David Brooks would benefit hugely from a remedial course in grade school arithmetic. It might keep him from saying silly things in his NYT columns like:

“We are now a mature nation with an aging population. Far from being underinstitutionalized, we are bogged down with a bloated political system, a tangled tax code, a byzantine legal code and a crushing debt.”

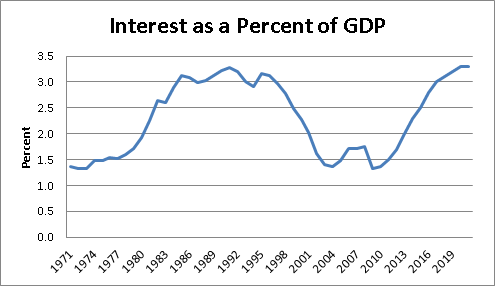

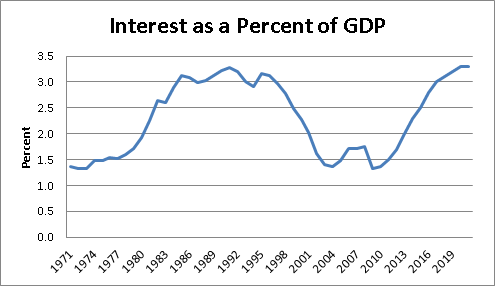

If he were more acquainted with arithmetic he would be able to go to government publications and discover that far from being “crushing,” the interest burden of our debt is near a post-war low. In fact, if we subtracted the $90 billion in interest that is refunded from the Fed to the Treasury the interest burden would be at a post war low.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Brooks’ confusion then causes him to assert:

“Reinvigorating a mature nation means using government to give people the tools to compete, but then opening up a wide field so they do so raucously and creatively. It means spending more here but deregulating more there. It means facing the fact that we do have to choose between the current benefits to seniors and investments in our future, and that to pretend we don’t face that choice, as Obama did, is effectively to sacrifice the future to the past.”

In fact there is no reason to make such a choice between meeting obligations to seniors and investing in the future. If we fixed our health care system so that our per person health care costs were in line with those in other wealthy countries we would be looking at long-term budget surpluses, not deficit.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for calling this one to my attention.

David Brooks would benefit hugely from a remedial course in grade school arithmetic. It might keep him from saying silly things in his NYT columns like:

“We are now a mature nation with an aging population. Far from being underinstitutionalized, we are bogged down with a bloated political system, a tangled tax code, a byzantine legal code and a crushing debt.”

If he were more acquainted with arithmetic he would be able to go to government publications and discover that far from being “crushing,” the interest burden of our debt is near a post-war low. In fact, if we subtracted the $90 billion in interest that is refunded from the Fed to the Treasury the interest burden would be at a post war low.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Brooks’ confusion then causes him to assert:

“Reinvigorating a mature nation means using government to give people the tools to compete, but then opening up a wide field so they do so raucously and creatively. It means spending more here but deregulating more there. It means facing the fact that we do have to choose between the current benefits to seniors and investments in our future, and that to pretend we don’t face that choice, as Obama did, is effectively to sacrifice the future to the past.”

In fact there is no reason to make such a choice between meeting obligations to seniors and investing in the future. If we fixed our health care system so that our per person health care costs were in line with those in other wealthy countries we would be looking at long-term budget surpluses, not deficit.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for calling this one to my attention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Adam Davidson has an interesting piece in the NYT Magazine on the debate over whether technology is responsible for the growth in inequality over the last three decades or whether the increase has been primarily the result of policies that have redistributed income upward. (As the author of The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive, I am firmly in the latter camp.) The immediate basis for the piece is a new paper by Larry Mishel, John Schmitt, and Heidi Shierholz that questions the widely accepted work of M.I.T. professor David Autor, which attributes rising inequality to the loss of jobs in middle class occupations. (The paper is not yet available, but several of the main points are presented in blog posts here, here, here, and here.)

Davidson does a good job laying out the central issues at one point turning to Frank Levy, another M.I.T. economist, to help define the terrain. Levy points out that while inequality has increased almost everywhere, there are huge differences in the extent of the increase. This suggests that there is a very big role for policy in the rise in inequality in the United States. (We’re #1.)

However Davidson’s conclusion may mislead readers.

“What do we value more: growth or fairness? That’s a value judgment. And for better or worse, it’s up to us.”

The idea that there is tradeoff between growth and inequality does not follow from Levy’s comments. It could be the case that policy decisions were aggravating trends in equality rather than alleviating them. For example, increasing the length and scope of patent and copyright protection is a policy that would have the effect of redistributing income upward as would protecting doctors and lawyers from international competition in a context where trade policy is designed to make most workers increasingly exposed to such competition. In these and other cases, it is possible to identify policies that would likely both increase growth and reduce inequality.

Adam Davidson has an interesting piece in the NYT Magazine on the debate over whether technology is responsible for the growth in inequality over the last three decades or whether the increase has been primarily the result of policies that have redistributed income upward. (As the author of The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive, I am firmly in the latter camp.) The immediate basis for the piece is a new paper by Larry Mishel, John Schmitt, and Heidi Shierholz that questions the widely accepted work of M.I.T. professor David Autor, which attributes rising inequality to the loss of jobs in middle class occupations. (The paper is not yet available, but several of the main points are presented in blog posts here, here, here, and here.)

Davidson does a good job laying out the central issues at one point turning to Frank Levy, another M.I.T. economist, to help define the terrain. Levy points out that while inequality has increased almost everywhere, there are huge differences in the extent of the increase. This suggests that there is a very big role for policy in the rise in inequality in the United States. (We’re #1.)

However Davidson’s conclusion may mislead readers.

“What do we value more: growth or fairness? That’s a value judgment. And for better or worse, it’s up to us.”

The idea that there is tradeoff between growth and inequality does not follow from Levy’s comments. It could be the case that policy decisions were aggravating trends in equality rather than alleviating them. For example, increasing the length and scope of patent and copyright protection is a policy that would have the effect of redistributing income upward as would protecting doctors and lawyers from international competition in a context where trade policy is designed to make most workers increasingly exposed to such competition. In these and other cases, it is possible to identify policies that would likely both increase growth and reduce inequality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

What is wrong with people who write opinion pieces for the NYT, they seem to think it is a good thing that people in China are poor. Today Steve Rattner has a column that compares India and China that comments about, “India’s better demographics.” What does this mean, that India maintains rapid population growth, while China has been able to reduce its population growth to a trickle? (A blogpost yesterday had the same complaint about China’s slower population growth.)

Partly as a result of China’s slower population growth there has been a marked tightening of labor markets throughout much of the country. This is allowing hundreds of millions of Chinese workers to have rapidly rising wages which mean rapidly rising living standards. Seeing hundreds of millions of people in a situation to substantially improve their quality of life is a great thing. These people will be protected against hunger and starvation, have decent housing, and be able to provide their kids with education. This is not happening in India to anywhere near the same extent and more rapid population growth is at least part of the story.

In addition to the impact on living standards there is also the impact on the environment. Other things equal, more people means more pollution and more greenhouse gas emissions. Who could want this?

There are plenty of grounds for criticizing China, including some of the mechanisms used to slow population growth, but the slowdown in China’s population growth was an enormous service to humanity.

What is wrong with people who write opinion pieces for the NYT, they seem to think it is a good thing that people in China are poor. Today Steve Rattner has a column that compares India and China that comments about, “India’s better demographics.” What does this mean, that India maintains rapid population growth, while China has been able to reduce its population growth to a trickle? (A blogpost yesterday had the same complaint about China’s slower population growth.)

Partly as a result of China’s slower population growth there has been a marked tightening of labor markets throughout much of the country. This is allowing hundreds of millions of Chinese workers to have rapidly rising wages which mean rapidly rising living standards. Seeing hundreds of millions of people in a situation to substantially improve their quality of life is a great thing. These people will be protected against hunger and starvation, have decent housing, and be able to provide their kids with education. This is not happening in India to anywhere near the same extent and more rapid population growth is at least part of the story.

In addition to the impact on living standards there is also the impact on the environment. Other things equal, more people means more pollution and more greenhouse gas emissions. Who could want this?

There are plenty of grounds for criticizing China, including some of the mechanisms used to slow population growth, but the slowdown in China’s population growth was an enormous service to humanity.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT has an article on how Amgen managed to get a provision into the budget deal signed at the start of this year which could get it $500 million in additional revenue from Medicare over the course of the decade. The piece reports that this was a victory for Amgen’s extensive lobbying network on Capitol Hill.

This sort of corruption is exactly what economic theory predicts when the government gives companies monopolies in certain markets, as it does with patent protected drugs. When a company can sell a drug at prices that are several thousand percent above the marginal cost of production it has enormous incentive to pressure politicians to allow it to sell the drug in contexts where it may not be the best treatment for a disease.

The NYT has an article on how Amgen managed to get a provision into the budget deal signed at the start of this year which could get it $500 million in additional revenue from Medicare over the course of the decade. The piece reports that this was a victory for Amgen’s extensive lobbying network on Capitol Hill.

This sort of corruption is exactly what economic theory predicts when the government gives companies monopolies in certain markets, as it does with patent protected drugs. When a company can sell a drug at prices that are several thousand percent above the marginal cost of production it has enormous incentive to pressure politicians to allow it to sell the drug in contexts where it may not be the best treatment for a disease.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Joe Stiglitz had an Opionator piece in the NYT arguing that inequality was bad for growth. Krugman responded by taking issue with a couple of the points raised by Stiglitz: that upward redistribution of income leads to fiscal problems and that upward redistribution of income leads to stagnation.

On the first point, Krugman correctly notes that the tax code is at least marginally progressive. This means that in general upward redistribution of income should increase revenues, the opposite of what Stiglitz claimed. It is possible that Stiglitz was considering the broader tax and transfer picture. This is certainly more ambiguous and could well go the other way.

Suppose we are redistributing 3 percentage points of income (roughly $400 billion a year) from the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution to the top 2 percent. While tax collections will almost certainly go up, we will likely be paying out more money in food stamps, TANF, Medicaid and other means-tested programs. My guess is the net in this story is negative, but I am sure it would depend on exactly who is being hit and who gets the money.

The more important point is whether we may suffer from a lack of consumption if we redistribute from low income people, who Stiglitz argues will spend most of their income, to rich people who he argues will spend a smaller share of their income. Krugman dismisses this assertion, noting the problem that consumption will depend on lifetime income, not temporary income. This would mean that people will always be spending a higher share of their income when their income is low than when it is high. He then turns to the macro picture to see if there is evidence of a rise in the savings rate as income shifted upwards in the last three decades.

The National Income data of course show a decline in savings, but there is a major complication in this story. The stock market began to rise above its historic average ratio to corporate profits in the 1980s and rose way above the historic ratio in the stock bubble in the 1990s. Also, in the 1990s house prices began to rise above their long-term trend level and in the last decade they rose way above their long-term trend.

We know that people spend based in part on their wealth. The increase in stock values relative to income in the 1980s meant that wealth was higher relative to income than would ordinarily be the case. We would expect this to lead to more consumption and a drop in savings. The same is true with the rise in house prices in the 1990s and 2000s. In other words, we did not have a problem of under-consumption because we had bubbles in the stock and housing markets that kept consumption at very high levels.

Does this prove Stiglitz’s point? I wouldn’t go quite that far, but it does suggest that Krugman’s case is not as solid as it may first appear.

There are two other points worth mentioning on the general topic. The standard savings data would overstate private sector savings in the 70s relative to later decades because of the high inflation of that decade. This eroded the real value of government bonds held by the private sector. That meant that the deficits in that decade were smaller than they appeared, but it also meant that private sector savings was lower than the official data indicate.

The other item to keep in mind is that we are not supposed to be worried about insufficient demand in this story in part because the low interest rates that would result would cause the dollar to fall and net exports to rise. This happened a bit in the mid-90s in response to the deficit reduction of at the beginning of the Clinton administration. However things went the other way following Robert Rubin’s high dollar policy and the East Asian financial crisis.

This is a longer story, but in the textbook story rich countries like the United States are supposed to be net exporters, sending capital to poor countries. The fact that we have seen the opposite in a big way for the last 15 years is not good.

Addendum:

Seth Ackerman reminds me that comparisons of saving rates only make sense when the economy is near full employment. Otherwise the saving rate will be inflated by virtual of the fact that income is depressed lowering the denominator. The full employment assumption is plausible for the late 80s, mid and late 90s, and near the peak of 00s cycle. It is less plausible for the early and mid 80s, early 90s, and early part of the last decade. Of course for comparison purposes, we would have the same issue with the 70s downturn.

Joe Stiglitz had an Opionator piece in the NYT arguing that inequality was bad for growth. Krugman responded by taking issue with a couple of the points raised by Stiglitz: that upward redistribution of income leads to fiscal problems and that upward redistribution of income leads to stagnation.

On the first point, Krugman correctly notes that the tax code is at least marginally progressive. This means that in general upward redistribution of income should increase revenues, the opposite of what Stiglitz claimed. It is possible that Stiglitz was considering the broader tax and transfer picture. This is certainly more ambiguous and could well go the other way.

Suppose we are redistributing 3 percentage points of income (roughly $400 billion a year) from the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution to the top 2 percent. While tax collections will almost certainly go up, we will likely be paying out more money in food stamps, TANF, Medicaid and other means-tested programs. My guess is the net in this story is negative, but I am sure it would depend on exactly who is being hit and who gets the money.

The more important point is whether we may suffer from a lack of consumption if we redistribute from low income people, who Stiglitz argues will spend most of their income, to rich people who he argues will spend a smaller share of their income. Krugman dismisses this assertion, noting the problem that consumption will depend on lifetime income, not temporary income. This would mean that people will always be spending a higher share of their income when their income is low than when it is high. He then turns to the macro picture to see if there is evidence of a rise in the savings rate as income shifted upwards in the last three decades.

The National Income data of course show a decline in savings, but there is a major complication in this story. The stock market began to rise above its historic average ratio to corporate profits in the 1980s and rose way above the historic ratio in the stock bubble in the 1990s. Also, in the 1990s house prices began to rise above their long-term trend level and in the last decade they rose way above their long-term trend.

We know that people spend based in part on their wealth. The increase in stock values relative to income in the 1980s meant that wealth was higher relative to income than would ordinarily be the case. We would expect this to lead to more consumption and a drop in savings. The same is true with the rise in house prices in the 1990s and 2000s. In other words, we did not have a problem of under-consumption because we had bubbles in the stock and housing markets that kept consumption at very high levels.

Does this prove Stiglitz’s point? I wouldn’t go quite that far, but it does suggest that Krugman’s case is not as solid as it may first appear.

There are two other points worth mentioning on the general topic. The standard savings data would overstate private sector savings in the 70s relative to later decades because of the high inflation of that decade. This eroded the real value of government bonds held by the private sector. That meant that the deficits in that decade were smaller than they appeared, but it also meant that private sector savings was lower than the official data indicate.

The other item to keep in mind is that we are not supposed to be worried about insufficient demand in this story in part because the low interest rates that would result would cause the dollar to fall and net exports to rise. This happened a bit in the mid-90s in response to the deficit reduction of at the beginning of the Clinton administration. However things went the other way following Robert Rubin’s high dollar policy and the East Asian financial crisis.

This is a longer story, but in the textbook story rich countries like the United States are supposed to be net exporters, sending capital to poor countries. The fact that we have seen the opposite in a big way for the last 15 years is not good.

Addendum:

Seth Ackerman reminds me that comparisons of saving rates only make sense when the economy is near full employment. Otherwise the saving rate will be inflated by virtual of the fact that income is depressed lowering the denominator. The full employment assumption is plausible for the late 80s, mid and late 90s, and near the peak of 00s cycle. It is less plausible for the early and mid 80s, early 90s, and early part of the last decade. Of course for comparison purposes, we would have the same issue with the 70s downturn.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Two weeks ago the NYT ran a lengthy column by two social scientists, Gary King and Samir Soneji, under the headline “Social Security: It’s Worse Than You Think.” The column warned that the Social Security shortfall will actually be larger than currently projected because life expectancies are increasing more rapidly than the trustees had assumed. I had criticized the piece at the time because, among other things, it took no account of how its claim on improving health might affect other aspects of the program, such as the possibility that it would reduce disability rates, allow people to work later in their lives (many people retire due to health conditions), and reduce health care costs which could lower the amount of money paid to workers in employer provided health insurance which escapes the Social Security tax.

It turns out that King and Soneji’s case on life expectancy is far less compelling than they claim in their column. The actuaries at the Social Security Administration put out a response this week. They pointed out that the King and Soneji methodology is not anything new to them and note several inaccuracies in their column and the paper on which it is based. So it looks like we may not have to worry after all, we are going to die young.

Two weeks ago the NYT ran a lengthy column by two social scientists, Gary King and Samir Soneji, under the headline “Social Security: It’s Worse Than You Think.” The column warned that the Social Security shortfall will actually be larger than currently projected because life expectancies are increasing more rapidly than the trustees had assumed. I had criticized the piece at the time because, among other things, it took no account of how its claim on improving health might affect other aspects of the program, such as the possibility that it would reduce disability rates, allow people to work later in their lives (many people retire due to health conditions), and reduce health care costs which could lower the amount of money paid to workers in employer provided health insurance which escapes the Social Security tax.

It turns out that King and Soneji’s case on life expectancy is far less compelling than they claim in their column. The actuaries at the Social Security Administration put out a response this week. They pointed out that the King and Soneji methodology is not anything new to them and note several inaccuracies in their column and the paper on which it is based. So it looks like we may not have to worry after all, we are going to die young.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post and other news outlets wrote about the release of the transcripts from Federal Reserve Board’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings from 2007. The transcripts are striking with the FOMC members still largely oblivious to the collapse that was taking place around them.

I’ve not read through the whole set of transcripts, which probably exceed 1000 pages, but what is remarkable to me is a seeming complete failure to understand the extent to which the housing market was driving the economy. Housing construction had exceeded 6.0 percent of GDP at the peak of the bubble compared to an average of between 3.0-4.0 percent in the prior three decades. This was not explained by fundamentals. Similarly the saving rate had fallen to nearly zero compared to an average in the pre-stock bubble years of more than 8.0 percent.

The FOMC members were utterly clueless about the extent to which the bubble was driving the economy. It is therefore not surprising that they would be taken aback by the size of the hole created by its collapse. The overbuilding of the bubble years meant that construction would not just fall back to its normal level, but in fact well below as builders allowed excess supply to be filled. (It dropped to around 2.0 percent of GDP, a falloff of more than 4 percentage points.)

Consumption would naturally fall as the housing wealth that was driving it disappeared. The savings rate rose to above 5 percent in the wake of the downturn which corresponds to a loss of demand that is close to 4.0 percentage points of GDP. The combined loss in annual demand from these two sectors was close to 8 percent of GDP ($1.2 trillion in today’s economy).

What did the FOMC members think could replace this lost demand? Housing and consumption together account for three quarters of the economy. There is nothing except the government that could fill a demand gap of this size, at least in the short term. In the longer term, net exports can increase enough to fill a gap of this proportion, but that was not going to happen overnight.

Remarkably, the FOMC folks were not even asking questions like this. That is scary.

The Post and other news outlets wrote about the release of the transcripts from Federal Reserve Board’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings from 2007. The transcripts are striking with the FOMC members still largely oblivious to the collapse that was taking place around them.

I’ve not read through the whole set of transcripts, which probably exceed 1000 pages, but what is remarkable to me is a seeming complete failure to understand the extent to which the housing market was driving the economy. Housing construction had exceeded 6.0 percent of GDP at the peak of the bubble compared to an average of between 3.0-4.0 percent in the prior three decades. This was not explained by fundamentals. Similarly the saving rate had fallen to nearly zero compared to an average in the pre-stock bubble years of more than 8.0 percent.

The FOMC members were utterly clueless about the extent to which the bubble was driving the economy. It is therefore not surprising that they would be taken aback by the size of the hole created by its collapse. The overbuilding of the bubble years meant that construction would not just fall back to its normal level, but in fact well below as builders allowed excess supply to be filled. (It dropped to around 2.0 percent of GDP, a falloff of more than 4 percentage points.)

Consumption would naturally fall as the housing wealth that was driving it disappeared. The savings rate rose to above 5 percent in the wake of the downturn which corresponds to a loss of demand that is close to 4.0 percentage points of GDP. The combined loss in annual demand from these two sectors was close to 8 percent of GDP ($1.2 trillion in today’s economy).

What did the FOMC members think could replace this lost demand? Housing and consumption together account for three quarters of the economy. There is nothing except the government that could fill a demand gap of this size, at least in the short term. In the longer term, net exports can increase enough to fill a gap of this proportion, but that was not going to happen overnight.

Remarkably, the FOMC folks were not even asking questions like this. That is scary.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Wow this is really getting incredible, yet another piece about how China is going to be suffering because it has a declining labor force. The big problem seems to be that we may not be able to count on cheap tee-shirts from China. The prescription is that Chinese people should have more kids so that we can have more cheap labor. The downside is that it will take 20 years before the kids born today will be able to join the labor force.

That is only a slight caricature of the blogpost by the usually insightful Vikas Bajaj. The obsession with the declining labor force in China, and the nearly universal conviction that it is bad, displays a seriously confused view of economics.

Let’s say that China’s labor force declines at the rate of 1 percent annually for the next four decades. So what? This means that the price of labor will rise and the least productive jobs will go unfilled. This is what happened in the United States when people left the farms for better paying jobs in manufacturing. Farmers no doubt felt there was a labor shortage, but that is how market economies work. Less productive businesses go under, do Bajaj and his fellow China worriers want to stop technological progress?

In terms of being able to support a rising population of dependents, it is important to keep productivity growth in this picture. China’s economy had been growing at the rate of 10 percent a year. Even if this slows to 7 percent as many predict, it will allow workers to enjoy much higher after tax income even if an increasing portion of their wage is diverted to supporting China’s elderly population.

The arithmetic here is simple. If wages rise in step with productivity growth, then after 20 years wages will have risen by 287 percent. Even if the tax burden on workers increased by 20 percentage points over this period they would still have far more after-tax income than they had when the dependency rate was lower and the economy was less productive.

What is especially bizarre is that the obsession with the prospect of a declining population takes no notice of the horrible pollution problem that China faces in Beijing and other major cities and also the problem of global warming. A declining population will help to directly address both problems. The fact that China slowed its population growth was an enormous service to humanity.

Wow this is really getting incredible, yet another piece about how China is going to be suffering because it has a declining labor force. The big problem seems to be that we may not be able to count on cheap tee-shirts from China. The prescription is that Chinese people should have more kids so that we can have more cheap labor. The downside is that it will take 20 years before the kids born today will be able to join the labor force.

That is only a slight caricature of the blogpost by the usually insightful Vikas Bajaj. The obsession with the declining labor force in China, and the nearly universal conviction that it is bad, displays a seriously confused view of economics.

Let’s say that China’s labor force declines at the rate of 1 percent annually for the next four decades. So what? This means that the price of labor will rise and the least productive jobs will go unfilled. This is what happened in the United States when people left the farms for better paying jobs in manufacturing. Farmers no doubt felt there was a labor shortage, but that is how market economies work. Less productive businesses go under, do Bajaj and his fellow China worriers want to stop technological progress?

In terms of being able to support a rising population of dependents, it is important to keep productivity growth in this picture. China’s economy had been growing at the rate of 10 percent a year. Even if this slows to 7 percent as many predict, it will allow workers to enjoy much higher after tax income even if an increasing portion of their wage is diverted to supporting China’s elderly population.

The arithmetic here is simple. If wages rise in step with productivity growth, then after 20 years wages will have risen by 287 percent. Even if the tax burden on workers increased by 20 percentage points over this period they would still have far more after-tax income than they had when the dependency rate was lower and the economy was less productive.

What is especially bizarre is that the obsession with the prospect of a declining population takes no notice of the horrible pollution problem that China faces in Beijing and other major cities and also the problem of global warming. A declining population will help to directly address both problems. The fact that China slowed its population growth was an enormous service to humanity.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

You gotta love a guy sitting around thinking of ways to kill a bill that extends health insurance to people who don’t have it and ensures that people who have insurance and then lose their job due to illness, can continue to be insured. That’s what George Will does for a living and he is very happy today because he thinks he has a way to kill the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Will looked at Chief Justice Roberts’ rationale for casting the 5th and deciding vote in support of the constitutionality of the ACA. He says that it rested on the idea that the penalty for not buying insurance was relatively modest. Therefore people might opt to pay the penalty rather than buy insurance, which means it was not actually forcing people to buy insurance. Will argues that this logic will prevent Congress from ever increasing the size of the penalty.

Will then does some arithmetic and points out that for someone earning $100,000 a year the penalty for not buying insurance will be $200 a month whereas a basic insurance policy would cost $400. He then notes that if someone gets seriously ill they could always then opt to buy insurance. Since $200 is less than $400, Will says large numbers of healthy people will opt not to buy insurance. This will force up the price, since the people buying insurance are relatively unhealthy, leading more people to pay the penalty. This will cause more healthy people to opt out and pay the penalty, giving us a wonderful death spiral and making George Will very happy.

There are two problems with Will’s logic. First, the insurance will likely pay for many non-serious illnesses that even healthy people would otherwise have to cover out of pocket. In other words, it is not a question of paying $400 for nothing as opposed to paying $200 for nothing. It is a question of paying $400 for insurance or $200 for nothing. It is not clear that many people will make the choice that Will wants them to make.

The more important problem with Will’s thinking is that there are an endless number of ways to slice and dice the restrictions so that the option of not buying insurance is less attractive. For example, the cost of buying insurance can be made higher for those who had previously opted not to buy into the system. Suppose the cost of later buying into the system rose 25 percent for each year that a person opted not to buy in. (Medicare Part B works this way and the vast majority of beneficiaries do chose to buy in when they first become eligible.) This would make the arithmetic of opting out much less favorable.

The rules can also be changed to make pre-existing conditions uncovered for the first 2 years after buying insurance for those who opted to pay the penalty rather than buy into the system. Neither of these measures would in any obvious way run afoul of Justice Roberts’ argument for the constitutionality of the ACA.

Of course if the Republicans continue to maintain a majority in the House and they are determined to prevent any legislation that can address problems that arise with the ACA, then Will may get his wish and the ACA may be undermined. However that route would have nothing to do with the constitutional restrictions put in place by Roberts. So score this one as a big strikeout for George Will.

You gotta love a guy sitting around thinking of ways to kill a bill that extends health insurance to people who don’t have it and ensures that people who have insurance and then lose their job due to illness, can continue to be insured. That’s what George Will does for a living and he is very happy today because he thinks he has a way to kill the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Will looked at Chief Justice Roberts’ rationale for casting the 5th and deciding vote in support of the constitutionality of the ACA. He says that it rested on the idea that the penalty for not buying insurance was relatively modest. Therefore people might opt to pay the penalty rather than buy insurance, which means it was not actually forcing people to buy insurance. Will argues that this logic will prevent Congress from ever increasing the size of the penalty.

Will then does some arithmetic and points out that for someone earning $100,000 a year the penalty for not buying insurance will be $200 a month whereas a basic insurance policy would cost $400. He then notes that if someone gets seriously ill they could always then opt to buy insurance. Since $200 is less than $400, Will says large numbers of healthy people will opt not to buy insurance. This will force up the price, since the people buying insurance are relatively unhealthy, leading more people to pay the penalty. This will cause more healthy people to opt out and pay the penalty, giving us a wonderful death spiral and making George Will very happy.

There are two problems with Will’s logic. First, the insurance will likely pay for many non-serious illnesses that even healthy people would otherwise have to cover out of pocket. In other words, it is not a question of paying $400 for nothing as opposed to paying $200 for nothing. It is a question of paying $400 for insurance or $200 for nothing. It is not clear that many people will make the choice that Will wants them to make.

The more important problem with Will’s thinking is that there are an endless number of ways to slice and dice the restrictions so that the option of not buying insurance is less attractive. For example, the cost of buying insurance can be made higher for those who had previously opted not to buy into the system. Suppose the cost of later buying into the system rose 25 percent for each year that a person opted not to buy in. (Medicare Part B works this way and the vast majority of beneficiaries do chose to buy in when they first become eligible.) This would make the arithmetic of opting out much less favorable.

The rules can also be changed to make pre-existing conditions uncovered for the first 2 years after buying insurance for those who opted to pay the penalty rather than buy into the system. Neither of these measures would in any obvious way run afoul of Justice Roberts’ argument for the constitutionality of the ACA.

Of course if the Republicans continue to maintain a majority in the House and they are determined to prevent any legislation that can address problems that arise with the ACA, then Will may get his wish and the ACA may be undermined. However that route would have nothing to do with the constitutional restrictions put in place by Roberts. So score this one as a big strikeout for George Will.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión