October 15, 2013

There’s a lot of silliness going around about how the dollar may lose its status as the world’s reserve currency if we default. The ordinarily astute Floyd Norris contributed to this confusion in a column last week implying that we may no longer be able to borrow internationally in dollars if this happened.

In reality, it is unlikely that we do risk being the world’s preeminent currency in any plausible scenario. (This is also Norris’ conclusion.) Furthermore, the immediate result of this loss of status would be positive in any case.

A first point is useful just for clarification. Being a reserve currency is not a zero-one proposition. The dollar is the preeminent reserve currency, which means that most of the world’s reserves (@70 percent, last time I checked) are held in dollars. However other currencies like the euro, the British pound, the Japanese yen, and even the Swiss franc are also held as reserves.

If there was a loss of confidence in the dollar, we are presumably talking about a drop in the ratio of reserves held as dollars. Maybe it would fall to 40 percent, perhaps 30 percent. It is almost impossible it will fall anywhere near zero as long as the United States is in one piece with a functioning economy.

The effect of this loss of confidence would not be to deny the United States the ability to borrow in its own currency. Many countries borrow in their own currency, including countries like Malaysia and Colombia, which are not ordinarily thought of as titans of the world financial system.

Less stable countries typically pay somewhat of risk premium based on the risk of inflation in that country’s currency and the risk of the demise of the country (think Yugoslavia). In several cases this risk premium is negative. For example, the interest rates on Japanese, Swedish, and Danish bonds are all lower than the interest rates on U.S. bonds. These countries do not appear to have suffered from not having the world’s preeminent reserve currency.

There is the second issue of the dollar falling in value relative to the currencies of other countries if the dollar loses its status as the preeminent reserve currency. This possibility should be cause for celebration, not fear. First of all, a lower valued dollar was the ostensible goal of both the Bush and Obama administration when they demanded that China and other countries stop “manipulating” their currency.

In this context, “manipulation” means holding down the value of their currency against the dollar. In other words, it means pushing up the value of the dollar. In spite of it being official policy that we want a lower valued dollar we are now supposed to be terrified that we might get a lower valued dollar. Welcome to economics in Washington.

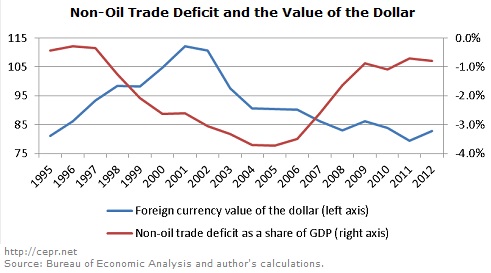

The reason why we would want a lower valued dollar is that it would make U.S. goods more competitive in the world economy. We would cut back our imports and increase our exports. This is hardly a novel theory, this is econ 101. And, in fact the world follows pretty closely on what the textbooks say should happen. The trade deficit exploded in the late 1990s when the value of the dollar soared following the East Asian financial crisis. (This is when developing countries like China first decided that they needed massive amounts of dollar reserves). The trade deficit then shrank in the last decade, with a lag, after the dollar fell in value. The chart shows the non-oil deficit, since we would not expect the demand for oil to be very responsive to the value of the dollar. (The chart does not include the increase in oil exports, since that data was not immediately available when I put the chart together and BEA’s website is now down.)

In short there is every reason to believe that if a loss of confidence in the dollar led to a fall in its value that we would see a decline in the size of the trade deficit. If the trade deficit fell by 2 percentage points of GDP (@ $330 billion), this would directly lead to close to 2.7 million jobs. If we assume a multiplier effect of 1.5, then we would be looking at over 4 million jobs being created by this loss of confidence in the dollar. Are you scared yet?

What is really amazing about how economics reporters discuss this issue is that there is no plausible alternative mechanism for creating anything like this number of jobs at this point in time. Sure we could create jobs through additional government spending. And that is as likely as? (Sorry, this is a family friendly blog.) There are probably not 20 members of Congress, zero in leadership positions, who would get up and argue for a big round of spending to get the economy going again. The whole debate right now is how much we are going to cut.

Where else would the new demand come from? Those who are hoping for a burst of consumption have not been looking at the data. The ratio of consumption to disposable income is actually quite high right now. There is no plausible story as to why we would think consumers get really really optimistic and start spending an even higher share of their income. The only time they spent a higher share than they are now is during the bubble years. And with the bubble wealth gone, there is no reason to think that spending shares will get back to bubble levels.

The same story holds for investment. The investment share of GDP is almost back to its pre-recession level. That is strikingly high given the large amounts of excess capacity in many sectors. In short, the idea that we could see an investment boom any time in the foreseeable future is just silliness.

This means that if we want to see job growth, we should want to see the dollar fall against other currencies. My preferred way of getting there is not a debt default, but if a default does occur and a drop in the dollar is one outcome: remember, that is a good thing.

Comments