The Social Security scare story is a long established Washington ritual. Bloomberg news decided to bring it out again in time for Halloween. The basic story is that the Social Security trust fund is projected to face a shortfall in less than two decades. This means that unless Congress appropriates additional revenue, the program is projected to only be able to pay a bit more than 80 percent of scheduled benefits.

This much is not really in dispute. The question is how much should we be worried about this projected shortfall and what should we do about it. Bloomberg’s answer to the first question is that we should be very worried. It goes through the list of potential fixes and implies that all would be difficult or impossible.

I will just take one potential fix, which is raising the payroll tax by 2.58 percentage points to cover the projected shortfall. Bloomberg tells us:

“…it’s doubtful that the American public would accept such jarring changes.”

That’s an interesting political assessment. It would be worth knowing the basis for this assertion. We had comparably jarring changes in the form of Social Security tax increases in the decades of 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s. There was no massive tax revolt against any of these tax increases; what has convinced Bloomberg that we can never again have a comparable increase in the payroll tax?

A piece of evidence suggesting that tax increases necessary to support Social Security might be politically viable is the fact that few people even noticed the 2.0 percentage point increase in the payroll tax at the start of 2013 when the payroll tax holiday ended. This was at a time when the labor market was still very weak from the recession and wages had been stagnant for more than a decade. (A survey conducted for the National Academy for Social Insurance also found that people were willing to pay higher taxes to support the scheduled level of Social Security benefits.)

Given this history and evidence, Bloomberg’s claim that the public won’t tolerate the sort of tax increases necessary to fully fund Social Security looks like an unsupported assertion.

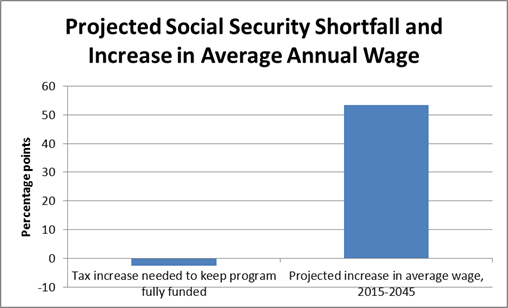

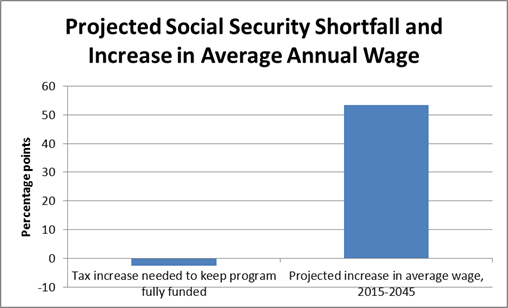

The other point on this topic is that economists usually believe that workers care first and foremost about their after-tax wage, not the tax rate. The Social Security trustees project that real before-tax wages will rise on average by more than 50 percent over the next three decades. By comparison, the tax increase needed to fully fund Social Security seems relatively small, as shown below.

Source: Social Security trustees report, 2015 and author’s calculations.

Most workers have not seen their wages increase as much as the average wage over the last four decades since a disproportionate share went to those at top. These are people like CEOs, Wall Street traders, and doctors and other highly paid professionals. Workers stand to lose much more in terms of after-tax income if this upward redistribution continues over the next three decades than they would from the “jarring” Social Security tax increase that Bloomberg feels the need to warn us about.

So, of course people could get really worried about Social Security, as Bloomberg wants, or they can focus on the upward redistribution which will have far more impact on their well-being and that of their children. (Yes, this is the topic of my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer, which can be downloaded for free.)

The Social Security scare story is a long established Washington ritual. Bloomberg news decided to bring it out again in time for Halloween. The basic story is that the Social Security trust fund is projected to face a shortfall in less than two decades. This means that unless Congress appropriates additional revenue, the program is projected to only be able to pay a bit more than 80 percent of scheduled benefits.

This much is not really in dispute. The question is how much should we be worried about this projected shortfall and what should we do about it. Bloomberg’s answer to the first question is that we should be very worried. It goes through the list of potential fixes and implies that all would be difficult or impossible.

I will just take one potential fix, which is raising the payroll tax by 2.58 percentage points to cover the projected shortfall. Bloomberg tells us:

“…it’s doubtful that the American public would accept such jarring changes.”

That’s an interesting political assessment. It would be worth knowing the basis for this assertion. We had comparably jarring changes in the form of Social Security tax increases in the decades of 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s. There was no massive tax revolt against any of these tax increases; what has convinced Bloomberg that we can never again have a comparable increase in the payroll tax?

A piece of evidence suggesting that tax increases necessary to support Social Security might be politically viable is the fact that few people even noticed the 2.0 percentage point increase in the payroll tax at the start of 2013 when the payroll tax holiday ended. This was at a time when the labor market was still very weak from the recession and wages had been stagnant for more than a decade. (A survey conducted for the National Academy for Social Insurance also found that people were willing to pay higher taxes to support the scheduled level of Social Security benefits.)

Given this history and evidence, Bloomberg’s claim that the public won’t tolerate the sort of tax increases necessary to fully fund Social Security looks like an unsupported assertion.

The other point on this topic is that economists usually believe that workers care first and foremost about their after-tax wage, not the tax rate. The Social Security trustees project that real before-tax wages will rise on average by more than 50 percent over the next three decades. By comparison, the tax increase needed to fully fund Social Security seems relatively small, as shown below.

Source: Social Security trustees report, 2015 and author’s calculations.

Most workers have not seen their wages increase as much as the average wage over the last four decades since a disproportionate share went to those at top. These are people like CEOs, Wall Street traders, and doctors and other highly paid professionals. Workers stand to lose much more in terms of after-tax income if this upward redistribution continues over the next three decades than they would from the “jarring” Social Security tax increase that Bloomberg feels the need to warn us about.

So, of course people could get really worried about Social Security, as Bloomberg wants, or they can focus on the upward redistribution which will have far more impact on their well-being and that of their children. (Yes, this is the topic of my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer, which can be downloaded for free.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Just kidding. Actually, insurance costs have slowed sharply in the years since the Affordable Care Act was passed, but it is unlikely many readers of the NYT would know this. Instead, it has focused on the large increase (not levels) in premium costs for the relatively small segment of the population insured on the exchanges. In keeping with this pattern, it gives us a front page piece telling readers about the 25 percent average increase in premiums facing people on the exchange this year. There are two points to keep in mind on this issue.

First, the focus on premiums is exclusively on the relatively small segment of the population getting insurance through the exchanges and specifically through the exchanges managed through the federal government. According to the latest numbers, 12.7 million people are now getting insurance through the exchanges (roughly 4.0 percent of the total population). This article refers to the premiums being paid by the 9.6 million people insured through the federally managed exchange (3.0 percent of the total population). Many states, such as California, have well run exchanges that have been more successful in keeping cost increases down.

