Housing rent has been outpacing the overall rate of inflation in recent years. This is worth noting both because it is a large portion of the consumption basket and rents do not tend to follow other prices. Rent is primarily a function of the shortage of available units. It does not respond in any immediate way to wage pressures, like other components in the consumption basket. Rental inflation will also not be slowed by higher interest rates. In fact, by reducing construction, higher interest rates may further tighten the supply of housing, leading to higher rental inflation.

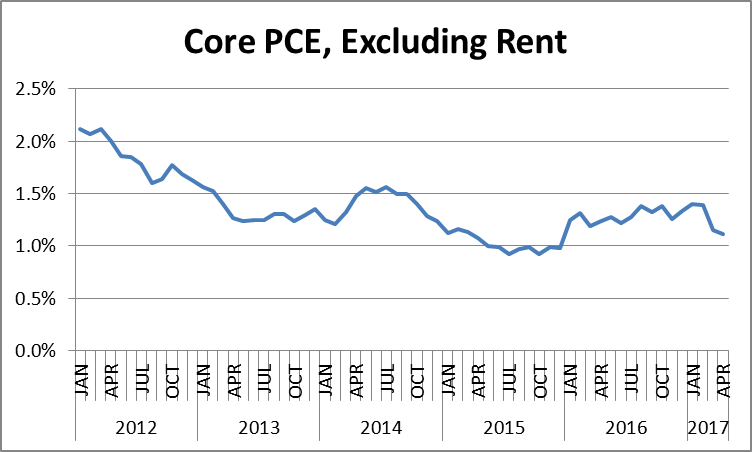

If we look at the core personal consumption expenditure deflator excluding rent, it is both well below the Fed’s 2.0 percent target and, if anything, is trending lower over the last few years.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This raises the question millions are asking: why is the Fed raising interest rates? We know this keeps people from getting jobs and workers, especially those at the bottom of the wage distribution, from getting pay increases. With no problems with inflation on the horizon, this looks like lots of pain for no obvious gain.

Note: An earlier version had the months improperly labeled.

Housing rent has been outpacing the overall rate of inflation in recent years. This is worth noting both because it is a large portion of the consumption basket and rents do not tend to follow other prices. Rent is primarily a function of the shortage of available units. It does not respond in any immediate way to wage pressures, like other components in the consumption basket. Rental inflation will also not be slowed by higher interest rates. In fact, by reducing construction, higher interest rates may further tighten the supply of housing, leading to higher rental inflation.

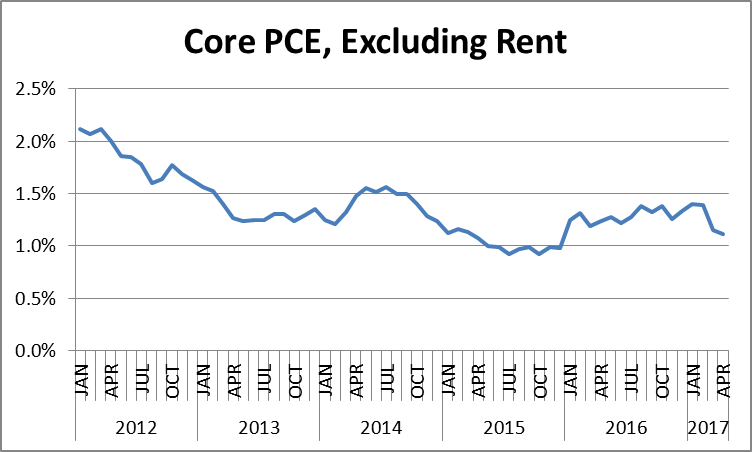

If we look at the core personal consumption expenditure deflator excluding rent, it is both well below the Fed’s 2.0 percent target and, if anything, is trending lower over the last few years.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This raises the question millions are asking: why is the Fed raising interest rates? We know this keeps people from getting jobs and workers, especially those at the bottom of the wage distribution, from getting pay increases. With no problems with inflation on the horizon, this looks like lots of pain for no obvious gain.

Note: An earlier version had the months improperly labeled.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Using arithmetic in economic policy debates is always dangerous, but that would seem to be the implication of the NYT’s designation of Germany’s $64.8 billion trade surplus with the United States as “mammoth.” Since China’s $347.0 billion trade surplus was more than five times as large, it would seem that China’s surplus has to be five times massive. It usually is not talked about that way in the NYT and elsewhere.

Remarkably, the piece never focused on the real explanation for Germany’s large trade surplus. It insists on running budget surpluses, even though there continues to be widespread unemployment throughout the euro zone. This policy is far more harmful to the other euro zone countries than the United States.

If Germany ran budget deficits it would directly pull in more imports from its euro zone partners (and the United States), thereby boosting demand and output in France, Italy, Greece and elsewhere. It would also see somewhat more rapid inflation, which would make other countries’ goods and services relatively more competitive. Also, a more rapidly growing euro zone economy would likely increase the value of the euro, making U.S. goods and services more competitive compared with those produced in the euro zone.

Germany doesn’t boost demand in this way apparently because the country is tied up with nearly century old superstitions about inflation. Just as many people in the United States deny global warming in spite of massive evidence that it is real and humans are causing it, millions of Germans, including those in leadership positions, claim that modest increases in the inflation rate could lead to the sort of hyper-inflation the country experienced under Weimar, following World War I. There is absolutely no evidence to support this view, but it seems to guide German economic policy.

Using arithmetic in economic policy debates is always dangerous, but that would seem to be the implication of the NYT’s designation of Germany’s $64.8 billion trade surplus with the United States as “mammoth.” Since China’s $347.0 billion trade surplus was more than five times as large, it would seem that China’s surplus has to be five times massive. It usually is not talked about that way in the NYT and elsewhere.

Remarkably, the piece never focused on the real explanation for Germany’s large trade surplus. It insists on running budget surpluses, even though there continues to be widespread unemployment throughout the euro zone. This policy is far more harmful to the other euro zone countries than the United States.

If Germany ran budget deficits it would directly pull in more imports from its euro zone partners (and the United States), thereby boosting demand and output in France, Italy, Greece and elsewhere. It would also see somewhat more rapid inflation, which would make other countries’ goods and services relatively more competitive. Also, a more rapidly growing euro zone economy would likely increase the value of the euro, making U.S. goods and services more competitive compared with those produced in the euro zone.

Germany doesn’t boost demand in this way apparently because the country is tied up with nearly century old superstitions about inflation. Just as many people in the United States deny global warming in spite of massive evidence that it is real and humans are causing it, millions of Germans, including those in leadership positions, claim that modest increases in the inflation rate could lead to the sort of hyper-inflation the country experienced under Weimar, following World War I. There is absolutely no evidence to support this view, but it seems to guide German economic policy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I kind of love how ridiculous things get repeated endlessly by people who claim to be informed. In his NYT column, Avik Roy warned us against taking seriously the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projections of a surge in the uninsured under the Republican health care plan.

“First, some caution regarding the C.B.O.’s numbers. The C.B.O. is chock-full of committed and talented public servants, but the agency is neither omniscient nor infallible. In 2010, when the Affordable Care Act was signed into law by President Barack Obama, the C.B.O. predicted that by 2017, 23 million Americans would be enrolled in the law’s new insurance exchanges. Only about 11 million actually are.

“That’s because the C.B.O. failed to account for how the A.C.A.’s insurance regulations would drive premiums up for relatively healthy individuals. A new study by researchers at the Department of Health and Human Services finds that for people buying coverage on their own, premiums have more than doubled in the Obamacare era. Most adversely affected have been those whose incomes — while modest — were not low enough to qualify for sufficient amounts of the A.C.A.’s insurance subsidies.

“While the C.B.O. was overly optimistic in 2010 about Obamacare, there’s a strong case that it is being overly pessimistic about the new House bill, the American Health Care Act.”

Actually, CBO was overly pessimistic about Obamacare. If we look to CBO’s last report on the Affordable Care Act, before the exchanges began operation in 2014, it projected that there would be 29 million people uninsured as of 2017 (Table 3). In its most recent analysis, it puts the number of uninsured in 2017 at 26 million (Table 4). In other words, the number of people who are uninsured under the ACA is 3 million fewer than CBO had predicted back in 2012.

In what world is overestimating the number of uninsured “overly optimistic?” It is true that fewer people are in the exchanges than CBO expected. This is due to the fact that more people have qualified for Medicaid and also more people are receiving employer-provided insurance, as fewer companies than expected dropped coverage.

But, so what? The point was to get people insured, not necessarily to have them insured through the exchanges.

So remember the facts when you read Roy’s NYT column giving his prognostications for the Republican health care reform. Here’s a guy who couldn’t even bother to get the basic numbers on the ACA right.

I kind of love how ridiculous things get repeated endlessly by people who claim to be informed. In his NYT column, Avik Roy warned us against taking seriously the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projections of a surge in the uninsured under the Republican health care plan.

“First, some caution regarding the C.B.O.’s numbers. The C.B.O. is chock-full of committed and talented public servants, but the agency is neither omniscient nor infallible. In 2010, when the Affordable Care Act was signed into law by President Barack Obama, the C.B.O. predicted that by 2017, 23 million Americans would be enrolled in the law’s new insurance exchanges. Only about 11 million actually are.

“That’s because the C.B.O. failed to account for how the A.C.A.’s insurance regulations would drive premiums up for relatively healthy individuals. A new study by researchers at the Department of Health and Human Services finds that for people buying coverage on their own, premiums have more than doubled in the Obamacare era. Most adversely affected have been those whose incomes — while modest — were not low enough to qualify for sufficient amounts of the A.C.A.’s insurance subsidies.

“While the C.B.O. was overly optimistic in 2010 about Obamacare, there’s a strong case that it is being overly pessimistic about the new House bill, the American Health Care Act.”

Actually, CBO was overly pessimistic about Obamacare. If we look to CBO’s last report on the Affordable Care Act, before the exchanges began operation in 2014, it projected that there would be 29 million people uninsured as of 2017 (Table 3). In its most recent analysis, it puts the number of uninsured in 2017 at 26 million (Table 4). In other words, the number of people who are uninsured under the ACA is 3 million fewer than CBO had predicted back in 2012.

In what world is overestimating the number of uninsured “overly optimistic?” It is true that fewer people are in the exchanges than CBO expected. This is due to the fact that more people have qualified for Medicaid and also more people are receiving employer-provided insurance, as fewer companies than expected dropped coverage.

But, so what? The point was to get people insured, not necessarily to have them insured through the exchanges.

So remember the facts when you read Roy’s NYT column giving his prognostications for the Republican health care reform. Here’s a guy who couldn’t even bother to get the basic numbers on the ACA right.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a piece discussing the efforts by various industry groups to ensure that they are not hurt by measures that reduce prescription drug prices. At one point, it listed some of these measures, noting a bill co-sponsored by Senator Bernie Sanders, which would allow drugs to be imported from Canada.

It is worth noting that this bill, which is co-sponsored by sixteen other senators including Elizabeth Warren, Sherrod Brown, and Kirsten Gillibrand, also includes mechanisms that would reduce the cost of drugs by not granting them patent monopolies that make their price high in the first place. One proposal would create a prize fund, which would allow for the patents on important new drugs to be purchased by the government and placed in the public domain. They could then be sold as generics as soon as they are put on the market.

The other provision would have the government finance some clinical trials of drugs after securing all patent rights. In this case, also the new drugs would be sold as generics. By paying for the trials (which would be conducted by private companies under contract), the government would be able to require that all test results were in the public domain.

This would allow doctors and other researchers to be able to determine if a particular drug was better for men than women, or appeared to cause bad reactions when mixed with other drugs. As it stands now, drug companies only have an incentive to publicly disclose information that they think will help them market their drugs. If the government paid for some number of clinical trials, it could help to set a new standard of disclosure with its practices, in addition to making new drugs available at generic prices.

The NYT ran a piece discussing the efforts by various industry groups to ensure that they are not hurt by measures that reduce prescription drug prices. At one point, it listed some of these measures, noting a bill co-sponsored by Senator Bernie Sanders, which would allow drugs to be imported from Canada.

It is worth noting that this bill, which is co-sponsored by sixteen other senators including Elizabeth Warren, Sherrod Brown, and Kirsten Gillibrand, also includes mechanisms that would reduce the cost of drugs by not granting them patent monopolies that make their price high in the first place. One proposal would create a prize fund, which would allow for the patents on important new drugs to be purchased by the government and placed in the public domain. They could then be sold as generics as soon as they are put on the market.

The other provision would have the government finance some clinical trials of drugs after securing all patent rights. In this case, also the new drugs would be sold as generics. By paying for the trials (which would be conducted by private companies under contract), the government would be able to require that all test results were in the public domain.

This would allow doctors and other researchers to be able to determine if a particular drug was better for men than women, or appeared to cause bad reactions when mixed with other drugs. As it stands now, drug companies only have an incentive to publicly disclose information that they think will help them market their drugs. If the government paid for some number of clinical trials, it could help to set a new standard of disclosure with its practices, in addition to making new drugs available at generic prices.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There is a widely held view among policy types that drug companies would act like total morons if they did research under a government contract as opposed to having the lure of a patent monopoly. Apparently, this is not true, since it seems that the French drug company Sanofi has developed an effective vaccine doing research that was funded by the U.S. Army. So the theory of knowledge holding that otherwise intelligent people become worthless hacks in the process of drug development if the government is the source of funding is apparently not true.

Of course, this is not entirely a clean test of the proposition since Sanofi will still be given exclusive rights to market the vaccine. Apparently, even when the government is paying for the research upfront and taking all the risk (if the vaccine doesn’t work, Sanofi has still been paid), drug companies still need monopolies, because hey, how could they survive in a free market?

If people in policy positions and economists were interested in free markets, they would be very upset by this story.

There is a widely held view among policy types that drug companies would act like total morons if they did research under a government contract as opposed to having the lure of a patent monopoly. Apparently, this is not true, since it seems that the French drug company Sanofi has developed an effective vaccine doing research that was funded by the U.S. Army. So the theory of knowledge holding that otherwise intelligent people become worthless hacks in the process of drug development if the government is the source of funding is apparently not true.

Of course, this is not entirely a clean test of the proposition since Sanofi will still be given exclusive rights to market the vaccine. Apparently, even when the government is paying for the research upfront and taking all the risk (if the vaccine doesn’t work, Sanofi has still been paid), drug companies still need monopolies, because hey, how could they survive in a free market?

If people in policy positions and economists were interested in free markets, they would be very upset by this story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay, it’s Memorial Day weekend and maybe the regular crew is on vacation at the NYT, but come on, you don’t print GDP growth numbers without adjusting for inflation. The NYT committed this cardinal sin in a column by Simon Tilford telling readers that the United Kingdom actually has a pretty mediocre economy that is likely to perform even worse post-Brexit.

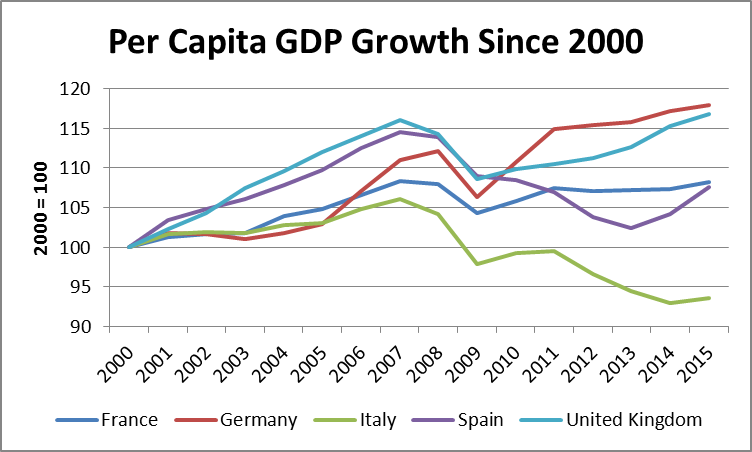

While I’m inclined to agree with the basic argument (with the qualification that there may be a dividend from sinking the financial sector), two of the graphs accompanying the piece likely left readers scratching their heads. The first showed per capita GDP growth since 2000 for Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the UK. The moral was that the UK was not doing much better than France, which is supposed to have a moribund economy according to popular legend. The second showed a similar story with real wages.

The problem is that neither graph is adjusted for inflation. As a result, we see the shocking story that per capita GDP growth for both France and the UK have increased by more than 35 percent since 2000. Germany’s per capita GDP has increased by almost 50 percent.

That would be great news if true, but it’s not. Here’s the real picture.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

After adjusting for inflation, UK does a bit better relative to France, but 16 percent per capita GDP growth in 15 years is not much to brag about. (I suspect the picture looks less favorable to the UK if we adjust for changes in hours worked.) The story of Italy is especially striking. On a per capita basis, it is almost 7.0 percent poorer than it was at the turn of the century.

Okay, it’s Memorial Day weekend and maybe the regular crew is on vacation at the NYT, but come on, you don’t print GDP growth numbers without adjusting for inflation. The NYT committed this cardinal sin in a column by Simon Tilford telling readers that the United Kingdom actually has a pretty mediocre economy that is likely to perform even worse post-Brexit.

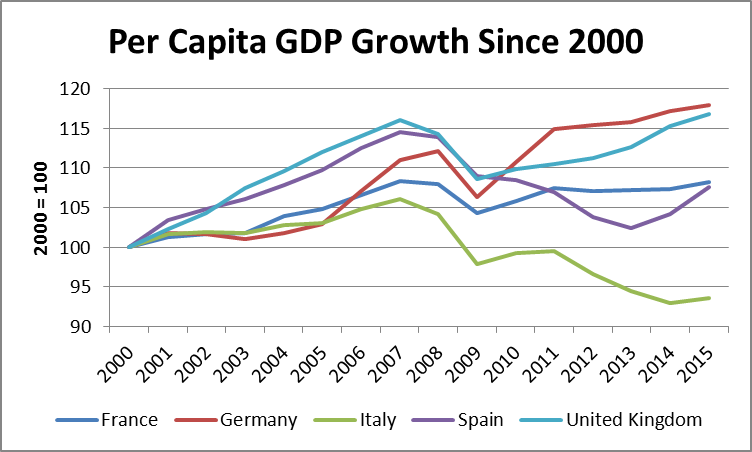

While I’m inclined to agree with the basic argument (with the qualification that there may be a dividend from sinking the financial sector), two of the graphs accompanying the piece likely left readers scratching their heads. The first showed per capita GDP growth since 2000 for Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the UK. The moral was that the UK was not doing much better than France, which is supposed to have a moribund economy according to popular legend. The second showed a similar story with real wages.

The problem is that neither graph is adjusted for inflation. As a result, we see the shocking story that per capita GDP growth for both France and the UK have increased by more than 35 percent since 2000. Germany’s per capita GDP has increased by almost 50 percent.

That would be great news if true, but it’s not. Here’s the real picture.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

After adjusting for inflation, UK does a bit better relative to France, but 16 percent per capita GDP growth in 15 years is not much to brag about. (I suspect the picture looks less favorable to the UK if we adjust for changes in hours worked.) The story of Italy is especially striking. On a per capita basis, it is almost 7.0 percent poorer than it was at the turn of the century.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post columnist Steven Pearlstein urged people to be moderate in their criticisms of the Trump budget. In an obvious reference to plans to eliminate support for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the National Endowment for the Arts, he argues:

“I like Masterpiece Theatre and a Beethoven symphony as much as the next upper-middle-class professional, but I can see why some people might wonder why their tax dollars should subsidize my taste for British drama and classical music but not their preference for NASCAR and country western music.”

Actually, the Trump budget will not touch the major source of taxpayer subsidies for the sort of culture enjoyed primarily by higher income people. Last year the federal government gave $445 million to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (0.013 percent of total spending). It gave $150 million to the National Endowment for the Arts (0.004 percent of total spending).

By contrast, if a billionaire opts to give $1 billion to a local museum or orchestra, they will be able to write off roughly $400 million of this contribution from their taxes. The amount that taxpayers shell out through subsidizing these donations dwarfs the amount that they pay through direct federal support. The difference is that there is some public voice in where the money goes when the federal government appropriates it. The allocation of the tax subsidy is completely determined by the billionaires.

Washington Post columnist Steven Pearlstein urged people to be moderate in their criticisms of the Trump budget. In an obvious reference to plans to eliminate support for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the National Endowment for the Arts, he argues:

“I like Masterpiece Theatre and a Beethoven symphony as much as the next upper-middle-class professional, but I can see why some people might wonder why their tax dollars should subsidize my taste for British drama and classical music but not their preference for NASCAR and country western music.”

Actually, the Trump budget will not touch the major source of taxpayer subsidies for the sort of culture enjoyed primarily by higher income people. Last year the federal government gave $445 million to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (0.013 percent of total spending). It gave $150 million to the National Endowment for the Arts (0.004 percent of total spending).

By contrast, if a billionaire opts to give $1 billion to a local museum or orchestra, they will be able to write off roughly $400 million of this contribution from their taxes. The amount that taxpayers shell out through subsidizing these donations dwarfs the amount that they pay through direct federal support. The difference is that there is some public voice in where the money goes when the federal government appropriates it. The allocation of the tax subsidy is completely determined by the billionaires.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Matt O’Brien’s Wonkblog piece might have misled readers on Republicans views on the role of government. O’Brien argued that the reason that the Republicans have such a hard time designing a workable health care plan is:

“Republicans are philosophically opposed to redistribution, but health care is all about redistribution.”

This is completely untrue. Republicans push policies all the time that redistribute income upward. They are strong supporters of longer and stronger patent and copyright protection that make ordinary people pay more for everything from prescription drugs and medical equipment to software and video games. They routinely support measures that limit competition in the financial industry (for example, trying to ban state-run retirement plans) that will put more money in the pockets of the financial industry. And they support Federal Reserve Board policy that prevents people from getting jobs and pay increases, thereby redistributing income to employers and higher paid workers.

Republicans are just fine with having the government intervene in markets to redistribute income upward, they just don’t like policies that are designed to help the poor and middle class at the expense of the rich. It is wrong to imply, as O’Brien does, they have any other principles in these debates than giving as much money as possible to the rich. (Yes, this is the theme of my book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer [it’s free].)

Matt O’Brien’s Wonkblog piece might have misled readers on Republicans views on the role of government. O’Brien argued that the reason that the Republicans have such a hard time designing a workable health care plan is:

“Republicans are philosophically opposed to redistribution, but health care is all about redistribution.”

This is completely untrue. Republicans push policies all the time that redistribute income upward. They are strong supporters of longer and stronger patent and copyright protection that make ordinary people pay more for everything from prescription drugs and medical equipment to software and video games. They routinely support measures that limit competition in the financial industry (for example, trying to ban state-run retirement plans) that will put more money in the pockets of the financial industry. And they support Federal Reserve Board policy that prevents people from getting jobs and pay increases, thereby redistributing income to employers and higher paid workers.

Republicans are just fine with having the government intervene in markets to redistribute income upward, they just don’t like policies that are designed to help the poor and middle class at the expense of the rich. It is wrong to imply, as O’Brien does, they have any other principles in these debates than giving as much money as possible to the rich. (Yes, this is the theme of my book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer [it’s free].)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión