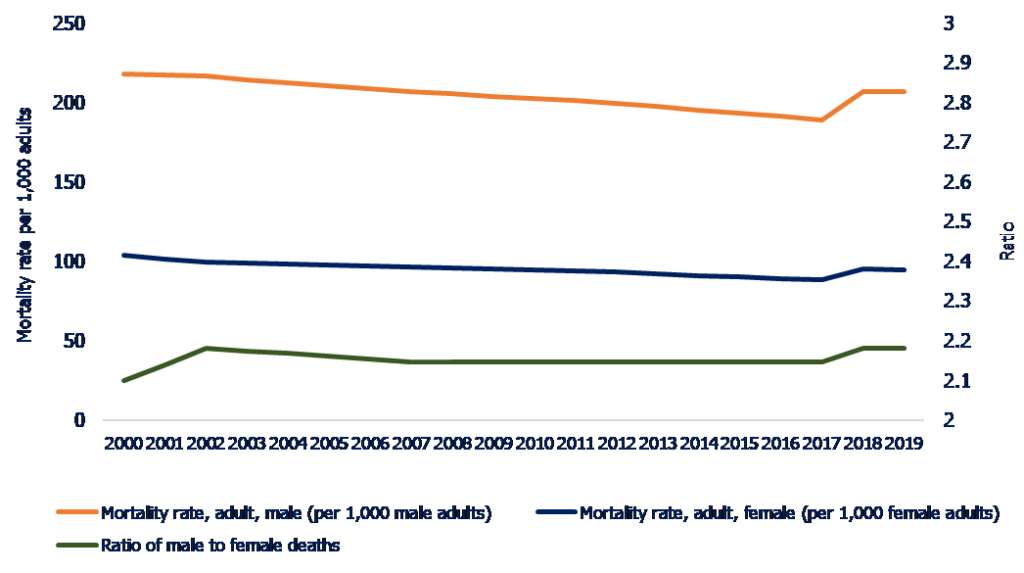

We also find that progress in reductions of mortality, stunting, and female anemia stalled considerably during the sanctions period and resumed after sanctions were lifted. Data from the Global Burden of Disease Study show a significant slowing of the rate of decrease of age-standardized disability-adjusted life years after 2011, with the most detrimental effects concentrated on noncommunicable diseases.

In Afghanistan, restrictions on international economic transactions date from the rise of the Taliban to power in 1996, after the prolonged civil war. The decision of almost all countries to withhold recognition of the Taliban government functioned as de facto sanctions by impeding officials from accessing assets or entering into contracts as representatives of the Afghan state. For this reason, neither the UN resolutions nor the US executive orders imposing sanctions refer explicitly to the government of Afghanistan, as there is no formally recognized Afghan government to sanction. Nevertheless, because the Taliban controlled virtually all Afghan state institutions from 1996 to 2001, sanctions on the Taliban effectively blocked access to any foreign assets and limited the ability of the Afghani government to engage in trade. A case in point: the Afghan government was unable to claim control over $254 million in gold reserves held by Da Afghanistan Bank (DAB), the Afghan central bank, at the US Federal Reserve.

Because nonrecognition acts as a de facto imposition of sanctions on a government, it makes little sense to draw a distinction between the timing of accession of the Taliban to power in Afghanistan in 1996 and the imposition of sanctions three years later. Any meaningful economic interactions between the Taliban government and other states or international organizations were precluded as of 1996. It is of course difficult to construct a counterfactual as to what economic relations with the rest of the world would have been if the Taliban had been recognized as Afghanistan’s government and sanctions not been imposed.

Furthermore, there are serious data limitations on any attempt to evaluate the aggregate performance of Afghanistan’s economy during the period of Taliban rule or to disentangle the effect of sanctions from that of Taliban rule. Aggregate data collection appears to have effectively ceased long before the Taliban takeover, generating a paucity of statistics on relevant human development outcomes. United Nations estimates indicate a decline of 76 percent in real per capita incomes between 1986 and 2001, which would put it in line with the largest economic growth collapses observed in modern world history.

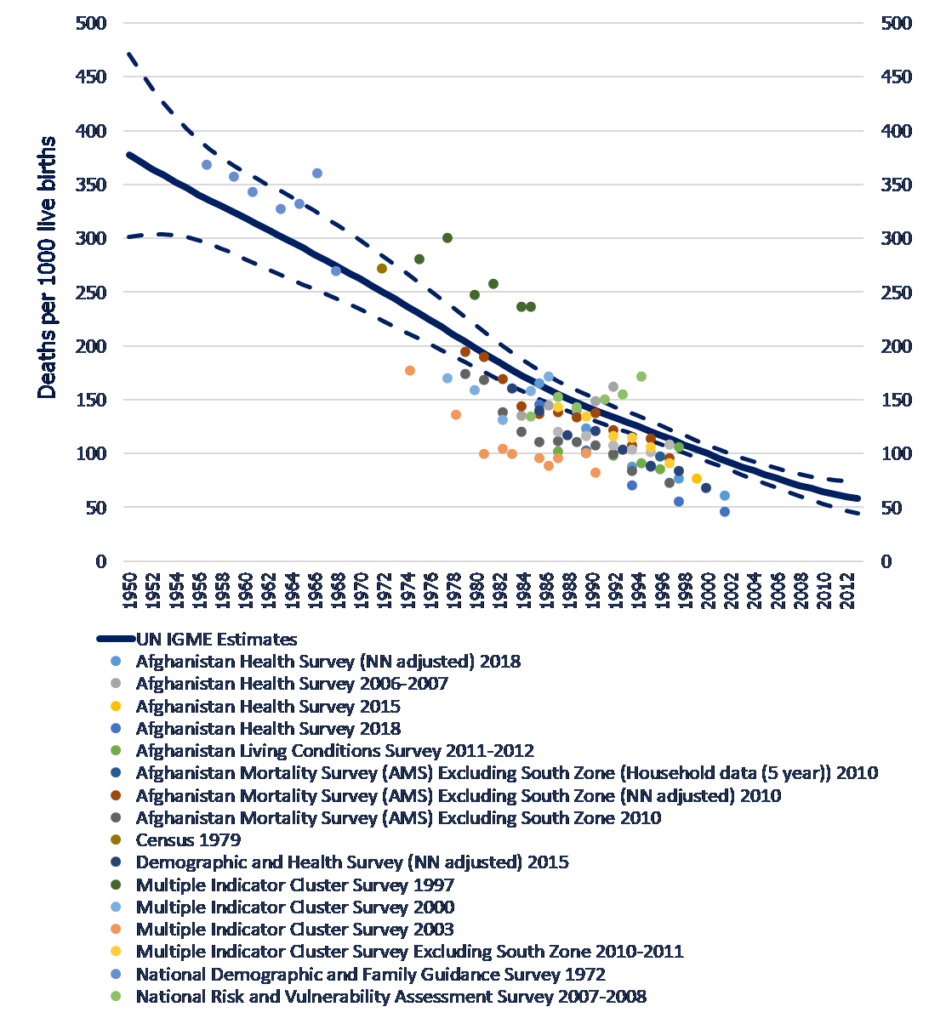

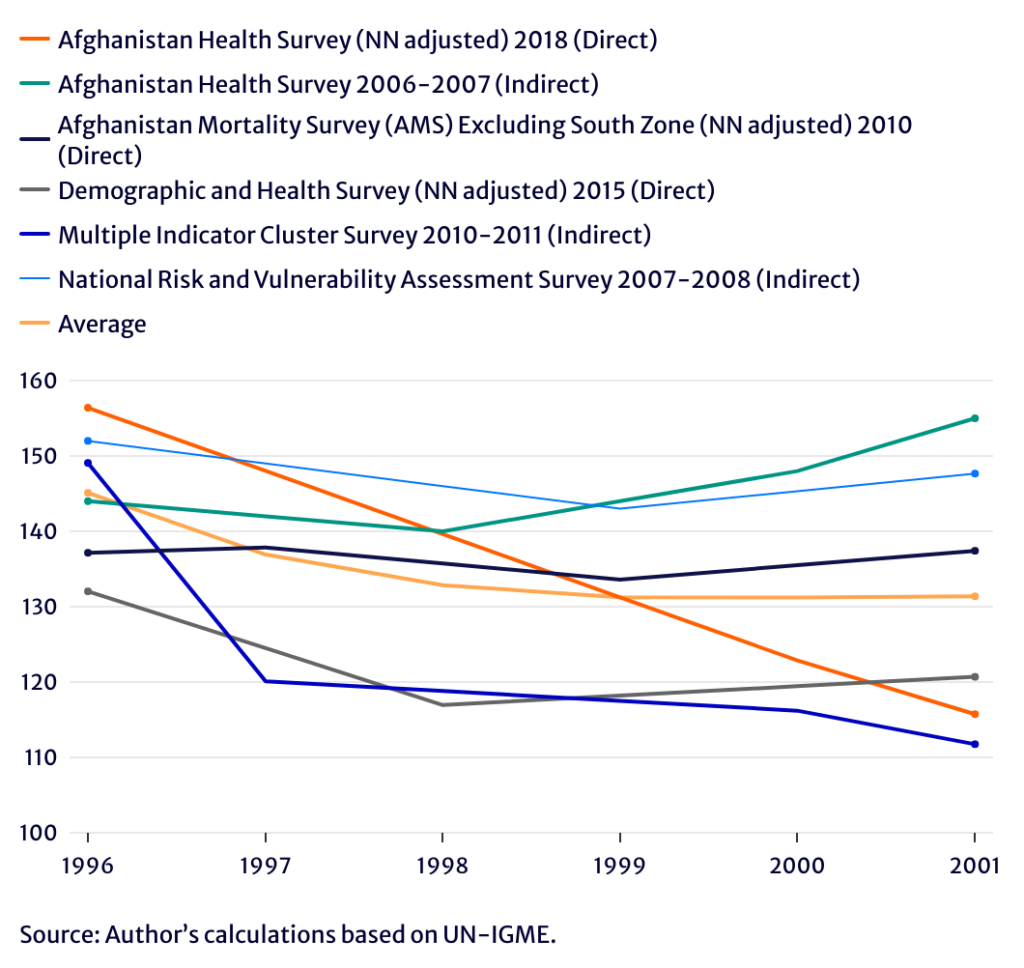

Education data, despite being quite sparse, show a consistent picture of declining school enrollments, as well as a near-disappearance of female schooling during the 1996–2001 period, as the Taliban applied a nationwide ban on female education and children were increasingly recruited as combatants in the ongoing civil war. Data on infant mortality are more equivocal, partly because of the pervasive use of statistical extrapolation methods by UN agencies. Yet, it is at least consistent with the hypothesis that child mortality rates rose during the period of Taliban rule, and especially in the last two years, which included the formal imposition of sanctions and the US invasion.

Nongovernmental organizations and UN agencies were highly critical of the effect of sanctions at the time. A 2000 study commissioned by the Office of the UN Coordinator for Afghanistan concluded that UN sanctions had a tangible direct effect on the Afghan economy as well as a substantial indirect impact on the humanitarian situation. On the eve of the adoption of new sanctions by the UN Security Council in December 2000, Doctors Without Borders warned that sanctions would be devastating for a country without a functioning health care system. Even UN Secretary-General Kofi Anan seemed to lament the thrust of the resolution, stating before its adoption that it “is not going to facilitate our humanitarian work.”

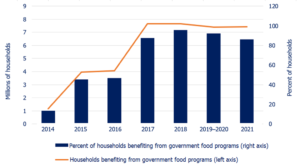

The Taliban returned to power in 2021 after a major offensive that followed the withdrawal of US troops. Because both UN and US sanctions aimed at the Taliban had never been lifted, these went into force immediately, restricting any interactions with the new Afghan authorities. Similar to the situation 20 years earlier, lack of formal recognition of the Taliban government mimics the effect of government sanctions, impeding the carrying out of international legal, commercial, or financial transactions involving the Afghan government. The blocking of access to the country’s central bank assets plays an even greater role this time around. The Central Bank now has lost access to significantly larger holdings, valued at $9.6 billion, or the equivalent of nearly half the country’s GDP, and around 18 months of imports. These were effectively confiscated by the United States ($7 billion) and Europe in August 2021, after the Taliban took power.

In February 2022, President Biden formally blocked all Afghanistan central bank reserves held in the United States and issued a license enabling the transfer of half ($3.5 billion) of these to a trust fund, which was said to ensure that the money will be used for the benefit of the Afghan people. The trust fund is managed by a foundation created by Afghan nationals whom the US has accredited as representatives of the Afghan government based on their appointments to central bank management positions prior to the Taliban’s takeover of power.

Major international human rights and humanitarian groups have condemned the confiscation of more than $7 billion in assets belonging to DAB.4 John Sifton, the Human Rights Watch Asia advocacy director, said, “restrictions on the banking system of Afghanistan are really intensifying the country’s already serious human rights crisis. And they’re driving populations into famine.” David Miliband, a former UK foreign secretary and current president and CEO of the International Rescue Committee, told the US Senate: “The proximate cause of this starvation crisis is the international economic policy, which has been adopted since August and which has cut off financial flows not just to the public sector, but in the private sector in Afghanistan as well.”5 Sanctions and the blocking of access to external assets clearly exacerbate the contractionary effects of the reduction in foreign exchange inflows. Lack of access to international reserves and to emergency international assistance deprives the country of the means to stabilize its economy by smoothing external adjustment, and imposes significant costs on humanitarian agencies that would choose to remain involved despite the change in authorities. They also significantly complicate remittance transfers, which accounted for nearly $800 million in foreign currency inflows prior to the Taliban takeover.

While the Biden administration has issued a set of licenses to facilitate humanitarian transactions with the Afghan government, the licenses do not authorize contracting for services with government institutions, thus permitting interaction with the government only to the extent that it is incidental to third-party transactions. There are numerous examples, both before and after the issuance of these licenses, of sanctions constraining or impeding transactions that could have helped alleviate the Afghan crisis.

Broad economic sanctions, beginning with limitations on financing, were first imposed on Venezuela in 2017, when the Trump administration barred financing and dividend payments to Venezuela’s government and state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA). The US also used personal sanctions — first selectively imposed by the Obama administration in 2015 — to target top government officials and political figures as well as private-sector actors believed to be connected with the Maduro government. Since these designations preclude dealing with designated persons in their official capacity, they essentially brought to an end all interactions with the Venezuelan government not previously authorized by the US government.

In August 2017, President Trump issued an executive order prohibiting the purchase of new debt issued by the Government of Venezuela or by PDVSA, forcing Venezuela to default on existing obligations and impeding a restructuring of Venezuelan debt. The order also barred dividend payments to Venezuela, impeding the government from using profits from its offshore subsidiaries to fund its budget. In January 2019, the US barred trade with Venezuela’s state-owned oil monopoly and recognized Juan Guaidó as the country’s interim president, transferring to his administration control of all of Venezuela’s offshore assets under US jurisdiction. In February 2020, the US sanctioned two subsidiaries of the Russian energy company Rosneft that at the time were handling around 75 percent of Venezuela’s oil sales and the near totality of its gasoline imports. Venezuela began to suffer severe gasoline shortages shortly after Rosneft halted all trade with it and divested from its Venezuela operations in response to the sanctions.

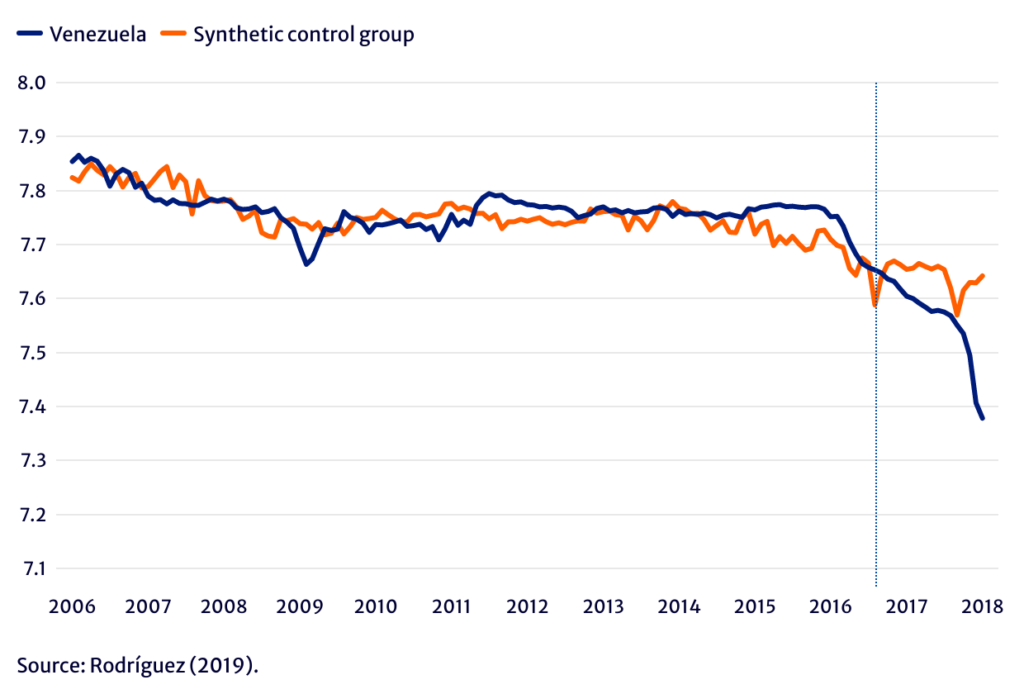

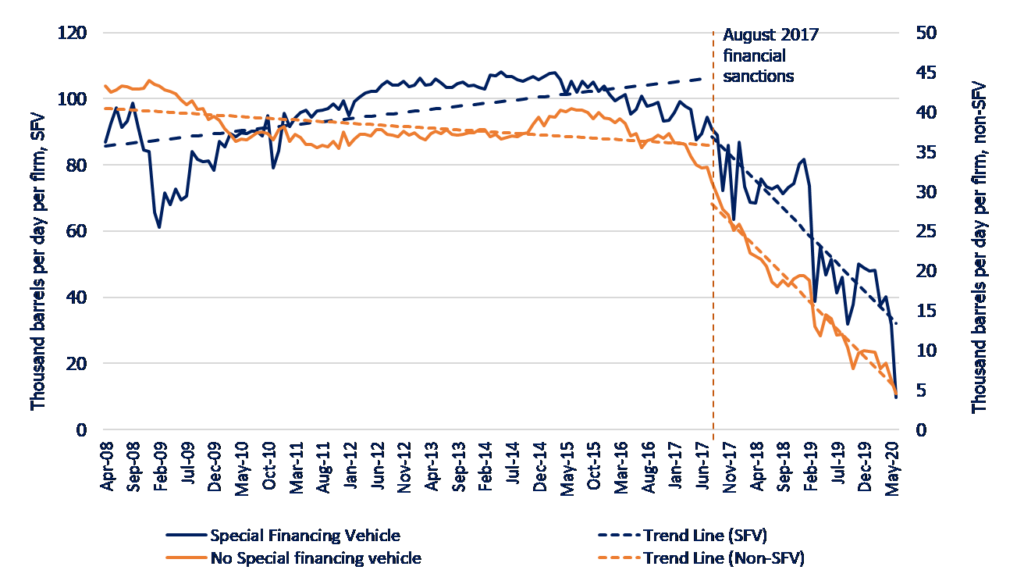

Each round of sanctions (2017 financial, 2019 primary oil, and 2020 secondary oil) was followed by a decline in Venezuelan oil production, which, as measured by independent agencies, had been stable for an eight-year period starting in 2008. Though it had begun to decline in early 2016, prior to the 2017 economic sanctions, this decline appears to have been a consequence of the collapse in oil prices that occurred at the time and affected most other high-cost producers. But even when oil prices began to recover in 2017, Venezuela’s oil production accelerated its decline even as production stabilized or recovered in comparable economies.

Studies using trend interruption estimates and synthetic control methods all confirm that the adoption of sanctions was associated with a decline of oil production compared to a no-sanctions counterfactual. The range of estimates of these studies puts the cost of the decline at between $13 and $21 billion a year, or between two and three times the 2020 level of exports. These results are confirmed by a recent study using firm-level data to compare firms that had access to external finance at the time of sanctions with those that lacked that access. The estimates show that financial sanctions significantly affected the growth of firms with prior access to finance, explaining around 46 percent of their loss of production.

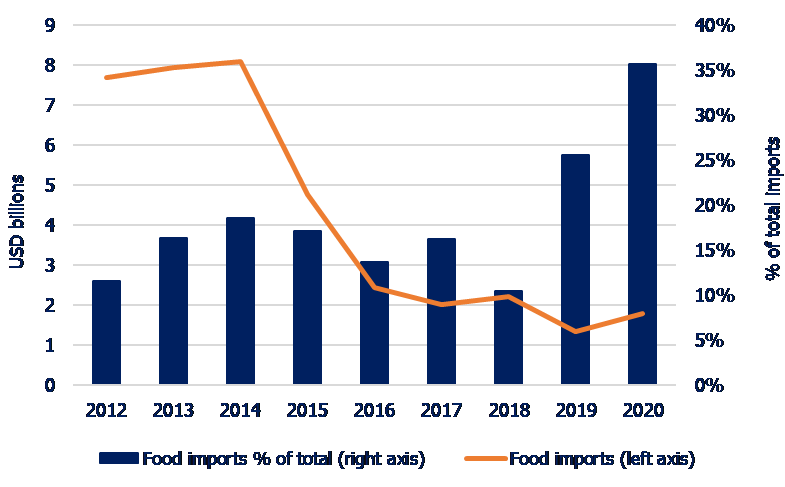

The resulting decline in oil exports severely circumscribed the ability of a traditionally import-dependent economy to buy imports of food as well as intermediate and capital goods for its agricultural sector, driving the economy into a major humanitarian crisis. Total imports fell by 91 percent, while food imports declined by 78 percent. The decline in the economy’s capacity to import made it impossible to maintain past levels of essential goods. Even if Venezuela were importing only food today (i.e., if it had decided to reduce to zero all other imports, including other essentials as well as capital and intermediate goods for its oil industry) it would not be able to pay for more than four-fifths of the food it imported in 2012.

Venezuela’s deep deterioration in indicators of health, nutrition, and food security occurred alongside the largest economic collapse, outside of wartime, since 1950. The collapse in oil revenues drove the economic contraction, which caused the deterioration in socioeconomic indicators. By contributing to lowering the country’s oil production, sanctions also contributed to lowering per capita income and living standards, and are a key driver of the country’s health crisis, including its increase in child and adult mortality.

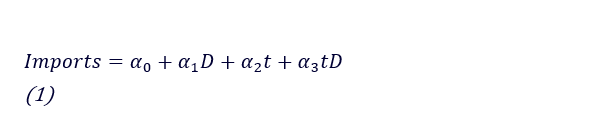

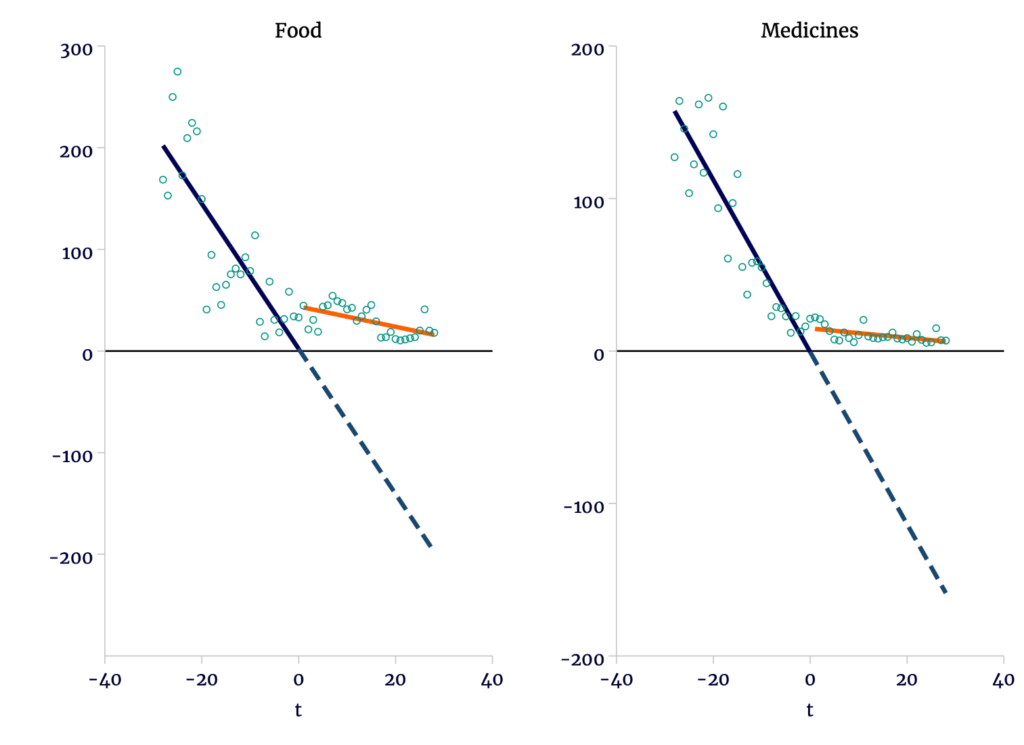

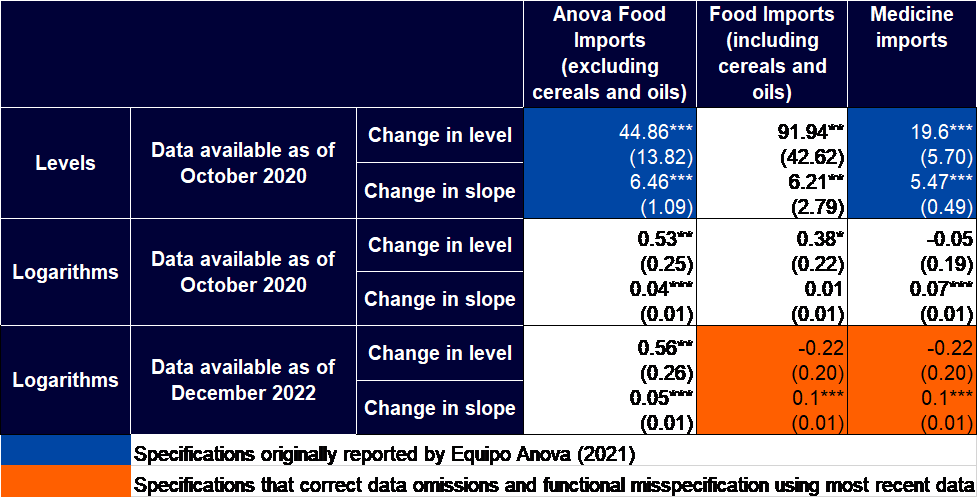

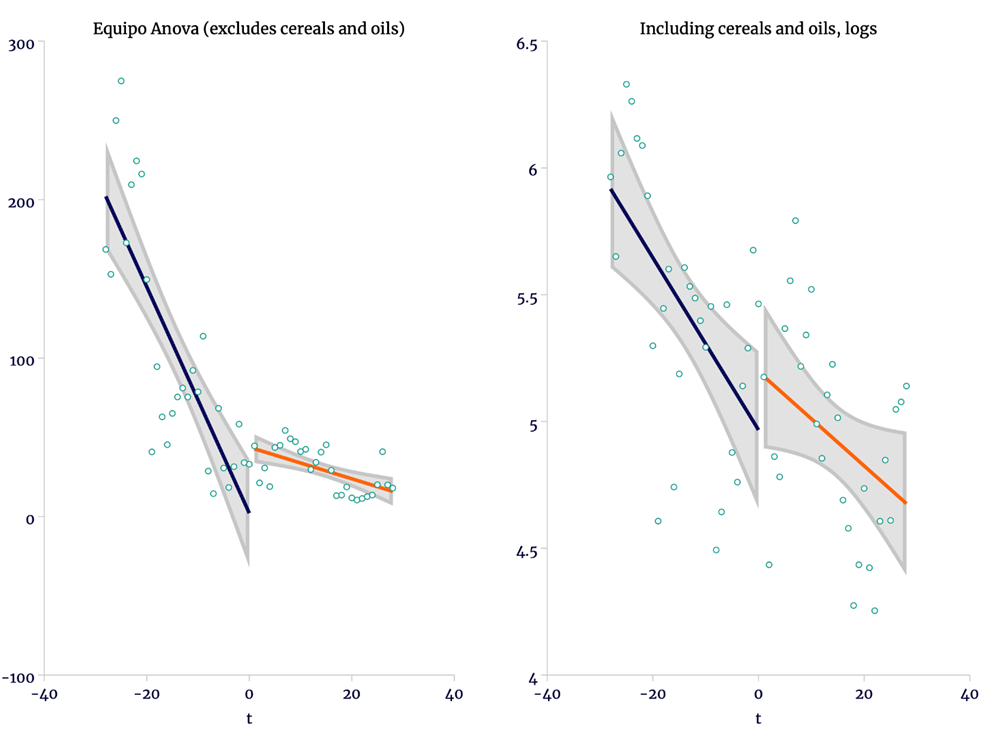

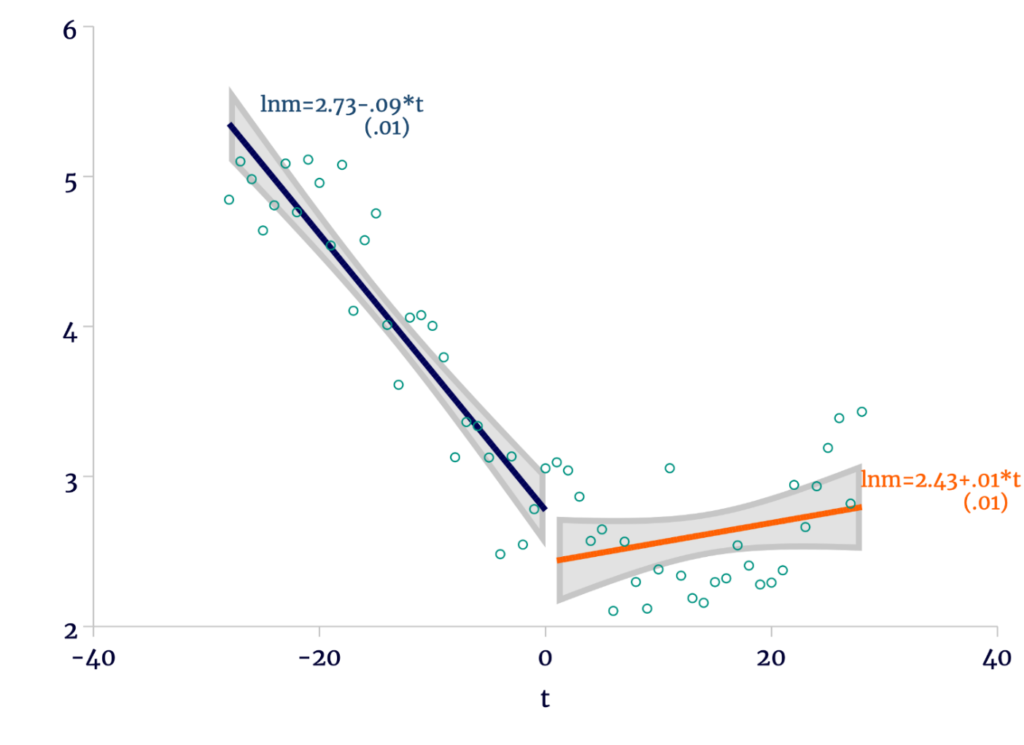

Only one study disputes this conclusion. A policy brief published in January 2021 by ANOVA, a Venezuelan consultancy firm with links to the country’s opposition, argues that sanctions were followed by an improvement in imports of essentials, reflecting the positive effects of sanctions-induced economic liberalization. This is also the sole paper in our survey that contends that sanctions are associated with an improvement in living standards. The argument is based on the alleged finding of a break in trend at the time of the imposition of the August 2017 sanctions in ordinary least squares time series regressions that model food and medicines imports as a function of time. The study has been widely reported in the Venezuelan press and is often invoked by pro-opposition leaders and influencers.

We replicate the ANOVA results and find that they are due to an artifact of several questionable modeling choices and at least one crucial coding error. These include the choice of an arbitrary bandwidth that is three times as large as that chosen by methods standard in the literature on regression discontinuity, the specification of the dependent variable in absolute US dollars instead of the more conventional logarithmic specification used in macroeconomic time series studies, and the omission of several import categories accounting for around four-fifths of the economy’s food imports at the time of sanctions. Once these errors are corrected, any evidence of an improvement in the level or rate of change in food imports disappears. Neither close inspection of the corrected data nor a battery of statistical tests shows evidence of any sustained significant improvement in food or medicines imports following the 2017 financial sanctions.

The evidence surveyed in this paper shows that economic sanctions are associated with declines in living standards and severely impact the most vulnerable groups in target countries. It is hard to think of other cases of policy interventions that continue to be pursued despite the accumulation of a similar array of evidence of their adverse effects on vulnerable populations. This is perhaps even more surprising in light of the extremely spotty record of economic sanctions in terms of achieving their intended objectives of inducing changes in the conduct of targeted states.

Attempts to redesign the sanctions regime, some of which are without doubt well-intended, can easily become distorted because of perverse policymaker incentives. Largely ineffective humanitarian exceptions are often used to falsely claim that sanctions do not impede or create obstacles to humanitarian assistance. By design or by omission, regulatory ambiguity generates incentives for generalized de-risking by private-sector actors — who can cause considerable damage to the economy and population by avoiding various commercial interactions with sanctioned countries even if there are “exceptions” that would allow them. These “exceptions” allow officials to characterize the problem as one of “over-compliance” rather than one of inadequate institutional design.

Regrettably, the populations most affected by sanctions are also voiceless in decisions about their adoption. Often, the decision to adopt or tighten sanctions responds to domestic political incentives in sanctioning countries, such as the electoral relevance of politically active diasporas in US swing states. Expanding the space of reasoned and critical public debate will be indispensable to revert this imbalance in the power to decide on the adoption of policies that can harm the lives of millions of people and cause the death of many thousands.

Recent decades have seen a significant increase in the use of economic sanctions by some of the world’s most important economies. While there is ample variation in the contexts and specific goals pursued by sanctioning governments, their adoption is almost invariably framed as part of an attempt to deter or dissuade target governments and individuals from actions claimed to undermine global security, democracy, or human rights. Among the most prominent uses of sanctions in recent times are those aimed at the governments of Iran, North Korea, Russia, Cuba, and Venezuela.

A considerable body of research has investigated the effectiveness of sanctions in achieving their intended objectives. By and large, this literature finds that sanctions usually fail to generate the sought-for changes in the conduct of their targets. And while less effort has been devoted to understanding the implications of sanctions for the persons living in target countries, it is often considered a sign of effectiveness when they harm the targeted economy. That has led to growing concern regarding the consequences of economic sanctions on vulnerable groups in target countries, and it is increasingly common to find sanctions regimes accompanied by a plethora of humanitarian exceptions ostensibly designed to help mitigate or offset the collateral effects of economic restrictions.

This paper reviews the current state of knowledge regarding the human consequences of economic sanctions. We discuss the effect of sanctions on socioeconomic conditions in target jurisdictions, including their effect on the economy, poverty and income distribution, health, mortality, nutrition, and human rights. To do this, we provide a systematic survey of the empirical literature using both cross-country panel and country-level data sets. We find a remarkable level of consensus across studies in the conclusion that sanctions have strongly negative and often long-lasting effects on the living conditions of the majority of people in target countries.

We supplement this discussion with three case studies that illustrate the channels through which sanctions have affected mortality and living conditions in target states: Iran since 1979, Afghanistan since 1999, and Venezuela since 2017. These case studies help us to look more closely at the main channels of causation through which sanctions affect the economy and living standards as well as why safeguard mechanisms such as humanitarian exceptions often fail to offset these collateral effects.

We begin, in section 2, with a review of the evolution of the use of sanctions and how their design has varied in attention to concerns about their collateral effects. Section 3 goes on to discuss the results of research using cross-country panel data to assess the impact of standardized measures of sanctions on outcome variables such as income, health, or human rights. Section 4 analyzes in detail the cases of Iran, Afghanistan, and Venezuela. Section 5 provides concluding comments.

A long historical tradition traces the use of sanctions to at least the fifth century BCE, when the city-state of Athens barred ships from neighboring Megara from accessing its ports in response to Megara’s military actions against Athenian allies. The resulting standoff led to the Peloponnesian War, which ended in a devastating defeat for Athens and the end of Athenian democracy. Ironically, the first documented instance of sanctions is also an example of spectacular failure.

Nevertheless, sanctions were commonly seen as a complement to military strategy up to recent times, with their more extreme form being that of siege warfare. Thus, their consequences on civilian populations were both understood and intended. In the aftermath of World War I, world powers began conceptualizing sanctions as a possible alternative to military action.6 US president Woodrow Wilson, a staunch believer in the ability of sanctions to hold together a new world order, described sanctions as “something more tremendous than war.”7 Sanctions were incorporated in Article 16 of the covenant of the League of Nations, which sought to dissuade members from settling disputes through force by threatening the complete severing of trade and financial relations. In 1935, the League of Nations condemned Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia and imposed an economic and financial embargo on Italy in response; Italy refused to back down and maintained its occupation until its defeat in World War II.8

Sanctions became increasingly common in the postwar period and were used for purposes as diverse as isolating the white-rule government of Southern Rhodesia (1966–1979), responding to the Soviet Union’s occupation of Afghanistan (1979–1981), and punishing Argentina’s exercise of its territorial claim in 1982 over the Falkland/Malvinas Islands. Among the most controversial applications were sanctions imposed by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on Iraq after its invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Concerns about sanctions causing a widespread humanitarian crisis in Iraq led to the launch of the Oil-for-Food Program in 1996 in an attempt to mitigate the consequences on Iraqi living standards.9

Growing awareness of the unintended consequences of sanctions on civilians and third parties led to a call for the development of “smart sanctions” more directly aimed at the actors whose change of conduct was sought.10 The revamp of sanctions policy spurred the emergence of vast national and international regulatory architectures that aimed to identify wrongdoers and impose selective measures to constrain their economic transactions.11 While blanket embargoes persist in some cases, it is increasingly common for sanctions regimes to focus on barring individuals and entities from international travel or from conducting international financial or commercial transactions. Regardless of whether they are imposed by the United Nations, multinational organizations, or other countries, economic sanctions today are almost invariably accompanied by humanitarian exceptions, though the effectiveness of these exceptions is often questioned.

Broadly speaking, there are two levels of legal frameworks for the imposition of sanctions. Articles 39 and 41 of the United Nations Charter empower the UNSC to adopt “measures not involving the use of armed force” in response to the existence of “any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression.” While the powers granted to the Council are broad, the conditions for their application are strongly restrictive, requiring that they be issued in response to threats to security and receive, at the very least, the acquiescence of all veto-wielding permanent members. In the absence of UNSC decisions, governments often take it into their own hands to enact restrictions on international transactions to induce a change of conduct from other international actors. Unlike sanctions approved by the UNSC, such “unilateral coercive measures” are, according to the UN and many legal experts, contrary to international law and violate the UN Charter.12

In the United States, Congress has partially delegated to the president its constitutional authority to regulate commerce with foreign nations in case of a national emergency, allowing the White House “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States.”13 The president declares national emergencies through the issuance of executive orders that delegate to the Treasury Department the determination of what actors to sanction. The Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) regularly publishes decisions on additions and removals from its lists of persons and entities known as Specially Designated Nationals (SDNs). The inclusion of a person or entity on the SDN list implies the immediate blocking or freezing of all their assets under US jurisdiction and makes it illegal for a US person to conduct any type of economic transaction with them.

Figure 1 plots the evolution of the number of countries subject to trade sanctions imposed by the United Nations, the United States, or the European Union (EU). The figure is based on the Global Sanctions Database (GSDB), the most comprehensive data set on sanctions available to date.14 According to this series, 54 countries — 27 percent of all countries — are currently subject to sanctions. By contrast, in the 1960s the number of sanctioned countries averaged around five, or only 4 percent of countries in existence at the time. In other words, one out of four countries today is subject to sanctions, as opposed to one in fifty six decades ago. Figure 2 considers the share of world GDP in countries under trade sanctions. Here we find slightly greater percentages, with 29 percent of the world economy currently impacted by trade sanctions — as opposed to around 4 percent in the early 1960s.

Figures 1 and 2 are based on data on the number of countries targeted in sanctions regimes imposed by other governments or international organizations. Yet sanctions are now increasingly leveled at persons, entities, or groups rather than at countries as a whole. For example, as we discuss in section 5.2 in greater detail, neither the United Nations nor the United States have sanctioned the government of Afghanistan; rather, they have issued sanctions on the Taliban, the religious and political movement that holds de facto control of state institutions. Even in cases where there are explicit sanctions on governments — such as Iran, Russia, or Venezuela — these are implemented through the designation of specific persons or entities associated with those governments. There are also cases like Mexico, where the US has imposed sanctions on persons for specific reasons, such as alleged links to drug trafficking, without there being any open hostility between the governments of the two nations.

Figure 3 traces the number of changes to the SDN list carried out by the US government since 2009. The data show a clear upward trend. During the first Obama administration, there was an average of 544 new designations per year; in the Trump administration, there were 975 designations per year, a 79 percent increase. These totals have continued increasing during the Biden administration, largely as a result of sanctions on Russia due to its invasion of Ukraine, rising to an average of 1,151 designations per year (18 percent higher than under Trump).15 If we instead focus on net designations (listings minus delistings) we find a similar rising trend, with the number of net designations per year nearly doubling between the first Obama and the Biden administrations.

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Biden administration imposed a similar number of sanctions per year (821) compared with the last two years of the Trump administration (781 per year). Both numbers are substantially higher than any year before Trump reached office. Apart from Russia, Biden’s sanctions primarily targeted entities related to Belarus, Myanmar, and China.16 Meanwhile, Biden removed as many persons from the SDN list as were added in 2021, in part because of his decision to collaborate in implementation of Colombia’s 2016 peace accords and to revoke Trump’s designation of personnel of the International Criminal Court.17

In October 2021, the Biden administration released the results of a review of US financial and economic sanctions. The seven-page document contains little analytical material and largely consists of a restatement of the aims of sanctions, together with some broad recommendations on how to modernize the sanctions regime. The recommendations refer primarily to ways to enhance sanctions’ effectiveness by more clearly linking them with objectives, seeking multilateral cooperation, and strengthening the sanctions-enforcement infrastructure.18

One of the five recommendations in the review refers to calibrating sanctions “to mitigate unintended economic, political and humanitarian impacts,” including those suffered by “non-targeted populations abroad” (emphasis added). The language implies that sanctions, under some conditions, can be intended to have a humanitarian impact and that some populations could be targeted to suffer that impact. The report recommends that Treasury expand sanctions exceptions to support legitimate humanitarian activity “where possible and appropriate.”

Despite the increasing focus on blocking individual and firm-level transactions and the proliferation of humanitarian exceptions (so-called “smart” sanctions), critics highlight their effects on target economies and on the living conditions of vulnerable groups. In 2014, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution stating it was “deeply disturbed by the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures,” and “alarmed by the disproportionate and indiscriminate human costs of unilateral sanctions and their negative effects on the civilian population.”19 The council appointed a special rapporteur tasked with gathering all relevant information and producing studies on the effects of sanctions on human rights. The special rapporteur’s office has concluded that unilateral sanctions lacking UNSC authorization are illegal under international law20 and found that sanctions on Syria, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe, among other cases, limit the enjoyment of fundamental human rights.21

It appears clear that some of the economic and humanitarian impacts of sanctions on target populations is intended. For example, a statement issued by the UK government after freezing Russian central bank assets in February 2022 stated unambiguously that “sanctions will devastate Russia’s economy.” US president Joe Biden boasted on Twitter in March 2022 that “as a result of our unprecedented sanctions, the ruble was almost immediately reduced to rubble” and predicted that the size of Russia’s economy would be cut in half.22 In February 2019, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated, “Things are much worse for the Iranian people, and we are convinced that will lead the Iranian people to rise up and change the behavior of the regime.”23 Pompeo made similar statements about US sanctions in Venezuela the following month.24 Then National Security Advisor John Bolton projected the lost export proceeds to Venezuela as a result of US sanctions imposed in January 2019 to be $11 billion per year.25

From another perspective, the chair of the US House Rules Committee, Congressman Jim McGovern, wrote to President Biden in May 2021, asking him to “lift all secondary and sectoral sanctions imposed on Venezuela by the Trump Administration.”26 In the letter he noted:

…the impact of sectoral and secondary sanctions is indiscriminate, and purposely so. Although US officials regularly say that the sanctions target the government and not the people, the whole point of the “maximum pressure” campaign is to increase the economic cost to Venezuela. … Economic pain is the means by which the sanctions are supposed to work. But it is not Venezuelan officials who suffer the costs. It is the Venezuelan people. Credible sources have consistently found that sanctions have worsened the humanitarian crisis in the country.

The first attempt at quantifying the effect of sanctions on economic conditions in target economies appears to be that of Hufbauer, et al.27 Rather than providing regression-based estimates, the authors present a simple calibration exercise to numerically approximate the economic effects of sanctions. To do so, they rely on direct estimates of market losses due to sanctions constructed from their detailed country studies of 204 sanctions events. For example, they approximate market access losses by the value of exports from the target to the sender country prior to the adoption of sanctions. These market loss estimates are then multiplied by ad hoc “sanctions multipliers” to attempt to estimate lost consumer or producers’ surplus. The multipliers, which range from 0.50 to 5.0, are intended to reflect assumptions on the export supply and import demand elasticities in various settings; the authors recognize that “as a general proposition, we have tried to err on the side of overestimating the ‘sanctions multiplier.’”28 They conclude that comprehensive sanctions regimes (i.e., those that include both trade and financial sanctions) result in a cost to the target equal on average to 4.2 percent of GDP (2.9 percent if Iraq is excluded).29

An attempt to get at these issues comes from Neuenkirch and Neumeier,30 who use a cross-country panel regression framework to assess the effects of sanctions on economic growth. Their data set covers 160 countries during the 1976–2012 period, of which 67 experienced economic sanctions. The authors combine the datasets by Hufbauer et al. (2007) and Wood (2008) for UN and US sanctions, assessing the effect of these as separate interventions. They treat annual GDP growth as the dependent variable and use a set of controls that are for the most part standard from the empirical growth literature. They find a strong, statistically negative effect of multilateral UN sanctions on growth, with the imposition of sanctions associated with a 2.0 percentage point reduction in growth; the effect of US sanctions is statistically weaker and numerically smaller, at 0.9 percentage points. They also find that the effect of sanctions diminishes over time, yet persists for as long as 10 years. The cumulative effect of the imposition of UN sanctions is an average decline in per capita GDP of 26 percent, while that of US sanctions is 13 percent.

Neuenkirch and Neuemier address potential biases from endogeneity or omitted variables through various mechanisms. These include using lagged explanatory variables on the right-hand side of the regression, reducing the sample by excluding countries that are never sanctioned, and restricting the pre-sanctions window of time. They also show that pre-sanctions growth rates are not systematically lower in periods of up to five years immediately preceding the sanctions, contrary to what one would expect if sanctions targeted countries with weaker growth. They further propose an alternative way of constructing a counterfactual that tells us how target economies could have performed in the absence of sanctions by comparing sanctioned economies with those that were “nearly” sanctioned. The latter is a group of countries for which the UNSC l considered sanctions, yet failed to impose them when a permanent member of the council vetoed the resolution. Comparing only sanctioned countries with countries for which sanctions were vetoed, the authors continue to find a strongly negative coefficient on sanctions. Furthermore, they find that countries that benefited from vetoes did not experience slower growth in the years immediately following the vetoes.

More recently, Gutmann, Neuenrkirch, and Neumeier31 use an event-study approach as well as panel difference-in-difference regressions to estimate the effect of sanctions on economic growth and its components. In order to address causality concerns, they rely on comparing sanctioned countries with those only threatened with sanctions. They find that sanctions have a negative effect on GDP growth and its components (consumption, investment, and government expenditures), as well as on trade and foreign direct investment. A sanctions episode leads to a drop in per capita GDP of 2.8 percent during the first two years after sanctions are imposed, with no evidence of recovery even three years after sanctions have been lifted. The detrimental effect is mainly driven by US unilateral sanctions and by financial sanctions, and the authors find that in response to sanctions, democracies shift expenditures toward the military.

Splinter and Klomp32 also evaluate the growth effects of international sanctions, but rather than try to identify a linear effect on the growth rate, they focus on the possibility that sanctions trigger turning points in growth episodes. Concretely, they study whether sanctions generate collapses in economic activity, which they define as growth decelerations where average annual growth falls by 2.0 percent or more for at least four years and in which there is a decline in absolute per capita GDP. They use a linear probability model and find that the likelihood of experiencing a growth collapse rises by 9 percent in the first three years after sanctions are imposed. Interestingly, they don’t find a sanctions effect for longer windows, suggesting that economies adapt to sanctions over time. The effect is only borderline significant at 10 percent; it becomes stronger when they use only sanctions threats, suggesting that credible threats of sanctions may lead economic actors to anticipate the effects of their imposition. Splinter and Klomp address the endogeneity issue by using instrumental variables in their baseline estimation, choosing as instruments a measure of the violation of human rights taken from Freedom House and a measure of the diplomatic clout of a country commonly used in the international relations literature.33

Other papers have looked more directly at the effects on well-being that go beyond aggregate economic conditions. One important question is which groups within a society bear the cost of sanctions. Neuenkirch and Neumeier consider the effect of US economic sanctions on poverty.34 Their dependent variable is the poverty gap — the amount of income that would be necessary to bring all individuals living in poverty to the poverty line — measured at the international poverty line of USD 1.25 a day, adjusted for differences in purchasing power parity. Their empirical approach is based on matching methods, which construct a counterfactual control group by matching countries subject to sanctions with a set of countries as similar as possible to them in a set of pre-sanctions characteristics. Matching is implemented through a procedure known as entropy balancing, which constructs an artificial treatment group as a linear combination of non-sanctioned countries where the weights are calculated to approximate as closely as possible the pre-sanctions characteristic of the sanctioned economies.

The authors find that the poverty gap is 3.8 percentage points of GDP higher when a country is sanctioned by the United States. The adverse effect of US sanctions grows to 7.9 percentage points in the case of the most severe sanctions and is reinforced when US sanctions receive multilateral support. The poverty effect of sanctions grows over time, so that after 21 years an economy that is sanctioned would experience a rise in its poverty gap of 14 percentage points. They also find evidence that before they are sanctioned, target economies tend to be more open to trade, international investment, and foreign aid than other economies, yet experience significant drops in all these indicators, suggesting that at least some of the adverse effects on poverty come from the ability of sanctions to reduce the target country’s role in the global economy.

Gutmann, Neuenkirch, and Neumeier use a similar matching approach to assess the effect of economic sanctions on life expectancy and its gender gap.35 In their baseline estimates, they find that UN sanctions are associated with a decrease in life expectancy of 1.2 years for men and 1.4 years for women, while US sanctions are associated with a smaller decline of 0.4 years for men and 0.5 years for women. In both cases, not only are the coefficient estimates significant but so are the differences between genders. Among the authors’ robustness checks is testing for the effect of sanctions threats that are not carried out. They argue that, in principle, countries that are threatened with sanctions, but where sanctions are not ultimately imposed, should be similar in terms of sanctions determinants to countries where the threat is ultimately carried out. They find that, in contrast to cases in which sanctions are actually imposed, life expectancy does not deteriorate in countries that are merely threatened with sanctions.

Other papers consider the evidence of sanctions’ effects of on children’s health. Kim uses the Threat and Imposition of Sanctions (TIES) data set to assess the effect of sanctions on children’s HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths.36 Using lagged explanatory variables to address issues of endogeneity, he finds that a sanctions episode leads to an increase in the HIV infection rate of children of 2.5 percent and an increase in AIDS-related deaths of 1 percent.

Petrescu uses individual-level micro data from 68 demographic and health surveys to assess the effect of sanctions on infant weight, child health, and mortality.37 Her database covers 228,000 children under age three and includes information on both live and dead children. She estimates a panel regression with country, year, and cohort fixed effects to measure the effect of in utero exposure to sanctions on the weight, height, and probability of death of children. She estimates that being exposed to sanctions during the entire duration of a pregnancy leads to a decrease of 0.07 standard deviations in a child’s weight. The effect of being exposed to nine months of sanctions is approximately one-sixth of being exposed to war, one-third that of having no electricity, and two-thirds that of not having access to medical care.

Afersorgbor and Mahadevan consider the effect of sanctions on income inequality using a panel of 68 target states from 1960 to 2008.38 Using the Hufbauer et al. measures39as their sanctions indicators, they find that a sanctions episode increases the Gini coefficient by 1.7 points, while each additional year of sanctions adds 0.3 points to the Gini. They also show that sanctions lead to significant decreases in the income shares of the four lowest quintiles and an increase in that of the highest quintile. They address endogeneity issues by using lagged covariates as regressors, lagged values of possible endogenous variables as instruments, and restricting estimates to three years around the treatment windows.

Choi and Luo argue that by intensifying pressure on the poor, economic sanctions lead to increases in incidents of international terrorism in the target country.40 International terrorism incidents are those in which the origin of the victims, targets, or perpetrators can be traced back to at least two different countries and are typically aimed at foreign nationals. Choi and Luo use several panel specifications, including pooled and fixed effects negative binomial regressions, and find a consistent effect of sanctions on terrorism, with the imposition of sanctions leading to a 93 percent increase in incidents of international terrorism. They also argue that one of the channels through which sanctions drive terrorism is by raising inequality, and estimate systems of simultaneous equations in which sanctions lead to increases in inequality and higher inequality leads to increases in terrorism. Choi and Luo estimate instrumental variables regressions to address concerns with reverse causation. Although they use three instruments — trade, economic growth, and lagged sanctions — only the last of these is significant, suggesting that any identification comes from assuming away any correlation between lagged sanctions and unobserved determinants of terrorism.

Peksen considers the effect of sanctions on public health.41 His key dependent variable is the mortality rate of children under 5 years of age, with data drawn from UNICEF and the World Health Organization. He estimates a series of cross-country panel regressions for the 1970–2000 period, using both an autoregressive AR (1) specification and a lagged dependent variable to account for different types of serial dependence in the error terms. The author finds no evidence of an effect of a dichotomous sanction variable, but does find an effect of a continuous variable measuring the economic cost of sanctions, as well as a specific effect of sanctions imposed by the United States. A one-standard deviation increase in the cost of sanctions leads to a 4 percent increase in mortality, while imposition of US sanctions leads to a 35 percent increase in mortality.

Remarkably, US sanctions lead to four times as many deaths as a civil war. Being one of the earliest contributions in the literature, Peksen does little to address causality issues and uses a pooled ordinary least squares specification that is problematic if there are country-specific unobserved effects correlated with the error term.

Allen and Letktzian also assess the effect of sanctions on public health.42 Using a cross-country panel data set covering the years between 1990 and 2007, the authors employ a random effects population-averaged generalized estimating equations model (GEE) and a Heckman selection model to estimate the effect of sanctions on government health expenditure, total food supply, immunization rates, life expectancy, and health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE). They find that sanctions negatively impact immunization rates and government health expenditures and that major sanctions — those imposing costs greater than 4 percent of GDP — negatively impact HALE, but find no effect on life expectancy or food supply. The authors argue that while sanctions are less likely to result in deaths than military conflict, they can have a similar effect on impeding individuals from living healthy lives.

More recently, Ha and Nam studied the effect of sanctions on life expectancy in the target country.43 The researchers estimated a cross-country fixed effects panel regression in a data set covering the 1995–2018 period; they also used propensity score matching to address endogeneity concerns. Their baseline estimate finds that a sanctions episode leads to a decline in average life expectancy of 0.3 years. They argue that this effect is mediated by financial development and institutional quality, with countries with more developed financial markets and institutions proving more capable of attenuating these effects.

Clearly, most economic sanctions attempt to affect target economies by creating obstacles to international trade. Often, sanctions directly target trade by enacting import or export bans; other types of sanctions, such as financial sanctions, impair a country’s capacity to participate in the international payments system and thus constrain its international exchange of goods and services. Dai et al. use the Global Sanctions Database44 to assess the magnitude and timing of the effect of sanctions on international trade.45 They use bilateral gravity equations, which model the trade between country pairs as a function of the characteristics of each country and of the relationship between the countries, to estimate how sanctions impact trade between two countries. Each equation controls for country-time effects for both countries, country-pair fixed effects, leads and lags of trade sanctions effects, non-trade sanctions, and membership in international trade agreements.

Dai et al. find that complete trade sanctions — those that apply to imports and exports as a whole — have a significantly negative effect on trade.46 In their baseline estimate, the imposition of sanctions leads to a 77 percent decline in bilateral trade. They also find that declines in trade tend to precede the imposition of sanctions by up to 10 years, and that trade reverts slowly to pre-sanctions levels over a seven-to-eight-year period. Controlling for these effects, however, increases the point estimate of the contemporaneous effect of trade on sanctions to 82 percent. They explain the lead declines as potentially reflecting increasing frictions between countries prior to the sanctions, as well as anticipation of the imposition of sanctions by economic actors, and the lags as reflecting the gradual adaptation of economies to sanctions and weaker enforcement over time. The negative effect of sanctions on trade in the sample is mostly driven by sanctions episodes lasting more than five years.

Wen et al. study the effect of different types of sanctions on the target country’s energy security, using a cross-country database covering the years 1996–2014.47 The main indicator of energy security is energy imports as a percentage of energy use. Estimation of the baseline model is done through a static panel data model with country and year fixed effects, with an additional dynamic specification controlling for lagged dependent variables. They find that unilateral and economic sanctions, as well as US-imposed sanctions,48 lead the target country’s energy imports to rise, but fail to find that effect for EU, UN, and noneconomic sanctions. They also find that sanctions’ adverse effect on energy security rises with the sanctions’ intensity. One possible explanation of these results is that they reflect the greater likelihood that the US will make use of economic sanctions, as compared to the EU or UN.

Wood examines the hypothesis that sanctions could lead to an increase in government repression and adversely affect human rights, on a panel of 157 countries for the years 1976–2001.49 He uses a measure of physical repression that includes abuses such as torture, extrajudicial killings, forced disappearances, and political imprisonment drawn from the Political Terror Scale Project.50 His baseline specification uses ordered probit regressions to assess the effect of sanctions on repression, finding that sanctions are positively associated with repression, that multilateral UN sanctions have a stronger effect than US sanctions, and that repression increases the more severe the sanctions regimes become. The most severe UN sanctions lead to an increase in the probability of repression from 5 to 25 percent; for US sanctions the increase is 16 percent. He also finds some evidence that increases in repression in response to sanctions are less likely to occur in democratic countries. He recognizes that a causal interpretation of these regressions is problematic and offers a system of equations estimated through Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR), where an equation linking sanctions and repression is complemented with three additional regressions in which political dissent, economic conditions, and sanctions, respectively, are the dependent variables.

Similarly, Peksen examines the effect of sanctions on the physical integrity rights of citizens.51 He uses cross-country panel data covering the period between 1981 and 2000 to run fixed-effect regressions using four measures of the physical integrity of citizens: extrajudicial killings, forced disappearances, political imprisonment, and torture. Peksen found that sanctions lead to increases in all of these measures as well as composite indices, a result that is by and large robust across several specifications. In more recent work, Lucena and Apolinário investigate the effect of targeted sanctions on human rights violations in a panel data set of African countries.52 They find that the effect of targeted sanctions is not statistically different from conventional sanctions, and estimate that the protection against loss of life and torture is 1.74 times as likely to worsen under targeted sanctions compared to no sanctions.

Peksen and Cooper Drury look more broadly at how economic sanctions reduce democratic freedoms.53 They argue that leaders facing economic sanctions can manipulate the hardship caused by these measures as a strategic tool to enhance their political support, while the introduction of external threats to the leadership’s political survival creates incentives for the targeted regime to restrict democratic freedoms to undermine any challenge to its authority. Consistent with these predictions, Peksen and Drury find a significant negative effect of sanctions on democracy, with the model predicting a 7 percent reduction in the average Freedom House democracy score the year after sanctions are imposed, an effect that rises to 16 percent in the case of extensive sanctions. The authors also estimate an additional model that tries to quantify longer-term effects, with extensive sanctions being associated with a more than 50 percent decline in democracy scores if sustained over a 15-year period. This is a huge effect, which indicates that sustained sanctions, applied to a country like Argentina over a 15-year period, would lead democratic rights to decline to the level of those in Azerbaijan. Peksen and Cooper Drury also rely on the use of lagged explanatory variables to address endogeneity concerns. Their baseline specifications are either in first-differences or include a lagged dependent variable. Among their robustness tests are specifications in which the explanatory variable is lagged up to four years, and instrumental variables (IV) estimations. They also separate sanctions not imposed with an objective of regime reform that have as strong an adverse effect on democracy as those that aim at restoring democratic freedoms.

In more recent work, Gutmann, Neuenkirch, Neumeier, and Steinbach evaluate the effect of US sanctions on human rights.54 Their approach is to adopt an endogenous treatment specification to distinguish the effect on outcome indicators when countries selected to be sanctioned are systematically different from those that are not. As instruments, they use physical distance from the United States, a measure of genetic similarities between the population of the US and that of the sanctioned country, and a measure of proximity of the target country’s positions to those of the US in the UN General Assembly. This paper is the only case among the cross-country studies that finds ambiguous significant effects, with US sanctions associated with a deterioration of political rights but an improvement in women’s emancipatory rights. Interestingly, it is sanctions not aimed at responding to human rights violations that are positively associated with women’s rights, while both human rights- and non-human rights-motivated sanctions are associated with deteriorations in political rights.

The results of these studies are summarized in Appendix 1. Appendix 2 summarizes the results of country-level studies that use statistical methods to assess sanctions’ effect on human and economic development, some of which is discussed in more detail in section 4. Of the 32 papers surveyed, 30 find significant negative long-run effects on indicators of human and economic development, and one55 finds ambiguous effects, depending on the indicator used. There is only one paper56 that contends that sanctions have a positive effect on living standards. We take a closer look at this study in section 5.3, where we find that its results are based on the use of an inadequate econometric specification and on coding errors.

Together, these studies constitute an impressive array of evidence on the negative effects of economic and even targeted sanctions on living conditions in target countries. Virtually all the studies based on cross-national data identified in our literature search find negative effects from sanctions on their main variables of interest, ranging from economic growth to poverty and inequality, health conditions, or human rights.57 We have found no instances of work using cross-national data that finds consistent positive effects from sanctions on living conditions in target countries, and only a handful that find some ambiguous or nonsignificant results.

Nevertheless, there is clearly room for more research to identify the causal mechanisms at work. The publications surveyed were mostly written over a period during which standards on what are considered satisfactory ways to address causality issues have varied enormously. The use of lagged explanatory variables and the estimation of reasonable systems of equations, which were deemed acceptable ways to address endogeneity concerns a decade and a half ago, are rarely considered satisfactory nowadays. There have also been significant advances in the measurement of sanctions, yet almost all the papers we discussed in this section rely partly or completely on older databases such as that of Hufbauer et al.58 Furthermore, as discussed in section 2, the use of sanctions has evolved toward targeting individuals and entities within countries, suggesting that even results that were valid for coarser measures used in the past may not work in the same way under more recent instruments.

In this section, we focus on three recent cases of economies subject to international sanctions barring or significantly impeding economic transactions: Iran, Afghanistan, and Venezuela. The purpose of these case studies is to provide a clearer understanding of the mechanisms through which sanctions affect living conditions in target economies and how these have evolved in the recent past. For this reason, we focus on three cases where sanctions are still in force, allowing us to observe how recent developments not adequately captured by the cross-national data — such as the shift to personal sanctions, or the proliferation of humanitarian exceptions — have affected vulnerable groups in target economies.

While all three countries are under sanctions regimes today, they are substantively different in many respects. They range from an economy that has been under sanctions for more than four decades (Iran) to one in which economic sanctions were first imposed just five years ago (Venezuela). The purported aims of the sanctions are quite different, ranging from nuclear nonproliferation (Iran), to combating international terrorism (Afghanistan), to restoring democracy (Venezuela). Iran and Venezuela are both oil exporters, but Afghanistan’s economy is primarily dependent on agricultural exports. The three cases also illustrate variations in the instruments of statecraft used to affect target economies: in Afghanistan and Venezuela — but not in Iran — a key obstacle to economic transactions involving the state comes from the lack of international recognition of governments that hold de facto control over their territory.

The modern history of western economic sanctions against Iran goes back to 1952, when Great Britain froze Iranian assets and imposed an oil embargo in response to the Mossadeq government’s nationalization of the country’s oil industry.59 The sanctions were lifted after a coup, partly engineered by the US, led to Mossadeq’s overthrow and fostered a new government under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlevi that entered into profit-sharing agreements with western oil companies.60 In 1979, the Islamic Revolution led to the overthrow of the western-backed government and to Iran’s retaking control of its oil industry’s operations and profits.

US sanctions on Iran followed the Islamic Revolution, and were issued in response to the November 1979 takeover of the US Embassy in Tehran by students who were supported by the new Iranian government. The Carter administration banned oil imports from Iran and froze Iranian government assets that month and banned US exports to Iran and prohibited financial transactions the following year.61

In what has since become a standard procedure for imposing sanctions, the November 1979 asset freeze was implemented through the issuance of an executive order finding that the situation in Iran constituted an “unusual and extraordinary threat” to the national security of the United States and declaring a national emergency to deal with that threat. That allowed the White House to invoke the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and block assets of actors associated with that threat.62 To date, the November 1979 Executive Order remains the longest-standing declaration of a US national emergency.

The asset freeze blocked USD 12 billion in assets — an amount equal to 13 percent of the GDP and 70 percent of the international reserves of Iran at the time. Since the US was by far Iran’s largest trading partner before the revolution, accounting for approximately one-fifth of the country’s total trade, the trade embargo caused significant losses.63 US -Iran trade collapsed immediately after the sanctions and never recovered to its previous levels, even in periods when sanctions were eased (Figure 4).

It is of course hard to isolate the effect of sanctions from the decisions of the revolutionary government to reshape its relationship with the United States. US companies owned 40 percent of Iran’s Oil Consortium (the United Kingdom held 40 percent, with Shell and Total holding the remaining 20 percent). The foreign-owned consortium received half of the profits from Iranian oil production.64 The revolutionary government immediately ended that arrangement, a de facto expropriation of the assets of the Western oil companies.65 Large US oil companies, with the support of the US government, agreed to boycott Iranian oil on world markets at the time. Iran’s oil infrastructure also suffered from the war with Iraq, in which both countries targeted their adversaries’ oil installations.66

The US sanctions were lifted in 1981 as a result of the Algiers Accords.67 Iran agreed to release the hostages in exchange for a US commitment to remove sanctions. The bulk of the frozen funds, however, was not returned to Iran, but rather was used to repay debts and settle claims by Americans against the Iranian government. The US national emergency declaration remained in place, establishing a framework for future sanctions. Trade between Iran and the US plummeted after the revolution; exports to the US recovered only partially after the sanctions were lifted, to around one-sixth of their prerevolution levels, while imports remained at near-zero levels for nearly a decade (Figure 4).

Tensions remained high between Iran and the US even after the Algiers Accords. They took a turn for the worse after the 1983 bombing of Beirut barracks housing US and French soldiers, and groups allegedly backed by the Iranian government were held responsible. In 1984, the US included Iran on the list of state sponsors of terrorism.68 The designation restricted sales of US dual-use items, required the US to oppose multilateral lending to Iran, and withheld US aid to countries or organizations that assisted Iran. At first, the designation had little effect on trade between the countries, as the US continued purchasing Iranian oil, and US exports to Iran had already virtually disappeared after 1980. In response to criticisms that the US was indirectly financing the Iranian regime by permitting oil purchases to continue, Congress passed a law banning Iranian oil imports, and President Reagan ordered a ban on all imports and most exports in 1987.69

US oil companies quickly found a way around the ban and began refining Iranian oil outside the US, sending it to the US as a finished product. Since Iran reflected these sales as trade with the US in its statistics, they explain the recovery in Iran-US exports seen in Figure 4.70 The Clinton administration imposed a total trade and investment ban in 1995 in response to growing concerns about Iran’s nuclear program. This decision effectively closed existing loopholes and brought to an end US trade with Iran.71 In 1996, Congress approved the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act (dubbed ILSA), which imposed penalties on persons investing more than USD 20 million in Iran’s oil sector.72

Much of the international community initially viewed the US actions as unjustified, deriving from the country’s hostile diplomatic relationship with Iran after the 1979 revolution. The sanctions thus had little international traction and had some pushback, and the EU even threatened to file a grievance against ILSA with the World Trade Organization73 and forbade EU persons from complying with US regulations against Iran and Cuba that jeopardized the EU’s trade commitments.74

Key international actors began to change their position as evidence surfaced in 2002 regarding Iran’s construction of two secret research facilities for producing enriched uranium and heavy water.75 During the next three years, repeated International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections led to the progressive disclosure of information on Iran’s nuclear operations. Iran argued that its decision to hide the programs responded to US hostility even against publicly acknowledged activities.76 In August 2005, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad reneged on commitments made by his predecessor and announced that Iran would resume uranium conversion activities. In the following month, the IAEA found that Iran was out of compliance with its obligations under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.77

These findings formed the basis for the first United Nations sanctions, issued through a set of Security Council resolutions approved in 2006.78 The decisions froze the assets of entities and persons involved in the program, prohibited the transfer of nuclear items to Iran, banned Iranian arms exports and investment abroad in uranium mining, and called for restraint and vigilance on financing involving Iran and transactions with Iranian banks, including with the Central Bank. In parallel, the US issued Executive Order 13382, which froze assets belonging to listed persons identified as proliferators of weapons of mass destruction.79