March 01, 2017

By Dean Baker and Sarah Rawlins

Many of us had very mixed feelings about the Donald Trump Carrier show, where he got the Carrier Air Conditioner company to keep 800 jobs at one of its plants in Indiana instead of shipping them to Mexico. The state of Indiana, under then Governor Mike Pence, promised millions of dollars in tax concessions as an inducement. There were also reports of threats or promises directed towards Carrier’s parent company, United Technologies, which is a major military contractor.

While it was good to see these 800 workers keeping their jobs, this is not the way to protect U.S. manufacturing jobs. At the end of the day, 800 jobs is just a drop in the bucket in a labor force of 150 million or even among the 12.3 million people employed in manufacturing.

We can’t expect the president of the United States to be running around from factory to factory to make sure that manufacturing jobs stay in the United States. What we need is a policy.

Fortunately, there is a policy that would discourage companies from shutting down the shop and sending jobs elsewhere: it’s called “severance pay.” That might not sound new and sexy, because it isn’t, but it can radically alter the incentives for employers.

Suppose that workers were entitled to two weeks of severance pay for every year they work for a company. This means that workers who have been employed for over twenty years, as was the case with many of the Carrier workers, would be entitled to at least 40 weeks of severance pay.

This won’t get someone in their early fifties through to retirement, but it certainly is a nice going away gift. More importantly, it changes the incentives for company. If a company knows that it will be costly to lay off a large number of long-term workers, it might think harder about ways to keep them employed. This could mean continual retraining to maintain their skills and investment in the most modern equipment to ensure high levels of productivity.

Of course, if a company really has no productive use for a worker, it will still pay to lay them off, but this will not be a decision taken lightly. In effect, we are requiring the company to internalize the cost to the worker and society, since there is a high risk that an older worker who loses their job will be unemployed for a long period of time, collecting unemployment insurance and other benefits.

The conventional argument against severance pay is that it will discourage companies from hiring in the first place, since they don’t want to risk being stuck with older unproductive workers. While severance pay can clearly be too generous, and thereby impose too large a burden on employers, there is little reason to believe that moderate severance pay requirements have this effect.

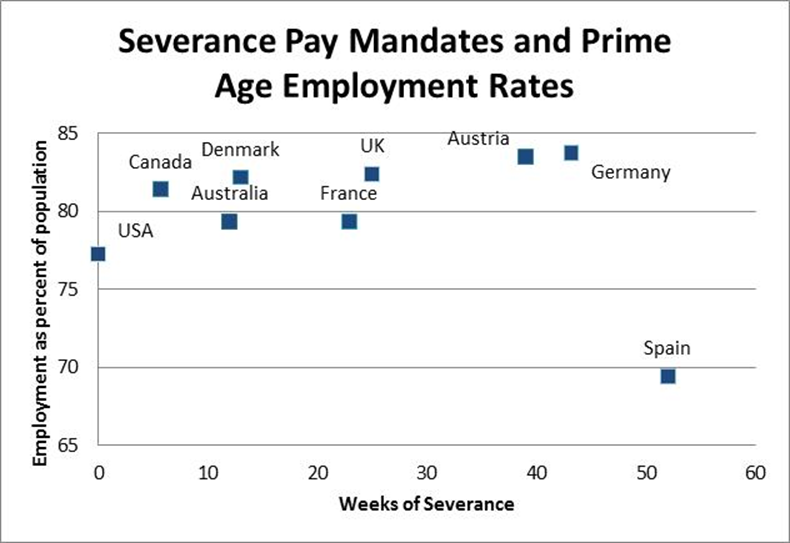

The figure below shows the employment rate of prime-age workers (ages 25–54) and severance pay requirements for the United States and several other major economies for workers who have been with the same employer for 20 years.

Source: OECD and ILO.

The United States is the only country among this group which has no severance pay requirements. (There are other wealthy countries that don’t require severance pay.) While the U.S. employment rate (EPOP) for prime-age workers is higher than Spain’s, which has not recovered from the Great Recession, it is well below most of the others. The EPOP for prime age workers in the United States is 6.5 percentage points below the EPOP in Germany, which requires 43 weeks of severance pay for long-term workers. It is more than 2.0 percentage points below the EPOP in France which requires 23 weeks of severance pay.

One argument sometimes raised is that severance pay requirements will give preference to older workers, keeping younger workers out of jobs. The evidence on this front is far from conclusive. Germany’s employment rate for people between the ages of 15 to 24 is 45.3 percent. In France it is just 27.9 percent. Both are well below the 48.6 employment rate for young people in the United States.

But both Germany and France have free college and actually give stipends to their students. This means that the vast majority of college students in these countries do not work, in contrast to the United States where the vast majority do work. Even with free college, Denmark has an EPOP of 55.4 percent, while Canada has an EPOP of 55.8 percent. In other words, severance pay for long-term workers doesn’t necessary act as a barrier to employment for younger workers.

One last point worth noting about severance pay: it can be put in place at the state level. This means that we don’t have to wait until the Democrats can retake Congress or the Republicans see the light, a state can impose a severance pay mandate on its own.

This certainly seems like a policy worth considering. It definitely is better than more Carrier shows.

Note: The size of the labor force was corrrected from “150,000 million” in an earlier version. Thanks Tim.

Comments