One of the great myths perpetuated by the right is that Dodd-Frank and other financial regulations by the Obama administration are preventing the financial sector from functioning. As a result, small businesses supposedly can’t get the credit they need to grow or even survive. University of Maryland economist Peter Morici made this argument in a Morning Edition segment in a debate with my friend Jared Bernstein.

There is actually a simple response to this claim: it’s not true. The National Federation of Independent Businesses has been conducting a monthly survey of small businesses for more than thirty years. One of questions it poses is about credit conditions. In the most recent survey only 2 percent reported that financing was their top business problem. This is near a low point for the survey’s history. In other words, if small businesses are having serious problems getting credit, someone forget to tell them.

One of the great myths perpetuated by the right is that Dodd-Frank and other financial regulations by the Obama administration are preventing the financial sector from functioning. As a result, small businesses supposedly can’t get the credit they need to grow or even survive. University of Maryland economist Peter Morici made this argument in a Morning Edition segment in a debate with my friend Jared Bernstein.

There is actually a simple response to this claim: it’s not true. The National Federation of Independent Businesses has been conducting a monthly survey of small businesses for more than thirty years. One of questions it poses is about credit conditions. In the most recent survey only 2 percent reported that financing was their top business problem. This is near a low point for the survey’s history. In other words, if small businesses are having serious problems getting credit, someone forget to tell them.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting piece that focused on the Carrier air conditioner factory in Indianapolis, Indiana that the company is closing and moving to Mexico. The piece describes the impact on the city and the people who work in the factory, many of whom apparently voted for Donald Trump in the hope that he would save their jobs.

One item in the story is somewhat misleading. The piece presents the views of John Van Reenen, an economist at M.I.T.:

“‘These are fundamental forces that have more to do with technology than trade.’

In particular, he said, across developed economies more national income is going to capital, that is, owners and shareholders, rather than labor. ‘We’ve seen this in many countries with different political systems,’ he said. ‘It’s a winner-take-all world.'”

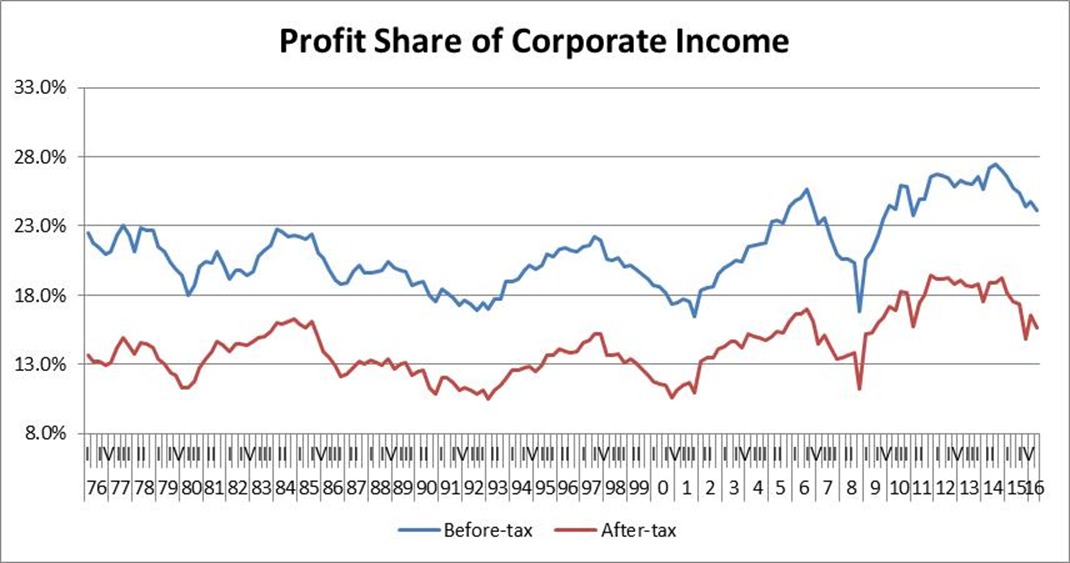

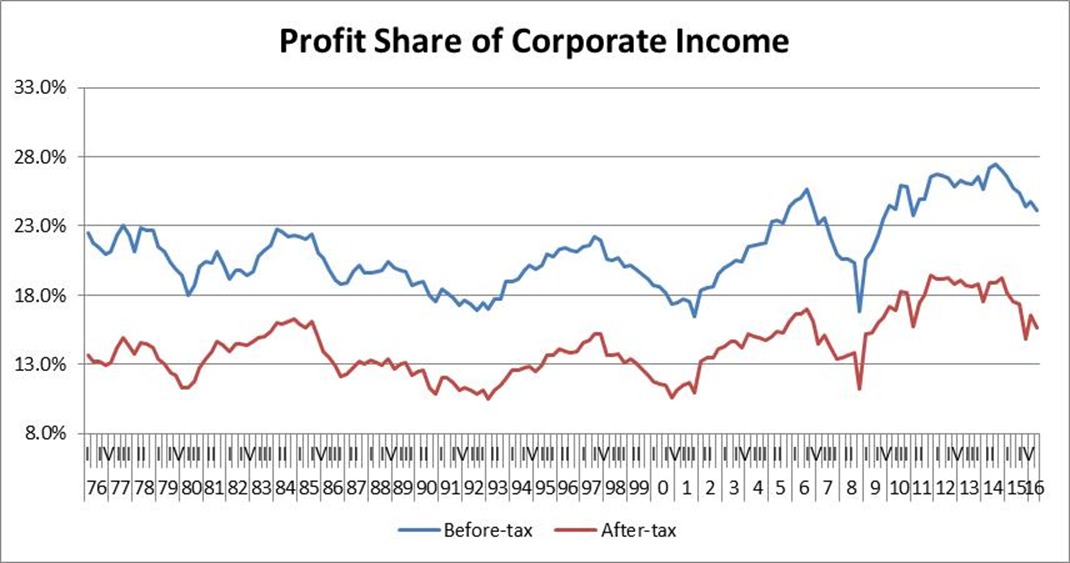

There are two important qualifications that should be made to these comments. First, while there was a substantial shift of income from labor to capital in most wealthy countries in the the last four decades, that was not really the case in the United States. While there were cyclical ups and downs, there was little change in the capital share of corporate income until 2005, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

This is worth noting since the bulk of the upward redistribution had already been accomplished by 2005. The implication is that the upward redistribution was not due to firms getting more profits are the expense of workers in general, but rather higher paid workers benefiting at the expense of less-highly paid workers.

In the context of the trade story discussed here, this means that the lower cost of labor from outsourcing jobs to other countries was largely passed on to consumers in lower prices. While the workers who lost jobs and/or were forced to take pay cuts are hurt in this story (essentially the portion of the work force without college degrees), high end workers like CEOs and Wall Street types benefit. Also professionals like doctors, who benefit from protectionist restrictions (foreign doctors are prohibited from practicing in the United States unless they complete a U.S. residency program), benefit as well. This policy of selective protectionism had the predicted and actual effect of redistributing income upward.

The shift of income to profits since 2005 is likely in large part a result of the weakness in the labor market following the collapse of the housing bubble and the resulting recession. It appears that the labor share is again recovering, but whether it actually gets back to its pre-recession (and pre-2005) level will depend in large part on whether the labor market is allowed to tighten further or the Fed prevents further tightening by hiking interest rates.

The other qualification to Van Reenen’s comments is that technology does not by itself determine distribution. The claims to ownership of technology (i.e. patent protection, copyright protection, and related forms of intellectual property claims) are what determine distribution. In the past four decades, Congress has implemented numerous measures both nationally and internationally through trade agreements that had the explicit purpose of making these protections stronger and longer. So the resulting upward redistribution cannot be attributed simply to “technology,” rather it was the result of policy decisions that were intended for this purpose.

The NYT had an interesting piece that focused on the Carrier air conditioner factory in Indianapolis, Indiana that the company is closing and moving to Mexico. The piece describes the impact on the city and the people who work in the factory, many of whom apparently voted for Donald Trump in the hope that he would save their jobs.

One item in the story is somewhat misleading. The piece presents the views of John Van Reenen, an economist at M.I.T.:

“‘These are fundamental forces that have more to do with technology than trade.’

In particular, he said, across developed economies more national income is going to capital, that is, owners and shareholders, rather than labor. ‘We’ve seen this in many countries with different political systems,’ he said. ‘It’s a winner-take-all world.'”

There are two important qualifications that should be made to these comments. First, while there was a substantial shift of income from labor to capital in most wealthy countries in the the last four decades, that was not really the case in the United States. While there were cyclical ups and downs, there was little change in the capital share of corporate income until 2005, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

This is worth noting since the bulk of the upward redistribution had already been accomplished by 2005. The implication is that the upward redistribution was not due to firms getting more profits are the expense of workers in general, but rather higher paid workers benefiting at the expense of less-highly paid workers.

In the context of the trade story discussed here, this means that the lower cost of labor from outsourcing jobs to other countries was largely passed on to consumers in lower prices. While the workers who lost jobs and/or were forced to take pay cuts are hurt in this story (essentially the portion of the work force without college degrees), high end workers like CEOs and Wall Street types benefit. Also professionals like doctors, who benefit from protectionist restrictions (foreign doctors are prohibited from practicing in the United States unless they complete a U.S. residency program), benefit as well. This policy of selective protectionism had the predicted and actual effect of redistributing income upward.

The shift of income to profits since 2005 is likely in large part a result of the weakness in the labor market following the collapse of the housing bubble and the resulting recession. It appears that the labor share is again recovering, but whether it actually gets back to its pre-recession (and pre-2005) level will depend in large part on whether the labor market is allowed to tighten further or the Fed prevents further tightening by hiking interest rates.

The other qualification to Van Reenen’s comments is that technology does not by itself determine distribution. The claims to ownership of technology (i.e. patent protection, copyright protection, and related forms of intellectual property claims) are what determine distribution. In the past four decades, Congress has implemented numerous measures both nationally and internationally through trade agreements that had the explicit purpose of making these protections stronger and longer. So the resulting upward redistribution cannot be attributed simply to “technology,” rather it was the result of policy decisions that were intended for this purpose.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a piece with the headline, “Trump rides a wave of populist fury that may damage global prosperity.” The headline is absolutely bizarre for the simple reason that we are not seeing anything that a serious person can call “global prosperity.” Thanks to the austerity policies pursued across much of the across Europe, and to a lesser extent the United States, countries across the developing world have seen a decade of weak or even negative growth. The employment rate of prime age workers (ages 25-54) is still below its pre-recession level in many countries, including in the United States.

These points are actually a major point of the article itself, which emphasizes the poor performance of most economies as a trigger for populist sentiment. In this respect the headline effectively contradicts the point of the article. While the populist policies being advocated by politicians may not offer a good answer for economic problems, we do not have to worry that they somehow will ruin an economic golden age. The mainstream leaders designing economic policy already destroyed prosperity, which doesn’t mean that some ill-designed populist policies couldn’t make things worse.

One point where the article is mistaken is in dismissing the idea that some people in the UK might be benefited by Brexit.

“In northeastern England (something like the Rust Belt of Britain) people who voted to leave Europe speak openly about doing so to punish those who beseeched them to vote to stay — people like the exceedingly unpopular former prime minister David Cameron. The situation is so depressed, it cannot get worse, the logic runs. Any economic pain will fall on wealthy Londoners, people say.

“But that is almost certainly nonsense. A rupture of trade with Europe is likely to hit these industrial communities hardest. And if that happens, the people living there will be angrier than ever.”

Actually there is a very plausible story under which Brexit may benefit left behind industrial communities, which comes directly out of standard economics. Brexit is likely to first and foremost hit the London financial center by denying it privileged access to the EU. This will lead to less exports of financial services, which lower the value of the pound, other things equal. That makes the goods produced by industry in the UK more competitive, increasing output and employment.

This is largely consistent with what we have seen in the months since the vote for Brexit. The pound has plunged against both the euro and the dollar. Also, we have seen a sharp decline in London real estate prices, while house prices have risen in the rest of the country.

While Brexit may not have been an ideal tool for the purpose (policy is never textbook ideal), it may actually provide an effective way to divert resources from the financial sector to the rest of the UK economy. It is certainly too early to pronounce the policy successful in this respect, but it is also too early to insist that it is a failure.

The NYT ran a piece with the headline, “Trump rides a wave of populist fury that may damage global prosperity.” The headline is absolutely bizarre for the simple reason that we are not seeing anything that a serious person can call “global prosperity.” Thanks to the austerity policies pursued across much of the across Europe, and to a lesser extent the United States, countries across the developing world have seen a decade of weak or even negative growth. The employment rate of prime age workers (ages 25-54) is still below its pre-recession level in many countries, including in the United States.

These points are actually a major point of the article itself, which emphasizes the poor performance of most economies as a trigger for populist sentiment. In this respect the headline effectively contradicts the point of the article. While the populist policies being advocated by politicians may not offer a good answer for economic problems, we do not have to worry that they somehow will ruin an economic golden age. The mainstream leaders designing economic policy already destroyed prosperity, which doesn’t mean that some ill-designed populist policies couldn’t make things worse.

One point where the article is mistaken is in dismissing the idea that some people in the UK might be benefited by Brexit.

“In northeastern England (something like the Rust Belt of Britain) people who voted to leave Europe speak openly about doing so to punish those who beseeched them to vote to stay — people like the exceedingly unpopular former prime minister David Cameron. The situation is so depressed, it cannot get worse, the logic runs. Any economic pain will fall on wealthy Londoners, people say.

“But that is almost certainly nonsense. A rupture of trade with Europe is likely to hit these industrial communities hardest. And if that happens, the people living there will be angrier than ever.”

Actually there is a very plausible story under which Brexit may benefit left behind industrial communities, which comes directly out of standard economics. Brexit is likely to first and foremost hit the London financial center by denying it privileged access to the EU. This will lead to less exports of financial services, which lower the value of the pound, other things equal. That makes the goods produced by industry in the UK more competitive, increasing output and employment.

This is largely consistent with what we have seen in the months since the vote for Brexit. The pound has plunged against both the euro and the dollar. Also, we have seen a sharp decline in London real estate prices, while house prices have risen in the rest of the country.

While Brexit may not have been an ideal tool for the purpose (policy is never textbook ideal), it may actually provide an effective way to divert resources from the financial sector to the rest of the UK economy. It is certainly too early to pronounce the policy successful in this respect, but it is also too early to insist that it is a failure.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Alec MacGillis had an interesting profile of Tom Nides in the New Yorker. Nides is currently a top executive at Morgan Stanley who is frequently mentioned as a leading contender for Treasury Secretary or other high level position in the Clinton administration. The piece ends with this remarkable section:

“But Barney Frank, the former Democratic congressman—who, despite having co-authored Dodd-Frank, is not opposed to former Wall Street executives working in Washington—told me that, in a friendly debate that he and Nides have conducted in recent years, Nides has vigorously defended Wall Street compensation: ‘He said, “These are extremely talented people who do valuable work.’”‘”

This one deserves a bit of thought. Remember, we’re talking about the top people at major banks, like former Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf. These people earns tens of millions of dollars a year. The folks at the hedge funds and private equity funds can earn hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

When we think about their talents, remember these are exactly the group of people that fueled the housing bubble with their fraudulent loans and bad securities. The country has paid and continues to pay an enormous price for this episode. If we look at the Congressional Budget Office’s estimates of potential GDP, its current estimate for 2016 is more than ten percent below its projection of 2016 potential GDP back in 2008, before the crash.

To get an idea of the magnitude of 10 percent of GDP, this is roughly 2.5 times the size of the Social Security tax. There are any number of people in Washington who would go absolutely nuts over the suggestion that we raise the Social Security tax by 2.0 percentage points (even if phased in over a decade). Imagine raising it by 30 percentage points. This would have the equivalent impact on people’s income as the long-term damage from the collapse of the housing bubble.

It is also worth noting that the Wall Street gang did not do even do well from the standpoint of the firms and shareholders they ostensibly work for. Two of the five major investment banks, Bear Stearns and Lehman, collapsed. The other three also would have gone under in the crisis, if not bailed out by the Fed and the Treasury. In addition, Citigroup and Bank of America, two of the four largest commercial banks, also would have faced collapse if not for massive government aid.

These Wall Street folks may be incredibly talented people in the same way that Bernie Madoff was, but if their talents benefit anyone other than themselves, they keep this fact well hidden.

Alec MacGillis had an interesting profile of Tom Nides in the New Yorker. Nides is currently a top executive at Morgan Stanley who is frequently mentioned as a leading contender for Treasury Secretary or other high level position in the Clinton administration. The piece ends with this remarkable section:

“But Barney Frank, the former Democratic congressman—who, despite having co-authored Dodd-Frank, is not opposed to former Wall Street executives working in Washington—told me that, in a friendly debate that he and Nides have conducted in recent years, Nides has vigorously defended Wall Street compensation: ‘He said, “These are extremely talented people who do valuable work.’”‘”

This one deserves a bit of thought. Remember, we’re talking about the top people at major banks, like former Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf. These people earns tens of millions of dollars a year. The folks at the hedge funds and private equity funds can earn hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

When we think about their talents, remember these are exactly the group of people that fueled the housing bubble with their fraudulent loans and bad securities. The country has paid and continues to pay an enormous price for this episode. If we look at the Congressional Budget Office’s estimates of potential GDP, its current estimate for 2016 is more than ten percent below its projection of 2016 potential GDP back in 2008, before the crash.

To get an idea of the magnitude of 10 percent of GDP, this is roughly 2.5 times the size of the Social Security tax. There are any number of people in Washington who would go absolutely nuts over the suggestion that we raise the Social Security tax by 2.0 percentage points (even if phased in over a decade). Imagine raising it by 30 percentage points. This would have the equivalent impact on people’s income as the long-term damage from the collapse of the housing bubble.

It is also worth noting that the Wall Street gang did not do even do well from the standpoint of the firms and shareholders they ostensibly work for. Two of the five major investment banks, Bear Stearns and Lehman, collapsed. The other three also would have gone under in the crisis, if not bailed out by the Fed and the Treasury. In addition, Citigroup and Bank of America, two of the four largest commercial banks, also would have faced collapse if not for massive government aid.

These Wall Street folks may be incredibly talented people in the same way that Bernie Madoff was, but if their talents benefit anyone other than themselves, they keep this fact well hidden.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s often said that economists are not very good at economics. (How else could they miss the $8 trillion housing bubble that sank the economy?) Anyhow, we are getting another case proving this point in the discussion of the acceleration of wage growth following the release of the October employment report.

While it does seem that there is a modest uptick in the rate of growth of the average hourly wage, this appears to be almost entirely due to the fact that we are seeing a shift from non-wage compensation (mostly health care) to wages. This was one of the goals of Obamacare, as it was hoped it would slow the growth of health care costs, leaving more money to go into workers’ paychecks.

This is still good news for workers (if the quality of their health care insurance is not deteriorating), but it is a substantially different story from one in which tighter labor markets are leading to a more rapid growth in compensation. In the latter case, there is at least an argument for the Fed to be concerned about the risk of inflation and to raise rates. However, it doesn’t make sense for the Fed to be thinking about raising interest rates and slowing job growth just because employers are shifting compensation from health care to wages.

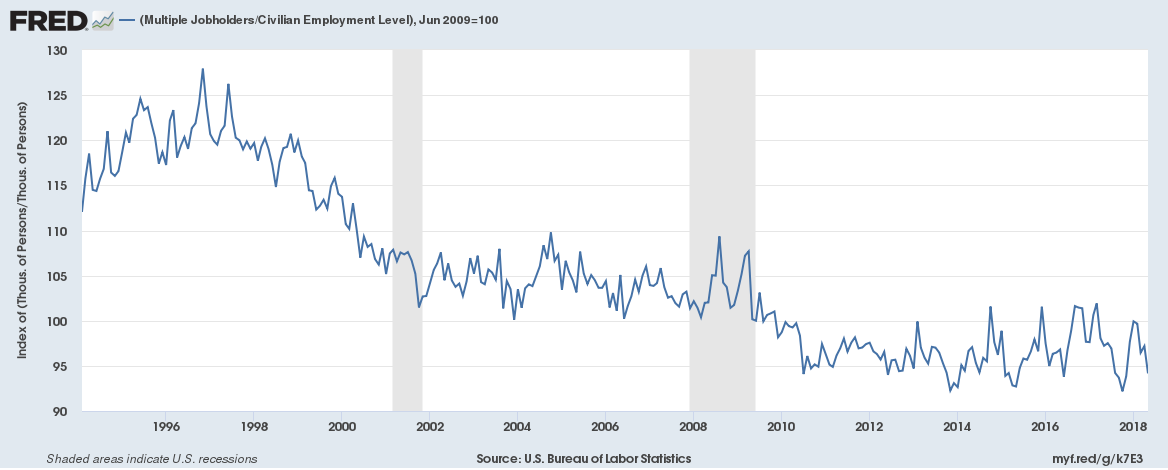

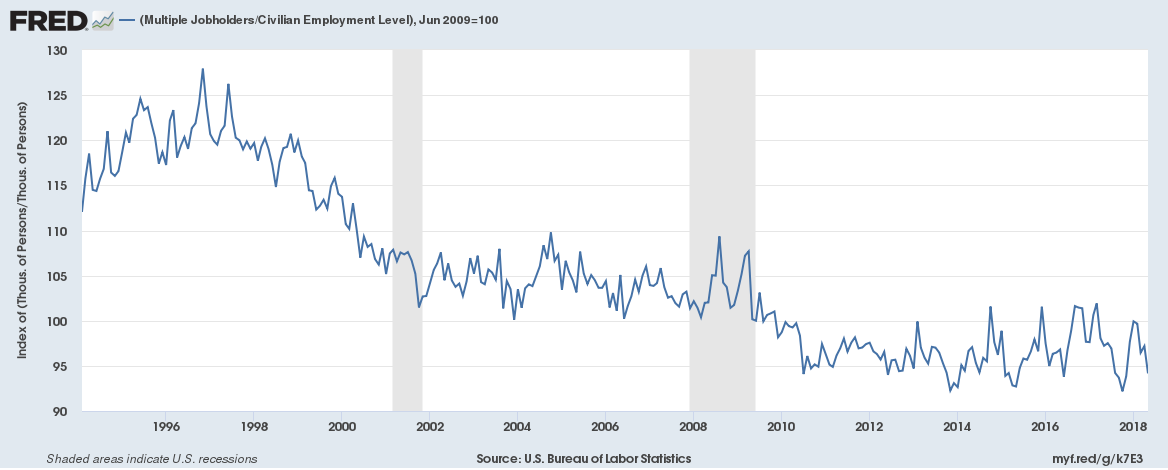

Here’s the picture for the last five years. (The graph shows the annualized rate of change each quarter.)

I can’t see any acceleration in this picture. I guess that’s why I’m not at the Fed.

It’s often said that economists are not very good at economics. (How else could they miss the $8 trillion housing bubble that sank the economy?) Anyhow, we are getting another case proving this point in the discussion of the acceleration of wage growth following the release of the October employment report.

While it does seem that there is a modest uptick in the rate of growth of the average hourly wage, this appears to be almost entirely due to the fact that we are seeing a shift from non-wage compensation (mostly health care) to wages. This was one of the goals of Obamacare, as it was hoped it would slow the growth of health care costs, leaving more money to go into workers’ paychecks.

This is still good news for workers (if the quality of their health care insurance is not deteriorating), but it is a substantially different story from one in which tighter labor markets are leading to a more rapid growth in compensation. In the latter case, there is at least an argument for the Fed to be concerned about the risk of inflation and to raise rates. However, it doesn’t make sense for the Fed to be thinking about raising interest rates and slowing job growth just because employers are shifting compensation from health care to wages.

Here’s the picture for the last five years. (The graph shows the annualized rate of change each quarter.)

I can’t see any acceleration in this picture. I guess that’s why I’m not at the Fed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Carolyn Johnson has done a lot of excellent reporting on abuses and price gouging by the pharmaceutical industry, but her piece today on the “solution to the global crisis in drug prices” is more than a bit bizarre. I’ll save you the suspense. The solution is a “public benefit” company which is not set up to maximize profit. (I’m not sure what prevents it from being bought out by a standard profit maximizing company, but we’ll leave that one aside.)

While it is encouraging to hear some researchers actually interested in helping humanity rather than getting as rich as Bill Gates, this really seems like a major sidebar. There have been a long list of proposals of various types to have research funded in some form by the government, with all the findings placed in the public domain so that new drugs would be available at generic prices.

In this story, there is no need to rely on beneficent researchers. Researchers are paid for their work at the time they do it, just like billions of employees throughout the world. If it turns out poorly, that is unfortunate. Of course, incompetent researchers would be fired just like incompetent dishwashers and custodians. But if their work turned out to have huge health benefits, the public would enjoy them in the form of affordable drugs.

Publicly funded research also has the great benefit that research findings could be made public so that other researchers and doctors could benefit. This would allow research to advance more quickly and also for doctors to make more informed prescribing choices for their patients. (As it stands now, the industry only makes the results available that help it to market its drugs.)

Anyhow, it is remarkable that Johnson seems to be unaware of proposals for publicly funded research. (It can go through the private sector — it just doesn’t rely on patent monopolies.) The proponents are not an obscure group, they include Joe Stiglitz, a Nobel prize winning economist.

We already spend over $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health (NIH). While this money is primarily devoted to basic research, there is no obvious reason the funding couldn’t be doubled or tripled and designated to finance developing new drugs and carrying them through the FDA approval process. We spend over $430 billion a year on prescription drugs that would sell for 10–20 percent of this price in a free market, so there is plenty of room to increase funding and still end up way ahead.

While the industry pushes the line that the NIH or equivalent agency would turn into bumbling idiots if they allocated money for drug development, it argues that the current funding is money very well spent and consistently argues for more. Perhaps Johnson shares the industry’s bizarre theory of knowledge, otherwise it is difficult to understand why she would not be looking at this obvious solution for high drug prices.

Carolyn Johnson has done a lot of excellent reporting on abuses and price gouging by the pharmaceutical industry, but her piece today on the “solution to the global crisis in drug prices” is more than a bit bizarre. I’ll save you the suspense. The solution is a “public benefit” company which is not set up to maximize profit. (I’m not sure what prevents it from being bought out by a standard profit maximizing company, but we’ll leave that one aside.)

While it is encouraging to hear some researchers actually interested in helping humanity rather than getting as rich as Bill Gates, this really seems like a major sidebar. There have been a long list of proposals of various types to have research funded in some form by the government, with all the findings placed in the public domain so that new drugs would be available at generic prices.

In this story, there is no need to rely on beneficent researchers. Researchers are paid for their work at the time they do it, just like billions of employees throughout the world. If it turns out poorly, that is unfortunate. Of course, incompetent researchers would be fired just like incompetent dishwashers and custodians. But if their work turned out to have huge health benefits, the public would enjoy them in the form of affordable drugs.

Publicly funded research also has the great benefit that research findings could be made public so that other researchers and doctors could benefit. This would allow research to advance more quickly and also for doctors to make more informed prescribing choices for their patients. (As it stands now, the industry only makes the results available that help it to market its drugs.)

Anyhow, it is remarkable that Johnson seems to be unaware of proposals for publicly funded research. (It can go through the private sector — it just doesn’t rely on patent monopolies.) The proponents are not an obscure group, they include Joe Stiglitz, a Nobel prize winning economist.

We already spend over $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health (NIH). While this money is primarily devoted to basic research, there is no obvious reason the funding couldn’t be doubled or tripled and designated to finance developing new drugs and carrying them through the FDA approval process. We spend over $430 billion a year on prescription drugs that would sell for 10–20 percent of this price in a free market, so there is plenty of room to increase funding and still end up way ahead.

While the industry pushes the line that the NIH or equivalent agency would turn into bumbling idiots if they allocated money for drug development, it argues that the current funding is money very well spent and consistently argues for more. Perhaps Johnson shares the industry’s bizarre theory of knowledge, otherwise it is difficult to understand why she would not be looking at this obvious solution for high drug prices.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión