That’s just in case you are like the vast majority of New York Times readers and have no clue how much $6 billion is. New York Times reporters do not have the ten seconds it takes to go to CEPR’s Responsible Budget Reporting calculator and make their stories informative to readers.

That’s just in case you are like the vast majority of New York Times readers and have no clue how much $6 billion is. New York Times reporters do not have the ten seconds it takes to go to CEPR’s Responsible Budget Reporting calculator and make their stories informative to readers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Many people who should know better have been placing far too much emphasis on the weather as an explanation for weak economic data. Cold weather and snow do slow economic activity as people don’t like to go shopping or to restaurants in sub-zero weather or blizzards. But cold weather and snow are normal parts of a winter in the Northeast-Midwest. This means their impact is already included in the seasonal adjustment factors for December and January.

The weather will only have an impact on the data if this winter is notably worse than recent winters. I’m not a meteorologist, but that doesn’t seem so obviously the case to me. In other words, it’s not clear that the weather has had much impact on the data we have been seeing.

I’ll also add that it’s hard to understand the claim from Ian Shepardson that with last year’s seasonal adjustment factors (these change slightly year to year), we would have seen 265,000 jobs rather than the 113,000 reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In the unadjusted data BLS showed a loss of 2,870,000 this year from December to January compared to a loss of 2,864,000 last year. Last January’s seasonally adjusted jobs number was 197,000.

Given the difference in the unadjusted numbers, at first glance that would look like we would have seasonally adjusted growth of 191,000 using last year’s factors. The actual number will not be simply additive because of differences in seasonal factors across sectors. Still is it hard to believe these differences would get us another 74,000 jobs.

Of course what seasonal factors give, they also take away. (On average, seasonal adjustments have to be zero.) In the seasonally adjusted data we created 149,000 fewer jobs in December of 2013 than in December of 2012. In the unadjusted data the difference was 194,000. If we want to say that we have the wrong seasonal factors so we should be happier about the January numbers, then we would have be more unhappy about weak December numbers.

Many people who should know better have been placing far too much emphasis on the weather as an explanation for weak economic data. Cold weather and snow do slow economic activity as people don’t like to go shopping or to restaurants in sub-zero weather or blizzards. But cold weather and snow are normal parts of a winter in the Northeast-Midwest. This means their impact is already included in the seasonal adjustment factors for December and January.

The weather will only have an impact on the data if this winter is notably worse than recent winters. I’m not a meteorologist, but that doesn’t seem so obviously the case to me. In other words, it’s not clear that the weather has had much impact on the data we have been seeing.

I’ll also add that it’s hard to understand the claim from Ian Shepardson that with last year’s seasonal adjustment factors (these change slightly year to year), we would have seen 265,000 jobs rather than the 113,000 reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In the unadjusted data BLS showed a loss of 2,870,000 this year from December to January compared to a loss of 2,864,000 last year. Last January’s seasonally adjusted jobs number was 197,000.

Given the difference in the unadjusted numbers, at first glance that would look like we would have seasonally adjusted growth of 191,000 using last year’s factors. The actual number will not be simply additive because of differences in seasonal factors across sectors. Still is it hard to believe these differences would get us another 74,000 jobs.

Of course what seasonal factors give, they also take away. (On average, seasonal adjustments have to be zero.) In the seasonally adjusted data we created 149,000 fewer jobs in December of 2013 than in December of 2012. In the unadjusted data the difference was 194,000. If we want to say that we have the wrong seasonal factors so we should be happier about the January numbers, then we would have be more unhappy about weak December numbers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

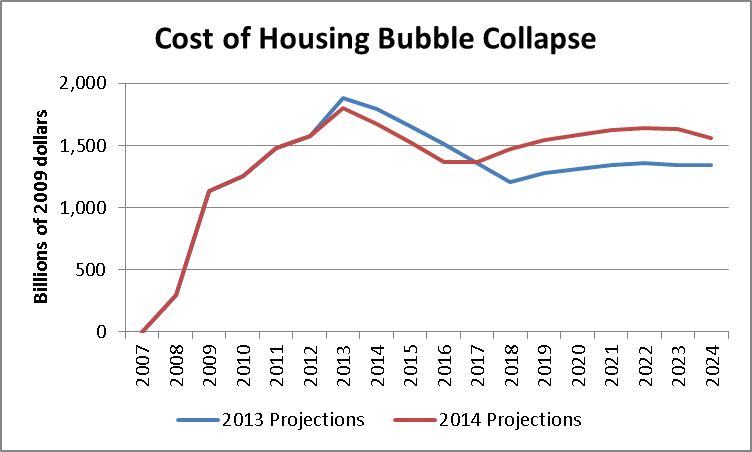

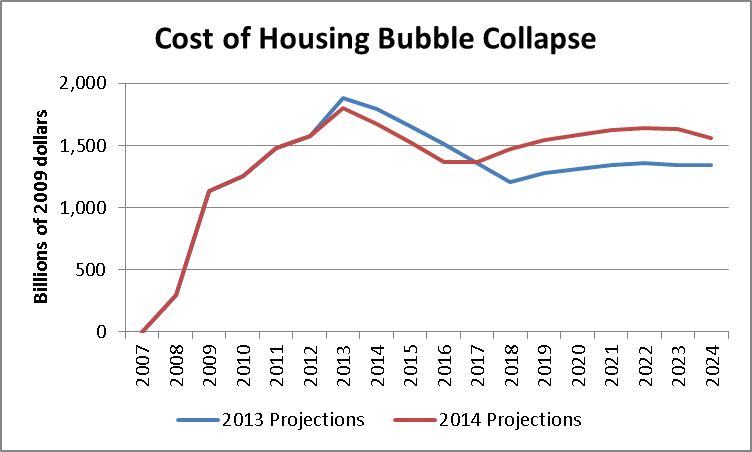

While the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projections of the impact of the Affordable Care Act got the most attention after the release of its new Budget and Economic Outlook, CBO also implicitly raised its estimate of the cost of the crisis created by the collapse of the housing bubble by $1.4 trillion. This is due to the fact that it downgraded its growth projections for later in the decade, for reasons unrelated to the ACA, with the view that more of the impact of the downturn will be enduring long into the future.

The figure below shows the difference between the 2008 projections for annual GDP and the projections from both the 2013 Outlook and the 2014 Outlook. The calculations use CBO’s Long-Term Budget Projections for years beyond the budget horizon. The 2014 projections for GDP are adjusted upward for the negative impact that CBO expects the ACA to have on GDP. The 2014 figure is accordingly raised by 0.5 percent from the CBO projection, the 2015 figure is raised by 0.75 percent, and subsequent years by 1.0 percent. (In effect, these projections assume that policy changes other than the ACA have had a neutral effect on growth.)

The cumulative cost of the collapse through the 2024 budget horizon, measured as a gap between projected output in 2008 and the most recent projections, is now $24.6 trillion, as shown below. This is equal to $80,000 for every person in the United States.

Source: CBO and author’s calculations.

While the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projections of the impact of the Affordable Care Act got the most attention after the release of its new Budget and Economic Outlook, CBO also implicitly raised its estimate of the cost of the crisis created by the collapse of the housing bubble by $1.4 trillion. This is due to the fact that it downgraded its growth projections for later in the decade, for reasons unrelated to the ACA, with the view that more of the impact of the downturn will be enduring long into the future.

The figure below shows the difference between the 2008 projections for annual GDP and the projections from both the 2013 Outlook and the 2014 Outlook. The calculations use CBO’s Long-Term Budget Projections for years beyond the budget horizon. The 2014 projections for GDP are adjusted upward for the negative impact that CBO expects the ACA to have on GDP. The 2014 figure is accordingly raised by 0.5 percent from the CBO projection, the 2015 figure is raised by 0.75 percent, and subsequent years by 1.0 percent. (In effect, these projections assume that policy changes other than the ACA have had a neutral effect on growth.)

The cumulative cost of the collapse through the 2024 budget horizon, measured as a gap between projected output in 2008 and the most recent projections, is now $24.6 trillion, as shown below. This is equal to $80,000 for every person in the United States.

Source: CBO and author’s calculations.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is what readers of a piece discussing President Obama’s shift in emphasis from the word “inequality” to “opportunity” will undoubtedly think. The piece notes that President Obama is using the word “opportunity” more and downplaying talk of inequality. It presents comments from several people saying that “inequality” raises the specter of class war and that it eliminates the possibility of compromise with Republicans.

Incredibly the piece presents the Republicans’ official line uncritically, telling readers:

“Republicans generally argue that government should do little; a free market and a growing economy will create opportunity. Their ideas to overhaul education, job-training and safety-net programs often double as budget-cutting initiatives.”

Of course Republicans argue that the government should do lots of things to redistribute income upward, they just don’t highlight the fact that the government is doing these things. For example, they are strong supporters of government granted patent monopolies that increase drug prices by close to $300 billion a year, an amount that is roughly equal to 1.8 percent of GDP and almost four times the SNAP budget. They support keeping in place the protectionist measures that largely insulate doctors and lawyers and other highly paid professionals from the same sort of international competition faced by autoworkers and textile workers.

Republicans support keeping in place a tax code that is littered with tax breaks, the exploitation of which is the primary basis for the existence of the private equity industry. (See my colleague Eileen Appelbaum’s forthcoming book on this topic.) Republicans support a special exemption of the financial industry from the sort of taxes that apply to other industries. This implicitly means higher taxes on other sectors of the economy and allows people to get ridiculously rich in finance. And they support a budget policy that keep millions of people out of work and puts downward pressure on the wages of most workers.

In short, it is absurd to say that the Republicans want the government to do little; they want the government to intervene in huge ways to redistribute income upward. Of course they don’t openly say this, they would much rather pretend that all the policies they support that lead to an upward redistribution of income are just the natural workings of the market. In this way, the NYT has done them a great service in uncritically projecting the Republicans’ romanticized image to readers as reflecting reality. However this completely distorts the relevant issues at play.

The real question is whether either party is prepared to attack the policies that have shifted such a vast amount of income upward over the last three decades. For practical purposes, if these policies are not changed, the agenda on mobility is just silly happy talk and everyone knows it. If the current policies promoting inequality are left in place there is nothing that Washington can do that can affect in more than a trivial way the life prospects of those in the bottom half and especially the bottom quintile of the income distribution.

That is what readers of a piece discussing President Obama’s shift in emphasis from the word “inequality” to “opportunity” will undoubtedly think. The piece notes that President Obama is using the word “opportunity” more and downplaying talk of inequality. It presents comments from several people saying that “inequality” raises the specter of class war and that it eliminates the possibility of compromise with Republicans.

Incredibly the piece presents the Republicans’ official line uncritically, telling readers:

“Republicans generally argue that government should do little; a free market and a growing economy will create opportunity. Their ideas to overhaul education, job-training and safety-net programs often double as budget-cutting initiatives.”

Of course Republicans argue that the government should do lots of things to redistribute income upward, they just don’t highlight the fact that the government is doing these things. For example, they are strong supporters of government granted patent monopolies that increase drug prices by close to $300 billion a year, an amount that is roughly equal to 1.8 percent of GDP and almost four times the SNAP budget. They support keeping in place the protectionist measures that largely insulate doctors and lawyers and other highly paid professionals from the same sort of international competition faced by autoworkers and textile workers.

Republicans support keeping in place a tax code that is littered with tax breaks, the exploitation of which is the primary basis for the existence of the private equity industry. (See my colleague Eileen Appelbaum’s forthcoming book on this topic.) Republicans support a special exemption of the financial industry from the sort of taxes that apply to other industries. This implicitly means higher taxes on other sectors of the economy and allows people to get ridiculously rich in finance. And they support a budget policy that keep millions of people out of work and puts downward pressure on the wages of most workers.

In short, it is absurd to say that the Republicans want the government to do little; they want the government to intervene in huge ways to redistribute income upward. Of course they don’t openly say this, they would much rather pretend that all the policies they support that lead to an upward redistribution of income are just the natural workings of the market. In this way, the NYT has done them a great service in uncritically projecting the Republicans’ romanticized image to readers as reflecting reality. However this completely distorts the relevant issues at play.

The real question is whether either party is prepared to attack the policies that have shifted such a vast amount of income upward over the last three decades. For practical purposes, if these policies are not changed, the agenda on mobility is just silly happy talk and everyone knows it. If the current policies promoting inequality are left in place there is nothing that Washington can do that can affect in more than a trivial way the life prospects of those in the bottom half and especially the bottom quintile of the income distribution.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT was almost as bad as the Washington Post in its reporting on the farm bill. The NYT gets a few points for explaining how many people would be hit by the cuts in food stamps and what the cuts translated to in dollars per month.

But the main numbers still appeared as just really big numbers. No one knows what $1 trillion in spending means over the next decade and the article offers no context to provide meaning. So, this one will get a good humma, humma, humma, down at the budget reporters’ frat house, but provides almost no information to readers.

The NYT had committed itself to placing these numbers in context more than three months ago. What is going on? It really is not that hard.

The NYT was almost as bad as the Washington Post in its reporting on the farm bill. The NYT gets a few points for explaining how many people would be hit by the cuts in food stamps and what the cuts translated to in dollars per month.

But the main numbers still appeared as just really big numbers. No one knows what $1 trillion in spending means over the next decade and the article offers no context to provide meaning. So, this one will get a good humma, humma, humma, down at the budget reporters’ frat house, but provides almost no information to readers.

The NYT had committed itself to placing these numbers in context more than three months ago. What is going on? It really is not that hard.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post gave us some good frat boy budget reporting in a front page story on the farm bill this morning. Frat boy budget reporting is when you write a piece that provides no information to the vast majority of readers but lets you go down to the budget reporters’ frat house and give each other the budget reporters’ secret handshake. In this case, the piece told us that the farm bill will cost $956.4 billion over the next decade, it will reduce spending on SNAP by $8 billion and save $16 billion in total.

Yes, this is really helpful. At least 0.1 percent of Washington Post readers have any clue what these numbers mean for the budget over the next decade. It is possible and easy to express these numbers in ways that would be meaningful.

CEPR’s extraordinary Responsible Budget Reporting Calculator would allow any budget reporters to determine in seconds that the total bill is 2.05 percent of projected spending, which immediately would give the vast majority of Post readers a clear idea of the farm bill’s importance to the budget. They could also quickly recognize that the cuts to the SNAP bill are 0.017 percent of projected spending and the total savings on the bill are 0.034 percent of projected spending.

It’s really not hard to do budget reporting in a way that provides information to its audience. However the Post simply chooses not to.

The Washington Post gave us some good frat boy budget reporting in a front page story on the farm bill this morning. Frat boy budget reporting is when you write a piece that provides no information to the vast majority of readers but lets you go down to the budget reporters’ frat house and give each other the budget reporters’ secret handshake. In this case, the piece told us that the farm bill will cost $956.4 billion over the next decade, it will reduce spending on SNAP by $8 billion and save $16 billion in total.

Yes, this is really helpful. At least 0.1 percent of Washington Post readers have any clue what these numbers mean for the budget over the next decade. It is possible and easy to express these numbers in ways that would be meaningful.

CEPR’s extraordinary Responsible Budget Reporting Calculator would allow any budget reporters to determine in seconds that the total bill is 2.05 percent of projected spending, which immediately would give the vast majority of Post readers a clear idea of the farm bill’s importance to the budget. They could also quickly recognize that the cuts to the SNAP bill are 0.017 percent of projected spending and the total savings on the bill are 0.034 percent of projected spending.

It’s really not hard to do budget reporting in a way that provides information to its audience. However the Post simply chooses not to.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Apparently a lot of media folks have made such a habit of repeating Republican talking points that they can’t see what is right in front of their eyes. The Republicans are touting the fact that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expects the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to reduce the number of people working.

Guess what? This was one of the motivations for the ACA. It is a feature, not a bug. There are a lot of people who would prefer not to work and would not work if they had some other way to get health care insurance. Imagine a 62 year-old with diabetes and other health conditions. No insurer will touch this person. If they can get insurance at all they are looking at bill that will certainly run well over $10k a year. If this person has a job that provides insurance they will keep it until they qualify for Medicare no matter how much of a struggle it is to go to work each day.

Now with the ACA this person will be able to buy insurance at the same price as anyone else in the age 55-64 age group. If they can get by on their Social Security and prior savings then they may well decide to retire early. They may also qualify for a subsidy in the exchanges. Is this an awful story? You be the judge.

The other likely scenario is the case of a mother with a newly born child. She may want to spend some time at home with her kid, but may have no other way to pay for her health insurance if she leaves her job. The ACA will give her an opportunity to get lower cost insurance (possibly with a subsidy). Again, is a mother taking some off to be with a new born kid a horror story?

Finally, we should be very clear about what CBO said on wages since there really is no ambiguity here. It said:

“According to CBO’s more detailed analysis, the 1 percent reduction in aggregate compensation that will occur as a result of the ACA corresponds to a reduction of about 1.5 percent to 2.0 percent in hours worked. (p 127)”

If hours fall by 1.5 to 2.0 percent, but compensation falls by 1.0 percent, then compensation per hour rises by 0.5-1.0 percent due to the ACA. If this is bad news for workers then someone must have been enjoying the new found freedoms in Colorado or Washington State too much.

Apparently a lot of media folks have made such a habit of repeating Republican talking points that they can’t see what is right in front of their eyes. The Republicans are touting the fact that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expects the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to reduce the number of people working.

Guess what? This was one of the motivations for the ACA. It is a feature, not a bug. There are a lot of people who would prefer not to work and would not work if they had some other way to get health care insurance. Imagine a 62 year-old with diabetes and other health conditions. No insurer will touch this person. If they can get insurance at all they are looking at bill that will certainly run well over $10k a year. If this person has a job that provides insurance they will keep it until they qualify for Medicare no matter how much of a struggle it is to go to work each day.

Now with the ACA this person will be able to buy insurance at the same price as anyone else in the age 55-64 age group. If they can get by on their Social Security and prior savings then they may well decide to retire early. They may also qualify for a subsidy in the exchanges. Is this an awful story? You be the judge.

The other likely scenario is the case of a mother with a newly born child. She may want to spend some time at home with her kid, but may have no other way to pay for her health insurance if she leaves her job. The ACA will give her an opportunity to get lower cost insurance (possibly with a subsidy). Again, is a mother taking some off to be with a new born kid a horror story?

Finally, we should be very clear about what CBO said on wages since there really is no ambiguity here. It said:

“According to CBO’s more detailed analysis, the 1 percent reduction in aggregate compensation that will occur as a result of the ACA corresponds to a reduction of about 1.5 percent to 2.0 percent in hours worked. (p 127)”

If hours fall by 1.5 to 2.0 percent, but compensation falls by 1.0 percent, then compensation per hour rises by 0.5-1.0 percent due to the ACA. If this is bad news for workers then someone must have been enjoying the new found freedoms in Colorado or Washington State too much.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, not much of a surprise here. (I had to check the date to be sure I wasn’t reading an old column.) Anyhow, let’s start with the punch line:

“Economic inequality is usually a consequence of our problems and not a cause. For starters, the poor are not poor because the rich are rich.

“The two conditions are generally unrelated. Mostly, the rich got rich by running profitable small businesses (car dealerships, builders), creating big enterprises (Google, Microsoft), being at the top of lucrative occupations (bankers, lawyers, doctors, actors, athletes), managing major companies or inheriting fortunes. By contrast, the very poor often face circumstances that make their lives desperate.”

Really? So the fact that doctors and lawyers secure themselves protection from competition and thereby drive up the cost of medical care and other products (yes, we do pay for corporate lawyers in the price of goods and services) doesn’t affect the income of the poor? Not where I learned arithmetic.

How about the fact that the rich use their control over politicians to get them to run high unemployment policies by reducing the deficit and demand in the economy. This costs low and middle income workers both jobs and wages (see Jared Bernstein and my book on the topic.)

Oh yeah, and what about the fact that the Wall Street boys can get themselves too big to fail subsidies from the government ($83 billion a year according to Bloomberg, a bit more than the SNAP budget)? And of course they also get exemptions from the sales taxes that other industries have to pay. Where does this money come from if not the rest of us?

But hey, Robert Samuelson tells us their wealth has nothing to do with other people suffering. Who are you going to listen to, common sense, logic, and arithmetic or Robert Samuelson?

Then we get Samuelson telling us:

“Finally, widening economic inequality is sometimes mistakenly blamed for causing the Great Recession and the weak recovery. The argument, as outlined by two economists at Washington University in St. Louis, goes like this: In the 1980s, income growth for the bottom 95 percent of Americans slowed. People compensated by borrowing more. All the extra debt led to a consumption boom that was unsustainable. The housing bubble and crash followed. Now, weak income growth of the bottom 95 percent ‘helps explain the slow recovery.’

Actually, the logic goes like this, as told by those of us who knew enough about the economy to see this crash coming. The economy suffers from weak demand because of so much money being redistributed upward to rich people who spend a smaller share of their income than middle and low income households. This problem was aggravated enormously by the explosion of the trade deficit that followed the run-up in the dollar due to botched East Asian financial crisis in 1997.

In the presence of weak demand the Fed allows interest rates to fall more than would otherwise be the case. In the absence of investment demand, these low interest rates create an environment that is very conducive to bubbles, hence we got the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade. In the absence of another bubble to boost the economy we are continuing to see slow growth and high unemployment.

That one is probably too simple for Robert Samuelson to understand, but for most other people it provides a pretty direct link between inequality and the economic and social disaster of the Great Recession.

So the story is pretty simple. The system has been rigged to redistribute income upward. The rich have used their control of the political process to ensure that it stays that way and their control of news outlets like the Washington Post to try to distort reality.

Yes, not much of a surprise here. (I had to check the date to be sure I wasn’t reading an old column.) Anyhow, let’s start with the punch line:

“Economic inequality is usually a consequence of our problems and not a cause. For starters, the poor are not poor because the rich are rich.

“The two conditions are generally unrelated. Mostly, the rich got rich by running profitable small businesses (car dealerships, builders), creating big enterprises (Google, Microsoft), being at the top of lucrative occupations (bankers, lawyers, doctors, actors, athletes), managing major companies or inheriting fortunes. By contrast, the very poor often face circumstances that make their lives desperate.”

Really? So the fact that doctors and lawyers secure themselves protection from competition and thereby drive up the cost of medical care and other products (yes, we do pay for corporate lawyers in the price of goods and services) doesn’t affect the income of the poor? Not where I learned arithmetic.

How about the fact that the rich use their control over politicians to get them to run high unemployment policies by reducing the deficit and demand in the economy. This costs low and middle income workers both jobs and wages (see Jared Bernstein and my book on the topic.)

Oh yeah, and what about the fact that the Wall Street boys can get themselves too big to fail subsidies from the government ($83 billion a year according to Bloomberg, a bit more than the SNAP budget)? And of course they also get exemptions from the sales taxes that other industries have to pay. Where does this money come from if not the rest of us?

But hey, Robert Samuelson tells us their wealth has nothing to do with other people suffering. Who are you going to listen to, common sense, logic, and arithmetic or Robert Samuelson?

Then we get Samuelson telling us:

“Finally, widening economic inequality is sometimes mistakenly blamed for causing the Great Recession and the weak recovery. The argument, as outlined by two economists at Washington University in St. Louis, goes like this: In the 1980s, income growth for the bottom 95 percent of Americans slowed. People compensated by borrowing more. All the extra debt led to a consumption boom that was unsustainable. The housing bubble and crash followed. Now, weak income growth of the bottom 95 percent ‘helps explain the slow recovery.’

Actually, the logic goes like this, as told by those of us who knew enough about the economy to see this crash coming. The economy suffers from weak demand because of so much money being redistributed upward to rich people who spend a smaller share of their income than middle and low income households. This problem was aggravated enormously by the explosion of the trade deficit that followed the run-up in the dollar due to botched East Asian financial crisis in 1997.

In the presence of weak demand the Fed allows interest rates to fall more than would otherwise be the case. In the absence of investment demand, these low interest rates create an environment that is very conducive to bubbles, hence we got the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade. In the absence of another bubble to boost the economy we are continuing to see slow growth and high unemployment.

That one is probably too simple for Robert Samuelson to understand, but for most other people it provides a pretty direct link between inequality and the economic and social disaster of the Great Recession.

So the story is pretty simple. The system has been rigged to redistribute income upward. The rich have used their control of the political process to ensure that it stays that way and their control of news outlets like the Washington Post to try to distort reality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión