January 11, 2011

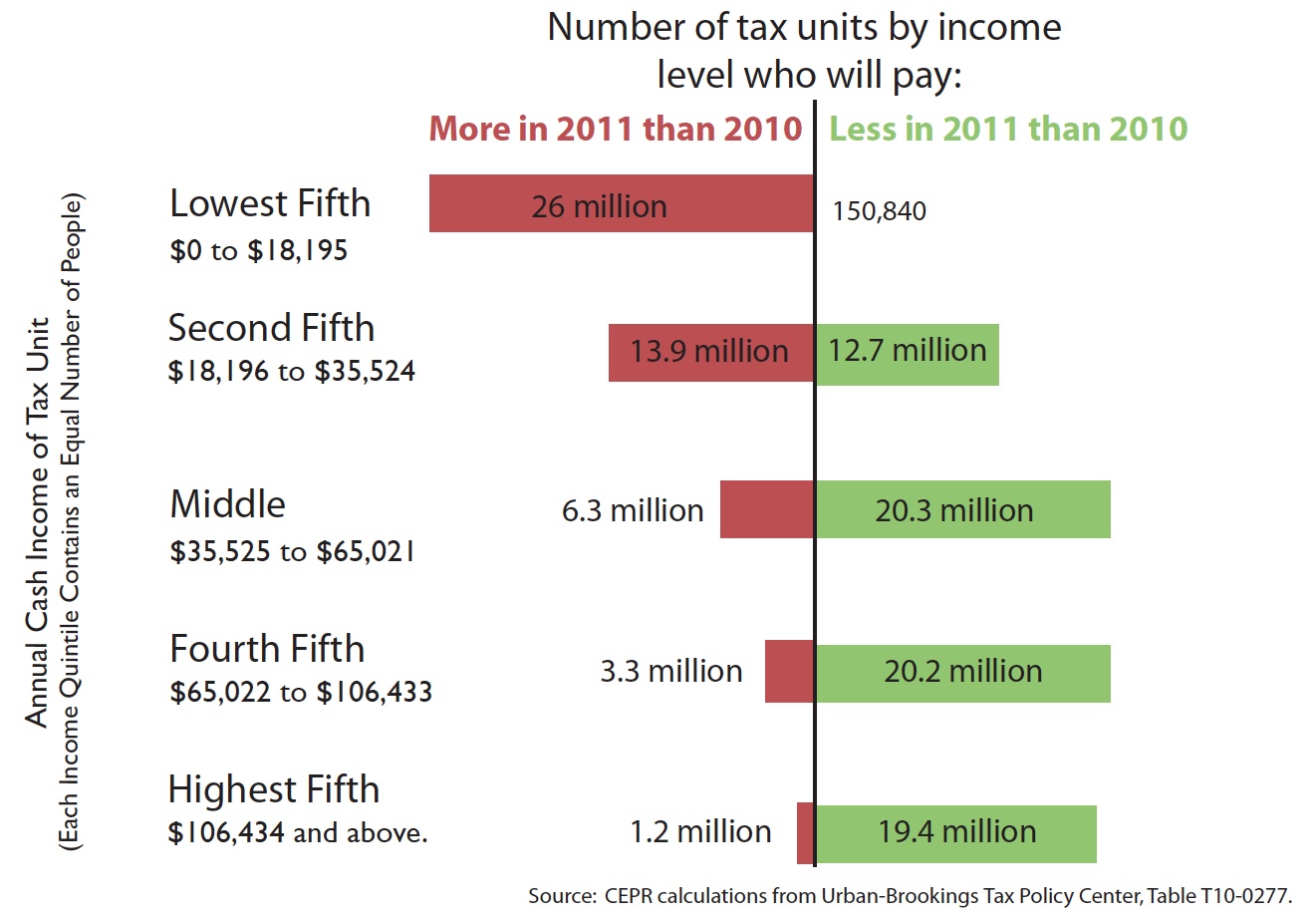

On December 6, the President said “there is no reason that ordinary Americans should see their taxes go up next year.” Apparently, the Administration staff who negotiated the deal found a reason. According to the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, some 51 million taxpayers will see their taxes go up in 2011. The vast majority of them—40 million tax units—are low-wage workers with incomes below $35,000. Low-income workers are the only income group that will lose income this year compared to 2010 under the deal. Other groups, including most middle-income families and nearly all high-income ones, will receive a bigger tax cut in 2011 than in 2010.

Although a few news outlets have reported this fact, it is not widely understood by the public, or even by most advocates and analysts working on policy related to low-income families. This is partly due to the White House’s failure to acknowledge the hike. Instead, when it announced the deal, the White House Press Secretary touted the extension of some tax cuts for low-income families with children and stated that “working families won’t see their tax cuts go away next year.”

Also contributing to the lack of understanding is the failure of some prominent organizations that supported the deal, ones that are looked to by many as having particular expertise in tax policy related to low-income people, to make the cut clear. For example, in his statement endorsing the deal, Bob Greenstein of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, described the tax provisions as “protect[ing] low- and middle-income workers and … boosting their incomes,” “achieving everything [the White House] sought for low- and middle-income families,” and “not compromising on these issues.” (Kudos, on the other hand, go to the Urban Institute’s Roberton Williams and Howard Gleckman, CAP’s Michael Linden and EPI‘s Andrew Fieldhouse for their accurate analysis of deal’s impact on low-wage workers).

The tax hike for most low-income workers is due to the replacement of the Making Work Pay tax credit in 2010 with a 2-percentage-point reduction in the payroll tax rate in 2011. This change could have been designed in a way that avoided an increase for most low-wage workers—consistent with the President’s statement that “there is no reason that ordinary Americans should see their taxes go up next year”—but it was not.

Established in the 2009 Recovery Act, the Making Work Pay tax credit provided tax benefits in 2009 and 2010 to all workers with adjusted gross incomes below $95,000 ($190,000 for joint filers). For the vast majority of low- and middle-income workers the tax credit was equal to $400 (single filers) or $800 (joint filers). For both single filers with incomes below $20,000 and married couples with incomes below $40,000, the payroll tax reduction provides less of a tax reduction than the Making Work Pay credit. For example, a married couple with income of $25,000 will pay $300 more in federal taxes in 2011 under the tax deal than they did in 2010 (assuming the same annual income). Similarly, a single filer with income of $10,000 will pay $200 more in federal taxes in 2011 under the tax deal than they did in 2010.

Although we don’t have any other information on the demographics of who lost as a result of the deal, it is worth noting that a substantial portion of those who lost ground are likely workers with disabilities. Disability researchers Peiyun She and Gina Livermore have documented that almost half (47.4 percent) of working-age adults (ages 25-61) with incomes below the official poverty line have one or more disabilities. Their research suggests that roughly half of low-income people with disabilities work at some point during the year. Another demographic group that is likely to have been disproportionately impacted is young adults, who are more likely to be working in low-wage jobs and have lower annual incomes than middle-aged adults.

When the Administration proposed replacing the Making Work Pay credit with a uniform payroll tax reduction, it would have been obvious to their lead negotiators that most low-income workers would experience a tax hike in 2011 as a result. Especially since, as the Wall Street Journal has reported, one of the President’s lead negotiators, Gene Sperling, had been pushing the payroll tax reduction within the Administration for some time as an alternative to the Making Work Pay credit.

In his 2005 book on economic policy, Sperling argues that progressives should be particularly concerned about “silent trade-offs”—what he describes as well-intentioned policy decisions in which the “potential downsides to other workers are never openly considered and weighed in making the decision.” If Sperling had taken his own advice to heart in this case, the Administration would have openly considered and weighed the trade-off involved in replacing the Making Work Pay Credit with a payroll tax cut. If it had wanted to avoid a tax hike for more than 40 million low-income workers, it had at least four options:

1) sticking to its guns and insisting on a full extension of the Making Work Pay credit; or

2) modifying the payroll tax reduction in a way that would have held low-income workers harmless—for example, by graduating the payroll tax reduction in a progressive way that provided a higher percentage-point reduction to low-income workers; or

3) coupling the payroll tax reduction with a broad-based increase in the EITC, one targeted on roughly the bottom half (in income terms) of tax units eligible for the EITC; or

4) coupling the payroll tax reduction with a less broad-based increase in the EITC, one that increases the EITC for groups—primarily single adults and couples without children—who are currently only eligible for a very small EITC, face the highest federal tax rates among low-wage workers, and who did not receive any increase in the EITC in either the Recovery Act or the Bush tax cuts.

It is somewhat hard to imagine that Republicans would have been willing to walk away from what they were being given—including a full extension of the massive Bush tax cuts for the wealthy and an extraordinary reduction in the estate tax—if the Administration had held its ground by arguing they simply could not agree to a deal that cut the tax credits available to the majority of low-income workers who had been among the hardest hit by the economic downturn.

Looking ahead, the White House could go a long way toward setting things right by proposing an increase in the EITC for low-wage workers without children in its FY2012 budget, something that candidate Barack Obama said he’d do if elected. Currently, these workers are only eligible for the EITC if they have extremely low incomes and are between the ages of 25 and 60. And even when they are eligible, the maximum credit they are eligible for is miniscule.

This can be seen by comparing the EITC for a tax unit without children to the EITC for tax units with one child. For a single filer with one child, the maximum income for the EITC is more than 2.5 times the maximum for a single filer without a child ($36,052 vs. $13,660). For a married couple with one child, the difference is a bit smaller, but still more than double ($41,132 vs. $18,740). The difference between the maximum credits is even larger—the EITC maximum credit for a tax unit with no children is $464 compared to $3,094 for a unit with one child. The EITC is only one of the benefits in the tax code provided to filers with children that is not available to other filers. If these other benefits were taken into account—most importantly, the Child Tax Credit, which provides up to $1,000 per child, and the dependency exemption, which reduces taxable income by a fixed amount ($3,650 in 2010) for each child—the difference would be even larger.

This isn’t to say that low-wage workers with children get “too much”—if you’re trying to support a family on a $9 an hour job, one that typically doesn’t provide health insurance or paid sick leave, you deserve every penny you get and more—but it does illustrate how little the much lauded EITC does to help the majority of low-wage workers who don’t have children. In fact, for low-wage workers without children, the combination of the EITC and a minimum wage job still leaves them worse off than they would have been in 1979 just receiving the minimum wage (if working full-time, they would have earned roughly $2,500 more in 1979 than today). It will take a lot more than an EITC expansion to get these low-wage workers what they deserve, but it’s a start.