Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Alec MacGillis had an interesting profile of Tom Nides in the New Yorker. Nides is currently a top executive at Morgan Stanley who is frequently mentioned as a leading contender for Treasury Secretary or other high level position in the Clinton administration. The piece ends with this remarkable section:

“But Barney Frank, the former Democratic congressman—who, despite having co-authored Dodd-Frank, is not opposed to former Wall Street executives working in Washington—told me that, in a friendly debate that he and Nides have conducted in recent years, Nides has vigorously defended Wall Street compensation: ‘He said, “These are extremely talented people who do valuable work.’”‘”

This one deserves a bit of thought. Remember, we’re talking about the top people at major banks, like former Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf. These people earns tens of millions of dollars a year. The folks at the hedge funds and private equity funds can earn hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

When we think about their talents, remember these are exactly the group of people that fueled the housing bubble with their fraudulent loans and bad securities. The country has paid and continues to pay an enormous price for this episode. If we look at the Congressional Budget Office’s estimates of potential GDP, its current estimate for 2016 is more than ten percent below its projection of 2016 potential GDP back in 2008, before the crash.

To get an idea of the magnitude of 10 percent of GDP, this is roughly 2.5 times the size of the Social Security tax. There are any number of people in Washington who would go absolutely nuts over the suggestion that we raise the Social Security tax by 2.0 percentage points (even if phased in over a decade). Imagine raising it by 30 percentage points. This would have the equivalent impact on people’s income as the long-term damage from the collapse of the housing bubble.

It is also worth noting that the Wall Street gang did not do even do well from the standpoint of the firms and shareholders they ostensibly work for. Two of the five major investment banks, Bear Stearns and Lehman, collapsed. The other three also would have gone under in the crisis, if not bailed out by the Fed and the Treasury. In addition, Citigroup and Bank of America, two of the four largest commercial banks, also would have faced collapse if not for massive government aid.

These Wall Street folks may be incredibly talented people in the same way that Bernie Madoff was, but if their talents benefit anyone other than themselves, they keep this fact well hidden.

Alec MacGillis had an interesting profile of Tom Nides in the New Yorker. Nides is currently a top executive at Morgan Stanley who is frequently mentioned as a leading contender for Treasury Secretary or other high level position in the Clinton administration. The piece ends with this remarkable section:

“But Barney Frank, the former Democratic congressman—who, despite having co-authored Dodd-Frank, is not opposed to former Wall Street executives working in Washington—told me that, in a friendly debate that he and Nides have conducted in recent years, Nides has vigorously defended Wall Street compensation: ‘He said, “These are extremely talented people who do valuable work.’”‘”

This one deserves a bit of thought. Remember, we’re talking about the top people at major banks, like former Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf. These people earns tens of millions of dollars a year. The folks at the hedge funds and private equity funds can earn hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

When we think about their talents, remember these are exactly the group of people that fueled the housing bubble with their fraudulent loans and bad securities. The country has paid and continues to pay an enormous price for this episode. If we look at the Congressional Budget Office’s estimates of potential GDP, its current estimate for 2016 is more than ten percent below its projection of 2016 potential GDP back in 2008, before the crash.

To get an idea of the magnitude of 10 percent of GDP, this is roughly 2.5 times the size of the Social Security tax. There are any number of people in Washington who would go absolutely nuts over the suggestion that we raise the Social Security tax by 2.0 percentage points (even if phased in over a decade). Imagine raising it by 30 percentage points. This would have the equivalent impact on people’s income as the long-term damage from the collapse of the housing bubble.

It is also worth noting that the Wall Street gang did not do even do well from the standpoint of the firms and shareholders they ostensibly work for. Two of the five major investment banks, Bear Stearns and Lehman, collapsed. The other three also would have gone under in the crisis, if not bailed out by the Fed and the Treasury. In addition, Citigroup and Bank of America, two of the four largest commercial banks, also would have faced collapse if not for massive government aid.

These Wall Street folks may be incredibly talented people in the same way that Bernie Madoff was, but if their talents benefit anyone other than themselves, they keep this fact well hidden.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s often said that economists are not very good at economics. (How else could they miss the $8 trillion housing bubble that sank the economy?) Anyhow, we are getting another case proving this point in the discussion of the acceleration of wage growth following the release of the October employment report.

While it does seem that there is a modest uptick in the rate of growth of the average hourly wage, this appears to be almost entirely due to the fact that we are seeing a shift from non-wage compensation (mostly health care) to wages. This was one of the goals of Obamacare, as it was hoped it would slow the growth of health care costs, leaving more money to go into workers’ paychecks.

This is still good news for workers (if the quality of their health care insurance is not deteriorating), but it is a substantially different story from one in which tighter labor markets are leading to a more rapid growth in compensation. In the latter case, there is at least an argument for the Fed to be concerned about the risk of inflation and to raise rates. However, it doesn’t make sense for the Fed to be thinking about raising interest rates and slowing job growth just because employers are shifting compensation from health care to wages.

Here’s the picture for the last five years. (The graph shows the annualized rate of change each quarter.)

I can’t see any acceleration in this picture. I guess that’s why I’m not at the Fed.

It’s often said that economists are not very good at economics. (How else could they miss the $8 trillion housing bubble that sank the economy?) Anyhow, we are getting another case proving this point in the discussion of the acceleration of wage growth following the release of the October employment report.

While it does seem that there is a modest uptick in the rate of growth of the average hourly wage, this appears to be almost entirely due to the fact that we are seeing a shift from non-wage compensation (mostly health care) to wages. This was one of the goals of Obamacare, as it was hoped it would slow the growth of health care costs, leaving more money to go into workers’ paychecks.

This is still good news for workers (if the quality of their health care insurance is not deteriorating), but it is a substantially different story from one in which tighter labor markets are leading to a more rapid growth in compensation. In the latter case, there is at least an argument for the Fed to be concerned about the risk of inflation and to raise rates. However, it doesn’t make sense for the Fed to be thinking about raising interest rates and slowing job growth just because employers are shifting compensation from health care to wages.

Here’s the picture for the last five years. (The graph shows the annualized rate of change each quarter.)

I can’t see any acceleration in this picture. I guess that’s why I’m not at the Fed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Carolyn Johnson has done a lot of excellent reporting on abuses and price gouging by the pharmaceutical industry, but her piece today on the “solution to the global crisis in drug prices” is more than a bit bizarre. I’ll save you the suspense. The solution is a “public benefit” company which is not set up to maximize profit. (I’m not sure what prevents it from being bought out by a standard profit maximizing company, but we’ll leave that one aside.)

While it is encouraging to hear some researchers actually interested in helping humanity rather than getting as rich as Bill Gates, this really seems like a major sidebar. There have been a long list of proposals of various types to have research funded in some form by the government, with all the findings placed in the public domain so that new drugs would be available at generic prices.

In this story, there is no need to rely on beneficent researchers. Researchers are paid for their work at the time they do it, just like billions of employees throughout the world. If it turns out poorly, that is unfortunate. Of course, incompetent researchers would be fired just like incompetent dishwashers and custodians. But if their work turned out to have huge health benefits, the public would enjoy them in the form of affordable drugs.

Publicly funded research also has the great benefit that research findings could be made public so that other researchers and doctors could benefit. This would allow research to advance more quickly and also for doctors to make more informed prescribing choices for their patients. (As it stands now, the industry only makes the results available that help it to market its drugs.)

Anyhow, it is remarkable that Johnson seems to be unaware of proposals for publicly funded research. (It can go through the private sector — it just doesn’t rely on patent monopolies.) The proponents are not an obscure group, they include Joe Stiglitz, a Nobel prize winning economist.

We already spend over $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health (NIH). While this money is primarily devoted to basic research, there is no obvious reason the funding couldn’t be doubled or tripled and designated to finance developing new drugs and carrying them through the FDA approval process. We spend over $430 billion a year on prescription drugs that would sell for 10–20 percent of this price in a free market, so there is plenty of room to increase funding and still end up way ahead.

While the industry pushes the line that the NIH or equivalent agency would turn into bumbling idiots if they allocated money for drug development, it argues that the current funding is money very well spent and consistently argues for more. Perhaps Johnson shares the industry’s bizarre theory of knowledge, otherwise it is difficult to understand why she would not be looking at this obvious solution for high drug prices.

Carolyn Johnson has done a lot of excellent reporting on abuses and price gouging by the pharmaceutical industry, but her piece today on the “solution to the global crisis in drug prices” is more than a bit bizarre. I’ll save you the suspense. The solution is a “public benefit” company which is not set up to maximize profit. (I’m not sure what prevents it from being bought out by a standard profit maximizing company, but we’ll leave that one aside.)

While it is encouraging to hear some researchers actually interested in helping humanity rather than getting as rich as Bill Gates, this really seems like a major sidebar. There have been a long list of proposals of various types to have research funded in some form by the government, with all the findings placed in the public domain so that new drugs would be available at generic prices.

In this story, there is no need to rely on beneficent researchers. Researchers are paid for their work at the time they do it, just like billions of employees throughout the world. If it turns out poorly, that is unfortunate. Of course, incompetent researchers would be fired just like incompetent dishwashers and custodians. But if their work turned out to have huge health benefits, the public would enjoy them in the form of affordable drugs.

Publicly funded research also has the great benefit that research findings could be made public so that other researchers and doctors could benefit. This would allow research to advance more quickly and also for doctors to make more informed prescribing choices for their patients. (As it stands now, the industry only makes the results available that help it to market its drugs.)

Anyhow, it is remarkable that Johnson seems to be unaware of proposals for publicly funded research. (It can go through the private sector — it just doesn’t rely on patent monopolies.) The proponents are not an obscure group, they include Joe Stiglitz, a Nobel prize winning economist.

We already spend over $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health (NIH). While this money is primarily devoted to basic research, there is no obvious reason the funding couldn’t be doubled or tripled and designated to finance developing new drugs and carrying them through the FDA approval process. We spend over $430 billion a year on prescription drugs that would sell for 10–20 percent of this price in a free market, so there is plenty of room to increase funding and still end up way ahead.

While the industry pushes the line that the NIH or equivalent agency would turn into bumbling idiots if they allocated money for drug development, it argues that the current funding is money very well spent and consistently argues for more. Perhaps Johnson shares the industry’s bizarre theory of knowledge, otherwise it is difficult to understand why she would not be looking at this obvious solution for high drug prices.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Thomas Edsall’s NYT column contrasted the downscale white working class Trump supporters with the growing number of college educated and relatively upscale supporters of Democrats. Near the end of the piece, Edsall quotes M.I.T. economist Daron Acemoglu:

“As long as the Democratic Party shakes off its hard-core anti-market, pro-union stance, there is a huge constituency of well-educated, socially conscious Americans that will join in.”

Rather than completely abandon its base in the working class (of all races) there is an alternative route for the Democrats, they could abandon their hard core anti-market positions that benefit the wealthy.

This could start with abandoning their position, especially in trade deals, to make government granted patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger. These anti-market interventions are affecting an ever larger share of the economy (in prescription drugs alone patent related protections likely increase the costs by more than $350 billion annually). They directly redistribute income from ordinary workers to the relatively wealthy minority in a position to earn rents from these forms of protectionism.

The Democrats can also abandon the licensing restrictions that protect doctors, dentists, and other highly paid professionals from both domestic and international competition. Our laws prevent doctors from practicing medicine unless they complete a U.S. residency program. This is about as blatant a protectionist barrier as you’ll find these days. It allows doctors in the United States to earn on average more than $250,000 a year, twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries like Germany and Canada. This protectionism costs us around $100 billion a year in higher medical costs.

We could also subject the financial sector to the same sort of taxes as other sectors of the economy pay (e.g. a financial transactions tax). This market based reform could eliminate more than $100 billion a year in waste in the financial sector that ends up as income for bankers and hedge fund types.

There is a long list of market-friendly measures that would help to reverse the upward redistribution of the last four decades. (Yep, this is the topic of my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.) Anyhow, supporters of this upward redistribution do their best to turn language on its head and deny that these forms of protectionism are protection. They pretend that patent and copyright protections are the free market or that they never heard of restrictions on foreign doctors. Unfortunately, this group of deniers includes most of the people who write on these issues. But, there is always hope that they can learn.

Note: Typos in an earlier version were corrected, thanks Robert Salzberg.

Thomas Edsall’s NYT column contrasted the downscale white working class Trump supporters with the growing number of college educated and relatively upscale supporters of Democrats. Near the end of the piece, Edsall quotes M.I.T. economist Daron Acemoglu:

“As long as the Democratic Party shakes off its hard-core anti-market, pro-union stance, there is a huge constituency of well-educated, socially conscious Americans that will join in.”

Rather than completely abandon its base in the working class (of all races) there is an alternative route for the Democrats, they could abandon their hard core anti-market positions that benefit the wealthy.

This could start with abandoning their position, especially in trade deals, to make government granted patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger. These anti-market interventions are affecting an ever larger share of the economy (in prescription drugs alone patent related protections likely increase the costs by more than $350 billion annually). They directly redistribute income from ordinary workers to the relatively wealthy minority in a position to earn rents from these forms of protectionism.

The Democrats can also abandon the licensing restrictions that protect doctors, dentists, and other highly paid professionals from both domestic and international competition. Our laws prevent doctors from practicing medicine unless they complete a U.S. residency program. This is about as blatant a protectionist barrier as you’ll find these days. It allows doctors in the United States to earn on average more than $250,000 a year, twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries like Germany and Canada. This protectionism costs us around $100 billion a year in higher medical costs.

We could also subject the financial sector to the same sort of taxes as other sectors of the economy pay (e.g. a financial transactions tax). This market based reform could eliminate more than $100 billion a year in waste in the financial sector that ends up as income for bankers and hedge fund types.

There is a long list of market-friendly measures that would help to reverse the upward redistribution of the last four decades. (Yep, this is the topic of my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.) Anyhow, supporters of this upward redistribution do their best to turn language on its head and deny that these forms of protectionism are protection. They pretend that patent and copyright protections are the free market or that they never heard of restrictions on foreign doctors. Unfortunately, this group of deniers includes most of the people who write on these issues. But, there is always hope that they can learn.

Note: Typos in an earlier version were corrected, thanks Robert Salzberg.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

by Dean Baker and Lara Merling

It’s no secret that many folks, including many on the Fed, want to see higher interest rates. There are a variety of arguments put forward, including the story of huge but invisible bubbles that could burst and sink the economy just like the housing bubble did in 2008.

But the argument that deserves the most credibility is the conventional one that a low rate of unemployment is creating an overtight labor market. This leads to more wage growth, which will get passed along in more rapid inflation, which will soon force the Fed’s hand. At some point the Fed will have to raise rates to keep inflation from getting out of control or we will be back in an era of excessive inflation. By this logic it is better to get out front and do it now.

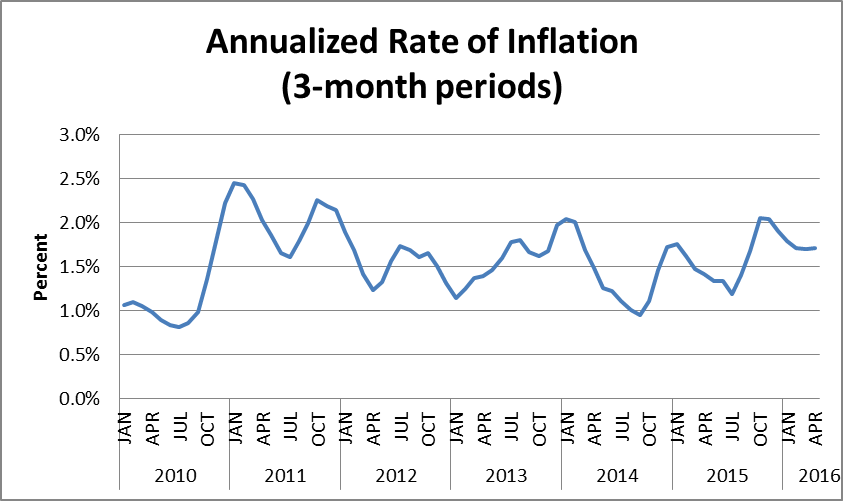

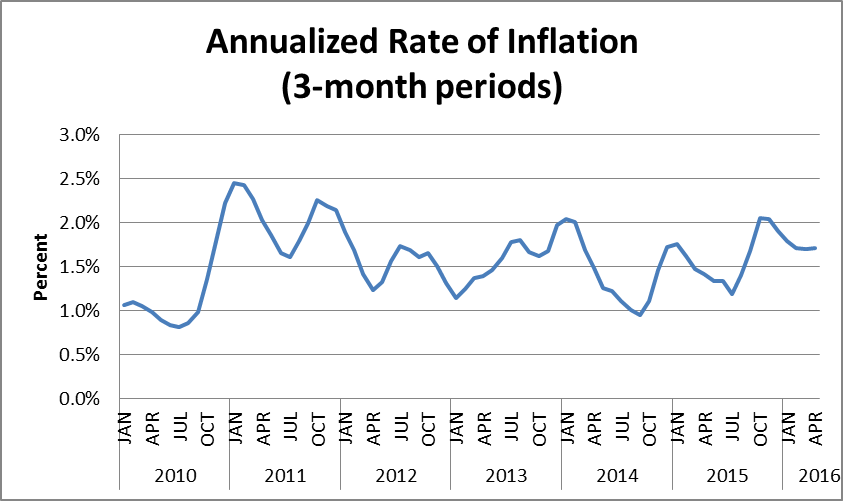

In this story, we should at least be seeing the beginnings of an acceleration of inflation, but we don’t. The figure below shows the core personal consumption expenditure deflator which provides the basis for the Fed’s 2.0 percent (average) inflation target.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The figure shows the annualized rate of inflation using average price levels from the most recent three-month period compared with average price levels from the prior three month period. It’s pretty hard to see any evidence of an upward trend in these data. The core rate had approached 2.5 percent in early 2011. It had minor fluctuations, but eventually bottomed out at 1.0 percent in the fall of 2014. It has moved modestly higher in the last two years, peaking at 2.0 percent at the end of 2015, but since then has crept down to 1.7 percent.

Of course, it is always possible that we will see the picture change and inflation will suddenly start to accelerate, but the point is that it has not yet done so. Furthermore, none of the standard models show that inflation suddenly jumps upward. If it does start to increase it would likely be a long and gradual process. For this reason, it is difficult to see the urgency in the drive to raise interest rates.

by Dean Baker and Lara Merling

It’s no secret that many folks, including many on the Fed, want to see higher interest rates. There are a variety of arguments put forward, including the story of huge but invisible bubbles that could burst and sink the economy just like the housing bubble did in 2008.

But the argument that deserves the most credibility is the conventional one that a low rate of unemployment is creating an overtight labor market. This leads to more wage growth, which will get passed along in more rapid inflation, which will soon force the Fed’s hand. At some point the Fed will have to raise rates to keep inflation from getting out of control or we will be back in an era of excessive inflation. By this logic it is better to get out front and do it now.

In this story, we should at least be seeing the beginnings of an acceleration of inflation, but we don’t. The figure below shows the core personal consumption expenditure deflator which provides the basis for the Fed’s 2.0 percent (average) inflation target.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The figure shows the annualized rate of inflation using average price levels from the most recent three-month period compared with average price levels from the prior three month period. It’s pretty hard to see any evidence of an upward trend in these data. The core rate had approached 2.5 percent in early 2011. It had minor fluctuations, but eventually bottomed out at 1.0 percent in the fall of 2014. It has moved modestly higher in the last two years, peaking at 2.0 percent at the end of 2015, but since then has crept down to 1.7 percent.

Of course, it is always possible that we will see the picture change and inflation will suddenly start to accelerate, but the point is that it has not yet done so. Furthermore, none of the standard models show that inflation suddenly jumps upward. If it does start to increase it would likely be a long and gradual process. For this reason, it is difficult to see the urgency in the drive to raise interest rates.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting article arguing that trade has stopped growing in the last couple of years. The piece notes data showing that combined U.S. exports and imports fell in the 2015 compared to 2014 and seem likely to fall again in 2016. It then raises the concern that this will lead to slower growth going forward. There are a couple of points that complicate this issue.

The first is that the drop in the dollar value of trade is the result of lower prices, not a smaller volume of goods and services being imported and exported. While the nominal value of exports fell by $111.0 billion from 2014 to 2015, the real value actually rose by $2.3 billion. On the import side, the nominal value fell by $97.8 billion while the real value rose by $116.5 billion.

In other words, the actual amount of goods and services crossing U.S. borders in 2015 was in fact higher in 2015 than in 2014, we were just paying less for what we imported and foreigners were paying less for what we exported to them. The big factors here were the sharp drop in oil prices and comparable drops in the price of many agricultural commodities that we export. It is not clear that this is bad for economic growth, but in any case the issue is not a drop in the quantity of goods and services crossing national borders.

The other point is that the definition of a traded item can change depending on the property rules in place at the time. To take a simple example, suppose that one billion people in China use Microsoft’s Windows operating system. If we make them all pay $50 for each system then this is $50 billion in U.S. exports to China. Now suppose that everyone in China is able to use Windows at no cost. In this case we have $50 billion less in exports, but we still have one billion people in China getting the benefit of the Windows operating system.

Much of the focus of U.S. trade policy in recent decades has been about making other countries pay for items that in principle could be free through patents and copyright protection. (Yes, this is protectionism, even if your friends profit from it.) It is not clear that we are boosting world growth by making countries pay more money for items like prescription drugs, software, recorded music and video material, although we would certainly be increasing the dollar value of trade flows.

The long and short is that it is not clear what we are measuring when we see a decline in trading or volume or what it would mean if trading volume increases because we can force other countries to pay for items that would otherwise be available for free. (Yes, these issues are covered in my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer, which is available for free.)

The NYT had an interesting article arguing that trade has stopped growing in the last couple of years. The piece notes data showing that combined U.S. exports and imports fell in the 2015 compared to 2014 and seem likely to fall again in 2016. It then raises the concern that this will lead to slower growth going forward. There are a couple of points that complicate this issue.

The first is that the drop in the dollar value of trade is the result of lower prices, not a smaller volume of goods and services being imported and exported. While the nominal value of exports fell by $111.0 billion from 2014 to 2015, the real value actually rose by $2.3 billion. On the import side, the nominal value fell by $97.8 billion while the real value rose by $116.5 billion.

In other words, the actual amount of goods and services crossing U.S. borders in 2015 was in fact higher in 2015 than in 2014, we were just paying less for what we imported and foreigners were paying less for what we exported to them. The big factors here were the sharp drop in oil prices and comparable drops in the price of many agricultural commodities that we export. It is not clear that this is bad for economic growth, but in any case the issue is not a drop in the quantity of goods and services crossing national borders.

The other point is that the definition of a traded item can change depending on the property rules in place at the time. To take a simple example, suppose that one billion people in China use Microsoft’s Windows operating system. If we make them all pay $50 for each system then this is $50 billion in U.S. exports to China. Now suppose that everyone in China is able to use Windows at no cost. In this case we have $50 billion less in exports, but we still have one billion people in China getting the benefit of the Windows operating system.

Much of the focus of U.S. trade policy in recent decades has been about making other countries pay for items that in principle could be free through patents and copyright protection. (Yes, this is protectionism, even if your friends profit from it.) It is not clear that we are boosting world growth by making countries pay more money for items like prescription drugs, software, recorded music and video material, although we would certainly be increasing the dollar value of trade flows.

The long and short is that it is not clear what we are measuring when we see a decline in trading or volume or what it would mean if trading volume increases because we can force other countries to pay for items that would otherwise be available for free. (Yes, these issues are covered in my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer, which is available for free.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión