Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Not deliberately of course, but he once again used his column to demand that Congress take steps to cut Social Security and Medicare. He denounced the politicians who don’t share his agenda of making the lives of seniors harder as “cowards.” Okay, nothing unusual here.

But let’s take a step back into reality. The economy is hugely poorer today than it would have been if in the wake of the Great Recession we had effective stimulus. (Of course, we would be even better off if the folks running in the economy in the last decade knew some economics. Then they could have taken steps to counter the growth of the housing bubble, so we never would have had the Great Recession.)

The weak stimulus meant that unemployment was higher for a longer period of time than necessary. Many people lost skills and some ended up permanently unemployed. We also saw much less investment than we would have otherwise. As a result, the economy is more than 10 percent smaller today than had been projected back in 2008, before the depth of the crisis became apparent.

This loss in output comes to more than $6,000 per person annually. People who have taken Econ 101 know that it doesn’t make a difference to a person’s take-home pay if you tax their income by 10 percent or whether we cut their before-tax income by 10 percent. Robert Samuelson and his deficit hawk friends cut workers’ before-tax income by 10 percent with their push for austerity, which helped to put a check on effective stimulus. Now, they are deriding politicians as cowards for not wanting to go along with the other half of this agenda, cutting back the Social Security and Medicare benefits that these workers are counting on in their retirement.

It is also worth noting the warped logic in Samuelson and other deficit hawks arguments. Their measure of inter-generational equity is exclusively taxes. So if we hand down a wrecked environment, decrepit infrastructure, and shut down our schools, Samuelson would still have us scoring well on inter-generational equity as long as we haven’t raised taxes.

Samuelson and his Washington Post gang also are denialists in refusing to acknowledge that taxes are not the only way the government pays for things. The government grants patent and copyright monopolies, which effectively allow their holders to apply taxes on a wide range of items like prescription drugs, medical equipment, and software. In the case of prescription drugs alone, the gap between the patent prices we pay and the free market price comes close $400 billion a year (2 percent of GDP).

Presumably, Samuelson and the other deficit hawks don’t like to talk about patent and copyright monopolies because the beneficiaries are their friends. But people who actually care about economics and society’s well-being can’t be so selective in deciding to ignore such enormously important implicit taxes.

Note: Typos corrected from an earlier version, thanks Robert Salzberg.

Not deliberately of course, but he once again used his column to demand that Congress take steps to cut Social Security and Medicare. He denounced the politicians who don’t share his agenda of making the lives of seniors harder as “cowards.” Okay, nothing unusual here.

But let’s take a step back into reality. The economy is hugely poorer today than it would have been if in the wake of the Great Recession we had effective stimulus. (Of course, we would be even better off if the folks running in the economy in the last decade knew some economics. Then they could have taken steps to counter the growth of the housing bubble, so we never would have had the Great Recession.)

The weak stimulus meant that unemployment was higher for a longer period of time than necessary. Many people lost skills and some ended up permanently unemployed. We also saw much less investment than we would have otherwise. As a result, the economy is more than 10 percent smaller today than had been projected back in 2008, before the depth of the crisis became apparent.

This loss in output comes to more than $6,000 per person annually. People who have taken Econ 101 know that it doesn’t make a difference to a person’s take-home pay if you tax their income by 10 percent or whether we cut their before-tax income by 10 percent. Robert Samuelson and his deficit hawk friends cut workers’ before-tax income by 10 percent with their push for austerity, which helped to put a check on effective stimulus. Now, they are deriding politicians as cowards for not wanting to go along with the other half of this agenda, cutting back the Social Security and Medicare benefits that these workers are counting on in their retirement.

It is also worth noting the warped logic in Samuelson and other deficit hawks arguments. Their measure of inter-generational equity is exclusively taxes. So if we hand down a wrecked environment, decrepit infrastructure, and shut down our schools, Samuelson would still have us scoring well on inter-generational equity as long as we haven’t raised taxes.

Samuelson and his Washington Post gang also are denialists in refusing to acknowledge that taxes are not the only way the government pays for things. The government grants patent and copyright monopolies, which effectively allow their holders to apply taxes on a wide range of items like prescription drugs, medical equipment, and software. In the case of prescription drugs alone, the gap between the patent prices we pay and the free market price comes close $400 billion a year (2 percent of GDP).

Presumably, Samuelson and the other deficit hawks don’t like to talk about patent and copyright monopolies because the beneficiaries are their friends. But people who actually care about economics and society’s well-being can’t be so selective in deciding to ignore such enormously important implicit taxes.

Note: Typos corrected from an earlier version, thanks Robert Salzberg.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a good piece highlighting new research by Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Torslov, and Ludvig Wier indicating that multinationals may be shifting as much as 40 percent of their profits to tax havens. This is a pretty serious problem if we actually expect companies to pay their taxes.

As I have pointed in the past, there is actually a very simple mechanism that would pretty much block this sort of tax avoidance. If companies were required to give the government non-voting shares in an amount equal to the targeted tax rate, then it would be virtually impossible for them to escape their income tax liability without also defrauding their shareholders. But I realize this is probably too simple to be taken seriously.

The NYT had a good piece highlighting new research by Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Torslov, and Ludvig Wier indicating that multinationals may be shifting as much as 40 percent of their profits to tax havens. This is a pretty serious problem if we actually expect companies to pay their taxes.

As I have pointed in the past, there is actually a very simple mechanism that would pretty much block this sort of tax avoidance. If companies were required to give the government non-voting shares in an amount equal to the targeted tax rate, then it would be virtually impossible for them to escape their income tax liability without also defrauding their shareholders. But I realize this is probably too simple to be taken seriously.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s well-known that intellectuals have a hard time dealing with new ideas. And, for better or worse, the NYT’s editorial writers are intellectuals.

This made it painful to read its editorial criticizing the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) efforts to hasten the approval of new drugs. The piece makes many important points about the problems with an accelerated drug approval process. This increases the risk that drugs will be approved that are of little benefit and possibly even harmful.

While it notes the inevitable tradeoff between the desire to quickly make new drugs available to patients who can be helped and ensuring their safety and effectiveness, it misses the fundamental problem with having the testing done by a company with a financial interest in pushing drugs whether or not they are safe and effective.

This is an especially serious problem given the enormous asymmetry in the information available to the drug company doing the testing and both the FDA and the larger community of researchers. The decision to conceal or misrepresent test results has proven enormously harmful to the public in recent decades, most notably in reference to evidence that the new generation of opioid drugs are addictive.

The obvious solution to this problem would have the government take responsibility for funding clinical testing. The government could still contract out the testing process, but if it took possession of all rights to the drugs, so that they would be available as generics when they were approved, there would be no one with an interest in misrepresenting the research results. (This would not preclude drug companies for paying for their own tests on drugs to which they maintained patent monopolies, but these drugs would be subject to much greater scrutiny for approval. They would also face the risk of competing with drugs that are every bit as effective selling at generic prices.)

While publicly funded drug testing would seem an obvious way to deal with a serious health issue, it would require the sort of new thinking that intellectuals find very difficult.

It’s well-known that intellectuals have a hard time dealing with new ideas. And, for better or worse, the NYT’s editorial writers are intellectuals.

This made it painful to read its editorial criticizing the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) efforts to hasten the approval of new drugs. The piece makes many important points about the problems with an accelerated drug approval process. This increases the risk that drugs will be approved that are of little benefit and possibly even harmful.

While it notes the inevitable tradeoff between the desire to quickly make new drugs available to patients who can be helped and ensuring their safety and effectiveness, it misses the fundamental problem with having the testing done by a company with a financial interest in pushing drugs whether or not they are safe and effective.

This is an especially serious problem given the enormous asymmetry in the information available to the drug company doing the testing and both the FDA and the larger community of researchers. The decision to conceal or misrepresent test results has proven enormously harmful to the public in recent decades, most notably in reference to evidence that the new generation of opioid drugs are addictive.

The obvious solution to this problem would have the government take responsibility for funding clinical testing. The government could still contract out the testing process, but if it took possession of all rights to the drugs, so that they would be available as generics when they were approved, there would be no one with an interest in misrepresenting the research results. (This would not preclude drug companies for paying for their own tests on drugs to which they maintained patent monopolies, but these drugs would be subject to much greater scrutiny for approval. They would also face the risk of competing with drugs that are every bit as effective selling at generic prices.)

While publicly funded drug testing would seem an obvious way to deal with a serious health issue, it would require the sort of new thinking that intellectuals find very difficult.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Dentists in the United States earn on average a bit more than $200,000 a year. This is roughly twice the average in other wealthy countries like Canada and Germany, although still less than the $250,000 average for doctors. Their pay is more than 13 times what a minimum wage worker would take home in a year.

The conventional story for this sort of inequality is that dentists have highly valued skills in today’s economy, whereas most minimum wage workers don’t. As an alternative, let me suggest that we have a whole array of policies, from trade, immigration, labor, and monetary policies that are designed to keep the pay of minimum wage workers down. By contrast, dentists and other highly paid professionals are winners from these policies. (Yes, this is the topic of my [free] book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Are Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

The Washington Post had a piece on the limited access to dental care in many parts of the United States, focusing on a small town in rural West Virginia. While it is an interesting piece, one of the items that is striking is that it never once mentions the possibility of bringing in more foreign dentists to alleviate the shortage it describes and to bring down the price of dental care. (Yes, that means dentists get paid less.)

The Post has run many pieces over the years on how immigrant workers are needed to ensure an adequate supply of farm labor, high tech workers, and even seasonal workers at vacation resorts. It is a bit hard to understand why it would not occur to its reporters and editors to see foreign workers as a possible route for alleviating a shortage of dentists.

This is especially striking since the United States has strong protectionist barriers in place that raise the cost of dental care. We prohibit dentists from practicing in the United States unless they graduate from a US dental school. (We recently have allowed graduates of a limited number of Canadian dental schools to practice in the US also.)

It is absurd to imagine that there are not tens of thousands of well-qualified dentists in places like Germany, France, and other countries. Many would likely welcome the opportunity to double their pay by working in the United States, at least for a few years, if not their whole career.

Needless to say, we can count on much more genuflecting in the Post and elsewhere about designing policies that can reverse inequality. It’s fascinating to see how they refuse to ever discuss the policies that cause inequality.

Dentists in the United States earn on average a bit more than $200,000 a year. This is roughly twice the average in other wealthy countries like Canada and Germany, although still less than the $250,000 average for doctors. Their pay is more than 13 times what a minimum wage worker would take home in a year.

The conventional story for this sort of inequality is that dentists have highly valued skills in today’s economy, whereas most minimum wage workers don’t. As an alternative, let me suggest that we have a whole array of policies, from trade, immigration, labor, and monetary policies that are designed to keep the pay of minimum wage workers down. By contrast, dentists and other highly paid professionals are winners from these policies. (Yes, this is the topic of my [free] book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Are Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

The Washington Post had a piece on the limited access to dental care in many parts of the United States, focusing on a small town in rural West Virginia. While it is an interesting piece, one of the items that is striking is that it never once mentions the possibility of bringing in more foreign dentists to alleviate the shortage it describes and to bring down the price of dental care. (Yes, that means dentists get paid less.)

The Post has run many pieces over the years on how immigrant workers are needed to ensure an adequate supply of farm labor, high tech workers, and even seasonal workers at vacation resorts. It is a bit hard to understand why it would not occur to its reporters and editors to see foreign workers as a possible route for alleviating a shortage of dentists.

This is especially striking since the United States has strong protectionist barriers in place that raise the cost of dental care. We prohibit dentists from practicing in the United States unless they graduate from a US dental school. (We recently have allowed graduates of a limited number of Canadian dental schools to practice in the US also.)

It is absurd to imagine that there are not tens of thousands of well-qualified dentists in places like Germany, France, and other countries. Many would likely welcome the opportunity to double their pay by working in the United States, at least for a few years, if not their whole career.

Needless to say, we can count on much more genuflecting in the Post and elsewhere about designing policies that can reverse inequality. It’s fascinating to see how they refuse to ever discuss the policies that cause inequality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post may have wanted to make this point more clearly in reporting on Donald Trump’s statements as he headed off to the G–7 meeting in Canada. The piece noted Trump’s Twitter comment:

“‘Take down your tariffs & barriers or we will more than match you!’ he wrote on Twitter. He did not specify what products he could seek to target.”

Tariffs are of course excise taxes. The government imposes taxes on a specific product. In the 19th century, these taxes were the major source of revenue for the US government.

The imposition of tariffs may be a useful strategy to force concessions from trading partners, but that seems an unlikely outcome given Trump’s ill-defined and continually changing demands. In any case, his main weapon is to make US consumers pay more for a wide range of products.

This piece also contains the bizarre assertion that:

“His [Trump’s] view is that other countries have imposed unfair tariffs limiting US imports for decades but that the United States has unwittingly allowed those countries to bring low-cost goods into the United States, hurting US companies and American workers.”

The Washington Post’s reporters do not know what Trump’s “view” is or that he even has anything that can be called a view. They know what he says and does. This is what real newspapers report. Leave the mind reading to the tabloids.

The Washington Post may have wanted to make this point more clearly in reporting on Donald Trump’s statements as he headed off to the G–7 meeting in Canada. The piece noted Trump’s Twitter comment:

“‘Take down your tariffs & barriers or we will more than match you!’ he wrote on Twitter. He did not specify what products he could seek to target.”

Tariffs are of course excise taxes. The government imposes taxes on a specific product. In the 19th century, these taxes were the major source of revenue for the US government.

The imposition of tariffs may be a useful strategy to force concessions from trading partners, but that seems an unlikely outcome given Trump’s ill-defined and continually changing demands. In any case, his main weapon is to make US consumers pay more for a wide range of products.

This piece also contains the bizarre assertion that:

“His [Trump’s] view is that other countries have imposed unfair tariffs limiting US imports for decades but that the United States has unwittingly allowed those countries to bring low-cost goods into the United States, hurting US companies and American workers.”

The Washington Post’s reporters do not know what Trump’s “view” is or that he even has anything that can be called a view. They know what he says and does. This is what real newspapers report. Leave the mind reading to the tabloids.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Many pundit types were thrown for a loop by the Labor Department’s release of its Contingent Worker Survey yesterday. The survey, the first one since 2005, showed no increase in the percentage of workers employed as independent contractors, such as those who work for Uber and Lyft.

While that didn’t surprise those of us who follow the data closely, the release did seem to catch some of the proselytizers of the gig economy by surprise. It turns out that replacing taxi drivers (many of whom are contract workers) by contract workers for Uber and Lyft, has not transformed the labor market.

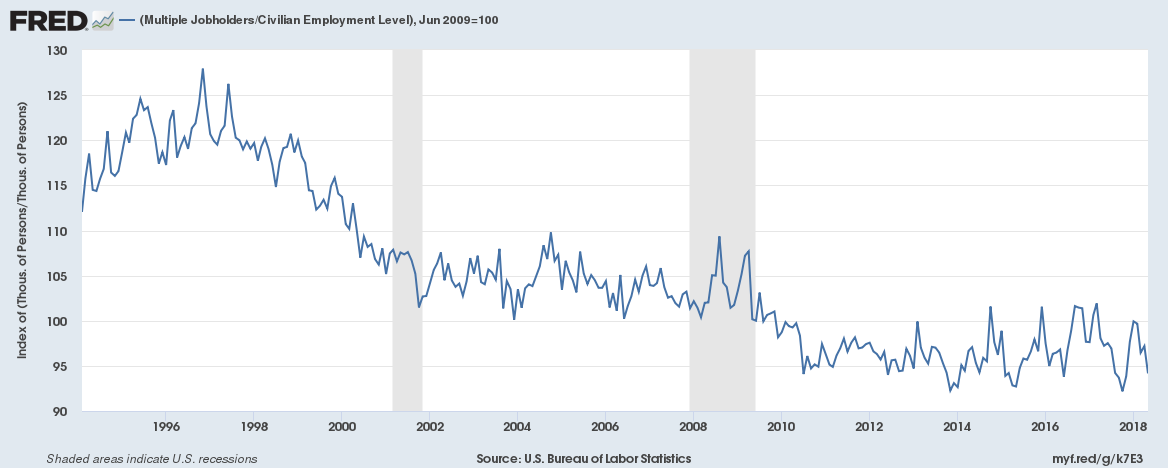

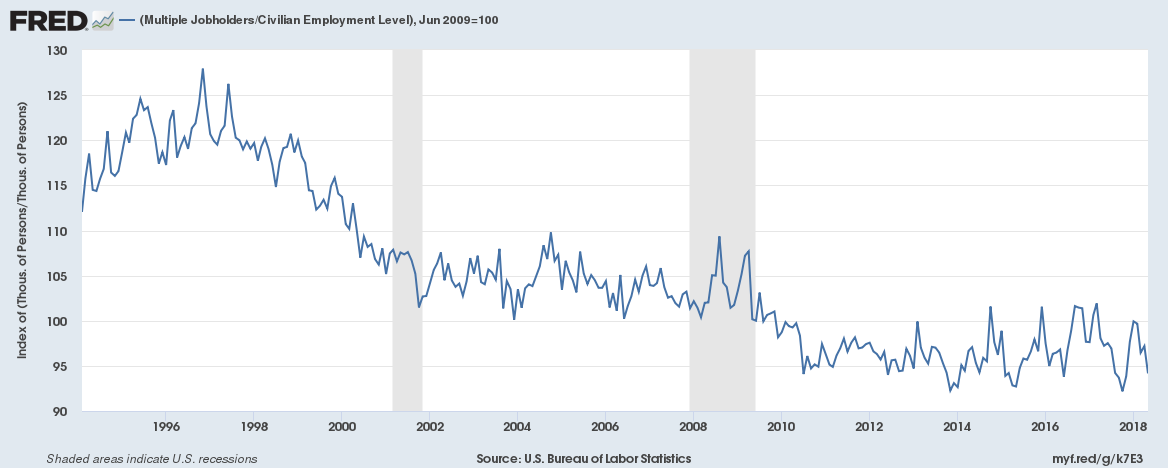

As has been pointed by out by Larry Mishel and others, most of the people doing gig economy work do it as a sidebar, in addition to their main jobs. But it is worth noting that even here the data points to a decline in the percentage of workers employed in multiple jobs over the last quarter century.

So even insofar as workers are turning to Uber or TaskRabbit to supplement their income, it seems to a large extent it is substituting for other side work they used to do. It seems the gig economy means much more to pundits than to workers.

Many pundit types were thrown for a loop by the Labor Department’s release of its Contingent Worker Survey yesterday. The survey, the first one since 2005, showed no increase in the percentage of workers employed as independent contractors, such as those who work for Uber and Lyft.

While that didn’t surprise those of us who follow the data closely, the release did seem to catch some of the proselytizers of the gig economy by surprise. It turns out that replacing taxi drivers (many of whom are contract workers) by contract workers for Uber and Lyft, has not transformed the labor market.

As has been pointed by out by Larry Mishel and others, most of the people doing gig economy work do it as a sidebar, in addition to their main jobs. But it is worth noting that even here the data points to a decline in the percentage of workers employed in multiple jobs over the last quarter century.

So even insofar as workers are turning to Uber or TaskRabbit to supplement their income, it seems to a large extent it is substituting for other side work they used to do. It seems the gig economy means much more to pundits than to workers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s great that the Washington Post has so many reporters with mind reading abilities. As a result, we know that Trump is “convinced that his attendance at the G–7 summit is essential.”

Good to know that Trump is convinced of this fact. Otherwise, we might just think it would be too politically embarrassing for him not to show up just after a statement from G–7 (minus the US) finance ministers condemned his trade policy.

If news outlets like the Post didn’t have reporters with mind reading abilities, the rest of us would just know what politicians say and do. We wouldn’t be able to learn what they actually think.

It’s great that the Washington Post has so many reporters with mind reading abilities. As a result, we know that Trump is “convinced that his attendance at the G–7 summit is essential.”

Good to know that Trump is convinced of this fact. Otherwise, we might just think it would be too politically embarrassing for him not to show up just after a statement from G–7 (minus the US) finance ministers condemned his trade policy.

If news outlets like the Post didn’t have reporters with mind reading abilities, the rest of us would just know what politicians say and do. We wouldn’t be able to learn what they actually think.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That would have been an appropriate headline for an NYT article in which Alex Azar, the head of the Department of Health and Human Sevices, claimed that the Trump Administration’s policies are not responsible for double-digit price increases for insurance policies in the exchange. If Azar really believes what he claims, he doesn’t understand the basics of insurance.

The Trump Administration has adopted policies that allow more healthy people to opt out of the exchanges’ insurance pool. It created an expanded set of short-term bare-bones policies that would be attractive to people in good health as an alternative to the policies available in the exchanges. Congress also passed legislation that ends enforcement of the individual mandate, which means that healthy have more incentive not to sign up for insurance at all.

Since per person health care costs are rising at less than a 5.0 percent annual rate, the only explanation for the double-digit premium rate increases in the exchanges is a change in the mix of people getting insurance, with the pools becoming less healthy. (The Affordable Care Act was explicitly designed to create a single insurance pool so that the premiums paid by relatively healthy people subsidize the less healthy.) If we accept Mr. Azar’s assertions at face value, that the Trump Administration’s policies are not responsible for the rapid rise in premiums, it indicates he does not understand how insurance markets work.

That would have been an appropriate headline for an NYT article in which Alex Azar, the head of the Department of Health and Human Sevices, claimed that the Trump Administration’s policies are not responsible for double-digit price increases for insurance policies in the exchange. If Azar really believes what he claims, he doesn’t understand the basics of insurance.

The Trump Administration has adopted policies that allow more healthy people to opt out of the exchanges’ insurance pool. It created an expanded set of short-term bare-bones policies that would be attractive to people in good health as an alternative to the policies available in the exchanges. Congress also passed legislation that ends enforcement of the individual mandate, which means that healthy have more incentive not to sign up for insurance at all.

Since per person health care costs are rising at less than a 5.0 percent annual rate, the only explanation for the double-digit premium rate increases in the exchanges is a change in the mix of people getting insurance, with the pools becoming less healthy. (The Affordable Care Act was explicitly designed to create a single insurance pool so that the premiums paid by relatively healthy people subsidize the less healthy.) If we accept Mr. Azar’s assertions at face value, that the Trump Administration’s policies are not responsible for the rapid rise in premiums, it indicates he does not understand how insurance markets work.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión