February 24, 2017

Neil Irwin has a good piece this morning discussing the evidence on the economy’s growth potential. As he points out, the key question is how much slack remains in the economy. The key issue in this debate is the extent to which we can expect employment to rise.

Most of the debate deals with the extent to which we can expect more people to enter the labor market. The current 4.8 percent unemployment rate is reasonably low by any measure. While it can go somewhat lower, that will not allow for much further expansion of the economy. The bigger question is the extent to which we should expect people who are not in the labor force, meaning they are neither working nor actively looking for work, to come back into the labor force if the job market improved. On this point, there is considerable debate.

The basic story is straightforward, if we focus exclusively on prime-age workers (ages 25–54), the labor force participation rates are close to 2.0 percentage points below pre-recession levels and 4.0 percentage points below 2000 peaks. Those who insist that we are near full employment argue that this is pretty much the best we can do and that these drops are permanent. Those like myself, who think we can do much better, argue that we should be able to return to past rates of labor force participation rates (LFPR) among prime-age workers.

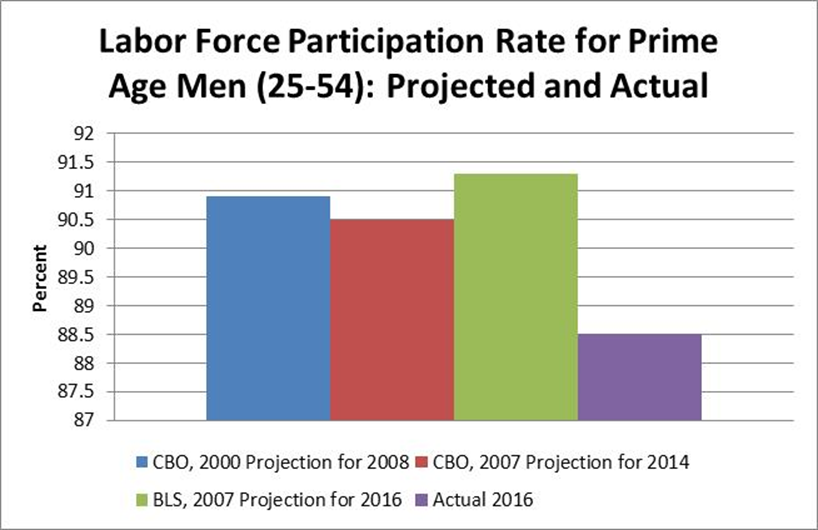

In this respect, I would like to enlist the help of the ghost of forecasters past. The figure below shows projections of prime-age LFPR for men from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Source: CBO and BLS.

The first bar is a projection CBO made in 2000 for 2008. It projected a LFPR for 2008 of 90.9 percent. The second projection is also from CBO. In 2007 it projected a LFPR for prime-age men in 2014 of 90.5 percent. The third bar is a 2007 projection from BLS for 2016. It projected a LFPR for prime-age men of 91.3 percent. This compares to an actual LFPR last year of 88.5 percent, almost three full percentage points lower.

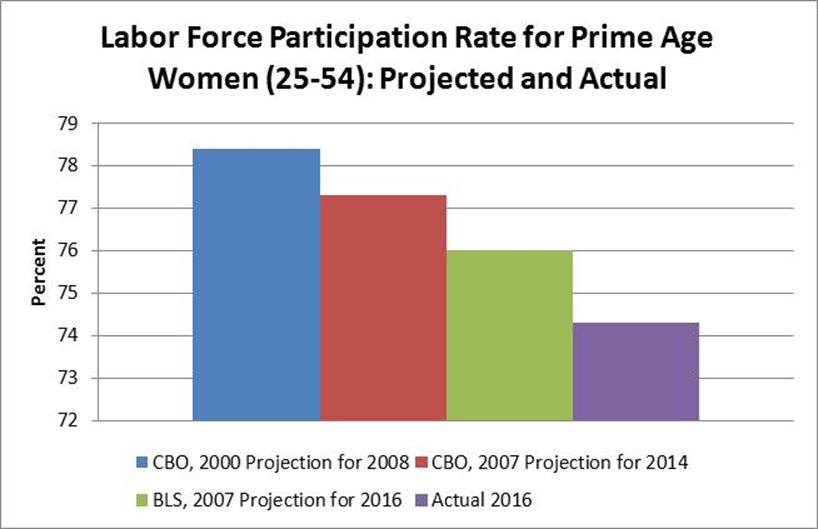

There is a similar gap between recent projections and current reality for women as well. The figure below shows the projections for LFPR for prime age women.

Source: CBO and BLS.

The first bar shows the CBO projection from 2008 for the LFPR for women in 2008. This was 78.4 percent. The second projection is the 2007 CBO projection for 2014. At that time it projected a LFPR of 77.3 percent. This reduction was likely to due to the fact that women’s LFPR dropped in the 2001 recession and did not fully recover in the upturn. The third bar is 2007 projection from BLS for 2016. It projected a 76.0 percent LFPR, which is still 1.7 percentage points above the actual for last year.

These past projections are useful because they were made by economists who were experts in the field. They had knowledge of trends in education and technology. Based on this knowledge, they expected a substantially larger share of the prime-age population to be in the workforce today than is currently the case.

If we take the average of the three projections for men, it comes to 90.9 percent, 2.4 percentage points above the actual LFPR for the year. The average of the three projections for women is 77.2 percent, 2.9 percentage points above the actual LFPR for 2016.

The inclusion of the projection for 2008 can be questioned, since it is almost a decade in the past, but it is worth noting what economists expected in 2000, when the labor market was very strong. The bias in trends is mixed, since there is a small downward trend in LFPRs among men, so presumably in 2000 CBO would have given us a projection of men’s LFPR for 2016 that was somewhat lower than its projection for 2008. On the other hand, the trend for women was still rising, so a projection of women’s LFPR from 2000 for 2016 may have been somewhat higher than its projection for 2008.

In any case, it is clear that a decade ago the experts in the field believed that a substantially higher share of prime-age people would in the labor force today than we are currently seeing. It is certainly possible that they were wrong, but it’s also possible that the people claiming we are at full employment today are wrong. For my part, I’m with the experts.

Note: An earlier version put the unemployment rate at 4.7 percent.

Comments