James Stewart has a piece in the NYT telling readers that if Greece were to leave the euro it would face a disaster. The headline warns readers, “imagine Argentina, but much worse.” The article includes several assertions that are misleading or false.

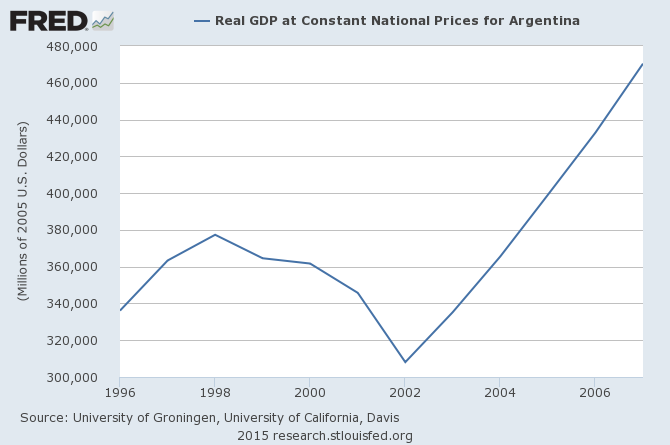

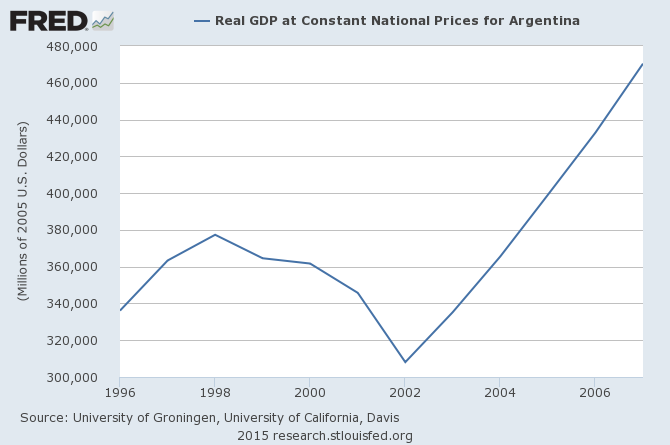

First, it is difficult to describe the default in Argentina as a disaster. The economy had been plummeting prior to the default, which occurred at the end of the year in 2001. The country’s GDP had actually fallen more before the default than it did after the default. (This is not entirely clear on the graph, since the data is annual. At the point where the default took place in December of 2001, Argentina’s GDP was already well below the year-round average.) While the economy did fall more sharply after the default, it soon rebounded and by the end of 2003 it had regained all the ground lost following the default.

Argentina’s economy continued to grow rapidly for several more years, rising above pre-recession levels in 2004. Given the fuller picture, it is difficult to see the default as an especially disastrous event even if it did lead to several months of uncertainty for the people of Argentina. In this respect, it is worth noting that Paul Volcker is widely praised in policy circles for bringing down the inflation rate. To accomplish this goal he induced a recession that pushed the unemployment rate to almost 11 percent. So the idea that short-term pain might be a price worth paying for a longer term benefit is widely accepted in policy circles.

At one point the piece refers to the views of Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s finance minister, on the difficulties of leaving the euro. It relies on what it describes as a “recent blogpost.” Actually the post is from 2012.

To support the argument that Greece has little prospect for increasing its exports it quotes Daniel Gros, director of the Center for European Policy Studies in Brussels, on the impact of devaluation on tourism:

“But they’ve already cut prices and tourism has gone up. But it hasn’t really helped because total revenue hasn’t gone up.”

Actually tourism revenue has risen. It rose by 8.0 percent from 2011 to 2013 (the most recent data available) measured in euros and by roughly 20 percent measured in dollars. In arguing that Greece can’t increase revenue from fishing the piece tells readers:

“The European Union has strict quotas to prevent overfishing.”

However the piece also tells readers that leaving the euro would cause Greece to be thrown out of the European Union. If that’s true, the EU limits on fishing would be irrelevant.

The piece also make a big point of the fact that Greece does not at present have a currency other than the euro. There are plenty of countries, including many which are poorer than Greece, who have managed to switch over to a new currency in a relatively short period of time. While this process will never be painless, it must be compared to the pain associated with an indefinite period of unemployment in excess of 20.0 percent which is almost certainly the path associated with remaining in the euro on the Troika’s terms.

In making comparisons between Greece and Argentina, it is also worth noting that almost all economists projected disaster at the time Argentina defaulted in 2001. Perhaps they have learned more about economics in the last 14 years, but this is not obviously true.

Addendum

I should have also mentioned that the pre-default decline has been much sharper in Greece than in Argentina, over 25 percent in Greece, compared to less than 10.0 percent in Argentina. This should mean that Greece has much more room to bounce back if it regains control over its fiscal and monetary policy.

James Stewart has a piece in the NYT telling readers that if Greece were to leave the euro it would face a disaster. The headline warns readers, “imagine Argentina, but much worse.” The article includes several assertions that are misleading or false.

First, it is difficult to describe the default in Argentina as a disaster. The economy had been plummeting prior to the default, which occurred at the end of the year in 2001. The country’s GDP had actually fallen more before the default than it did after the default. (This is not entirely clear on the graph, since the data is annual. At the point where the default took place in December of 2001, Argentina’s GDP was already well below the year-round average.) While the economy did fall more sharply after the default, it soon rebounded and by the end of 2003 it had regained all the ground lost following the default.

Argentina’s economy continued to grow rapidly for several more years, rising above pre-recession levels in 2004. Given the fuller picture, it is difficult to see the default as an especially disastrous event even if it did lead to several months of uncertainty for the people of Argentina. In this respect, it is worth noting that Paul Volcker is widely praised in policy circles for bringing down the inflation rate. To accomplish this goal he induced a recession that pushed the unemployment rate to almost 11 percent. So the idea that short-term pain might be a price worth paying for a longer term benefit is widely accepted in policy circles.

At one point the piece refers to the views of Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s finance minister, on the difficulties of leaving the euro. It relies on what it describes as a “recent blogpost.” Actually the post is from 2012.

To support the argument that Greece has little prospect for increasing its exports it quotes Daniel Gros, director of the Center for European Policy Studies in Brussels, on the impact of devaluation on tourism:

“But they’ve already cut prices and tourism has gone up. But it hasn’t really helped because total revenue hasn’t gone up.”

Actually tourism revenue has risen. It rose by 8.0 percent from 2011 to 2013 (the most recent data available) measured in euros and by roughly 20 percent measured in dollars. In arguing that Greece can’t increase revenue from fishing the piece tells readers:

“The European Union has strict quotas to prevent overfishing.”

However the piece also tells readers that leaving the euro would cause Greece to be thrown out of the European Union. If that’s true, the EU limits on fishing would be irrelevant.

The piece also make a big point of the fact that Greece does not at present have a currency other than the euro. There are plenty of countries, including many which are poorer than Greece, who have managed to switch over to a new currency in a relatively short period of time. While this process will never be painless, it must be compared to the pain associated with an indefinite period of unemployment in excess of 20.0 percent which is almost certainly the path associated with remaining in the euro on the Troika’s terms.

In making comparisons between Greece and Argentina, it is also worth noting that almost all economists projected disaster at the time Argentina defaulted in 2001. Perhaps they have learned more about economics in the last 14 years, but this is not obviously true.

Addendum

I should have also mentioned that the pre-default decline has been much sharper in Greece than in Argentina, over 25 percent in Greece, compared to less than 10.0 percent in Argentina. This should mean that Greece has much more room to bounce back if it regains control over its fiscal and monetary policy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay, that may not have been the headline, but careful readers would see this is the case. The NYT ran a piece complaining that plans by the Greek government to raise business taxes, as opposed to further cuts to pensions and other spending, could hurt business.

The poster child for this argument is Thanos Tziritis, the owner of a family business that produces and exports a wide range of construction materials. The piece goes through the various complaints of Mr. Tziritis, at one point telling readers:

“Still, it took 20 months to get all the permissions and licenses to begin construction, as papers moved back and forth between Thessaloniki and Athens.

“One reason for the delay, Mr. Tziritis said he was told, was that one of the government employees examining the request was on maternity leave and no one else was authorized to look at that specific Isomat file. The project remained in limbo for more than six months until the civil servant returned to work.”

Presumably one of the reasons that no one else could fill in for the government employee examining the construction request was that Greece was forced to cut back on the number of employees. It may well be the case that Greece regulations are excessive, but until they are reformed cutting back on the number of people involved in the review process is likely to slow investment and growth, as this article indicates.

The article bizarrely implies that Greece has been resistant to making budget cuts, complaining:

“The I.M.F., in particular, is upset that its demands for spending reductions have been ignored.

“‘All expenditure measures have been replaced by taxes on capital and labor,’ said a fund official who spoke on the condition of anonymity. ‘This is very growth unfriendly.'”

In fact, total government spending has fallen by more than one-third since 2009, according to I.M.F. data.

It is also worth noting that, in violation on NYT policy, there is no reason given for why the fund official was granted anonymity.

Okay, that may not have been the headline, but careful readers would see this is the case. The NYT ran a piece complaining that plans by the Greek government to raise business taxes, as opposed to further cuts to pensions and other spending, could hurt business.

The poster child for this argument is Thanos Tziritis, the owner of a family business that produces and exports a wide range of construction materials. The piece goes through the various complaints of Mr. Tziritis, at one point telling readers:

“Still, it took 20 months to get all the permissions and licenses to begin construction, as papers moved back and forth between Thessaloniki and Athens.

“One reason for the delay, Mr. Tziritis said he was told, was that one of the government employees examining the request was on maternity leave and no one else was authorized to look at that specific Isomat file. The project remained in limbo for more than six months until the civil servant returned to work.”

Presumably one of the reasons that no one else could fill in for the government employee examining the construction request was that Greece was forced to cut back on the number of employees. It may well be the case that Greece regulations are excessive, but until they are reformed cutting back on the number of people involved in the review process is likely to slow investment and growth, as this article indicates.

The article bizarrely implies that Greece has been resistant to making budget cuts, complaining:

“The I.M.F., in particular, is upset that its demands for spending reductions have been ignored.

“‘All expenditure measures have been replaced by taxes on capital and labor,’ said a fund official who spoke on the condition of anonymity. ‘This is very growth unfriendly.'”

In fact, total government spending has fallen by more than one-third since 2009, according to I.M.F. data.

It is also worth noting that, in violation on NYT policy, there is no reason given for why the fund official was granted anonymity.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Michael Fletcher had a short piece highlighting the huge gulf in the economic status of whites and African Americans. While the piece rightly points out that there are no simple remedies to eliminate the gap, one of the charts suggests a policy that can make a huge difference.

The chart shows the overall unemployment rate and the unemployment rate for whites and African Americans. The unemployment rate for African Americans is consistently twice as high as the unemployment rate for whites. This means that a drop in the unemployment rate for whites of one percentage point would likely be associated with a drop of two percentage points in the unemployment rate for African Americans.

For African American teens the ratio is typically six to one. This means that a Federal Reserve Board policy of letting the unemployment rate fall as low as possible is likely to have large payoffs for African Americans, especially for young people trying to get a step up in the labor market. This may not eliminate the gap in status between whites and African Americans, but a commitment to a full employment policy may go a substantial distance in that direction.

Michael Fletcher had a short piece highlighting the huge gulf in the economic status of whites and African Americans. While the piece rightly points out that there are no simple remedies to eliminate the gap, one of the charts suggests a policy that can make a huge difference.

The chart shows the overall unemployment rate and the unemployment rate for whites and African Americans. The unemployment rate for African Americans is consistently twice as high as the unemployment rate for whites. This means that a drop in the unemployment rate for whites of one percentage point would likely be associated with a drop of two percentage points in the unemployment rate for African Americans.

For African American teens the ratio is typically six to one. This means that a Federal Reserve Board policy of letting the unemployment rate fall as low as possible is likely to have large payoffs for African Americans, especially for young people trying to get a step up in the labor market. This may not eliminate the gap in status between whites and African Americans, but a commitment to a full employment policy may go a substantial distance in that direction.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Emily Badger had an interesting discussion of the decline of homeownership in Wonkblog. However the piece neglected to mention one of the most important reasons why people might opt to rent rather than own: the insecurity of their employment situation.

It is usually not a good idea to spend the large overhead costs associated with buying a home unless you have a secure job where you can expect to stay many years into the future. As stable jobs become rarer in the economy (median job tenure has fallen sharply over the last three decades), homeownership is likely to make sense for a smaller segment of the population. If the trend towards shorter job tenure continues we should see further declines in the ownership rate in the years ahead.

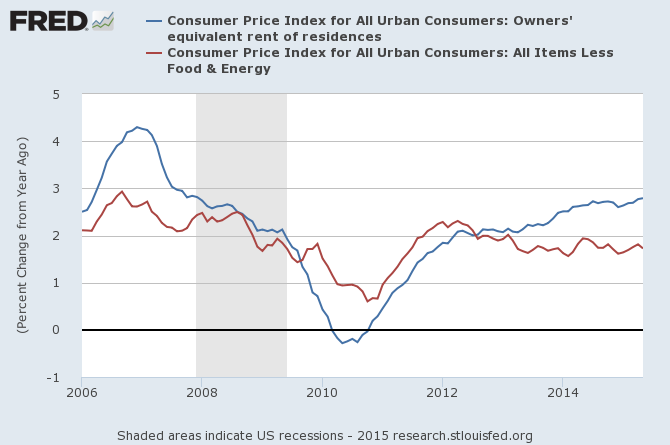

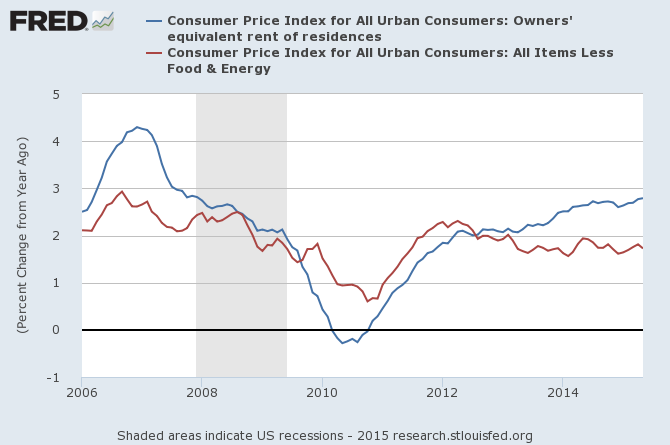

The piece also errors in implying that rental prices are rising substantially faster than other prices. For these sorts of comparisons it is best to use the owner equivalent rent (OER) measure, which pulls out utilities that are often included in the rent measure.

The graph shows that this measure of rent has somewhat outpaced core inflation over the last few years, but this followed several years in which OER rose less rapidly than the core rate of inflation. Since January of 2006, the OER has risen by 3.0 percentage points more than the core inflation rate.

Emily Badger had an interesting discussion of the decline of homeownership in Wonkblog. However the piece neglected to mention one of the most important reasons why people might opt to rent rather than own: the insecurity of their employment situation.

It is usually not a good idea to spend the large overhead costs associated with buying a home unless you have a secure job where you can expect to stay many years into the future. As stable jobs become rarer in the economy (median job tenure has fallen sharply over the last three decades), homeownership is likely to make sense for a smaller segment of the population. If the trend towards shorter job tenure continues we should see further declines in the ownership rate in the years ahead.

The piece also errors in implying that rental prices are rising substantially faster than other prices. For these sorts of comparisons it is best to use the owner equivalent rent (OER) measure, which pulls out utilities that are often included in the rent measure.

The graph shows that this measure of rent has somewhat outpaced core inflation over the last few years, but this followed several years in which OER rose less rapidly than the core rate of inflation. Since January of 2006, the OER has risen by 3.0 percentage points more than the core inflation rate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post ran a piece on Glenn Hubbard, the chief economic adviser to President George W. Bush and now an adviser to Jeb Bush, which ignored much of Mr. Hubbard’s history. For example, it told readers:

“Hubbard believes that for too long, the United States has only experienced rapid growth in the midst of what he calls ‘bubble economies,’ which don’t deliver broadly shared prosperity to workers. For example, he blames the Federal Reserve for stoking a bubble in the mid-2000s by keeping interest rates too low for too long.”

While the piece notes that Hubbard had been an adviser to Bush during part of this period, it neglects to tell readers that he never said anything about the housing bubble. In other words, Hubbard’s analysis is 100 percent hindsight, he completely missed the $8 trillion housing bubble, the collapse of which has devastated the economy.

He is also mistaken in claiming that bubbles cannot lead to “broadly shared prosperity to workers.” During the 1990s stock bubble, the unemployment rate eventually fell as low as 4.0 percent. During these years workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution saw healthy wage gains. The problem is that this growth could not be enduring, since it was based on a bubble.

It also would have been useful to remind readers that Hubbard had done excellent research indicating the Bush tax cuts would not be likely to have the promised effect of increasing investment. Hubbard’s research showed that investment is very unresponsive to reductions in the interest rate. The stated goal of tax cuts directed at high income households was to give them more incentive to save and thereby lower interest rates. If investment is unresponsive to a reduction in interest rates, then this is unlikely to be an effective route to boosting investment and growth.

Addendum:

My colleague, Nicholas Buffie, calls my attention to a paper that Professor Hubbard co-authored for Goldman Sach’s Global Markets Institute in 2004, near the peak of the bubble. The executive summary of the paper told readers:

“The ascendancy of the US capital markets — including increasing depth of US stock, bond, and derivative markets — has improved the allocation of capital and of risk throughout the US economy. Evidence includes the higher returns on capital in the US compared to elsewhere; the persistent, large inflows of capital to the US from abroad; the enhanced stability of the US banking system; and the ability of new companies to raise funds. The same conclusions apply to the United Kingdom, where the capital markets are also well-developed.” [emphasis added]

“The development of the capital markets has also facilitated a revolution in housing finance. As a result, the proportion of households in the US that own their homes has risen substantially over the past decade.”

“The capital markets have also acted to reduce the volatility of the economy. Recessions are less frequent and milder when they occur. As a result, upward spikes in the unemployment rate have occurred less frequently and have become less severe.”

The Washington Post ran a piece on Glenn Hubbard, the chief economic adviser to President George W. Bush and now an adviser to Jeb Bush, which ignored much of Mr. Hubbard’s history. For example, it told readers:

“Hubbard believes that for too long, the United States has only experienced rapid growth in the midst of what he calls ‘bubble economies,’ which don’t deliver broadly shared prosperity to workers. For example, he blames the Federal Reserve for stoking a bubble in the mid-2000s by keeping interest rates too low for too long.”

While the piece notes that Hubbard had been an adviser to Bush during part of this period, it neglects to tell readers that he never said anything about the housing bubble. In other words, Hubbard’s analysis is 100 percent hindsight, he completely missed the $8 trillion housing bubble, the collapse of which has devastated the economy.

He is also mistaken in claiming that bubbles cannot lead to “broadly shared prosperity to workers.” During the 1990s stock bubble, the unemployment rate eventually fell as low as 4.0 percent. During these years workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution saw healthy wage gains. The problem is that this growth could not be enduring, since it was based on a bubble.

It also would have been useful to remind readers that Hubbard had done excellent research indicating the Bush tax cuts would not be likely to have the promised effect of increasing investment. Hubbard’s research showed that investment is very unresponsive to reductions in the interest rate. The stated goal of tax cuts directed at high income households was to give them more incentive to save and thereby lower interest rates. If investment is unresponsive to a reduction in interest rates, then this is unlikely to be an effective route to boosting investment and growth.

Addendum:

My colleague, Nicholas Buffie, calls my attention to a paper that Professor Hubbard co-authored for Goldman Sach’s Global Markets Institute in 2004, near the peak of the bubble. The executive summary of the paper told readers:

“The ascendancy of the US capital markets — including increasing depth of US stock, bond, and derivative markets — has improved the allocation of capital and of risk throughout the US economy. Evidence includes the higher returns on capital in the US compared to elsewhere; the persistent, large inflows of capital to the US from abroad; the enhanced stability of the US banking system; and the ability of new companies to raise funds. The same conclusions apply to the United Kingdom, where the capital markets are also well-developed.” [emphasis added]

“The development of the capital markets has also facilitated a revolution in housing finance. As a result, the proportion of households in the US that own their homes has risen substantially over the past decade.”

“The capital markets have also acted to reduce the volatility of the economy. Recessions are less frequent and milder when they occur. As a result, upward spikes in the unemployment rate have occurred less frequently and have become less severe.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

An NYT article on the prospects of a deal between Greece and its creditors left this item off its list of the risks from Greece leaving the euro. If Greece were to leave the euro, its exports, most importantly tourism, would be hyper-competitive. This would likely lead to a huge increase in its business as travelers from Europe and the United States opt to visit Greece rather than other tourist destinations.

This could lead to the same sort of rebound that Iceland saw after its initial collapse. This would be hugely embarrassing to the I.M.F., the European Commission, and the European Central Bank, which have forced Greece to endure a depression and demand policies that will likely leave it with depression levels of unemployment for at least another decade.

This outcome will be especially painful for political leaders in countries like Spain and Portugal, both because they have imposed comparable depressions on their own populations and also because they will be directly hit by the loss of tourism to Greece. From their perspective, a successful Grexit would be the worst possible outcome.

An NYT article on the prospects of a deal between Greece and its creditors left this item off its list of the risks from Greece leaving the euro. If Greece were to leave the euro, its exports, most importantly tourism, would be hyper-competitive. This would likely lead to a huge increase in its business as travelers from Europe and the United States opt to visit Greece rather than other tourist destinations.

This could lead to the same sort of rebound that Iceland saw after its initial collapse. This would be hugely embarrassing to the I.M.F., the European Commission, and the European Central Bank, which have forced Greece to endure a depression and demand policies that will likely leave it with depression levels of unemployment for at least another decade.

This outcome will be especially painful for political leaders in countries like Spain and Portugal, both because they have imposed comparable depressions on their own populations and also because they will be directly hit by the loss of tourism to Greece. From their perspective, a successful Grexit would be the worst possible outcome.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a piece on efforts to encourage doctors to assess the price and relative effectiveness of drugs when writing prescriptions for cancer patients. It notes that drug companies charge $10,000-$30,000 a month for many of the new cancer drugs. It then comments on the suggestion that doctors should take these costs into account in deciding treatment:

“Evaluating the latter cost would put doctors in the role of being stewards of societal resources. That is somewhat of a controversial role for doctors, since it might conflict with their duty to the patient in front of them.”

It is important to note that doctors are not exactly in the role of deciding whether resources would be allocated to developing these cancer drugs, since that decision would have already been made. The resources devoted to developing the drugs have already been used at the point where doctors are deciding whether to prescribe them. The doctors’ decision only determines how much drug companies will profit as a result of committing these resources.

This is an important distinction. Obviously profits will affect the drug companies decisions on future research, but at the point where the drug exists, it costs society very little to make it available to every patient who would benefit. It is only due to patent monopolies that we get such a sharp divergence between the price facing the patient or insurer and the cost to society.

The NYT had a piece on efforts to encourage doctors to assess the price and relative effectiveness of drugs when writing prescriptions for cancer patients. It notes that drug companies charge $10,000-$30,000 a month for many of the new cancer drugs. It then comments on the suggestion that doctors should take these costs into account in deciding treatment:

“Evaluating the latter cost would put doctors in the role of being stewards of societal resources. That is somewhat of a controversial role for doctors, since it might conflict with their duty to the patient in front of them.”

It is important to note that doctors are not exactly in the role of deciding whether resources would be allocated to developing these cancer drugs, since that decision would have already been made. The resources devoted to developing the drugs have already been used at the point where doctors are deciding whether to prescribe them. The doctors’ decision only determines how much drug companies will profit as a result of committing these resources.

This is an important distinction. Obviously profits will affect the drug companies decisions on future research, but at the point where the drug exists, it costs society very little to make it available to every patient who would benefit. It is only due to patent monopolies that we get such a sharp divergence between the price facing the patient or insurer and the cost to society.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Wall Street Journal was good enough to give us “our entitlement problem for the next generation in one CBO chart.” The featured chart shows the projected discounted cost of Medicare benefits compared with the discounted value of the taxes paid in. It shows that the former is around three times the latter for the baby boom cohorts.

While this may look like the baby boomers are getting a real bonanza on their health care the real story is that the doctors and the drug companies are getting a real windfall at the expense of the rest of the country. Our health care providers earn roughly twice as much on average as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. There is little evidence they provide anything in the form of better service for this money, they just get much richer.

The doctors and other providers are able to largely limit domestic competition through their control of licensing and the setting of health care standards. They also obstruct any efforts to open up health care to international competition for example by allowing Medicare beneficiaries to buy into the health care systems of other countries (yes, this would have to be negotiated — sort of like the TPP) or by increasing the number of foreign trained doctors who practice in the United States.

Anyhow, if we paid the same per person amount for health care as people in other wealthy countries, most of the gap between the cost of Medicare and Medicare taxes would disappear. Therefore we can more accurately say this is a picture of our health care cost problem in one graph. The power of the health care providers makes it very difficult politically to fix this problem, but it should at least be possible to talk about it.

The Wall Street Journal was good enough to give us “our entitlement problem for the next generation in one CBO chart.” The featured chart shows the projected discounted cost of Medicare benefits compared with the discounted value of the taxes paid in. It shows that the former is around three times the latter for the baby boom cohorts.

While this may look like the baby boomers are getting a real bonanza on their health care the real story is that the doctors and the drug companies are getting a real windfall at the expense of the rest of the country. Our health care providers earn roughly twice as much on average as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. There is little evidence they provide anything in the form of better service for this money, they just get much richer.

The doctors and other providers are able to largely limit domestic competition through their control of licensing and the setting of health care standards. They also obstruct any efforts to open up health care to international competition for example by allowing Medicare beneficiaries to buy into the health care systems of other countries (yes, this would have to be negotiated — sort of like the TPP) or by increasing the number of foreign trained doctors who practice in the United States.

Anyhow, if we paid the same per person amount for health care as people in other wealthy countries, most of the gap between the cost of Medicare and Medicare taxes would disappear. Therefore we can more accurately say this is a picture of our health care cost problem in one graph. The power of the health care providers makes it very difficult politically to fix this problem, but it should at least be possible to talk about it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson used his column today to note the sharp rise in CEO pay. He ends up leaving it an open question as to whether the increase in the pay gap between CEOs and average workers, from an average of 20 to 1 in the 1960s to 300 to 1 at present, reflects the fundamentals of the market. In assessing this question, it is worth considering the incentives for the boards of directors that set CEO pay.

If a CEO wants another $1 million, a director is likely to make herself unpopular among her peers, many of whom are likely to be personal friends of the CEO, if she refuses to go along. Furthermore, if the CEO were to leave because they did not get the pay raise, and the company performed poorly (possibly because of random events having nothing to do with the CEO), the director who opposed the pay increase would be likely to see their position threatened.

On the other hand, directors almost never have their positions threatened as a result of overpaying their CEO. It is very difficult for disgruntled shareholders to organize to remove a director.

In this context, it would not be surprising if CEO pay continued to rise. With such asymmetric incentives, there is not the same sort of downward pressure on CEO pay as there is for auto workers or retail workers. Therefore, it should not be surprising that if gap in pay continues to increase.

Robert Samuelson used his column today to note the sharp rise in CEO pay. He ends up leaving it an open question as to whether the increase in the pay gap between CEOs and average workers, from an average of 20 to 1 in the 1960s to 300 to 1 at present, reflects the fundamentals of the market. In assessing this question, it is worth considering the incentives for the boards of directors that set CEO pay.

If a CEO wants another $1 million, a director is likely to make herself unpopular among her peers, many of whom are likely to be personal friends of the CEO, if she refuses to go along. Furthermore, if the CEO were to leave because they did not get the pay raise, and the company performed poorly (possibly because of random events having nothing to do with the CEO), the director who opposed the pay increase would be likely to see their position threatened.

On the other hand, directors almost never have their positions threatened as a result of overpaying their CEO. It is very difficult for disgruntled shareholders to organize to remove a director.

In this context, it would not be surprising if CEO pay continued to rise. With such asymmetric incentives, there is not the same sort of downward pressure on CEO pay as there is for auto workers or retail workers. Therefore, it should not be surprising that if gap in pay continues to increase.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión