The NYT had an interesting piece on a dispute over continuing a clinical trial of a heart device that has been tied to a number of incidents of blood clots. While the device had originally been used in patients who likely risked death without it, the trial is designed to examine its effectiveness in patients with less severe heart disease. The incidents of blood clots raise the possibility that the risk exceeds the potential benefit.

At one point the article noted that the doctors working with the device maker continue to defend the safety of the device and intend to continue the clinical study. It then quotes a cardiologist at Duke, one of the authors of a study showing the higher incidence of blood clots, who notes that these doctors had spent years setting up the trial:

“They are more apt to look at the data that suggests there is less of a problem, …”

It would have been worth noting that in addition to the time they spent setting up the study, they also likely stand to make a substantial amount of money if the device is approved for use in a larger group of patients. This is a function of patent support for the research and development of medical devices.

It is likely that researchers will want to defend their research in any case, since they will be reluctant to accept that years might have been wasted. However the incentive to pursue a line of research even if new evidence suggests it is counterproductive will be much greater if there is potentially a large monetary reward. At least, this is what economic theory predicts.

The NYT had an interesting piece on a dispute over continuing a clinical trial of a heart device that has been tied to a number of incidents of blood clots. While the device had originally been used in patients who likely risked death without it, the trial is designed to examine its effectiveness in patients with less severe heart disease. The incidents of blood clots raise the possibility that the risk exceeds the potential benefit.

At one point the article noted that the doctors working with the device maker continue to defend the safety of the device and intend to continue the clinical study. It then quotes a cardiologist at Duke, one of the authors of a study showing the higher incidence of blood clots, who notes that these doctors had spent years setting up the trial:

“They are more apt to look at the data that suggests there is less of a problem, …”

It would have been worth noting that in addition to the time they spent setting up the study, they also likely stand to make a substantial amount of money if the device is approved for use in a larger group of patients. This is a function of patent support for the research and development of medical devices.

It is likely that researchers will want to defend their research in any case, since they will be reluctant to accept that years might have been wasted. However the incentive to pursue a line of research even if new evidence suggests it is counterproductive will be much greater if there is potentially a large monetary reward. At least, this is what economic theory predicts.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had a useful piece on the Treasury Department’s adoption of a stronger than expected version of the Volcker Rule, which is likely to seriously limit the extent of proprietary trading at the major banks. At one point the piece tells readers;

“In anticipation of the Volcker rule, many large banks, including JPMorgan, have shuttered or spun off their proprietary trading desks, as well as their private-

equity arms and hedge funds. That could blunt the full force of the rule, analysts say.”

It’s not clear what this could mean, since the point of the Volcker Rule was to keep banks from engaging in proprietary trading. If they have spun off their trading desks then its purpose will have been accomplished. The goal is not to prevent trading, but to prevent banks from effectively speculating with government guaranteed deposits.

The Washington Post had a useful piece on the Treasury Department’s adoption of a stronger than expected version of the Volcker Rule, which is likely to seriously limit the extent of proprietary trading at the major banks. At one point the piece tells readers;

“In anticipation of the Volcker rule, many large banks, including JPMorgan, have shuttered or spun off their proprietary trading desks, as well as their private-

equity arms and hedge funds. That could blunt the full force of the rule, analysts say.”

It’s not clear what this could mean, since the point of the Volcker Rule was to keep banks from engaging in proprietary trading. If they have spun off their trading desks then its purpose will have been accomplished. The goal is not to prevent trading, but to prevent banks from effectively speculating with government guaranteed deposits.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ross Douthat raises an interesting issue in his column on Obamacare. Douthat suggests that Obamacare may not succeed elsewhere in the same way as it did in Massachusetts because people don’t feel as warmly inclined toward the government in other states.

There are several pieces of Douthat’s story that aren’t quite right. First, this is private insurance, not government insurance. It’s not clear how people think they would be making a strike against the government by not buying private insurance, but we can skip that one.

Douthat also follows the pack in buying the young invincible story. The key to the success of Obamacare is getting healthy people to sign up. It doesn’t matter what age they are. In fact, the program gets three times as much money out of every healthy senior as it does from a healthy twenty five-year-old. In fact, the gap is likely to be even larger since young people are more likely to get a subsidy since their income is on average lower.

But it is at least possible that we will see the adverse selection story that Douthat raises, although the outcome will not be quite what he envisions. Under Obamacare each state is effectively its own pool.

Clearly there are other states where people are likely to act like the people in Massachusetts and sign up for health insurance. But there could also be states, let’s call them Texas, where many healthy people may decide that as a matter of principle they will not sign up for Obamacare.

This would give us the classic death spiral. If fewer healthy people sign up for insurance then the cost of the insurance will rise. This will lead more relatively healthy people to opt not to sign up. That would further raise the cost of insurance, leading more people to drop insurance. The end game is that Obamacare in these states could end up as a shell. The costs could be so high that almost no one takes advantage of the exchanges and instead just pays the penalty.

This would create a striking gap between the states where Obamacare worked and the exchanges were running well and Texas, where a large share of the population would not have insurance. We have already seen a split along these lines with the refusal of Texas and other states controlled by Republicans to expand Medicaid with federal funds, as provided for under the ACA. However the collapse of the exchanges would affect a much larger and more politically influential segment of the population. This would directly affect the security of middle class workers.

It’s not clear that the people of Texas would be happy with the outcome of their individual decisions if the collapse of the exchanges really was the outcome. Tens of millions of workers in the non-Texas states would enjoy security in their health insurance. If they lost their jobs or had some other adverse set of events they would still be able to buy a reasonably priced insurance plan. That would not be the case in Texas.

That outcome would be unfortunate for the people of Texas, but it might lead to an interesting political dynamic.

Ross Douthat raises an interesting issue in his column on Obamacare. Douthat suggests that Obamacare may not succeed elsewhere in the same way as it did in Massachusetts because people don’t feel as warmly inclined toward the government in other states.

There are several pieces of Douthat’s story that aren’t quite right. First, this is private insurance, not government insurance. It’s not clear how people think they would be making a strike against the government by not buying private insurance, but we can skip that one.

Douthat also follows the pack in buying the young invincible story. The key to the success of Obamacare is getting healthy people to sign up. It doesn’t matter what age they are. In fact, the program gets three times as much money out of every healthy senior as it does from a healthy twenty five-year-old. In fact, the gap is likely to be even larger since young people are more likely to get a subsidy since their income is on average lower.

But it is at least possible that we will see the adverse selection story that Douthat raises, although the outcome will not be quite what he envisions. Under Obamacare each state is effectively its own pool.

Clearly there are other states where people are likely to act like the people in Massachusetts and sign up for health insurance. But there could also be states, let’s call them Texas, where many healthy people may decide that as a matter of principle they will not sign up for Obamacare.

This would give us the classic death spiral. If fewer healthy people sign up for insurance then the cost of the insurance will rise. This will lead more relatively healthy people to opt not to sign up. That would further raise the cost of insurance, leading more people to drop insurance. The end game is that Obamacare in these states could end up as a shell. The costs could be so high that almost no one takes advantage of the exchanges and instead just pays the penalty.

This would create a striking gap between the states where Obamacare worked and the exchanges were running well and Texas, where a large share of the population would not have insurance. We have already seen a split along these lines with the refusal of Texas and other states controlled by Republicans to expand Medicaid with federal funds, as provided for under the ACA. However the collapse of the exchanges would affect a much larger and more politically influential segment of the population. This would directly affect the security of middle class workers.

It’s not clear that the people of Texas would be happy with the outcome of their individual decisions if the collapse of the exchanges really was the outcome. Tens of millions of workers in the non-Texas states would enjoy security in their health insurance. If they lost their jobs or had some other adverse set of events they would still be able to buy a reasonably priced insurance plan. That would not be the case in Texas.

That outcome would be unfortunate for the people of Texas, but it might lead to an interesting political dynamic.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

NPR used the phrase “massive” stimulus in describing the Fed’s quantitative easing policy in its top of the hour news segment on Morning Edition. It is arguable whether the stimulus is “massive.” There is certainly a plausible argument that the stimulus is too small since unemployment remains high and inflation is running below the Fed’s 2.0 percent target. NPR could have saved time and increased accuracy by just referring to the program as “stimulus.”

NPR used the phrase “massive” stimulus in describing the Fed’s quantitative easing policy in its top of the hour news segment on Morning Edition. It is arguable whether the stimulus is “massive.” There is certainly a plausible argument that the stimulus is too small since unemployment remains high and inflation is running below the Fed’s 2.0 percent target. NPR could have saved time and increased accuracy by just referring to the program as “stimulus.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the country is foregoing close to $1 trillion a year in output because the budgets produced by Congress do not provide enough demand to bring the economy to full employment. These losses are disproportionately incurred by minorities, the young, and the poor, since these are the groups most likely to be unemployed or working fewer hours at lower pay because of Congress’s failure.

However, the failure of Congress to produce a budget that would spur growth and reduce unemployment never once got mentioned in the Post’s lead front page article. The only outside experts to give comments in the piece were Robert Bixby, the executive director of the Peter Peterson financed Concord Coalition and Gene Steuerle, who formerly was vice-president of the Peter Peterson Foundation.

While the article never discusses the impact of the budget on the economy, it repeatedly complains that the tentative budget agreement reached by the congressional negotiators doesn’t reduce the debt by as much as the Post would like. Most newspapers would keep such editorializing to the opinion pages.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the country is foregoing close to $1 trillion a year in output because the budgets produced by Congress do not provide enough demand to bring the economy to full employment. These losses are disproportionately incurred by minorities, the young, and the poor, since these are the groups most likely to be unemployed or working fewer hours at lower pay because of Congress’s failure.

However, the failure of Congress to produce a budget that would spur growth and reduce unemployment never once got mentioned in the Post’s lead front page article. The only outside experts to give comments in the piece were Robert Bixby, the executive director of the Peter Peterson financed Concord Coalition and Gene Steuerle, who formerly was vice-president of the Peter Peterson Foundation.

While the article never discusses the impact of the budget on the economy, it repeatedly complains that the tentative budget agreement reached by the congressional negotiators doesn’t reduce the debt by as much as the Post would like. Most newspapers would keep such editorializing to the opinion pages.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

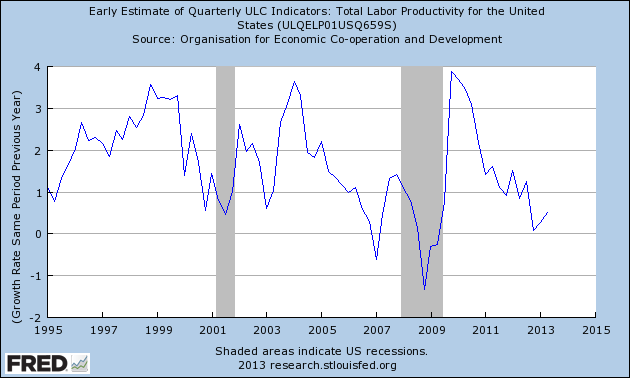

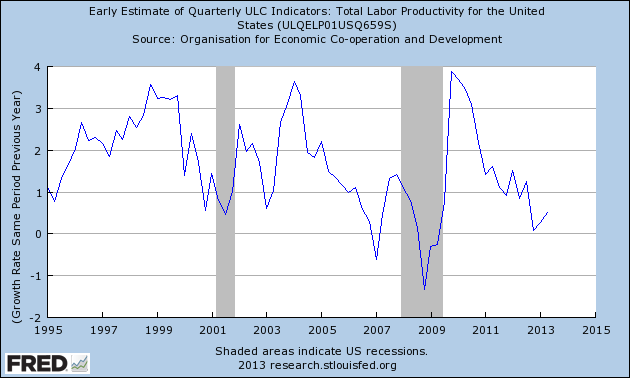

No one expects Thomas Friedman to base his columns on evidence, but he strayed even farther than usual today. The piece is a complaint that the United States is not prepared to deal with “a huge technological transformation in the middle of a recession.” The data won’t support that one.

The usual measure of technological progress is productivity growth. That has been lagging in this upturn, averaging close to 1.0 percent for the last three years.

We know that Thomas Friedman has lots of stories from his cab drivers and other people that he talks to, but most of us might opt to rely on the data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics instead.

Friedman is also a bit behind the times in telling us about the loss of middle skilled jobs. That might have been a story for the 1980s, but the data have not supported Friedman’s story for at least a decade.

Friedman also feels the need to lecture liberals, saying they:

“need to think more seriously about how we incentivize and unleash risk-takers to start new companies that create growth, wealth and good jobs. To have more employees, we need more employers.”

Of course many people on the left have given lots of thought to exactly this issue. Putting a tax on financial speculation and breaking up the big banks would reduce the amount of resources diverted to unproductive activity in the financial sector. Developing a more efficient alternative to patent monopolies to support pharmaceutical research would free up hundreds of billions of dollars a year. And of course the main agenda item at the moment simply has to be to stimulate the economy to end the $1 trillion needless waste of potential GDP.

The problem is not a lack of thinking on the part of the left. The problem is that Friedman is too lazy to pay attention to what people on the left are saying.

No one expects Thomas Friedman to base his columns on evidence, but he strayed even farther than usual today. The piece is a complaint that the United States is not prepared to deal with “a huge technological transformation in the middle of a recession.” The data won’t support that one.

The usual measure of technological progress is productivity growth. That has been lagging in this upturn, averaging close to 1.0 percent for the last three years.

We know that Thomas Friedman has lots of stories from his cab drivers and other people that he talks to, but most of us might opt to rely on the data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics instead.

Friedman is also a bit behind the times in telling us about the loss of middle skilled jobs. That might have been a story for the 1980s, but the data have not supported Friedman’s story for at least a decade.

Friedman also feels the need to lecture liberals, saying they:

“need to think more seriously about how we incentivize and unleash risk-takers to start new companies that create growth, wealth and good jobs. To have more employees, we need more employers.”

Of course many people on the left have given lots of thought to exactly this issue. Putting a tax on financial speculation and breaking up the big banks would reduce the amount of resources diverted to unproductive activity in the financial sector. Developing a more efficient alternative to patent monopolies to support pharmaceutical research would free up hundreds of billions of dollars a year. And of course the main agenda item at the moment simply has to be to stimulate the economy to end the $1 trillion needless waste of potential GDP.

The problem is not a lack of thinking on the part of the left. The problem is that Friedman is too lazy to pay attention to what people on the left are saying.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had a major article on how the drug company Genentech has managed to create a substantial market for its drug Lucentis, at a price of $2,000 per injection, even though it manufactures another drug Aventis, which is just as effective and sells for $50 an injection. Both are used to prevent blindness. A number of studies have shown them to be equally effective. The article explains how Genentech has been able to maintain a market for a drug that costs 40 times as much as its equivalent competitor, most importantly by not seeking approval from the Food and Drug Administration for the use of Aventis as a treatment to prevent blindness.

While the article is fascinating, it would have been helpful to include the views of an economist who could have pointed out that this is exactly the sort of corruption that economic theory predicts would result from the granting of patent monopolies by the government. Government granted monopolies would lead to distortions in any case, but they are likely to be especially large with a product like prescription drugs, where there are enormous asymmetries of information. The drug companies know much more about their drugs than patients or even their doctors.

It would be reasonable to discuss more efficient mechanisms for financing prescription drug research, such as direct public funding (we already spend $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health). Unfortunately the drug companies so completely dominate the political process news outlets like the Post never even mention alternatives to patent monopolies. However, they do occasionally document some of the predictable corruption, as is the case here.

The Washington Post had a major article on how the drug company Genentech has managed to create a substantial market for its drug Lucentis, at a price of $2,000 per injection, even though it manufactures another drug Aventis, which is just as effective and sells for $50 an injection. Both are used to prevent blindness. A number of studies have shown them to be equally effective. The article explains how Genentech has been able to maintain a market for a drug that costs 40 times as much as its equivalent competitor, most importantly by not seeking approval from the Food and Drug Administration for the use of Aventis as a treatment to prevent blindness.

While the article is fascinating, it would have been helpful to include the views of an economist who could have pointed out that this is exactly the sort of corruption that economic theory predicts would result from the granting of patent monopolies by the government. Government granted monopolies would lead to distortions in any case, but they are likely to be especially large with a product like prescription drugs, where there are enormous asymmetries of information. The drug companies know much more about their drugs than patients or even their doctors.

It would be reasonable to discuss more efficient mechanisms for financing prescription drug research, such as direct public funding (we already spend $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health). Unfortunately the drug companies so completely dominate the political process news outlets like the Post never even mention alternatives to patent monopolies. However, they do occasionally document some of the predictable corruption, as is the case here.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ezra Klein highlights the most important feature of Obamacare. People who have insurance now will be assured that they can still buy it if they lose it for some reason. This will make a huge difference to the bulk of the population who do already have insurance. They can now change jobs or even quit and still be assured of being able to get insurance at a reasonable price.

Ezra Klein highlights the most important feature of Obamacare. People who have insurance now will be assured that they can still buy it if they lose it for some reason. This will make a huge difference to the bulk of the population who do already have insurance. They can now change jobs or even quit and still be assured of being able to get insurance at a reasonable price.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Neil Irwin seems to miss the major issues on too big to fail in his discussion of Treasury Secretary Jack Lew’s remarks proclaiming too big to fail (TBTF) to be sort of over. The most obvious issue is simply whether the markets believe TBTF is over.

This is a question of whether they think Jack Lew or his successors will simply wave good bye if J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs, or one of the other megabanks goes under. If they don’t believe that the government will just let one of these banks sink then they will still be willing to lend money to them at a below market rate since they are counting on the government to back up their loans.

This below market interest rate amounts to a massive subsidy to the top executives and shareholders of these banks. Bloomberg news estimated the size of this subsidy at $83 billion a year, more than the cost of the food stamp program. Insofar as Lew’s efforts to create doubts about a government rescue are successful, the size of this subsidy would shrink toward zero. However as long as the markets do not take him seriously (my bet is they don’t), the big banks will still be getting a massive subsidy.

This is one of the reasons why President Obama’s recent comments on inequality were seriously misplaced. He said the government cannot stand on the sidelines as the distribution of income becomes much more unequal. Of course government is not standing on the sidelines; it is actively working to increase inequality through measures like the TBTF subsidy.

The other point that Irwin gets wrong is implying that the economic crisis in some way hinged on getting the TBTF issue right. The economy’s current weakness is attributable to a lack of a source of demand to replace the demand generated by the housing bubble. Investment and consumption are both at normal levels relative to the size of the economy; there is no evidence that the residue of the financial crisis is holding them back.

The issue going forward will be whether we have people at the Fed and other regulatory agencies who take bubbles seriously. We clearly did not in the past and since no one faced any career consequences as a result of this gargantuan failure, there is not much reason to believe that lessons have been learned.

Neil Irwin seems to miss the major issues on too big to fail in his discussion of Treasury Secretary Jack Lew’s remarks proclaiming too big to fail (TBTF) to be sort of over. The most obvious issue is simply whether the markets believe TBTF is over.

This is a question of whether they think Jack Lew or his successors will simply wave good bye if J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs, or one of the other megabanks goes under. If they don’t believe that the government will just let one of these banks sink then they will still be willing to lend money to them at a below market rate since they are counting on the government to back up their loans.

This below market interest rate amounts to a massive subsidy to the top executives and shareholders of these banks. Bloomberg news estimated the size of this subsidy at $83 billion a year, more than the cost of the food stamp program. Insofar as Lew’s efforts to create doubts about a government rescue are successful, the size of this subsidy would shrink toward zero. However as long as the markets do not take him seriously (my bet is they don’t), the big banks will still be getting a massive subsidy.

This is one of the reasons why President Obama’s recent comments on inequality were seriously misplaced. He said the government cannot stand on the sidelines as the distribution of income becomes much more unequal. Of course government is not standing on the sidelines; it is actively working to increase inequality through measures like the TBTF subsidy.

The other point that Irwin gets wrong is implying that the economic crisis in some way hinged on getting the TBTF issue right. The economy’s current weakness is attributable to a lack of a source of demand to replace the demand generated by the housing bubble. Investment and consumption are both at normal levels relative to the size of the economy; there is no evidence that the residue of the financial crisis is holding them back.

The issue going forward will be whether we have people at the Fed and other regulatory agencies who take bubbles seriously. We clearly did not in the past and since no one faced any career consequences as a result of this gargantuan failure, there is not much reason to believe that lessons have been learned.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión