There is a growing industry in the United States of people promoting stories about how robots and other technological innovations are going to make us all unemployed. Unfortunately Harold Meyerson seems to have taken these people seriously.

Meyerson cites a study showing that technology is likely to slash employment in large sectors of the economy and then tells readers:

“Eventually, however, as computers pick up more and more skills, we will have to embrace the necessity of redistributing wealth and income from the shrinking number of Americans who have sizable incomes from their investments or their work to the growing number of Americans who want work but can’t find it. That may or may not be socialism; certainly, it’s survival.”

The problem with this story is that it is 180 degrees at odds with the data. Robots and computers seem to fascinate people as something new and different, but actually they are just forms of productivity growth. The issue is simply one of how fast we might expect these new technologies to increase productivity and displace workers. The answer we have been getting to date from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is not very fast.

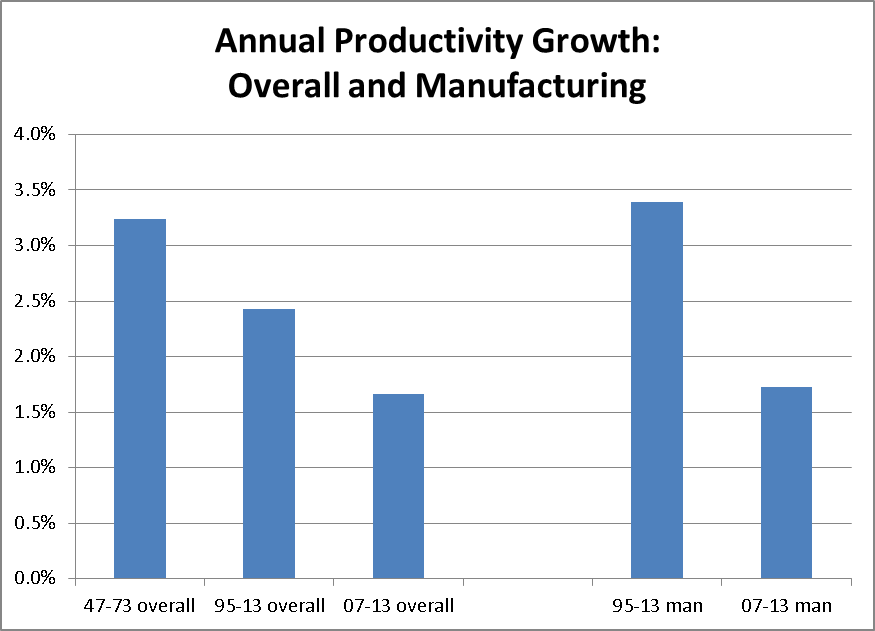

Here’s what the picture looks like from the latest data.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, the overall rate of productivity growth in the years since the speedup began in 1995 has been less than 2.4 percent annually. This compares to a rate of 3.2 percent in the years 1947-73, when unemployment was low and wage growth was strong. (Due to measurement issues such as the difference between gross and net output and differences in price indices, “usable” annual productivity growth was about 0.3 percentage points higher in the years 1947-73 relative to the official numbers.) In the more recent years since the downturn, productivity growth has fallen off to less than 1.7 percent annually.

If we look to manufacturing alone, there is a bit more of a story, but still not much. Productivity growth in the years since 1995 has averaged 3.4 percent, this is slightly higher than 3.2 percent overall rate of productivity growth in the 1947-1973. That can’t be enough to tell a qualitatively different story, especially since manufacturing now accounts for less than 10 percent of total employment. Furthermore manufacturing productivity growth was almost certainly stronger than overall productivity growth in the years 1947-73 golden age also (BLS does not give that series), so that would likely mean that it was faster than the rate we have seen in manufacturing since 1995. As with overall productivity, manufacturing productivity growth has also slowed sharply since 2007.

So why should we think that productivity growth will lead to a problem of too few jobs, as opposed to providing a basis for rising wages and living standards? if there is some huge productivity boom facing us in the near future, it is hiding pretty well from the folks gathering the data at BLS.

This is an important point because socialism or large-scale redistribution are big deals. We don’t expect that our politicians in Washington will be likely to embrace either concept any time soon. But much smaller and simpler policies can ensure that workers have jobs and share in the gains of economic growth. If we get the value of the dollar down against other currencies, we will reduce the trade deficit and create millions of jobs. President Obama could negotiate a decline in the value of the dollar against the currencies of our major trading partners as President Reagan did in the mid-1980s. We could also boost demand with increased stimulus and we could give more workers jobs through work sharing policies. (Read the book, it’s free.)

Anyhow, the point is that we are not in a brave new world where the basics of economics and technology are destined to screw the vast majority of workers absent major changes in public policy. We are in the vicious old world where the bad guys are actively manipulating public policy in ways that are screwing workers now. If we are going to make any headway in reversing this process we have to keep our eye on the ball.

There is a growing industry in the United States of people promoting stories about how robots and other technological innovations are going to make us all unemployed. Unfortunately Harold Meyerson seems to have taken these people seriously.

Meyerson cites a study showing that technology is likely to slash employment in large sectors of the economy and then tells readers:

“Eventually, however, as computers pick up more and more skills, we will have to embrace the necessity of redistributing wealth and income from the shrinking number of Americans who have sizable incomes from their investments or their work to the growing number of Americans who want work but can’t find it. That may or may not be socialism; certainly, it’s survival.”

The problem with this story is that it is 180 degrees at odds with the data. Robots and computers seem to fascinate people as something new and different, but actually they are just forms of productivity growth. The issue is simply one of how fast we might expect these new technologies to increase productivity and displace workers. The answer we have been getting to date from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is not very fast.

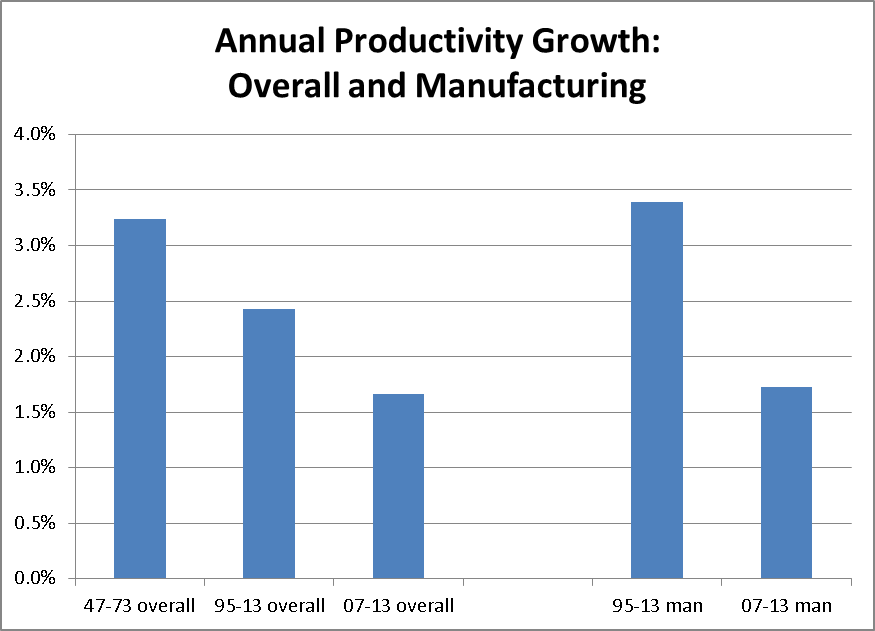

Here’s what the picture looks like from the latest data.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, the overall rate of productivity growth in the years since the speedup began in 1995 has been less than 2.4 percent annually. This compares to a rate of 3.2 percent in the years 1947-73, when unemployment was low and wage growth was strong. (Due to measurement issues such as the difference between gross and net output and differences in price indices, “usable” annual productivity growth was about 0.3 percentage points higher in the years 1947-73 relative to the official numbers.) In the more recent years since the downturn, productivity growth has fallen off to less than 1.7 percent annually.

If we look to manufacturing alone, there is a bit more of a story, but still not much. Productivity growth in the years since 1995 has averaged 3.4 percent, this is slightly higher than 3.2 percent overall rate of productivity growth in the 1947-1973. That can’t be enough to tell a qualitatively different story, especially since manufacturing now accounts for less than 10 percent of total employment. Furthermore manufacturing productivity growth was almost certainly stronger than overall productivity growth in the years 1947-73 golden age also (BLS does not give that series), so that would likely mean that it was faster than the rate we have seen in manufacturing since 1995. As with overall productivity, manufacturing productivity growth has also slowed sharply since 2007.

So why should we think that productivity growth will lead to a problem of too few jobs, as opposed to providing a basis for rising wages and living standards? if there is some huge productivity boom facing us in the near future, it is hiding pretty well from the folks gathering the data at BLS.

This is an important point because socialism or large-scale redistribution are big deals. We don’t expect that our politicians in Washington will be likely to embrace either concept any time soon. But much smaller and simpler policies can ensure that workers have jobs and share in the gains of economic growth. If we get the value of the dollar down against other currencies, we will reduce the trade deficit and create millions of jobs. President Obama could negotiate a decline in the value of the dollar against the currencies of our major trading partners as President Reagan did in the mid-1980s. We could also boost demand with increased stimulus and we could give more workers jobs through work sharing policies. (Read the book, it’s free.)

Anyhow, the point is that we are not in a brave new world where the basics of economics and technology are destined to screw the vast majority of workers absent major changes in public policy. We are in the vicious old world where the bad guys are actively manipulating public policy in ways that are screwing workers now. If we are going to make any headway in reversing this process we have to keep our eye on the ball.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’m not kidding on this. If you wanted proof that Republicans have zero interest in a free market and that most reporters are too thick to notice you couldn’t ask for a better example than Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal’s lawsuit against Moveon.org over billboards criticizing his decision not to extend Medicaid coverage in the state. As written up in a column by Katrina vanden Heuvel, the suit claims the billboards, which play off the state’s tourism slogan, “Pick Your Passion,” are causing damage to the state’s tourism promotion efforts by reducing the value of its copyrighted slogan.

Could someone who believes in a free market really want the U.S. government to prevent someone from taking out billboards because of the damages they impose on business? Obviously Jindal doesn’t give a damn about free markets, just like a person who runs a dog fighting ring doesn’t care about animal rights. Fortunately for Jindal, he lives in a country where the media’s definition of impartiality means that they cannot point out that a Republican who profits from dog fighting may not be committed to animal rights.

I’m not kidding on this. If you wanted proof that Republicans have zero interest in a free market and that most reporters are too thick to notice you couldn’t ask for a better example than Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal’s lawsuit against Moveon.org over billboards criticizing his decision not to extend Medicaid coverage in the state. As written up in a column by Katrina vanden Heuvel, the suit claims the billboards, which play off the state’s tourism slogan, “Pick Your Passion,” are causing damage to the state’s tourism promotion efforts by reducing the value of its copyrighted slogan.

Could someone who believes in a free market really want the U.S. government to prevent someone from taking out billboards because of the damages they impose on business? Obviously Jindal doesn’t give a damn about free markets, just like a person who runs a dog fighting ring doesn’t care about animal rights. Fortunately for Jindal, he lives in a country where the media’s definition of impartiality means that they cannot point out that a Republican who profits from dog fighting may not be committed to animal rights.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the question that readers of Fivethirtyeight Economics are asking after reading a discussion of the choices facing the Federal Reserve Board. The piece told readers that the Fed could push unemployment rate down to levels where inflation began to accelerate (overshooting):

“Overshooting is risky. The Fed would risk its credibility as an inflation-fighting central bank.”

The cost of keeping the unemployment rate up is that the government (through the Fed) is denying millions of people the opportunity to get jobs. The government is also putting downward pressure on the wages of the bottom half of the workforce, since their wages are especially sensitive to the unemployment rate. And the economy is losing hundreds of billions of dollars a year in lost output, since these workers could be productively employed.

Obviously Fivethirtyeight attaches great value to the Fed’s credibility as an inflation-fighting central bank since it thinks that we might think this value exceeds the costs of keeping the unemployment rate high. It would be helpful to readers if it explained how high this value is and how it came to this assessment.

That’s the question that readers of Fivethirtyeight Economics are asking after reading a discussion of the choices facing the Federal Reserve Board. The piece told readers that the Fed could push unemployment rate down to levels where inflation began to accelerate (overshooting):

“Overshooting is risky. The Fed would risk its credibility as an inflation-fighting central bank.”

The cost of keeping the unemployment rate up is that the government (through the Fed) is denying millions of people the opportunity to get jobs. The government is also putting downward pressure on the wages of the bottom half of the workforce, since their wages are especially sensitive to the unemployment rate. And the economy is losing hundreds of billions of dollars a year in lost output, since these workers could be productively employed.

Obviously Fivethirtyeight attaches great value to the Fed’s credibility as an inflation-fighting central bank since it thinks that we might think this value exceeds the costs of keeping the unemployment rate high. It would be helpful to readers if it explained how high this value is and how it came to this assessment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a good column on the government’s efforts to prevent people from buying lower cost drugs from foreign countries. The column makes the point that the Food and Drug Administration has misleadingly tried to claim that the issue with foreign drugs is one of safety when it really is just pharmaceutical industry profits. If people know that they can buy drugs for prices that are often less than one fifth the price in the United States, they will be unlikely to buy the drugs in the United States.

The government has therefore tried to prevent lower cost drugs from entering the country. It also uses trade agreements like the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership to raise drug prices in other countries. This both increases industry profits overseas and removes a potential source of low cost drugs.

Low cost drugs do undermine the usefulness of patent protection as a way to finance research and development, just as black markets in blue jeans undermined central planning in the Soviet Union. Ordinarily economists look to mechanisms that are consistent with markets rather than ones that depend on stifling markets. For some reason economists have shown little interest in any of the alternatives to patents, such as public funding through entities like the NIH, as ways to finance prescription drug research. Since these alternatives could bring patent protected drug prices down by 80-90 percent, they would offer enormous economic gains, in addition to the obvious benefits to public health.

The NYT had a good column on the government’s efforts to prevent people from buying lower cost drugs from foreign countries. The column makes the point that the Food and Drug Administration has misleadingly tried to claim that the issue with foreign drugs is one of safety when it really is just pharmaceutical industry profits. If people know that they can buy drugs for prices that are often less than one fifth the price in the United States, they will be unlikely to buy the drugs in the United States.

The government has therefore tried to prevent lower cost drugs from entering the country. It also uses trade agreements like the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership to raise drug prices in other countries. This both increases industry profits overseas and removes a potential source of low cost drugs.

Low cost drugs do undermine the usefulness of patent protection as a way to finance research and development, just as black markets in blue jeans undermined central planning in the Soviet Union. Ordinarily economists look to mechanisms that are consistent with markets rather than ones that depend on stifling markets. For some reason economists have shown little interest in any of the alternatives to patents, such as public funding through entities like the NIH, as ways to finance prescription drug research. Since these alternatives could bring patent protected drug prices down by 80-90 percent, they would offer enormous economic gains, in addition to the obvious benefits to public health.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post columnist Marc Theissen speculates on why Paul Ryan’s critics are so unhappy with his recent writings and speeches on poverty:

“Why are Democrats so threatened by a Republican congressman trying to find new ways to help the poor and vulnerable? Wouldn’t it be better if there were two parties competing to find the best ways to alleviate poverty?”

Maybe part of the reason is that Ryan didn’t actually present any new ideas. Everything in his bag of tricks is at least two decades old and in many cases much older. Furthermore, much of his analysis was based on misrepresentations of research on poverty.

Is it really surprising that people who are concerned about addressing the plight of the poor are upset when an ambitious politician seems to deliberately misrepresent decades of research by serious scholars in order to push his political agenda? The fact that these misrepresentations get large amounts of media attention, when the actual research is largely ignored, is a further cause for anger.

Washington Post columnist Marc Theissen speculates on why Paul Ryan’s critics are so unhappy with his recent writings and speeches on poverty:

“Why are Democrats so threatened by a Republican congressman trying to find new ways to help the poor and vulnerable? Wouldn’t it be better if there were two parties competing to find the best ways to alleviate poverty?”

Maybe part of the reason is that Ryan didn’t actually present any new ideas. Everything in his bag of tricks is at least two decades old and in many cases much older. Furthermore, much of his analysis was based on misrepresentations of research on poverty.

Is it really surprising that people who are concerned about addressing the plight of the poor are upset when an ambitious politician seems to deliberately misrepresent decades of research by serious scholars in order to push his political agenda? The fact that these misrepresentations get large amounts of media attention, when the actual research is largely ignored, is a further cause for anger.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This was one of the main points of a column that Andy Puzder, the CEO of Hardee’s parent company CKE Restaurants, made in a WSJ column today. The column was complaining over President Obama’s decision to raise the salary floor where overtime rules in the Fair Labor Standards Act (FSLA) may not apply. The current floor is $24,000 a year. Anyone getting lower pay than this is automatically covered by the FSLA overtime provisions.

Puzder is concerned that many of his branch managers will be covered by the FSLA overtime rules under the new floor that Obama will set. He tells readers that his managers start at around $36,000 a year and as high as $65,000, with an average around $45,000.

If the minimum wage had kept pace with economy-wide productivity growth since 1968 it would be over $17 an hour today. This means that, at $18 an hour, Hardee’s entry level pay for the people it calls managers would be just slightly above a productivity adjusted minimum wage. And this calculation assumes that it managers put in just 40 hours a week. If they typically put in more hours than they would likely be earning less than 1968 minimum wage, adjusted for productivity growth.

This was one of the main points of a column that Andy Puzder, the CEO of Hardee’s parent company CKE Restaurants, made in a WSJ column today. The column was complaining over President Obama’s decision to raise the salary floor where overtime rules in the Fair Labor Standards Act (FSLA) may not apply. The current floor is $24,000 a year. Anyone getting lower pay than this is automatically covered by the FSLA overtime provisions.

Puzder is concerned that many of his branch managers will be covered by the FSLA overtime rules under the new floor that Obama will set. He tells readers that his managers start at around $36,000 a year and as high as $65,000, with an average around $45,000.

If the minimum wage had kept pace with economy-wide productivity growth since 1968 it would be over $17 an hour today. This means that, at $18 an hour, Hardee’s entry level pay for the people it calls managers would be just slightly above a productivity adjusted minimum wage. And this calculation assumes that it managers put in just 40 hours a week. If they typically put in more hours than they would likely be earning less than 1968 minimum wage, adjusted for productivity growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That what readers of Andrew Sorkin’s column on management bonuses at Coca-Cola will be asking. Sorkin cites analysis from money manager David Winters showing that Coca-Cola has set aside $24 billion as bonuses for senior management in recent years. The 2013 set asides alone came to an average of more than $2 million for each eligible person.

Richard M. Daley is a director of Coca-Cola. As a director it is his job to make sure that management does not rip off shareholders by paying themselves excessive salaries. He was paid almost $180,000 last year for his work as a director. People may be asking now what exactly he did for this money.

That what readers of Andrew Sorkin’s column on management bonuses at Coca-Cola will be asking. Sorkin cites analysis from money manager David Winters showing that Coca-Cola has set aside $24 billion as bonuses for senior management in recent years. The 2013 set asides alone came to an average of more than $2 million for each eligible person.

Richard M. Daley is a director of Coca-Cola. As a director it is his job to make sure that management does not rip off shareholders by paying themselves excessive salaries. He was paid almost $180,000 last year for his work as a director. People may be asking now what exactly he did for this money.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Brad DeLong and Paul Krugman are having some back and forth on the problem of secular stagnation and what it would have taken to avoid a prolonged period of high unemployment. I thought I would weigh in quickly since I have a better track record on this stuff than either of them.

The basic story going into the crash was that we had an economy that was being driven by the housing bubble. This was both directly through residential construction and indirectly through the consumption that followed from $8 trillion of bubble generated housing equity. Residential construction expanded to a record high of more than 6 percent of GDP at a time when demographics would have implied its share would be shrinking. This led to enormous overbuilding, which is why construction hit record lows following the crash. (There was a smaller bubble in non-residential real estate that also burst in the crash.)

Consumption also predictably plummeted. This is known as the housing wealth effect. (I learned about this in grad school, didn’t anyone else?) Anyhow, when people saw their homes soar in value many spent in part based on this wealth. This might have meant doing cash out refinancing, a story that obsessed Alan Greenspan during the bubble years. It might mean a home equity loan, or it might just mean not putting money into a retirement account because your house is saving for you.

In any case, when the $8 trillion in bubble generated equity disappeared so did the consumption that it was driving. You can’t borrow against equity that isn’t there. This cost the economy between $400 billion and $600 billion (@ 3-4 percent of GDP) in annual consumption expenditures. Between the lost construction and lost consumption, it was necessary to replace close to 8 percent of GDP. The effect of lost tax revenue in forcing cutbacks at the state and local level raised the demand loss by another percentage point or so.

Some of this gap would be filled as excess inventory of housing gradually faded and the vacancy rates came back to more normal levels. We’re getting there, but still have some way to go. Some would be filled by a drop in the trade deficit, which now sits at around 3 percent of GDP, compared to a level of almost 6 percent of GDP before the crisis.

The government could fill the remaining gap with additional spending, but our cult of low-deficit politicians is insisting that they would rather keep people from getting jobs, so this ain’t going to happen. Low interest rates are of course a good route to spark demand, and if we could lower real rates further with a higher inflation rate, that would be good news. But that one also doesn’t seem very promising.

The other part of the demand story would be to make more progress on the trade deficit. This one is not rocket science, a lower dollar means a lower trade deficit (more econ 101). The issue of lowering the dollar is often posed as a matter of getting tough with the Chinese and force them to stop “manipulating” their currency.

We actually don’t have to hide in the dark and wait to catch China in the act and then bring them to justice. China very openly maintains its currency at a level that is well below the market rate. They set a target for their exchange rate and they maintain it by buying up massive amount of foreign assets, such as U.S. government bonds. We don’t have to catch them in the act, all of this is completely open and involves trillions of dollars of asset purchases.

It is also not a matter of bringing China to justice over the issue. China has found maintaining an under-valued currency to be a useful development strategy, but they also find other policies to be useful to their development strategy, like not enforcing foreign patent and copyrights or not opening their financial markets to companies like Goldman Sachs.

This suggests an obvious path for getting China to allow the dollar to fall against its currency. We simply tell them that we don’t care if they enforce Pfizer and Merck’s patents or Microsoft’s copyrights. We also tell them they don’t have to open up their financial markets to Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan and the other Wall Street behemoths, we just want them to raise the value of their currency.

Again, this path may not be politically viable either because of the relative power of the drug companies and banks as opposed to tens of millions of unemployed and under-employed workers, but let’s at least get the cards on the table. As fans of national income accounting everywhere know, we will not be able to get to potential GDP without large budget deficits as long as we have large trade deficits (assuming no more bubbles).

There is one other item that must be on the full employment agenda especially as we approach the big March 31 deadline for Obamacare. If we reduce the supply of labor we can also get to full employment. Obamacare will be a useful step in this direction since it will give millions of workers the option not to work or to work fewer hours since they will not have to get health insurance through their jobs. This means that parents of young children will be able to spend more time with their kids, people suffering from illnesses or disabilities will be able to rest more and work less, and many older workers will be able to retire early.

There are other ways we can go to accommodate people’s needs and thereby reduce the labor supply. For example more paid sick days would be good news, as would be paid family and medical leave. Many state and local governments are leading the way in these areas. Also, some paid vacation would be nice. Four weeks has been the norm in Europe for decades with some countries guaranteeing as much as six weeks of paid vacation. (Yep, it’s all in the good book.)

Anyhow, there are always things that can be done. The key point is to first understand where we are. And the most important take away is that millions are suffering now not because we are too poor, but we are too rich. We don’t need all the workers we have. This provides enormous opportunities for making people’s lives better, if we just had the political will.

Brad DeLong and Paul Krugman are having some back and forth on the problem of secular stagnation and what it would have taken to avoid a prolonged period of high unemployment. I thought I would weigh in quickly since I have a better track record on this stuff than either of them.

The basic story going into the crash was that we had an economy that was being driven by the housing bubble. This was both directly through residential construction and indirectly through the consumption that followed from $8 trillion of bubble generated housing equity. Residential construction expanded to a record high of more than 6 percent of GDP at a time when demographics would have implied its share would be shrinking. This led to enormous overbuilding, which is why construction hit record lows following the crash. (There was a smaller bubble in non-residential real estate that also burst in the crash.)

Consumption also predictably plummeted. This is known as the housing wealth effect. (I learned about this in grad school, didn’t anyone else?) Anyhow, when people saw their homes soar in value many spent in part based on this wealth. This might have meant doing cash out refinancing, a story that obsessed Alan Greenspan during the bubble years. It might mean a home equity loan, or it might just mean not putting money into a retirement account because your house is saving for you.

In any case, when the $8 trillion in bubble generated equity disappeared so did the consumption that it was driving. You can’t borrow against equity that isn’t there. This cost the economy between $400 billion and $600 billion (@ 3-4 percent of GDP) in annual consumption expenditures. Between the lost construction and lost consumption, it was necessary to replace close to 8 percent of GDP. The effect of lost tax revenue in forcing cutbacks at the state and local level raised the demand loss by another percentage point or so.

Some of this gap would be filled as excess inventory of housing gradually faded and the vacancy rates came back to more normal levels. We’re getting there, but still have some way to go. Some would be filled by a drop in the trade deficit, which now sits at around 3 percent of GDP, compared to a level of almost 6 percent of GDP before the crisis.

The government could fill the remaining gap with additional spending, but our cult of low-deficit politicians is insisting that they would rather keep people from getting jobs, so this ain’t going to happen. Low interest rates are of course a good route to spark demand, and if we could lower real rates further with a higher inflation rate, that would be good news. But that one also doesn’t seem very promising.

The other part of the demand story would be to make more progress on the trade deficit. This one is not rocket science, a lower dollar means a lower trade deficit (more econ 101). The issue of lowering the dollar is often posed as a matter of getting tough with the Chinese and force them to stop “manipulating” their currency.

We actually don’t have to hide in the dark and wait to catch China in the act and then bring them to justice. China very openly maintains its currency at a level that is well below the market rate. They set a target for their exchange rate and they maintain it by buying up massive amount of foreign assets, such as U.S. government bonds. We don’t have to catch them in the act, all of this is completely open and involves trillions of dollars of asset purchases.

It is also not a matter of bringing China to justice over the issue. China has found maintaining an under-valued currency to be a useful development strategy, but they also find other policies to be useful to their development strategy, like not enforcing foreign patent and copyrights or not opening their financial markets to companies like Goldman Sachs.

This suggests an obvious path for getting China to allow the dollar to fall against its currency. We simply tell them that we don’t care if they enforce Pfizer and Merck’s patents or Microsoft’s copyrights. We also tell them they don’t have to open up their financial markets to Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan and the other Wall Street behemoths, we just want them to raise the value of their currency.

Again, this path may not be politically viable either because of the relative power of the drug companies and banks as opposed to tens of millions of unemployed and under-employed workers, but let’s at least get the cards on the table. As fans of national income accounting everywhere know, we will not be able to get to potential GDP without large budget deficits as long as we have large trade deficits (assuming no more bubbles).

There is one other item that must be on the full employment agenda especially as we approach the big March 31 deadline for Obamacare. If we reduce the supply of labor we can also get to full employment. Obamacare will be a useful step in this direction since it will give millions of workers the option not to work or to work fewer hours since they will not have to get health insurance through their jobs. This means that parents of young children will be able to spend more time with their kids, people suffering from illnesses or disabilities will be able to rest more and work less, and many older workers will be able to retire early.

There are other ways we can go to accommodate people’s needs and thereby reduce the labor supply. For example more paid sick days would be good news, as would be paid family and medical leave. Many state and local governments are leading the way in these areas. Also, some paid vacation would be nice. Four weeks has been the norm in Europe for decades with some countries guaranteeing as much as six weeks of paid vacation. (Yep, it’s all in the good book.)

Anyhow, there are always things that can be done. The key point is to first understand where we are. And the most important take away is that millions are suffering now not because we are too poor, but we are too rich. We don’t need all the workers we have. This provides enormous opportunities for making people’s lives better, if we just had the political will.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had a major piece that discussed the ethics of efforts to use public pressure to force drug companies to make expensive drugs available to patients at affordable prices. Remarkably it never discussed the role of patent monopolies.

In the case that was the immediate focus of the article, a young boy who was suffering from cancer and seemed likely to benefit from a drug that was still in the experimental stage, it does not appear that patent protection was a major factor. However in many cases patients will face exorbitant prices for a life-saving drug that they may not be able to afford because the drug is subject to patent protection.

In such cases it is the patent that creates the moral dilemma raised in this article. If the drug were sold at its free market price it would likely be affordable to most patients. This is one of the perversities of patent financed drug research. While drugs can be expensive to develop, they are generally cheap to manufacture. It would be desirable for drugs to be sold at their free market price if some alternative mechanism (e.g. NIH funding) could be used to finance their development.

It would have been useful if this piece had discussed the way in which the mechanism we use to finance drug research can lead to the sort of ethical dilemmas it discusses. In this context it is probably worth mentioning that the Washington Post gets considerable revenue from drug company advertising.

Note: Typos corrected, thanks Robert Salzberg.

The Washington Post had a major piece that discussed the ethics of efforts to use public pressure to force drug companies to make expensive drugs available to patients at affordable prices. Remarkably it never discussed the role of patent monopolies.

In the case that was the immediate focus of the article, a young boy who was suffering from cancer and seemed likely to benefit from a drug that was still in the experimental stage, it does not appear that patent protection was a major factor. However in many cases patients will face exorbitant prices for a life-saving drug that they may not be able to afford because the drug is subject to patent protection.

In such cases it is the patent that creates the moral dilemma raised in this article. If the drug were sold at its free market price it would likely be affordable to most patients. This is one of the perversities of patent financed drug research. While drugs can be expensive to develop, they are generally cheap to manufacture. It would be desirable for drugs to be sold at their free market price if some alternative mechanism (e.g. NIH funding) could be used to finance their development.

It would have been useful if this piece had discussed the way in which the mechanism we use to finance drug research can lead to the sort of ethical dilemmas it discusses. In this context it is probably worth mentioning that the Washington Post gets considerable revenue from drug company advertising.

Note: Typos corrected, thanks Robert Salzberg.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In his column “when the scientist is also a philosopher,” Greg Mankiw tells us about his preference for not having the government interfere in consensual exchanges between individuals. He warns readers that economists who advocate such interventions also have a political philosophy about achieving certain outcomes (i.e. less inequality).

The wisdom of not interfering with consensual exchanges implies that is possible to have exchanges in which the government has not already played a huge role in setting the terms of the exchange. This is clearly not true.

For example, the number of jobs is very directly determined by government policy. We would have millions more jobs in the economy today if the government had not decided to run a high unemployment policy by reducing the size of the budget deficit. One can argue for the merits of deficit reduction, but this was a political choice where a lower deficit number was judged to be more important than letting millions of people have jobs.

In the same vein, we could have pursued policies to get the trade deficit closer to balance. If we had emphasized reducing the value of the dollar in our negotiations with trading partners, instead of things like patent protection for prescription drugs, copyright protection for Microsoft and Hollywood, and access to financial markets for Goldman Sachs, we would also have millions more people employed.

Furthermore, we could have structured trade agreements to put our doctors and lawyers in direct competition with their counterparts in the developing world (who would train to our standards) then globalization would not have been a factor increasing inequality. Instead it would have brought down the wages of the most highly skilled workers, while producing huge economic gains by lowering the cost of health care and other services. This would also have improved the bargaining situation of most of the workforce at the expense of business.

Mankiw is misleading readers by implying that we have the option to have consensual exchanges that are not shaped in very large ways by the government. (This is the topic of my free book, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.) In the last three decades, most of that shaping has been done to redistribute income upward.

In his column “when the scientist is also a philosopher,” Greg Mankiw tells us about his preference for not having the government interfere in consensual exchanges between individuals. He warns readers that economists who advocate such interventions also have a political philosophy about achieving certain outcomes (i.e. less inequality).

The wisdom of not interfering with consensual exchanges implies that is possible to have exchanges in which the government has not already played a huge role in setting the terms of the exchange. This is clearly not true.

For example, the number of jobs is very directly determined by government policy. We would have millions more jobs in the economy today if the government had not decided to run a high unemployment policy by reducing the size of the budget deficit. One can argue for the merits of deficit reduction, but this was a political choice where a lower deficit number was judged to be more important than letting millions of people have jobs.

In the same vein, we could have pursued policies to get the trade deficit closer to balance. If we had emphasized reducing the value of the dollar in our negotiations with trading partners, instead of things like patent protection for prescription drugs, copyright protection for Microsoft and Hollywood, and access to financial markets for Goldman Sachs, we would also have millions more people employed.

Furthermore, we could have structured trade agreements to put our doctors and lawyers in direct competition with their counterparts in the developing world (who would train to our standards) then globalization would not have been a factor increasing inequality. Instead it would have brought down the wages of the most highly skilled workers, while producing huge economic gains by lowering the cost of health care and other services. This would also have improved the bargaining situation of most of the workforce at the expense of business.

Mankiw is misleading readers by implying that we have the option to have consensual exchanges that are not shaped in very large ways by the government. (This is the topic of my free book, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.) In the last three decades, most of that shaping has been done to redistribute income upward.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión