March 28, 2014

[Note: this blog post has been updated with the BLS data from March, updated post here]

At the beginning of 2014, thirteen states increased their minimum wage. Of these thirteen states, four passed legislation raising the minimum wage (Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island). In the other nine, the minimum wage automatically increased in line with inflation at the beginning of the year (Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Missouri, Montana, Ohio, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington State).

Earlier this week, Goldman Sachs conducted a simple evaluation of the impact of these minimum-wage increases on state employment levels. Goldman Sachs compared the employment change between December and January in the 13 states where the minimum wage increased with the employment change in the remainder of the states, where the minimum wage remained constant. They concluded that “January’s state-level payrolls data failed to show a negative impact of state-level hikes (in the minimum wage). Relative to recent averages, the group of states that had hikes at the start of 2014 in fact performed better than states without hikes. While this is only one month’s data, it suggests that the negative impact of a higher federal minimum wage–if any–would likely be small relative to normal volatility.”

Today, the BLS released new data on state level employment patterns, now including the month of February. Building on the analysis done by Goldman Sachs, we can integrate the February data and get a better picture of how the states that raised the minimum wage fared relative to those states that did not.

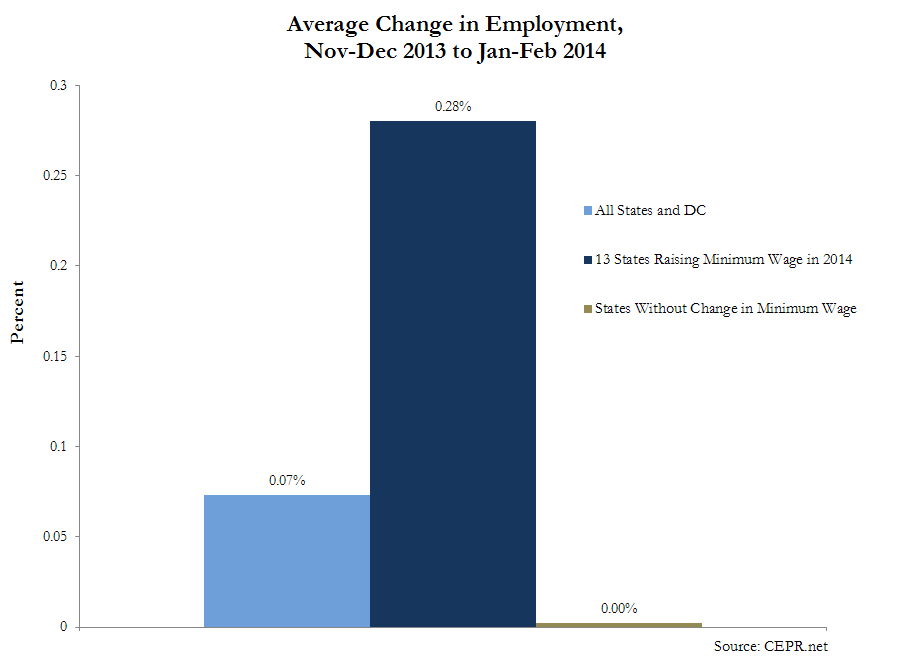

The chart below summarizes the results. The average increase in employment in the thirteen states where the minimum wage rose was 0.28 percent. (This was calculated as the percent growth in average state employment in January and February relative to average employment in November and December). Over the same period, in the states where the minimum wage remained unchanged, employment was essentially zero (up by just 0.002 percent).

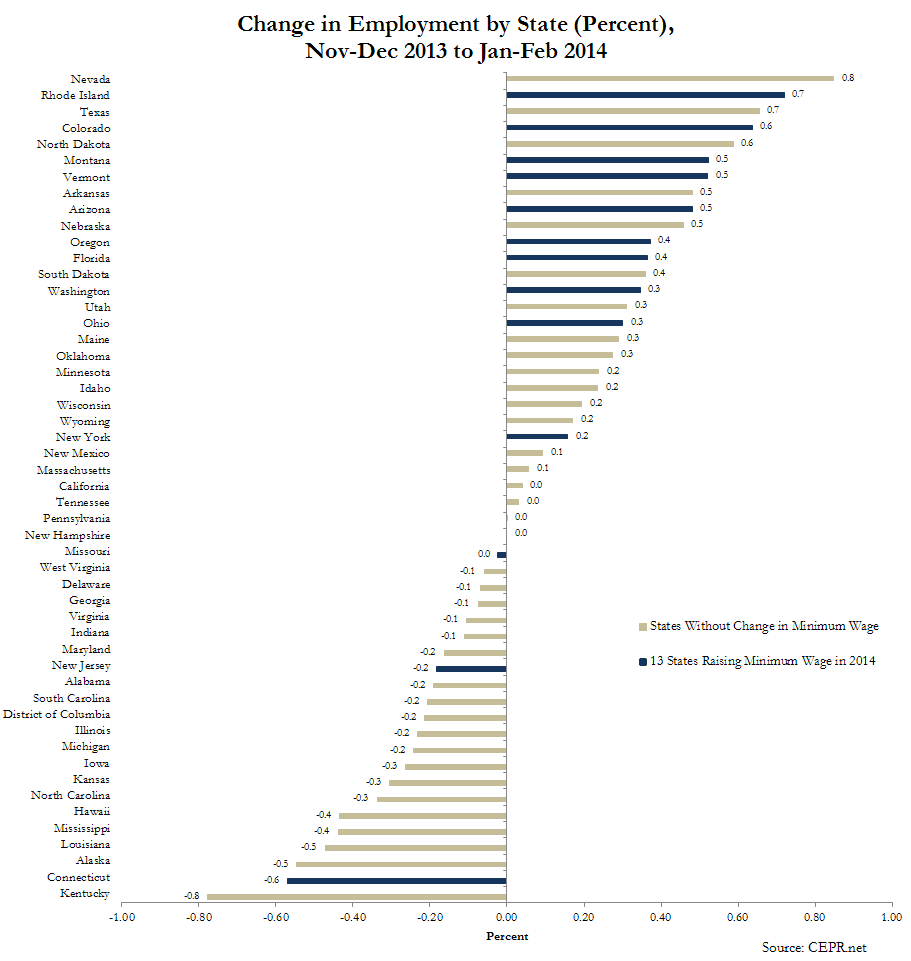

The graphic below lists the corresponding employment change (in percent terms) for each individual state. This chart shows a lot of variation across the states, but the tendency for more rapid employment growth in the thirteen highlighted states is still clear.