September 10, 2012

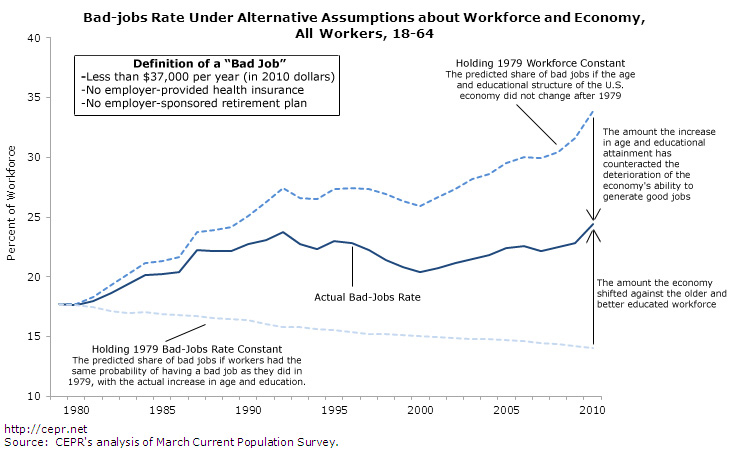

Our recent CEPR report “Bad Jobs on the Rise” found that between 1979 and 2010, the share of workers in a “bad job” increased from about 18 percent to about 24 percent. (In that report, we defined a bad job as one that pays less than $37,000 a year, lacks employer-provided health insurance, and lacks an employer-sponsored retirement plan. (For more details, see the report or this earlier post.)

The report emphasizes that the increase in bad jobs was especially disconcerting because the U.S. workforce was older and much better educated in 2010 than it had been in 1979. In the figure below, prepared by our CEPR colleague, Milla Sanes, we ask: What would the bad-jobs rate have been in 2010 without this age and educational upgrading of the workforce? The middle line shows the actual path of the bad-jobs rate over the period. The top line traces out the path the economy would have followed had we kept the same age and educational characteristics of the 1979 workforce, combined with the same losses in the economy’s ability to create good jobs. Under these assumptions, about one in three jobs (33.9 percent) would have been a bad job in 2010. The distance between the top two lines represents how much age and educational upgrading of the workforce helped to lower the bad-jobs rate.

(Click for larger version)

We can also ask a related question: What would the bad-jobs rate have been in 2010 if the economy had not lost any of its capacity to generate good jobs between 1979 and 2010? The bottom line in the figure traces out this path. If the economy had sustained the same capacity to produce good jobs that it had in 1979, and the workforce upgrading proceeded as it actually did between 1979 and 2010, the overall bad-jobs rate would have fallen to 14.1 percent in 2010. The distance between this line and the actual bad jobs rate captures just how much the economy has shifted against workers.