Steve Mufson picked up the Washington elite’s quest to get more money for some of the country’s biggest corporations by telling readers that the Export-Import Bank is not really corporate welfare because it makes a profit.

“It isn’t much welfare; the bank has an excellent lending record — a default rate of 0.175 percent as of September 2014 and a 50 percent recovery rate on defaulted loans — and the appropriation for about $110 million covers administrative expenses.”

This displays the sort of basic confusion on economics that readers have come to expect from the Washington Post. The point is that the government is subsidizing loans to some of the largest companies in the country. By relying on the creditworthiness of the U.S. government, the Ex-Im Bank is allowing a small number of huge companies, who always account for the overwhelming majority of Ex-Im bank lending, to get loans at below the market rate. This is similar to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac which allow mortgage holders to get mortgages at a below market rate by providing a government guarantee.

This is a clear subsidy outside of Washington Post land. If it serves a public purpose, for example promoting homeownership, then it is arguably a good policy. But the nonsense and name-calling being put forth to justify the Ex-Im bank hardly make the case.

Anyhow, since the honchos will undoubtedly keep pushing the Ex-Im Bank until Boeing gets its money, how about a compromise? Any company that gets below market interest loans as a result of Ex-Im bank subsidies has to agree not to pay its top executives more than 10 times the president’s salary ($400k) for a five year period. That’s a $4 million hard cap on all compensation. The company’s top execs and all board members sign a certification to this effect promising them 10 years hard time if they lie.

What do you say folks? Can the CEO of Boeing and GE get by on $4 million a year? There are jobs at stake, right?

Steve Mufson picked up the Washington elite’s quest to get more money for some of the country’s biggest corporations by telling readers that the Export-Import Bank is not really corporate welfare because it makes a profit.

“It isn’t much welfare; the bank has an excellent lending record — a default rate of 0.175 percent as of September 2014 and a 50 percent recovery rate on defaulted loans — and the appropriation for about $110 million covers administrative expenses.”

This displays the sort of basic confusion on economics that readers have come to expect from the Washington Post. The point is that the government is subsidizing loans to some of the largest companies in the country. By relying on the creditworthiness of the U.S. government, the Ex-Im Bank is allowing a small number of huge companies, who always account for the overwhelming majority of Ex-Im bank lending, to get loans at below the market rate. This is similar to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac which allow mortgage holders to get mortgages at a below market rate by providing a government guarantee.

This is a clear subsidy outside of Washington Post land. If it serves a public purpose, for example promoting homeownership, then it is arguably a good policy. But the nonsense and name-calling being put forth to justify the Ex-Im bank hardly make the case.

Anyhow, since the honchos will undoubtedly keep pushing the Ex-Im Bank until Boeing gets its money, how about a compromise? Any company that gets below market interest loans as a result of Ex-Im bank subsidies has to agree not to pay its top executives more than 10 times the president’s salary ($400k) for a five year period. That’s a $4 million hard cap on all compensation. The company’s top execs and all board members sign a certification to this effect promising them 10 years hard time if they lie.

What do you say folks? Can the CEO of Boeing and GE get by on $4 million a year? There are jobs at stake, right?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yesterday, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump released his plan for changing the tax code. The basic story is that he would give big tax cuts across the board, with the largest tax cuts going to the wealthy. He assured everyone that it will be revenue neutral since it would lead to a huge spurt of economic growth. (His number was 6.0 percent, topping Jeb Bush’s 4.0 percent by two full percentage points.)

Many of the reports on the plan did note the growth assumption and pointed out that few, if any, economists took it seriously. As a practical matter, we have seen this one before. Ronald Reagan put in place a large tax cut in the 1980s and George W. Bush did the same in the last decade. You have to try very hard to find a positive growth effect from either. Certainly no one could make the case with a straight face that these sorts of proposals could even get us to Bush’s 4.0 percent number, much less Trump’s 6.0 percent.

But apart from what the tax cuts may or may not be able to do in terms of growth, there is also the matter of how the Federal Reserve Board would react. If that sounds strange to you then you should be very angry at the reporters at your favorite news outlet, because they should have been talking about this.

Suppose that Donald Trump’s tax cut really is the magic elixir that would get the economy to 6.0 percent annual growth. But what if the people at the Fed’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) don’t recognize this fact? Suppose the FOMC thinks the economy is still bound by the pre-Trump tax cut rules and believes that inflation will start to accelerate out of control if the unemployment rate falls much below its current 5.1 percent level.

In this case, we would expect to see the Fed raise interest rates sharply as they saw the Trump tax cuts boosting growth. Higher interest rates would slow house buying and new construction, discourage car sales, and put a crimp in both public and private investment. If the Fed raises interest rates high enough, it could fully offset the boost that Trump’s tax cut is giving to the economy. In this case, even though the Trump tax cuts might have been the best thing for the economy since the Internet (okay, better than the Internet), we wouldn’t see any dividend because the Fed would not allow it.

For this reason, the Fed’s likely response to a tax cut is a fundamental question that reporters should be asking. If the Fed is likely to simply slam on the brakes to offset any possible stimulus, then a tax plan will have little prospect of providing a growth dividend.

Since the press have been obsessing (rightly) over the possibility that the Fed is about to embark on a series of rate hikes, it would be reasonable to believe that someone would think to bring together the Fed’s interest rate policy and the candidate’s economic plans. Thus far it seems no reporters have discovered the connection.

Note: Typo corrected.

Yesterday, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump released his plan for changing the tax code. The basic story is that he would give big tax cuts across the board, with the largest tax cuts going to the wealthy. He assured everyone that it will be revenue neutral since it would lead to a huge spurt of economic growth. (His number was 6.0 percent, topping Jeb Bush’s 4.0 percent by two full percentage points.)

Many of the reports on the plan did note the growth assumption and pointed out that few, if any, economists took it seriously. As a practical matter, we have seen this one before. Ronald Reagan put in place a large tax cut in the 1980s and George W. Bush did the same in the last decade. You have to try very hard to find a positive growth effect from either. Certainly no one could make the case with a straight face that these sorts of proposals could even get us to Bush’s 4.0 percent number, much less Trump’s 6.0 percent.

But apart from what the tax cuts may or may not be able to do in terms of growth, there is also the matter of how the Federal Reserve Board would react. If that sounds strange to you then you should be very angry at the reporters at your favorite news outlet, because they should have been talking about this.

Suppose that Donald Trump’s tax cut really is the magic elixir that would get the economy to 6.0 percent annual growth. But what if the people at the Fed’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) don’t recognize this fact? Suppose the FOMC thinks the economy is still bound by the pre-Trump tax cut rules and believes that inflation will start to accelerate out of control if the unemployment rate falls much below its current 5.1 percent level.

In this case, we would expect to see the Fed raise interest rates sharply as they saw the Trump tax cuts boosting growth. Higher interest rates would slow house buying and new construction, discourage car sales, and put a crimp in both public and private investment. If the Fed raises interest rates high enough, it could fully offset the boost that Trump’s tax cut is giving to the economy. In this case, even though the Trump tax cuts might have been the best thing for the economy since the Internet (okay, better than the Internet), we wouldn’t see any dividend because the Fed would not allow it.

For this reason, the Fed’s likely response to a tax cut is a fundamental question that reporters should be asking. If the Fed is likely to simply slam on the brakes to offset any possible stimulus, then a tax plan will have little prospect of providing a growth dividend.

Since the press have been obsessing (rightly) over the possibility that the Fed is about to embark on a series of rate hikes, it would be reasonable to believe that someone would think to bring together the Fed’s interest rate policy and the candidate’s economic plans. Thus far it seems no reporters have discovered the connection.

Note: Typo corrected.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In his interview with Donald Trump on 60 Minutes, CBS reporter Scott Pelley felt the need to assert that Social Security is “a basket case.” Actually, according to the latest Social Security trustees report it can pay all scheduled benefits through 2033 with no changes whatsoever. If nothing is ever done to the program it is always projected to be able to pay retirees a larger real benefit than what they get today, or more than 75 percent of scheduled benefits. If we put in place tax increases comparable to those in the 1980s (equal to less than 10 percent of projected wage growth over the next three decades), the program would be fully funded indefinitely.

Given these facts, it would be interesting to know the basis for Pelley’s decision to call the program a basket case. Its prospects over the next two decades are almost certainly better than those of his network.

In his interview with Donald Trump on 60 Minutes, CBS reporter Scott Pelley felt the need to assert that Social Security is “a basket case.” Actually, according to the latest Social Security trustees report it can pay all scheduled benefits through 2033 with no changes whatsoever. If nothing is ever done to the program it is always projected to be able to pay retirees a larger real benefit than what they get today, or more than 75 percent of scheduled benefits. If we put in place tax increases comparable to those in the 1980s (equal to less than 10 percent of projected wage growth over the next three decades), the program would be fully funded indefinitely.

Given these facts, it would be interesting to know the basis for Pelley’s decision to call the program a basket case. Its prospects over the next two decades are almost certainly better than those of his network.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yeah, we all want our children to enjoy a more comfortable life than we do, but how much more comfortable does it have to be before we feel we have failed them? The Social Security Trustees project that before tax wages will be on average 55 percent higher in real terms than they are today. Suppose that we have a huge 5 percentage point increase in taxes to pay for Social Security and Medicare? That still leaves wages in thirty years more than 45 percent higher than they are today. Would that be unfair to our kids?

Robert Samuelson says it is. He wants us to raise the age at which we would qualify for Social Security to further tilt the income equation in favor of our kids. He says the problem is that middle-income people are living longer than low-income people. While raising the age of eligibility might seem to hurt lower-income people who don’t live as long, he says we can make benefits for the low-income elderly more generous, just as we have done with TANF. (Okay, Samuelson didn’t include the last part about TANF.)

Anyhow, the story of a growing gap in life expectancies is a problem of inequality. Similarly, the reason that many of us would not take for granted that our children will have before-tax wages that are 55 percent higher than today is due to inequality (as in the one percent). The rich got most of the benefits of growth over the last 35 years and it is very possible that they will get most of the benefits over the next 35 years.

And to address this problem, Robert Samuelson wants us to take away Social Security benefits from the middle class and make them work longer. Yes, that make sense. As the ad says, “only in the Washington Post.”

Yeah, we all want our children to enjoy a more comfortable life than we do, but how much more comfortable does it have to be before we feel we have failed them? The Social Security Trustees project that before tax wages will be on average 55 percent higher in real terms than they are today. Suppose that we have a huge 5 percentage point increase in taxes to pay for Social Security and Medicare? That still leaves wages in thirty years more than 45 percent higher than they are today. Would that be unfair to our kids?

Robert Samuelson says it is. He wants us to raise the age at which we would qualify for Social Security to further tilt the income equation in favor of our kids. He says the problem is that middle-income people are living longer than low-income people. While raising the age of eligibility might seem to hurt lower-income people who don’t live as long, he says we can make benefits for the low-income elderly more generous, just as we have done with TANF. (Okay, Samuelson didn’t include the last part about TANF.)

Anyhow, the story of a growing gap in life expectancies is a problem of inequality. Similarly, the reason that many of us would not take for granted that our children will have before-tax wages that are 55 percent higher than today is due to inequality (as in the one percent). The rich got most of the benefits of growth over the last 35 years and it is very possible that they will get most of the benefits over the next 35 years.

And to address this problem, Robert Samuelson wants us to take away Social Security benefits from the middle class and make them work longer. Yes, that make sense. As the ad says, “only in the Washington Post.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Everyone knows that the Washington Post wants to see Social Security and Medicare cut. The paper is constantly pushing this agenda in both its news and opinion pages. But how did the Post decide that President Obama shares this agenda?

It made this assertion in an article headlined, “Obama and Boehner both craved compromise — but could never reach it.” The piece tells readers:

“Those virtues [a desire to compromise for the national good] never resulted in progress, though, even on some of the political goals the men shared: lasting fiscal reforms, a meaningful immigration bill, keeping the government open at times of fiscal disagreement.”

The “lasting fiscal reforms” the Post is referring to here include its desired cuts in Social Security and Medicare. It is not clear why the Post would claim these cuts as a political goal of President Obama. He never claimed cuts to these programs as goals in his two presidential campaigns, nor did he ever try to promote cuts during his years in the Senate.

It is true that he was prepared to agree to cuts as part of a compromise with the Republicans in Congress, but that is hardly evidence that he saw such cuts as an end in itself. It is also worth noting in this respect (since the Post apparently doesn’t have access to such information) that the reductions in projected Medicare spending from lower cost growth vastly exceed the savings from the cuts that were proposed in the 2011 standoff between President Obama and the Republicans in Congress.

This means that if the point was to save the government money, we have already achieved more than the savings that would have come from the cuts being proposed. Of course if the point is to cut benefits to make life harder for seniors receiving Medicare, then further cuts would still be appropriate.

Note:

I see many people disagree with this one. Let me clarify my point. I am fully aware that Obama was prepared to go along with cuts to Social Security and Medicare. I spent a lot of time writing and arguing that this was a bad idea. The question is whether this was a priority that he set for himself.

He certainly never put it forward as a reason to put him in the White House, as in saying “if you elect me, I will cut SS and Medicare,” or a more politic “I will reform entitlements.” In terms of his aides statements on the issue, they always said that the cuts Obama was willing to agree to were compromises in order to preserve funding in other areas and to end the Bush tax cuts for the wealthy.

I really have no clue what is in Obama’s heart of hearts and I suspect the Washington Post does not either. For this reason, it should not asserting that he “craved” cutting benefits.

Everyone knows that the Washington Post wants to see Social Security and Medicare cut. The paper is constantly pushing this agenda in both its news and opinion pages. But how did the Post decide that President Obama shares this agenda?

It made this assertion in an article headlined, “Obama and Boehner both craved compromise — but could never reach it.” The piece tells readers:

“Those virtues [a desire to compromise for the national good] never resulted in progress, though, even on some of the political goals the men shared: lasting fiscal reforms, a meaningful immigration bill, keeping the government open at times of fiscal disagreement.”

The “lasting fiscal reforms” the Post is referring to here include its desired cuts in Social Security and Medicare. It is not clear why the Post would claim these cuts as a political goal of President Obama. He never claimed cuts to these programs as goals in his two presidential campaigns, nor did he ever try to promote cuts during his years in the Senate.

It is true that he was prepared to agree to cuts as part of a compromise with the Republicans in Congress, but that is hardly evidence that he saw such cuts as an end in itself. It is also worth noting in this respect (since the Post apparently doesn’t have access to such information) that the reductions in projected Medicare spending from lower cost growth vastly exceed the savings from the cuts that were proposed in the 2011 standoff between President Obama and the Republicans in Congress.

This means that if the point was to save the government money, we have already achieved more than the savings that would have come from the cuts being proposed. Of course if the point is to cut benefits to make life harder for seniors receiving Medicare, then further cuts would still be appropriate.

Note:

I see many people disagree with this one. Let me clarify my point. I am fully aware that Obama was prepared to go along with cuts to Social Security and Medicare. I spent a lot of time writing and arguing that this was a bad idea. The question is whether this was a priority that he set for himself.

He certainly never put it forward as a reason to put him in the White House, as in saying “if you elect me, I will cut SS and Medicare,” or a more politic “I will reform entitlements.” In terms of his aides statements on the issue, they always said that the cuts Obama was willing to agree to were compromises in order to preserve funding in other areas and to end the Bush tax cuts for the wealthy.

I really have no clue what is in Obama’s heart of hearts and I suspect the Washington Post does not either. For this reason, it should not asserting that he “craved” cutting benefits.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen gave a speech yesterday in which she referred to the value of the Fed’s 2.0 percent inflation target and warned of the uncertainty caused by any effort to raise the target to a higher rate. While having more stable prices is undoubtedly better than having less stable prices, it is a bit bizarre how this 2.0 percent has become the object of worship.

First, to those who care about such things it should be disconcerting that the inflation rate has been consistently below 2.0 percent for the last six years. That might suggest the 2.0 percent target is not all that meaningful. People who expected 2.0 percent inflation would have been shown wrong.

But what seems more striking is that while domestic inflation might be relatively stable, the rate of change of import prices is far from stable. The chart below shows the rate of change of non-oil import prices over the last three decades.

Change in Non-Oil Import Prices (prior 12 months)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen the inflation rate for non-oil import prices fluctuate widely, for example going from -4.2 percent in the period from March 2001 to March 2002 to positive 2.4 percent in the following twelve months. (The fluctations would be larger if we included oil.) Since imports are more than 15 percent of the economy, how can these sorts of fluctuations not pose a problem, but a gradual increase from 2.0 percent to 4.0 percent inflation be a big deal? If there is some logic to the commonly held view that Yellen is espousing, it is hard to see.

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen gave a speech yesterday in which she referred to the value of the Fed’s 2.0 percent inflation target and warned of the uncertainty caused by any effort to raise the target to a higher rate. While having more stable prices is undoubtedly better than having less stable prices, it is a bit bizarre how this 2.0 percent has become the object of worship.

First, to those who care about such things it should be disconcerting that the inflation rate has been consistently below 2.0 percent for the last six years. That might suggest the 2.0 percent target is not all that meaningful. People who expected 2.0 percent inflation would have been shown wrong.

But what seems more striking is that while domestic inflation might be relatively stable, the rate of change of import prices is far from stable. The chart below shows the rate of change of non-oil import prices over the last three decades.

Change in Non-Oil Import Prices (prior 12 months)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen the inflation rate for non-oil import prices fluctuate widely, for example going from -4.2 percent in the period from March 2001 to March 2002 to positive 2.4 percent in the following twelve months. (The fluctations would be larger if we included oil.) Since imports are more than 15 percent of the economy, how can these sorts of fluctuations not pose a problem, but a gradual increase from 2.0 percent to 4.0 percent inflation be a big deal? If there is some logic to the commonly held view that Yellen is espousing, it is hard to see.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Your choices are a professor holding a chair endowed by a pharmaceutical testing company and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). The professor, Darius Lakdawalla, holds the Quintiles chair at the School of Pharmacy at the University of Southern California. In an NYT “Room for Debate” piece on pharmaceutical prices (I was also a contributor), Lakdawalla told readers:

“[D]rug spending has been growing no faster than overall health care spending over the past 10 years.”

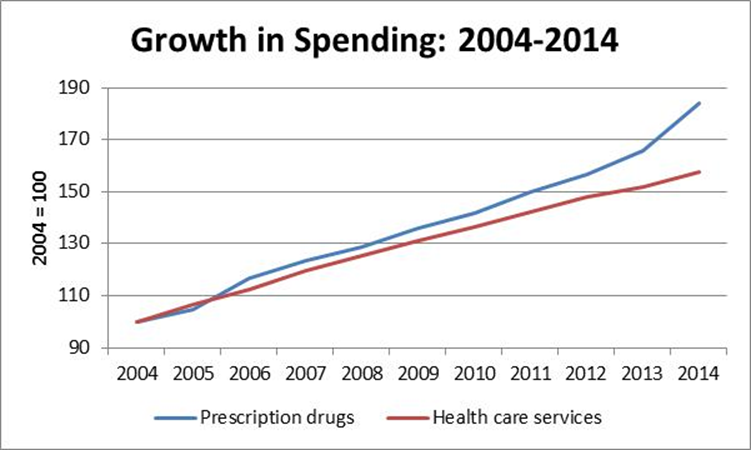

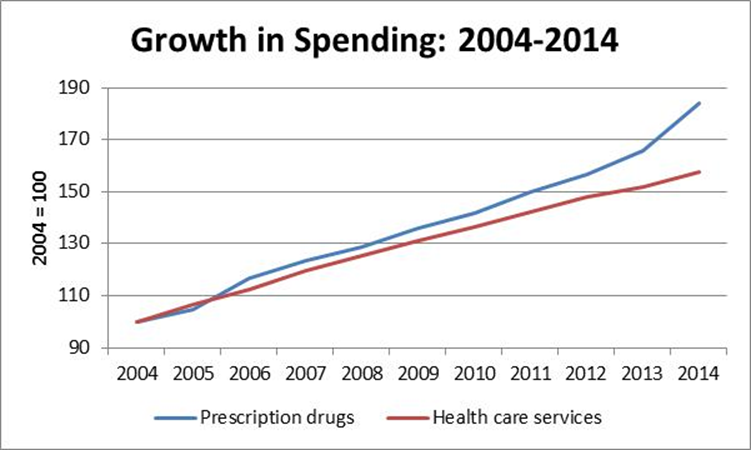

That is not what the good people at BEA say. According to the National Income and Product Accounts (Table 2.4.5U) prescription drug spending increased at average annual rate of 6.3 percent over the years from 2004 to 2014, rising from $203.6 billion in 2004 to $374.7 billion in 2014 (Line 122). By contrast, spending on health care services rose at annual rate of 4.7 percent over this period, going from $1240.1 billion in 2004 to $1954.0 billion in 2014 (Line 168). This is shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The BEA data seem to be showing a very different story that what Professor Lakdawalla is telling us. In fact, over the last five years the gap in growth rates is even larger, with prescription drug spending rising at a 6.2 percent annual rate and spending on health care services rising at just a 3.7 percent annual rate. That difference could explain why presidential candidates apparently feel the need to talk about the cost of prescription drugs.

Your choices are a professor holding a chair endowed by a pharmaceutical testing company and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). The professor, Darius Lakdawalla, holds the Quintiles chair at the School of Pharmacy at the University of Southern California. In an NYT “Room for Debate” piece on pharmaceutical prices (I was also a contributor), Lakdawalla told readers:

“[D]rug spending has been growing no faster than overall health care spending over the past 10 years.”

That is not what the good people at BEA say. According to the National Income and Product Accounts (Table 2.4.5U) prescription drug spending increased at average annual rate of 6.3 percent over the years from 2004 to 2014, rising from $203.6 billion in 2004 to $374.7 billion in 2014 (Line 122). By contrast, spending on health care services rose at annual rate of 4.7 percent over this period, going from $1240.1 billion in 2004 to $1954.0 billion in 2014 (Line 168). This is shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The BEA data seem to be showing a very different story that what Professor Lakdawalla is telling us. In fact, over the last five years the gap in growth rates is even larger, with prescription drug spending rising at a 6.2 percent annual rate and spending on health care services rising at just a 3.7 percent annual rate. That difference could explain why presidential candidates apparently feel the need to talk about the cost of prescription drugs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There is an annoying tendency among elite types to assume that their ignorance on important issues is shared by others. Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson gave us a great example of the effort to project his misunderstanding of the economy when he told readers:

“Over the past decade, there has been a profound shift in its public standing. Before the 2008–09 financial crisis, the Fed enjoyed enormous prestige and freedom of action. All the Fed had to do, it seemed, was tweak short-term interest rates to keep expansions long and recessions short. What’s clear now is that we vastly exaggerated the Fed’s powers of economic management.”

Sorry folks, but Samuelson is describing his own need for rethinking, not the need for those with a better understanding of the economy. We had recalled the weak recovery from the 2001 recession. While the GDP recovery was impressive, the labor market recovery was not. While the recession officially ended in December of 2001, we continued to lose jobs all through 2002 and until September of 2003. We didn’t get back the jobs lost in the downturn until January of 2005. At the time this was the longest period without job growth since the Great Depression. The Fed’s pushing its short-term interest rate down to just 1.0 percent did not seem to help much.

This led us to be very concerned about the difficulty in recovering from the recession that would inevitably follow the collapse of the housing bubble, which was visible to those with clear eyes long before it burst. So the confusion on these issues belongs to Samuelson, not to “we.”

Unfortunately his confusion continues. He tells readers that the economy is near full employment. This is only true if we think that millions of people in their thirties and forties have opted for early retirement since the beginning of the recession. These people have dropped out of the labor force and are therefore not counted as unemployed. The amount of involuntary part-time and quit rates are still both at recession levels.

He then says:

“the financial crisis and Great Recession so traumatized consumers and businesses that they reined in their spending and risk-taking.”

Nope, consumption is actually very high relative to disposable income or GDP. This is a fact that is well know to those with access to government GDP data (i.e. everyone). Similarly, the investment share of GDP is pretty much back to its pre-recession level.

The explanation for the continued doldrums is actually very simple. We have nothing to fill the demand gap created by a trade deficit of 3 percent of GDP (@ $500 billion a year). In the last decade we had the housing bubble, but in the absence of the bubble, there is no easy way to fill that gap. We could do it with budget deficits, but that gets our friends at the Post really upset. Instead, we get high unemployment and weak wage growth, and people are unhappy. It’s all so complicated.

There is an annoying tendency among elite types to assume that their ignorance on important issues is shared by others. Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson gave us a great example of the effort to project his misunderstanding of the economy when he told readers:

“Over the past decade, there has been a profound shift in its public standing. Before the 2008–09 financial crisis, the Fed enjoyed enormous prestige and freedom of action. All the Fed had to do, it seemed, was tweak short-term interest rates to keep expansions long and recessions short. What’s clear now is that we vastly exaggerated the Fed’s powers of economic management.”

Sorry folks, but Samuelson is describing his own need for rethinking, not the need for those with a better understanding of the economy. We had recalled the weak recovery from the 2001 recession. While the GDP recovery was impressive, the labor market recovery was not. While the recession officially ended in December of 2001, we continued to lose jobs all through 2002 and until September of 2003. We didn’t get back the jobs lost in the downturn until January of 2005. At the time this was the longest period without job growth since the Great Depression. The Fed’s pushing its short-term interest rate down to just 1.0 percent did not seem to help much.

This led us to be very concerned about the difficulty in recovering from the recession that would inevitably follow the collapse of the housing bubble, which was visible to those with clear eyes long before it burst. So the confusion on these issues belongs to Samuelson, not to “we.”

Unfortunately his confusion continues. He tells readers that the economy is near full employment. This is only true if we think that millions of people in their thirties and forties have opted for early retirement since the beginning of the recession. These people have dropped out of the labor force and are therefore not counted as unemployed. The amount of involuntary part-time and quit rates are still both at recession levels.

He then says:

“the financial crisis and Great Recession so traumatized consumers and businesses that they reined in their spending and risk-taking.”

Nope, consumption is actually very high relative to disposable income or GDP. This is a fact that is well know to those with access to government GDP data (i.e. everyone). Similarly, the investment share of GDP is pretty much back to its pre-recession level.

The explanation for the continued doldrums is actually very simple. We have nothing to fill the demand gap created by a trade deficit of 3 percent of GDP (@ $500 billion a year). In the last decade we had the housing bubble, but in the absence of the bubble, there is no easy way to fill that gap. We could do it with budget deficits, but that gets our friends at the Post really upset. Instead, we get high unemployment and weak wage growth, and people are unhappy. It’s all so complicated.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión