December 04, 2013

In late October, Uruguayan president José Mujica announced that he planned to withdraw his country’s troops from Haiti, where they make up 11 percent of the U.N. peacekeeping mission. Citing the long delayed legislative elections, Mujica told the press:

One thing is to try to help the Haitian people build a police force that is in charge of security. That’s fine… Another thing is being there indefinitely with a regime that we think is at least dubious in terms of a continuity of democratic renewal.

MINUSTAH, as the U.N. mission is known, has been in Haiti since 2004 following the coup that ousted President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. In October the mission’s mandate was extended by the U.N. Security Council for another year, though a gradual drawdown of troops was also agreed. After his initial statements, Mujica traveled to Brazil where he met with President Dilma Rousseff. Brazil leads MINUSTAH and is the largest troop-contributing country, accounting for 16 percent of the personnel.

After the meeting, Mujica stated that he and Rousseff agreed that the mission should not become a “Praetorian Guard” to protect a government that was not moving forward democratically. On November 20, the U.N. spokesperson for the Secretary General acknowledged that “preliminary and informal discussions have taken place with the Uruguayan representatives in New York regarding the planned withdrawal of a part of their troops,” but that “no formal notification has as yet been exchanged.”

On November 25, before travelling to Haiti for a meeting with President Martelly, Uruguayan Foreign Minister Luis Almagro met in New York with Brazilian and U.N. officials to discuss MINUSTAH’s presence in Haiti. Almagro stated that while Uruguay would only gradually withdraw its troops in line with the Security Council resolution, if “autocratic” tendencies in the Haitian government continued, they would immediately withdraw. Specifically, Almagro conditioned continued Uruguayan support to MINUSTAH on the holding of the overdue legislative elections.

Regional Implications

In June 2012, the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) met to discuss MINUSTAH and agreed to form a working group “for the purposes of elaborating a scheme on the strategy, form, conditions, stages, and timeline of a Plan of Reduction of Contingents of the Military Component of the Mission.” Though there has been little movement since then, the recent actions by Uruguay may change that.

Foreign ministers from Argentina and Brazil met November 21, announcing that they shared a common view on MINUSTAH and that while “it should not be perpetuated” neither could it depart immediately. According to news reports, the ministers believed the withdrawal would require a “regional vision” and should again be brought up by UNASUR in early 2014.

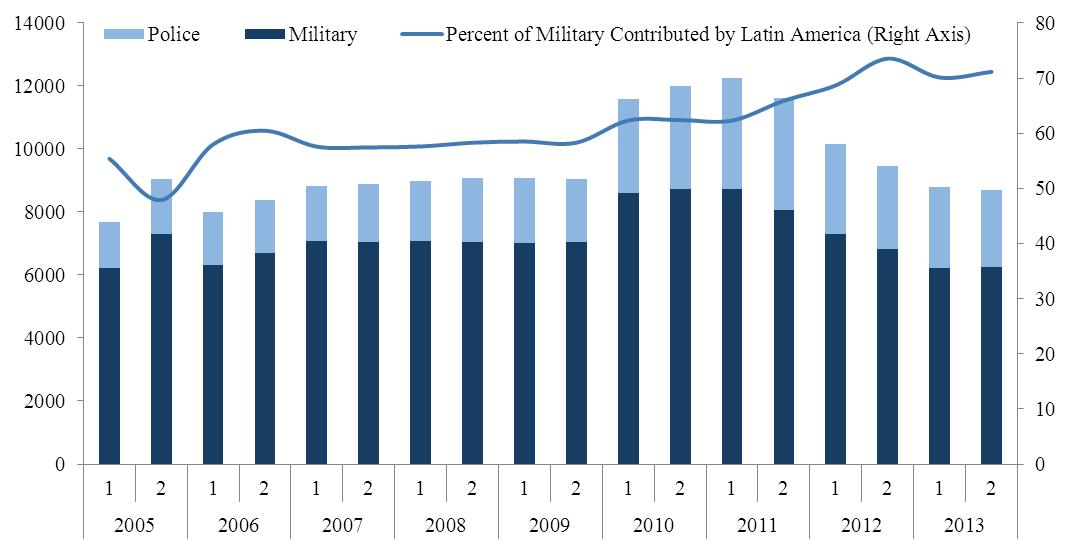

Together, the nine South American troop contributing countries make up about 50 percent of MINUSTAH personnel and nearly 70 percent of the military contingent, meaning any movement for withdrawal from the region will have huge implications. As can be seen in the Figure below, while MINUSTAH has diminished in size over the last two years, most of this has just been the phasing out of the post-earthquake surge in personnel. The current size of MINUSTAH is only 4 percent smaller than pre-earthquake. But while overall levels have been reduced, Latin America’s share of military personnel has steadily grown. MINUSTAH is now more reliant on Latin America than ever.