October 07, 2012

Greg Ip is usually a solid analyst of economic trends. However he apparently agreed to adopt house standards in his column for the Washington Post that told readers that “Obama is saving the economy, but maybe not in time to save the economy.”

The main assertions in the piece are just flat out wrong. For example, the column tells readers:

“Paradoxically, the same forces that made for such a weak recovery during Obama’s first term suggest that the next four years will be better, regardless of who holds the White House. Right now, businesses, households and governments are all trying to wrestle down their debts. That “deleveraging” saps spending and blunts the power of low interest rates.”

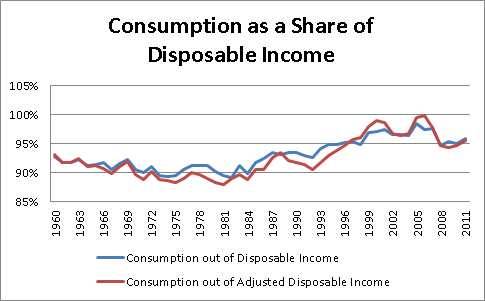

This statement would lead readers to believe that the problem is low consumer spending and low business investment because of high debt burdens. However the Commerce Department’s data strongly disagrees with this assessment. Here is the ratio of consumption to disposable income over the last four decades. (Adjusted disposable income has to do with the statistical discrepancy in GDP accounts.)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The Commerce Department strongly disagrees with Ip, telling us that consumption remains far above its long-term share of disposable income even if it is somewhat below the peaks driven by the wealth from the stock and housing bubbles. It also disputes the business side of Ip’s argument. In the second quarter of 2012 (the most recent quarter for which data are available), businesses spent an amount equal to 7.4 percent of GDP on equipment and software investment. In 2007, the last pre-recession year they spent 7.9 percent. See the collapse? In fact, given the large amounts of excess capacity in major sectors of the economy, business investment is surprisingly high.

The real story of the current shortfall in demand is very simple. The wealth generated by the housing bubble led to unusually high consumption. It also led to a building boom in both residential and non-residential construction. Consumption fell back to more normal levels after the wealth that was driving it disappeared. Construction went from boom to bust, as we had enormous overbuilding of both homes and most types of non-residential structures.

There is no simple way to replace this demand from the private sector. And contrary to what Ip asserts, our best and really only hope is to reverse current patterns of trade. While Ip notes that we have had a surge of exports, what matters for demand is net exports, which is the difference between exports and imports.

There has been very little progress in reducing the country’s trade deficit over the last four years. Most of the gains have been from reduced imports as a result of the recession. The only plausible mechanism for getting the trade deficit down is by reducing the value of the dollar which will make U.S. goods more competitive internationally. President Obama has made little progress on this front, leaving most of the work to the person occupying the White House for the next four years.

Unless trade is closer to balance, the only way to maintain anything close to full employment (absent another bubble) will be to run large budget deficits. That is accounting — there is no possible way around this fact.

Ip also comments that, “home prices, which hit bottom in January, are rising steadily.” That should scare us. Inflation adjusted house prices are already back to their long-term trend level. The last thing that any sane person should want to see is a re-inflation of the bubble. Anyone feel good about another plunge in house prices of 20-30 percent? It won’t be any more fun the next time it happens.

Finally, Ip tells us the:

“financial crisis that bears the fingerprints of every president going back to Lyndon Johnson, who turned mortgage giant Fannie Mae over to private shareholders, as well as Carter, who ushered in the era of deregulated finance by loosening interest-rate controls.”

Actually, we could go further back to the mortgage interest deduction and the creation of Fannie Mae, but the key point is that if anyone had been awake at the White House or the Fed in the years 2002-2006 they would have been able to notice the huge housing bubble that was driving the economy. Bubbles are not built on fundamentals, which mean that they will burst. And it was 100 percent predictable that when this bubble burst that it would take down the economy with it. While prior presidents had certainly made serious mistakes in regulation (give Clinton a gold medal in this category), none of these mistakes put us on an inevitable path to the disaster that we are now facing.

The people in power at the time should not be allowed to pass the buck and evade responsibility. Many of those convicted of crimes grew up in poverty, but we still send them to jail. The case for punishment of the Greenspan-Bush gang would be more solid than for almost any prisoner sitting behind bars today.

Addendum: Note on Deleveraging

There has been considerable discussion by economists and in the media of “deleveraging.” There is some fundamental confusion on this issue. It is important to remember that debt for one person is an asset for another. While it is likely that the debt of underwater homeowners does more to depress their spending than the wealth of the mortgage holders does to increase theirs, it is not really possible to explain much of the downturn by the amount of underwater mortgage debt in the economy, which is estimated at $700 billion to $1.1 trillion.

Furthermore, as this gets paid down (the deleveraging), this is simply a form of saving. Suppose that we snapped our fingers and underwater homeowners suddenly were set right-side up in their mortgages. This would not be hugely different than if they suddenly accumulated $1.1 trillion in housing equity. While it is likely that being underwater does more to depress consumption than being above water by the same amount does to raise it, we are likely talking about relatively small sums. (To believe otherwise, we would have to think that underwater homeowners would increase annual spending by something like $30,000 a year if they were no longer underwater. That would be pretty impressive for a group of homeowners with average income that is probably around $70,000.)

Greg Ip’s Reponse

Greg Ip was good enough to write a substantive response and allowed me to post it:

Greg is absolutely right that consumption and housing have not made the contribution to this recovery as they did in prior recoveries. The question is whether there is any reason that we should have expected them to.

Comments