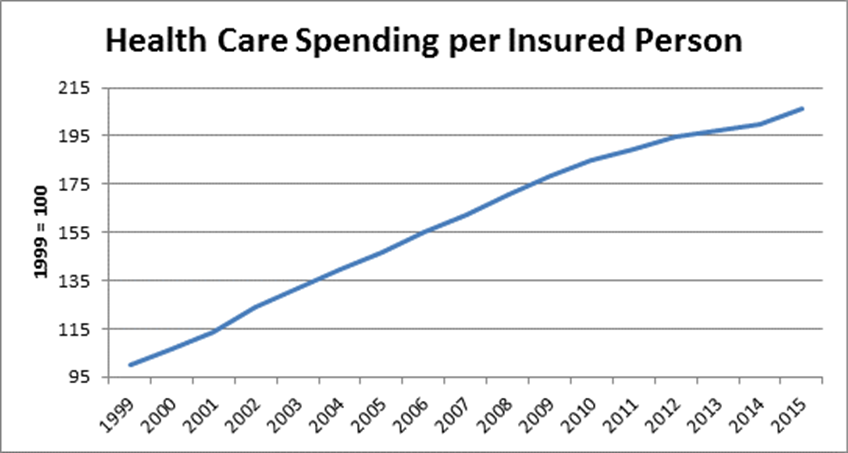

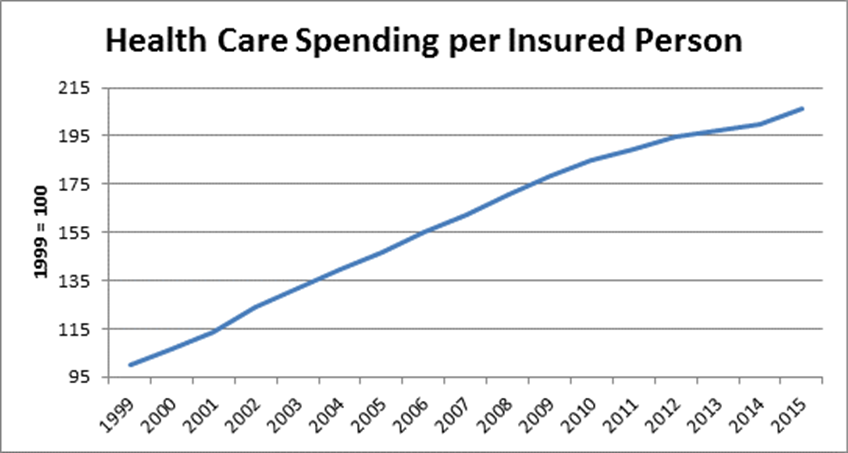

There are two reasons that costs on the exchanges have been rising rapidly. The first is that insurers probably priced their policies too low initially. Even with the increases this year premium prices are still lower than had been expected in 2010 when the law was passed. In fact, there has been a sharp slowing in the pace of health care cost growth in the last six years. While not all of this was due to the ACA, it was undoubtedly a factor in this slowdown. In the years from 1999 to 2010, health care costs per insured person rose at an average annual rate of 5.7 percent. In the years from 2010 to 2015 costs per insured person rose at an average rate of just 2.3 percent.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The other reason that premiums on the exchanges have risen rapidly is that more people are stiill getting insurance through employers than had been expected. The people who get insurance through employers tend to be healthier on average than the population as a whole. The Obama administration expected that more employers would stop providing insurance, sending their workers to get insurance on the exchanges. Since they have continued to provide insurance, the mix of people getting insurance through the exchanges is less healthy than had been expected.

Note that this has nothing to do with the “young invincible” story that had been widely touted in the years leading up to the ACA. The problem is not that healthy young people are not signing up. The problem is simply that healthy people of all ages are getting their insurance elsewhere. The overall percentage of the population getting insured is higher than projected, not lower as the young invincible silliness would imply.

Addendum

Robert Salzberg reminds me that the vast majority of people buying insurance in the exchanges get subsidies. For most people these subsidies will fully cover these cost increases. Even after the increases noted in this NYT article, almost 80 percent of the people buying insurance in the exchanges will be able to get a plan for less than $100 per month.

Just kidding. Actually, insurance costs have slowed sharply in the years since the Affordable Care Act was passed, but it is unlikely many readers of the NYT would know this. Instead, it has focused on the large increase (not levels) in premium costs for the relatively small segment of the population insured on the exchanges. In keeping with this pattern, it gives us a front page piece telling readers about the 25 percent average increase in premiums facing people on the exchange this year. There are two points to keep in mind on this issue.

First, the focus on premiums is exclusively on the relatively small segment of the population getting insurance through the exchanges and specifically through the exchanges managed through the federal government. According to the latest numbers, 12.7 million people are now getting insurance through the exchanges (roughly 4.0 percent of the total population). This article refers to the premiums being paid by the 9.6 million people insured through the federally managed exchange (3.0 percent of the total population). Many states, such as California, have well run exchanges that have been more successful in keeping cost increases down.

There are two reasons that costs on the exchanges have been rising rapidly. The first is that insurers probably priced their policies too low initially. Even with the increases this year premium prices are still lower than had been expected in 2010 when the law was passed. In fact, there has been a sharp slowing in the pace of health care cost growth in the last six years. While not all of this was due to the ACA, it was undoubtedly a factor in this slowdown. In the years from 1999 to 2010, health care costs per insured person rose at an average annual rate of 5.7 percent. In the years from 2010 to 2015 costs per insured person rose at an average rate of just 2.3 percent.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The other reason that premiums on the exchanges have risen rapidly is that more people are stiill getting insurance through employers than had been expected. The people who get insurance through employers tend to be healthier on average than the population as a whole. The Obama administration expected that more employers would stop providing insurance, sending their workers to get insurance on the exchanges. Since they have continued to provide insurance, the mix of people getting insurance through the exchanges is less healthy than had been expected.

Note that this has nothing to do with the “young invincible” story that had been widely touted in the years leading up to the ACA. The problem is not that healthy young people are not signing up. The problem is simply that healthy people of all ages are getting their insurance elsewhere. The overall percentage of the population getting insured is higher than projected, not lower as the young invincible silliness would imply.

Addendum

Robert Salzberg reminds me that the vast majority of people buying insurance in the exchanges get subsidies. For most people these subsidies will fully cover these cost increases. Even after the increases noted in this NYT article, almost 80 percent of the people buying insurance in the exchanges will be able to get a plan for less than $100 per month.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, that is what he advocated in this column calling on people to vote for Hillary Clinton and Republican members of Congress. The Republicans are a party of climate deniers. Perhaps Samuelson doesn’t know this, but who cares. He urged the readers of his column to support a party that denies well-established science on climate change.

Yes, that is what he advocated in this column calling on people to vote for Hillary Clinton and Republican members of Congress. The Republicans are a party of climate deniers. Perhaps Samuelson doesn’t know this, but who cares. He urged the readers of his column to support a party that denies well-established science on climate change.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We continue to see a steady drumbeat of news stories and opinion pieces about the problem of men, and especially less-educated men, in the modern economy. The pieces always start with the fact that large numbers of prime-age men (ages 25–54) have dropped out of the labor force. The latest entry is a NYT column by Susan Chira that highlighted recent research showing that a large percentage of men who are not in the labor force are in poor health and frequent users of pain medication.

While this is interesting and useful research, it is unlikely that it explains the decline in employment among prime-age men. The reason, as I (along with Jared Bernstein) continually point out, is that there has been a similar drop in the employment rates of prime-age women since 2000.

The issue here should be straightforward. If we see drops in employment rates for both prime-age men and women, then it is not likely that they will be explained by problems that are unique to men. More likely, the problems stem from the overall state of the economy. In other words, the problem is with the people who design policy, not with the men who have dropped out of the workforce.

This doesn’t mean that non-employed men are not facing real problems. Undoubtedly many are, although the extent to which these problems are the result of their unemployment or a cause will often not be clear. Nonetheless, steps that can improve public health will be a good thing, but the better place to look to solve the problem of unemployment is Washington.

We continue to see a steady drumbeat of news stories and opinion pieces about the problem of men, and especially less-educated men, in the modern economy. The pieces always start with the fact that large numbers of prime-age men (ages 25–54) have dropped out of the labor force. The latest entry is a NYT column by Susan Chira that highlighted recent research showing that a large percentage of men who are not in the labor force are in poor health and frequent users of pain medication.

While this is interesting and useful research, it is unlikely that it explains the decline in employment among prime-age men. The reason, as I (along with Jared Bernstein) continually point out, is that there has been a similar drop in the employment rates of prime-age women since 2000.

The issue here should be straightforward. If we see drops in employment rates for both prime-age men and women, then it is not likely that they will be explained by problems that are unique to men. More likely, the problems stem from the overall state of the economy. In other words, the problem is with the people who design policy, not with the men who have dropped out of the workforce.

This doesn’t mean that non-employed men are not facing real problems. Undoubtedly many are, although the extent to which these problems are the result of their unemployment or a cause will often not be clear. Nonetheless, steps that can improve public health will be a good thing, but the better place to look to solve the problem of unemployment is Washington.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

By Lara Merling and Dean Baker

The Peter Peterson-Washington Post deficit hawk gang keep trying to scare us in cutting Social Security and Medicare. If we don’t cut these programs now, then at some point in the future we might have to cut these program or RAISE TAXES.

There are many good reasons not to take the advice of the deficit hawks, but the most immediate one is that our economy is suffering from a deficit that is too small, not too large. The point is straight forward, the economy needs more demand, which we could get from larger budget deficits. More demand would lead to more output and employment. It would also cause firms to invest more, which would make us richer in the future.

The flip side in this story is that because we have not been investing as much as we would in a fully employed economy, our potential level of output is lower today than if we had remained near full employment since the downturn in 2008. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that potential GDP in 2016 is down by 10.5 percent (almost $2.0 trillion) from the level it had projected for 2016 back in 2008, before the downturn.

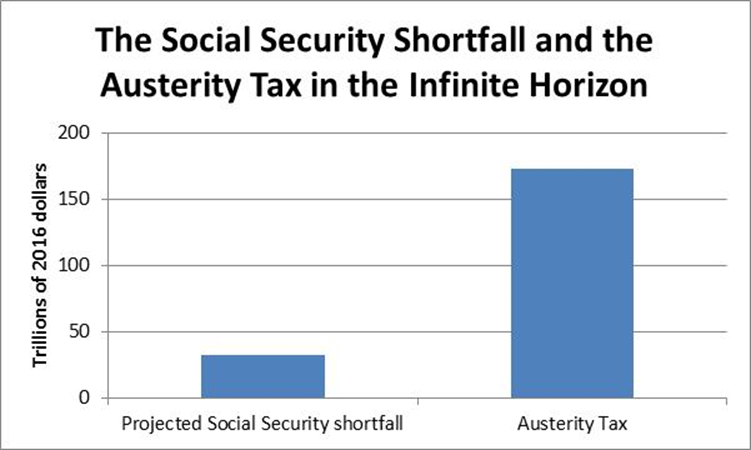

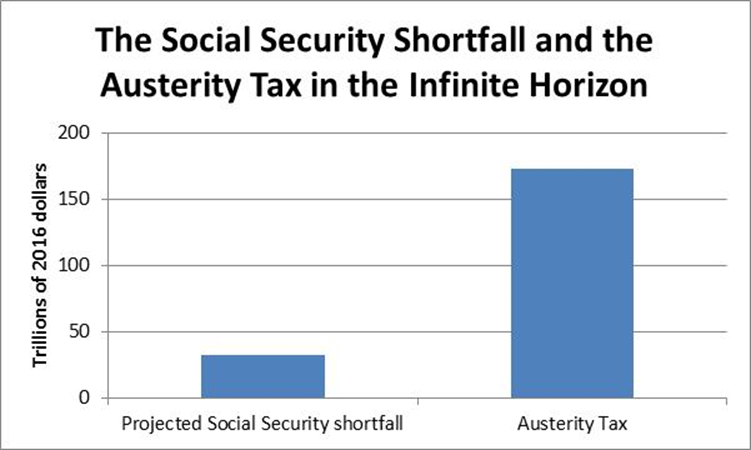

This is real money, over $6,200 per person. But if we want to have a little fun, we can use a tactic developed by the deficit hawks. We can calculate the cost of austerity over the infinite horizon. This is a simple story. We just assume that we will never get back the potential GDP lost as a result of the weak growth of the last eight years. Carrying this the lost 10.5 percent of GDP out to the infinite future and using a 2.9 percent real discount rate gives us $172.94 trillion in lost output. This is the size of the austerity tax for all future time. It comes to more than $500,000 for every person in the country.

By comparison, we can look at the projected Social Security shortfall for the infinite horizon. According to the most recent Social Security Trustees Report, this comes to $32.1 trillion. (Almost two thirds of this occurs after the 75-year projection period.) Undoubtedly, many deficit hawks hope that people would be scared by this number. But compared to the austerity tax imposed by the deficit hawks, it doesn’t look like a big deal.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report and Author’s Calculations.

By Lara Merling and Dean Baker

The Peter Peterson-Washington Post deficit hawk gang keep trying to scare us in cutting Social Security and Medicare. If we don’t cut these programs now, then at some point in the future we might have to cut these program or RAISE TAXES.

There are many good reasons not to take the advice of the deficit hawks, but the most immediate one is that our economy is suffering from a deficit that is too small, not too large. The point is straight forward, the economy needs more demand, which we could get from larger budget deficits. More demand would lead to more output and employment. It would also cause firms to invest more, which would make us richer in the future.

The flip side in this story is that because we have not been investing as much as we would in a fully employed economy, our potential level of output is lower today than if we had remained near full employment since the downturn in 2008. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that potential GDP in 2016 is down by 10.5 percent (almost $2.0 trillion) from the level it had projected for 2016 back in 2008, before the downturn.

This is real money, over $6,200 per person. But if we want to have a little fun, we can use a tactic developed by the deficit hawks. We can calculate the cost of austerity over the infinite horizon. This is a simple story. We just assume that we will never get back the potential GDP lost as a result of the weak growth of the last eight years. Carrying this the lost 10.5 percent of GDP out to the infinite future and using a 2.9 percent real discount rate gives us $172.94 trillion in lost output. This is the size of the austerity tax for all future time. It comes to more than $500,000 for every person in the country.

By comparison, we can look at the projected Social Security shortfall for the infinite horizon. According to the most recent Social Security Trustees Report, this comes to $32.1 trillion. (Almost two thirds of this occurs after the 75-year projection period.) Undoubtedly, many deficit hawks hope that people would be scared by this number. But compared to the austerity tax imposed by the deficit hawks, it doesn’t look like a big deal.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report and Author’s Calculations.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had an interesting piece about Iclusig, a cancer drug that now sells for almost $200,000 a year. The piece discussed the pricing pattern for cancer drugs. It noted that the pricing of Iclusig did not follow the normal pattern, with the price soaring as its range of approved uses was limited by the Food and Drug Administration.

While it presented this as evidence of this not being a normal market, the piece never made the obvious point: the drug market is certainly not normal because the government grants patent monopolies and other forms of protection. Without these government granted monopolies almost all drugs would be cheap. Certainly none would sell for anything close to $200,000. While it is necessary to pay for research, they are other mechanisms that would almost certainly be more efficient and less prone to corruption than patent monopolies.

The Washington Post had an interesting piece about Iclusig, a cancer drug that now sells for almost $200,000 a year. The piece discussed the pricing pattern for cancer drugs. It noted that the pricing of Iclusig did not follow the normal pattern, with the price soaring as its range of approved uses was limited by the Food and Drug Administration.

While it presented this as evidence of this not being a normal market, the piece never made the obvious point: the drug market is certainly not normal because the government grants patent monopolies and other forms of protection. Without these government granted monopolies almost all drugs would be cheap. Certainly none would sell for anything close to $200,000. While it is necessary to pay for research, they are other mechanisms that would almost certainly be more efficient and less prone to corruption than patent monopolies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

At the debate last night, moderator Chris Wallace challenged both candidates on the question of cutting Social Security and Medicare. The implication is that the country is threatened by the prospect of out of control government deficits. The question was misguided on several grounds.

First, as a matter of law the Social Security program can only spend money that is in the trust fund. This means that, unless Congress changes the law, the program can never be a cause of runaway deficits.

Second, it is important to note that the size of the projected shortfall in the Medicare Part A program (the portion funded by its own tax) has fallen sharply in the Obama years. The shortfall for the 75-year planning horizon was projected at 3.53 percentage points of payroll in 2009, the first year of the Obama presidency. It has now fallen by 80 percent to just 0.73 percent of payroll. This reduction is due to a sharp slowdown in the projected growth of health care costs. Some of this predates the Affordable Care Act (ACA), but some of the slowdown is undoubtedly attributable to the impact of the ACA.

Anyhow, the implication of Wallace’s question, that these programs are somehow out of control and require some near term fix, is not supported by the data. We will have to make changes to maintain full funding for Social Security, but there is no urgency to this issue.

On the more general point of deficits, the country’s problem since the crash in 2008 has been deficits that are too small, not too large. The main factor holding back the economy has been a lack of demand, not a lack of supply. Deficits create more demand, either directly through government spending or indirectly through increased consumption. If we had larger deficits in recent years we would have seen more GDP, more jobs, and, due to a tighter labor market, higher wages.

The problem of too small deficits is not just a short-term issue. A smaller economy means less investment in new plant and equipment and research. This reduces the economy’s capacity in the future. In the same vein, high rates of unemployment cause people to permanently drop out of the labor force, reducing our future labor supply if these people become unemployable. (Having unemployed parents is also very bad news for the kids who will have worse life prospects.)

The Congressional Budget Office now puts potential GDP at about 10 percent lower for 2016 than its projection from 2008, before the recession. Much of this drop is due the decision to run smaller deficits and prevent the economy from reaching its potential level of output. We can think of this loss of potential output as a “austerity tax.” It currently is at close to $2 trillion a year or more than $6,000 for every person in the country.

It is unfortunate that Wallace chose to devote valuable debate time to a non-problem while ignoring the huge problem of needless unemployment and lost output due to government deficits that are too small.

At the debate last night, moderator Chris Wallace challenged both candidates on the question of cutting Social Security and Medicare. The implication is that the country is threatened by the prospect of out of control government deficits. The question was misguided on several grounds.

First, as a matter of law the Social Security program can only spend money that is in the trust fund. This means that, unless Congress changes the law, the program can never be a cause of runaway deficits.

Second, it is important to note that the size of the projected shortfall in the Medicare Part A program (the portion funded by its own tax) has fallen sharply in the Obama years. The shortfall for the 75-year planning horizon was projected at 3.53 percentage points of payroll in 2009, the first year of the Obama presidency. It has now fallen by 80 percent to just 0.73 percent of payroll. This reduction is due to a sharp slowdown in the projected growth of health care costs. Some of this predates the Affordable Care Act (ACA), but some of the slowdown is undoubtedly attributable to the impact of the ACA.

Anyhow, the implication of Wallace’s question, that these programs are somehow out of control and require some near term fix, is not supported by the data. We will have to make changes to maintain full funding for Social Security, but there is no urgency to this issue.

On the more general point of deficits, the country’s problem since the crash in 2008 has been deficits that are too small, not too large. The main factor holding back the economy has been a lack of demand, not a lack of supply. Deficits create more demand, either directly through government spending or indirectly through increased consumption. If we had larger deficits in recent years we would have seen more GDP, more jobs, and, due to a tighter labor market, higher wages.

The problem of too small deficits is not just a short-term issue. A smaller economy means less investment in new plant and equipment and research. This reduces the economy’s capacity in the future. In the same vein, high rates of unemployment cause people to permanently drop out of the labor force, reducing our future labor supply if these people become unemployable. (Having unemployed parents is also very bad news for the kids who will have worse life prospects.)

The Congressional Budget Office now puts potential GDP at about 10 percent lower for 2016 than its projection from 2008, before the recession. Much of this drop is due the decision to run smaller deficits and prevent the economy from reaching its potential level of output. We can think of this loss of potential output as a “austerity tax.” It currently is at close to $2 trillion a year or more than $6,000 for every person in the country.

It is unfortunate that Wallace chose to devote valuable debate time to a non-problem while ignoring the huge problem of needless unemployment and lost output due to government deficits that are too small.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post keeps pushing the “hard to get good help” line, this time in reference to China. It told readers how the country is ending its one-child policy, but that many families are likely to still decide not to have more than one kid. The piece then told readers:

“That’s a problem for China. The people born in Mao’s era are growing old, and there will be far fewer people of working age to bear the economic burden.”

Actually, the declining ratio of workers to retirees is likely to have relatively little impact on China’s economy since the impact of even modest rates of productivity growth swamps the impact of demographics as third grade arithmetic students everywhere know.

It is striking to see the fears of running out of workers co-exist with the regular stories in the media about robots taking all the jobs. This shows the unbelievable bankruptcy of economic debate in the United States that these two directly opposing concerns exist side by side among people who consider themselves knowledgeable about economic policy.

Note: correction made, thanks heropass.

The Washington Post keeps pushing the “hard to get good help” line, this time in reference to China. It told readers how the country is ending its one-child policy, but that many families are likely to still decide not to have more than one kid. The piece then told readers:

“That’s a problem for China. The people born in Mao’s era are growing old, and there will be far fewer people of working age to bear the economic burden.”

Actually, the declining ratio of workers to retirees is likely to have relatively little impact on China’s economy since the impact of even modest rates of productivity growth swamps the impact of demographics as third grade arithmetic students everywhere know.

It is striking to see the fears of running out of workers co-exist with the regular stories in the media about robots taking all the jobs. This shows the unbelievable bankruptcy of economic debate in the United States that these two directly opposing concerns exist side by side among people who consider themselves knowledgeable about economic policy.

Note: correction made, thanks heropass.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión