December 25, 2012

On December 31, 2011 the Net International Investment Position (NIIP) of the United States was a little worse than negative 4 trillion dollars. This means that total holdings of U.S. assets such as stocks, bonds (private and government) and real estate, by foreigners exceeded total holdings of foreign assets by people in the United States by more than $4 trillion. This is more than one quarter of the annual GDP of the United States. Despite this negative position, in 2011 American-owned assets had still generated $235 billion—1.6 percent of GDP– more income than was lost in corresponding payments to foreigners.

This unusual set of circumstances is not likely to continue. Earlier this month, the OECD released a report “Looking to 2060: Long-term global growth prospects” based on the baseline projections of its June Economic Outlook. The report projects that real per-capita GDP in the United States will rise 1.58 percent per year from 2010 to 2060. That is, output per person will be 119 percent higher in 2060 than in 2010. On the other hand, the OECD also projects that an increasing amount of that production will represent income to foreigners.

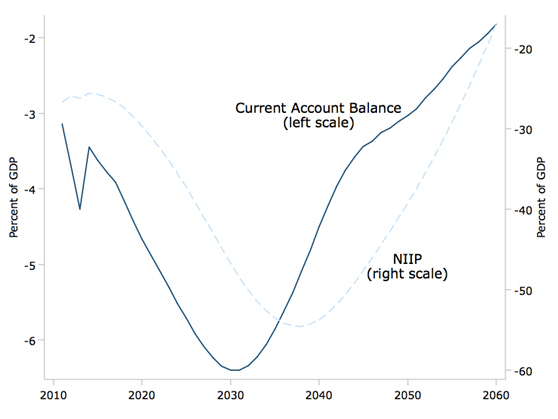

Apart from a brief surplus in 1991, the last 30 years have seen negative U.S. net national savings in the form of the current account deficit—essentially a large trade deficit offset in part by a small net income from assets. The OECD projects that the current account deficit will grow to a record 6.4 percent of output by 2030 (over $1 trillion annually in today’s economy) before steadily recovering over the next three decades as net foreign investment in the United States declines. This projected pattern of current account deficits implies large sales of U.S. assets to foreigner and therefore further deterioration of the U.S. NIIP. By 2038, net foreign ownership of U.S. assets will rise from 26.7 percent of GDP to something closer to 54.5 percent.[1] If these assets generate a return akin to government bonds, then in 2040 this will represent a flow of cash out of the United States equal to about 4 percent of GDP or $640 billion a year in today’s economy.[2]

Source: OECD and author’s calculations.

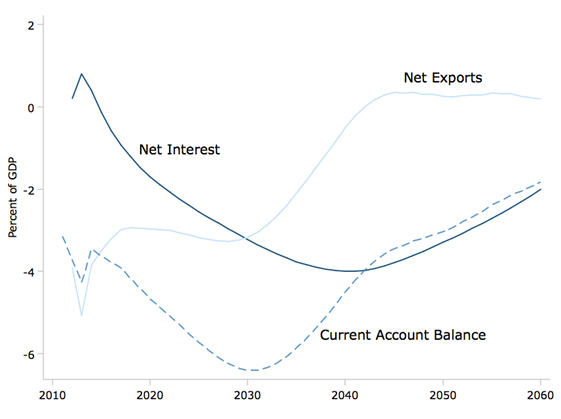

So if net interest payments still continue to increase, why does the current account balance improve? The answer is that between 2030 and 2040, the trade balance must improve. At the same time the United States loses (public and private) net interest income from foreigners, the U.S. is selling relatively more goods in comparison to purchases. The latter means the United States gradually retains what was a flow of money out of the country amounting to 3 percent of GDP. Usually this would be accomplished by a drop in the real value of the dollar, which would make U.S. goods cheaper to the rest of the world and foreign goods more expensive to people living in the United States.

Source: OECD and author’s calculations.

In effect, the OECD’s analysis implies that after growing by more than 100 percent as a share of GDP, the United States NIIP will eventually stabilize as the United States’ trade deficit moves toward balance and eventually a modest surplus.

The OECD’s analysis is interesting for two reasons. First it highlights the long-term implications of large trade deficits. Instead of the United States buying more than what it pays for from abroad, it will eventually be selling more abroad than what it imports. This corresponds to a reduction in living standards of roughly 4 percent compared to a situation where we continue to run trade deficits of the current size.

It is important to recognize that this drop in living standards is due to the trade deficit, not the budget deficit. The reason we have a trade deficit is because the dollar is higher than a level that is consistent with balanced trade. Those who are upset about the prospective drop in living standards due to greater foreign ownership of U.S. assets should be upset first and foremost about the over-valued dollar, not the budget deficit.

The second point is that even with a larger share of output being drained off by foreigners, there is still projected to be a large rise in living standards over this period. Over the full 50 years output per person is projected to increase by 120 percent. Even if an additional 4 percent of output is diverted to foreigners who own U.S. assets, output per person will still have more than doubled over this period.

A third point is that the switch from having a trade deficit to surplus is likely to have a big impact on distribution. While we protect many high-paying occupations from international competition (e.g. doctors, lawyers, etc), we force other workers to compete with the lowest paid workers in the world. When conditions of competition turn again in the U.S. favor, this will improve the situation of manufacturing workers and other workers subject to international competition relative to doctors and lawyers. This gain in relative position, and the implied rise in wages, could easily swamp the negative effects of increased foreign indebtedness.

In other words, most workers will probably be better off when our trade deficit moves toward balance. They would probably be best off if this adjustment happened next week rather than 25 years from now.

[1] This assumes inflation in the United States runs two percentage points slower than the rest of the world, and foreign assets depreciate correspondingly. According to the OECD data, the average growth in the GDP deflator in the rest of the world– weighted by net savings— approaches about 4 percent per year, compared to 2 percent in the United States.

[2] The net interest on assets would be greater than the implicit interest on net assets because U.S. government bonds are projected to generate a higher rate of interest than foreign government bonds by 2022. Even with a zero net investment position, the interest income would be less than interest outgo.