That’s what readers of this AP interview with Greenspan must be asking. Greenspan was asked about the crisis caused by the collapse of the housing bubble (inaccurately referred to in the interview as the “financial crisis). He responded by saying:

“A: The problem is that we didn’t know about it [the growth of the subprime market]. It was a big surprise to me how big the subprime market had gotten by 2005. I was told very little of the problems were under Fed supervision. But still, if we had seen something big, we would have made a big fuss about it. But we didn’t. We were wrong. Could we have caught it? I don’t know.”

The correct response from the interviewer should have been an astonished, “you are claiming that you did not know of the enormous growth of the subprime market by 2005? It was widely talked about in the business press and documented in a number of different data series. How could the Fed chair possibly have missed the explosion of exotic mortgages?”

It is preposterous that Greenspan would make such a claim. Everyone who was paying any attention to the housing market was joking about the proliferation of “NINJA” loans, which meant no income, no jobs, no assets. The Fed chair really didn’t have a clue of this?

His professed ignorance on this topic is astounding. If he really missed the flood of bad mortgages that was propelling the unprecedented rise in house prices then he was not doing his job. He should repay the taxpayers his salary for these years, he obviously did not work for it.

That’s what readers of this AP interview with Greenspan must be asking. Greenspan was asked about the crisis caused by the collapse of the housing bubble (inaccurately referred to in the interview as the “financial crisis). He responded by saying:

“A: The problem is that we didn’t know about it [the growth of the subprime market]. It was a big surprise to me how big the subprime market had gotten by 2005. I was told very little of the problems were under Fed supervision. But still, if we had seen something big, we would have made a big fuss about it. But we didn’t. We were wrong. Could we have caught it? I don’t know.”

The correct response from the interviewer should have been an astonished, “you are claiming that you did not know of the enormous growth of the subprime market by 2005? It was widely talked about in the business press and documented in a number of different data series. How could the Fed chair possibly have missed the explosion of exotic mortgages?”

It is preposterous that Greenspan would make such a claim. Everyone who was paying any attention to the housing market was joking about the proliferation of “NINJA” loans, which meant no income, no jobs, no assets. The Fed chair really didn’t have a clue of this?

His professed ignorance on this topic is astounding. If he really missed the flood of bad mortgages that was propelling the unprecedented rise in house prices then he was not doing his job. He should repay the taxpayers his salary for these years, he obviously did not work for it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Simon Nixon appears nearly ecstatic over the what he terms the “strong recovery” in the United Kingdom. The problem is his notion of strong recovery doesn’t fit the usual definition of the term.

According to the new upgraded growth projections from the I.M.F., which he highlights, the U.K. is projected to see 1.6 percent year over year growth in 2013. That would leave per capita income in 2013 about 6.0 percent below its 2007 level. The new upgraded projections show per capita income in the UK getting back to its 2007 level in 2018. Eleven years of zero rise in per capita GDP is certainly a new definition of success.

Even worse, this recovery is almost certainly not sustainable since it is being driven by a re-invigoration of the U.K.’s housing bubble. House prices in the U.K. are on average about 60 percent higher than in the U.S.. (In the mid-1990s they were about 10 percent less.) They are again rising rapidly driven in part by a policy of the Cameron government to promote homeownership that seems deliberately designed to re-inflate its housing bubble in advance of the election. Of course after bubble bursts we can expect another grand chorus of “who could have known?“

Simon Nixon appears nearly ecstatic over the what he terms the “strong recovery” in the United Kingdom. The problem is his notion of strong recovery doesn’t fit the usual definition of the term.

According to the new upgraded growth projections from the I.M.F., which he highlights, the U.K. is projected to see 1.6 percent year over year growth in 2013. That would leave per capita income in 2013 about 6.0 percent below its 2007 level. The new upgraded projections show per capita income in the UK getting back to its 2007 level in 2018. Eleven years of zero rise in per capita GDP is certainly a new definition of success.

Even worse, this recovery is almost certainly not sustainable since it is being driven by a re-invigoration of the U.K.’s housing bubble. House prices in the U.K. are on average about 60 percent higher than in the U.S.. (In the mid-1990s they were about 10 percent less.) They are again rising rapidly driven in part by a policy of the Cameron government to promote homeownership that seems deliberately designed to re-inflate its housing bubble in advance of the election. Of course after bubble bursts we can expect another grand chorus of “who could have known?“

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steven Pearlstein reviewed Alan Greenspan’s new book in the Washington Post today. He is far too generous to the former Maestro.

Pearlstein tells readers:

“Like Fred Astaire on the dance floor, Greenspan glides through the list without the slightest sign he might have had something to do with those developments. What he does remember is that during his watch, the markets and the economy quickly recovered after asset bubbles burst — in 1987 (junk bonds) and again in 2001 (dot-com). Based on those happy outcomes, Greenspan confidently reprises his now widely discredited view that, in the long run, the economy is better off if the government restricts itself to cleaning up after bubbles rather than trying to prevent them from growing too large.”

It is more than a bit silly to compare the bursting of the stock bubble (not dot-com, the market in general was hugely over-valued) and the housing bubble to the 1987 crash. The market had gained a great deal of value in the year of 1987. After the crash in October it quickly began to make back lost ground and by the end of the year the market was at virtually the same level as the beginning of the year. No one thinks that the economy is affected in any significant way by short-terms movements in the market, so there was really nothing to clean up in this story.

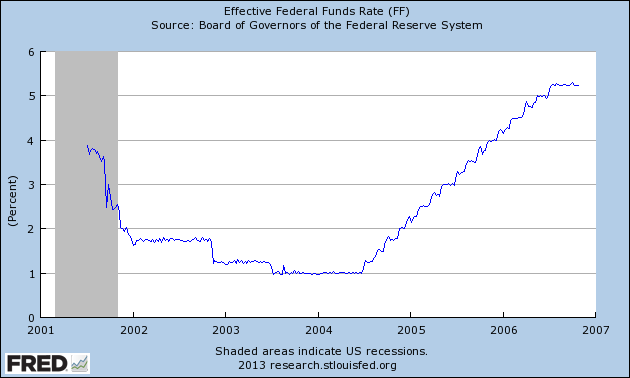

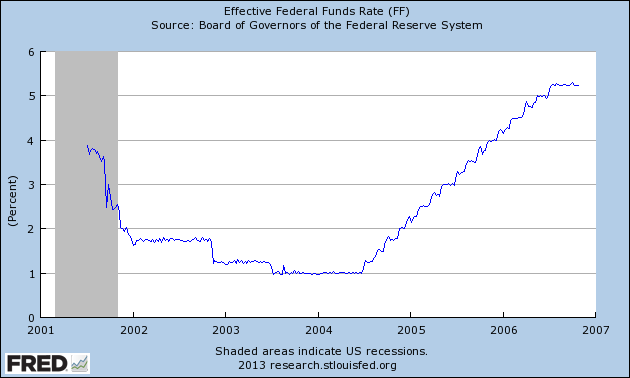

The picture was very different following the 2001 crash which resulted in the elimination of roughly $10 trillion in stock bubble wealth, an amount approximately to the economy’s GDP. The economy did not recovery quickly following this crash. While the recession was officially short and mild, ending in 2001, the economy did not begin to create jobs again until the fall of 2003, almost two years after the recession was over. It did not get back the jobs lost in the recession until January of 2005. At the time, this was the longest period without job growth since the Great Depression.

The Fed seemed to take notice of the weakness of the economy keeping the federal funds rate at just 1.0 percent until the summer of 2004. This can be seen as effectively the zero lower bound. No one thinks that there is any great stimulatory effect from dropping the rate from 1.0 percent to zero, which is why people routinely talked about the European Central Bank as being at its zero lower bound even when its overnight interest rate was 1.0 percent.

Of course even when the economy did finally bounce back it was on the back of the housing bubble, which was not a very stable course. In other words, if Greenspan thinks he can point to evidence that the economy recovers quickly from the collapse of asset bubbles it is only because he is very confused about basic economic facts.

Steven Pearlstein reviewed Alan Greenspan’s new book in the Washington Post today. He is far too generous to the former Maestro.

Pearlstein tells readers:

“Like Fred Astaire on the dance floor, Greenspan glides through the list without the slightest sign he might have had something to do with those developments. What he does remember is that during his watch, the markets and the economy quickly recovered after asset bubbles burst — in 1987 (junk bonds) and again in 2001 (dot-com). Based on those happy outcomes, Greenspan confidently reprises his now widely discredited view that, in the long run, the economy is better off if the government restricts itself to cleaning up after bubbles rather than trying to prevent them from growing too large.”

It is more than a bit silly to compare the bursting of the stock bubble (not dot-com, the market in general was hugely over-valued) and the housing bubble to the 1987 crash. The market had gained a great deal of value in the year of 1987. After the crash in October it quickly began to make back lost ground and by the end of the year the market was at virtually the same level as the beginning of the year. No one thinks that the economy is affected in any significant way by short-terms movements in the market, so there was really nothing to clean up in this story.

The picture was very different following the 2001 crash which resulted in the elimination of roughly $10 trillion in stock bubble wealth, an amount approximately to the economy’s GDP. The economy did not recovery quickly following this crash. While the recession was officially short and mild, ending in 2001, the economy did not begin to create jobs again until the fall of 2003, almost two years after the recession was over. It did not get back the jobs lost in the recession until January of 2005. At the time, this was the longest period without job growth since the Great Depression.

The Fed seemed to take notice of the weakness of the economy keeping the federal funds rate at just 1.0 percent until the summer of 2004. This can be seen as effectively the zero lower bound. No one thinks that there is any great stimulatory effect from dropping the rate from 1.0 percent to zero, which is why people routinely talked about the European Central Bank as being at its zero lower bound even when its overnight interest rate was 1.0 percent.

Of course even when the economy did finally bounce back it was on the back of the housing bubble, which was not a very stable course. In other words, if Greenspan thinks he can point to evidence that the economy recovers quickly from the collapse of asset bubbles it is only because he is very confused about basic economic facts.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

You’ve got to love those Washington Post folks. They continuously use both their news and editorial sections to push for cuts to Social Security, Medicare, and disability insurance, running roughshod over journalistic standards and data. But when it comes to the Wall Street boys, they just can’t help but to tear at our heart strings.

Last week the Post ran an editorial bemoaning the “political persecution” of J.P. Morgan. It complained that the government was pursuing a civil case against J.P. Morgan for misrepresenting mortgage backed securities it sold to investors during the housing bubble years:

“Yet roughly 70?percent of the securities at issue were concocted not by JPMorgan but by two institutions, Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual, that it acquired in 2008.”

There are two points worth making on this. First, if 70 percent of the securities came from Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual, then 30 percent came from J.P. Morgan. This means that it could have been involved in misrepresenting tens of billions of dollars in mortgage backed securities sold to investors. We have young men sitting in jail for stealing cars worth a few thousand dollars, but the Post thinks that Wall Street bankers should get a pass on fraudulently passing off tens of billions in bad mortgage backed securities.

The other point is that executives of large corporations like J.P. Morgan are supposed to understand that when they take over a company it can involve both upside and downside risks. On the upside, the company may have product lines or assets that the buyer did not fully appreciate at the time of the acquisition. On the downside, it may have liabilities such as the legal issues being raised in the Justice Department suit.

Believers in free markets would expect that a CEO like J.P. Morgan’s Jamie Dimon understood such risks at the time he chose to buy up Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual. However the Post apparently feels that he and his bank need a special hand from the government to change the terms of the deal after the fact and release J.P. Morgan from the billions of dollars of liabilities they inherited when they bought the banks. Their concern for the desperate plight of the Wall Street bankers is touching, but those of us who believe in free markets must insist on contracts being respected and laws being enforced.

It is worth noting that J.P. Morgan apparently disagreed with the Post and thought that the government had a pretty good case since it settled for $13 billion.

You’ve got to love those Washington Post folks. They continuously use both their news and editorial sections to push for cuts to Social Security, Medicare, and disability insurance, running roughshod over journalistic standards and data. But when it comes to the Wall Street boys, they just can’t help but to tear at our heart strings.

Last week the Post ran an editorial bemoaning the “political persecution” of J.P. Morgan. It complained that the government was pursuing a civil case against J.P. Morgan for misrepresenting mortgage backed securities it sold to investors during the housing bubble years:

“Yet roughly 70?percent of the securities at issue were concocted not by JPMorgan but by two institutions, Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual, that it acquired in 2008.”

There are two points worth making on this. First, if 70 percent of the securities came from Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual, then 30 percent came from J.P. Morgan. This means that it could have been involved in misrepresenting tens of billions of dollars in mortgage backed securities sold to investors. We have young men sitting in jail for stealing cars worth a few thousand dollars, but the Post thinks that Wall Street bankers should get a pass on fraudulently passing off tens of billions in bad mortgage backed securities.

The other point is that executives of large corporations like J.P. Morgan are supposed to understand that when they take over a company it can involve both upside and downside risks. On the upside, the company may have product lines or assets that the buyer did not fully appreciate at the time of the acquisition. On the downside, it may have liabilities such as the legal issues being raised in the Justice Department suit.

Believers in free markets would expect that a CEO like J.P. Morgan’s Jamie Dimon understood such risks at the time he chose to buy up Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual. However the Post apparently feels that he and his bank need a special hand from the government to change the terms of the deal after the fact and release J.P. Morgan from the billions of dollars of liabilities they inherited when they bought the banks. Their concern for the desperate plight of the Wall Street bankers is touching, but those of us who believe in free markets must insist on contracts being respected and laws being enforced.

It is worth noting that J.P. Morgan apparently disagreed with the Post and thought that the government had a pretty good case since it settled for $13 billion.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I spend a lot of time on this blog beating up on the New York Times. There is a reason I pick on them; they are the best. There is no doubt that the NYT is far and away the most important newspaper in the country. There is no close second. They cover more news in more depth than anyone else by a large margin. Their judgments on what is news and how it is reported sets a standard that has an impact, either directly or indirectly, on every news outlet in the country.

For this reason, it is hugely important that the paper has committed itself to reevaluate how it reports budget numbers and to try to put these numbers in contexts that are meaningful to readers. As many polls have shown, the public is hugely misinformed on where their tax dollars are spent. Some of this misinformation undoubtedly reflects prejudices, but much of it is due to the fact that most budget reporting is not providing meaningful information to readers.

Telling readers that the government will spent $195 billion on transportation over the next six years is telling most readers nothing. They have no idea how large $195 billion is to the federal government over the next six years. On the other hand, if the paper reported that this amount is 0.78 percent of projected spending over this period (found in seconds on CEPR’s extraordinary Responsible Budget Calculator) most people would understand the significance of this item to the budget and their tax bill.

Anyhow, we will see exactly how the NYT ends up dealing with the issue, but they deserve a great deal of credit for recognizing the problem and trying to address it. Margaret Sullivan, the paper’s public editor, deserves special credit for taking this one on and pressing it with the paper’s editors. Also Bob Naiman, at Just Foreign Policy, played an important role in initiating a petition at Move-On on this issue, which eventually got almost 19,000 signatures. That’s pretty impressive for the ultimate wonk petition.

Addendum:

Media Matters also deserves serious credit for pushing this issue.

I spend a lot of time on this blog beating up on the New York Times. There is a reason I pick on them; they are the best. There is no doubt that the NYT is far and away the most important newspaper in the country. There is no close second. They cover more news in more depth than anyone else by a large margin. Their judgments on what is news and how it is reported sets a standard that has an impact, either directly or indirectly, on every news outlet in the country.

For this reason, it is hugely important that the paper has committed itself to reevaluate how it reports budget numbers and to try to put these numbers in contexts that are meaningful to readers. As many polls have shown, the public is hugely misinformed on where their tax dollars are spent. Some of this misinformation undoubtedly reflects prejudices, but much of it is due to the fact that most budget reporting is not providing meaningful information to readers.

Telling readers that the government will spent $195 billion on transportation over the next six years is telling most readers nothing. They have no idea how large $195 billion is to the federal government over the next six years. On the other hand, if the paper reported that this amount is 0.78 percent of projected spending over this period (found in seconds on CEPR’s extraordinary Responsible Budget Calculator) most people would understand the significance of this item to the budget and their tax bill.

Anyhow, we will see exactly how the NYT ends up dealing with the issue, but they deserve a great deal of credit for recognizing the problem and trying to address it. Margaret Sullivan, the paper’s public editor, deserves special credit for taking this one on and pressing it with the paper’s editors. Also Bob Naiman, at Just Foreign Policy, played an important role in initiating a petition at Move-On on this issue, which eventually got almost 19,000 signatures. That’s pretty impressive for the ultimate wonk petition.

Addendum:

Media Matters also deserves serious credit for pushing this issue.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Actually, it didn’t explicitly say this, but that was the implication of comments from Adam Posen, the head of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. In a top of the hour news segment (sorry, no link), Posen said that the standoff will accelerate the pace at which countries throughout East Asia begin to trade in Chinese yuan instead of dollars. This will reduce demand for dollars, thereby lowering the value of the dollar.

A lower valued dollar will make U.S. exports more competitive in foreign markets. It will also make domestically produced goods more competitive in the United States leading to fewer imports. This will lead to a lower trade deficit, more growth, and jobs.

If we can reduce the trade deficit by one percentage point of GDP (@$165 billion), this would lead to close to 2 million additional jobs. With fiscal policy likely becoming more contractionary as a result of the deficit fighting craze, a lower valued dollar is the only plausible path to increased growth and more jobs in the foreseeable future.

Actually, it didn’t explicitly say this, but that was the implication of comments from Adam Posen, the head of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. In a top of the hour news segment (sorry, no link), Posen said that the standoff will accelerate the pace at which countries throughout East Asia begin to trade in Chinese yuan instead of dollars. This will reduce demand for dollars, thereby lowering the value of the dollar.

A lower valued dollar will make U.S. exports more competitive in foreign markets. It will also make domestically produced goods more competitive in the United States leading to fewer imports. This will lead to a lower trade deficit, more growth, and jobs.

If we can reduce the trade deficit by one percentage point of GDP (@$165 billion), this would lead to close to 2 million additional jobs. With fiscal policy likely becoming more contractionary as a result of the deficit fighting craze, a lower valued dollar is the only plausible path to increased growth and more jobs in the foreseeable future.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post article on the budget agreement told readers:

“Senate Budget Committee Chairman Patty Murray (D-Wash.) was to have breakfast Thursday morning with her House counterpart, Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), to start a new round of talks aimed at averting another crisis. Obama repeated his vow to work with Republicans to rein in a national debt that remains at historically high levels.

It obviously felt it necessary to the not especially accurate tidbit that the debt remains at historically high levels. (It was considerably higher immediately after World War II.) Since the Post is playing the game of adding in random pieces of information, it could have equally well ended this this sentence by telling readers that efforts at deficit reduction came in spite of the fact that the ratio of interest to GDP is at historically low levels at 1.5 percent of GDP. While this ratio is projected to rise (because of projections of higher interest rates), in a decade we will just be getting back to the interest share of GDP we saw in the early 1990s.

Also, since the Fed is refunding roughly $80 billion a year from its asset holdings, the true interest burden to the Treasury is less than 1.0 percent of GDP. The Fed is projected to reduce its asset holdings and therefore the size of this refund later in the decade, but that is a policy choice. If the Fed feels the need to pull out reserves to raise interest rates and slow the economy, it can also accomplish this by raising reserve requirements for banks. It may opt not to go this route, but if the concern is that interest payments will be a serious burden, this is a problem that could be easily avoided.

The Post could have also ended the sentence by pointing out that this focus on deficit reduction was occurring in spite of the fact that the economy is still down almost 9 million jobs from its trend levels of employment.

The Washington Post article on the budget agreement told readers:

“Senate Budget Committee Chairman Patty Murray (D-Wash.) was to have breakfast Thursday morning with her House counterpart, Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), to start a new round of talks aimed at averting another crisis. Obama repeated his vow to work with Republicans to rein in a national debt that remains at historically high levels.

It obviously felt it necessary to the not especially accurate tidbit that the debt remains at historically high levels. (It was considerably higher immediately after World War II.) Since the Post is playing the game of adding in random pieces of information, it could have equally well ended this this sentence by telling readers that efforts at deficit reduction came in spite of the fact that the ratio of interest to GDP is at historically low levels at 1.5 percent of GDP. While this ratio is projected to rise (because of projections of higher interest rates), in a decade we will just be getting back to the interest share of GDP we saw in the early 1990s.

Also, since the Fed is refunding roughly $80 billion a year from its asset holdings, the true interest burden to the Treasury is less than 1.0 percent of GDP. The Fed is projected to reduce its asset holdings and therefore the size of this refund later in the decade, but that is a policy choice. If the Fed feels the need to pull out reserves to raise interest rates and slow the economy, it can also accomplish this by raising reserve requirements for banks. It may opt not to go this route, but if the concern is that interest payments will be a serious burden, this is a problem that could be easily avoided.

The Post could have also ended the sentence by pointing out that this focus on deficit reduction was occurring in spite of the fact that the economy is still down almost 9 million jobs from its trend levels of employment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a column by Topher Spiro which defended the medical device tax. The column neglected to give the main rationale for the tax, it will recoup some of the excess profits that the industry will accrue as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

The logic here is fairly straightforward, medical devices are like prescription drugs, they can cost a lot to develop, but are cheap to produce. Companies get back their research costs by charging prices that are far above their production costs, which they are able to do as a result of patent monopolies.

To take a simple example, suppose a medical device company has a new screening device that it sells for $1 million. It cost $100,000 to manufacture, so it will make $900,000 from each device it sells. Before the ACA it had expected to sell 1000 copies of this screening device. That would gross it $1 billion, or $900 million in excess of its production costs.

As a result of the ACA more people will have access to health care and therefore demand for the screening device will increase. Suppose it were to rise by 10 percent. In this case the industry’s revenue would rise to $1.1 billion and the profit over production costs will increase to $990 million.

Since the industry had not anticipated the ACA when it developed the screener, and had not expected these extra sales, this additional $90 million is pure gravy in the form of unanticipated profits. The logic of the tax is to take away this gravy to limit the windfall that device manufacturers enjoy as a result of the ACA.

It is also worth noting that the corruption cited in Spiro’s column is the predictable result of a situation in which a product sells at price far above its marginal cost as a result of government protection. This is the same problem that we see in the prescription drug industry.

The economist’s solution would be to devise a mechanism for funding research that would allow drugs and medical equipment to be sold in a free market. However because of the power of the affected industries and the dominance of protectionists in national politics, the efficiency of patent protection in these sectors is rarely discussed.

The NYT ran a column by Topher Spiro which defended the medical device tax. The column neglected to give the main rationale for the tax, it will recoup some of the excess profits that the industry will accrue as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

The logic here is fairly straightforward, medical devices are like prescription drugs, they can cost a lot to develop, but are cheap to produce. Companies get back their research costs by charging prices that are far above their production costs, which they are able to do as a result of patent monopolies.

To take a simple example, suppose a medical device company has a new screening device that it sells for $1 million. It cost $100,000 to manufacture, so it will make $900,000 from each device it sells. Before the ACA it had expected to sell 1000 copies of this screening device. That would gross it $1 billion, or $900 million in excess of its production costs.

As a result of the ACA more people will have access to health care and therefore demand for the screening device will increase. Suppose it were to rise by 10 percent. In this case the industry’s revenue would rise to $1.1 billion and the profit over production costs will increase to $990 million.

Since the industry had not anticipated the ACA when it developed the screener, and had not expected these extra sales, this additional $90 million is pure gravy in the form of unanticipated profits. The logic of the tax is to take away this gravy to limit the windfall that device manufacturers enjoy as a result of the ACA.

It is also worth noting that the corruption cited in Spiro’s column is the predictable result of a situation in which a product sells at price far above its marginal cost as a result of government protection. This is the same problem that we see in the prescription drug industry.

The economist’s solution would be to devise a mechanism for funding research that would allow drugs and medical equipment to be sold in a free market. However because of the power of the affected industries and the dominance of protectionists in national politics, the efficiency of patent protection in these sectors is rarely discussed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT should have pointed out this fact in its discussion of the implications of the standoff on the debt. The piece noted the uncertainty created by the standoff and then told readers:

“Any long-term turn away from Treasury bonds would most likely be driven in large part by foreign investors, like the Chinese and Japanese governments, which are some of the biggest holders of Treasury debt. The willingness of these governments to buy bonds has long held down the cost of credit in the United States and helped keep the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.”

It would have been appropriate to point out that the move by the Chinese and Japanese governments away from holding Treasury debt is a longstanding official policy goal of both the Bush and Obama administrations. Both have complained about currency “manipulation” by these governments. The way these governments manipulate their currencies is by buying up U.S. government bonds. This keeps down the value of their currency against the dollar, making their goods relatively more competitive in international markets.

If China and Japan bought fewer U.S. government bonds their currencies would rise against the dollar, making U.S. goods more competitive and increasing net exports. This could lead to millions of jobs in the United States. The NYT should have pointed out this potential positive benefit from the uncertainty created by the debt standoff.

The NYT should have pointed out this fact in its discussion of the implications of the standoff on the debt. The piece noted the uncertainty created by the standoff and then told readers:

“Any long-term turn away from Treasury bonds would most likely be driven in large part by foreign investors, like the Chinese and Japanese governments, which are some of the biggest holders of Treasury debt. The willingness of these governments to buy bonds has long held down the cost of credit in the United States and helped keep the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.”

It would have been appropriate to point out that the move by the Chinese and Japanese governments away from holding Treasury debt is a longstanding official policy goal of both the Bush and Obama administrations. Both have complained about currency “manipulation” by these governments. The way these governments manipulate their currencies is by buying up U.S. government bonds. This keeps down the value of their currency against the dollar, making their goods relatively more competitive in international markets.

If China and Japan bought fewer U.S. government bonds their currencies would rise against the dollar, making U.S. goods more competitive and increasing net exports. This could lead to millions of jobs in the United States. The NYT should have pointed out this potential positive benefit from the uncertainty created by the debt standoff.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión