That’s what readers of a front page piece highlighting Japan’s “decline” would assume. After all, the major facts cited to make the case are a projection that its population would decline from 127 million today to 47 million at the end of the century and that it has the oldest population in the world.

The decline in population might be seen as good news except by those who feel that people exist to give their politicians more power in the world. Japan is a very densely populated country. People are employed to shove commuters into over-crowded subway cars. It is difficult to see why anyone would be concerned if the country becomes less crowded over the course of the century.

In terms of the aging of the population, this is due in part to the fact that Japanese have a life expectancy that is four years longer than the United States. It would have a younger population if its people could only expect to live as long as people in the United States.

In fact, a serious examination of the data does not support the case of a Japan in decline, at least in terms of the living standards of its population. According to the OECD, the average length of the workyear has fallen by almost 15 percent over the last two decades. At the same time, the IMF reports that per capita income has risen by more than one-third. It is difficult to see how this would fit the definition of a nation in decline.

That’s what readers of a front page piece highlighting Japan’s “decline” would assume. After all, the major facts cited to make the case are a projection that its population would decline from 127 million today to 47 million at the end of the century and that it has the oldest population in the world.

The decline in population might be seen as good news except by those who feel that people exist to give their politicians more power in the world. Japan is a very densely populated country. People are employed to shove commuters into over-crowded subway cars. It is difficult to see why anyone would be concerned if the country becomes less crowded over the course of the century.

In terms of the aging of the population, this is due in part to the fact that Japanese have a life expectancy that is four years longer than the United States. It would have a younger population if its people could only expect to live as long as people in the United States.

In fact, a serious examination of the data does not support the case of a Japan in decline, at least in terms of the living standards of its population. According to the OECD, the average length of the workyear has fallen by almost 15 percent over the last two decades. At the same time, the IMF reports that per capita income has risen by more than one-third. It is difficult to see how this would fit the definition of a nation in decline.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post had an interesting idea that went badly awry. It thought to tell its readers what parts of the economy are lagging by comparing the share of GDP in the most recent quarter to the average over the period from 1985 to 2005. While the choice of years is somewhat problematic (in the years 1996-2000 the economy was being supported by an unsustainable stock bubble and in the years 2002-2005 by an unsustainable housing bubble), the bigger problems stem from a failure of arithmetic and also conceptualization.

On the arithmetic front, the piece comes up with a story where consumption of durables is $267 billion below the long-term average, while consumption of non-durables are $127 billion below their long-term average. While it has consumption of services somewhat about the long-term average, the next effect is that weak consumption is a big drag on the economy and accounts for a large share of the shortfall. It tells us:

“Consumers are holding onto their wallets — a continuing burden for the weak economy.”

Wow, that isn’t what the Commerce Department is telling my spreadsheet. I get that the average share of consumption (all categories together) in GDP was 67.3 percent in the years from 1985 to 2005. I get that it was 70.8 percent in the most recent quarter. This means that consumption was 3.5 percent higher than its longer period average as a share of GDP. This means that consumers are not hanging onto their wallets at all. In fact, they are spending at very ambitious rate. (Boys and girls, you can check this one for yourself by going to the National Income and Product Accounts and clicking up Table 1.1.5.)

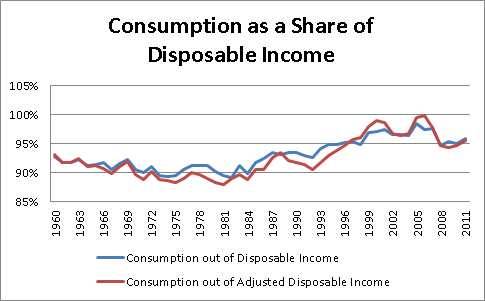

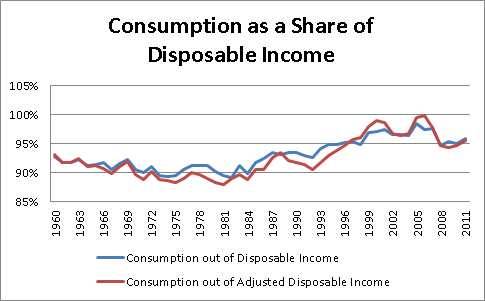

This is consistent with the data showing that consumption is higher than normal relative to disposable income. (The adjusted consumption line has to do with the treatment of the statistical discrepancy in the national income accounts.) This means that consumption is not holding back the economy, it is actually unusually high.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The amount of excess consumption is even more than this comparison suggests, since one reason that consumption is high relative to GDP is that tax revenue is low relative to GDP (i.e. we are running large budget deficits). If the deficit starts to come down, then disposable income will fall relative to GDP, which means that consumption will fall relative to GDP, even if the saving rate stays constant.

The other error along these lines is that imports should be expected to rise relative to GDP as the economy moves back toward its potential. If GDP were to rise by 6 percent to bring it back in line with its potential then imports would rise by roughly 20 percent as much or 1.2 percentage points of GDP. This would make it more clear that the biggest factor that is out of line with our historical experience is the trade deficit. That would be even more clear if we took a longer period as the basis of comparison that was not so distorted by asset bubbles.

Of course given the Washington Post’s unabashed celebration of recent trade agreements its reporters are probably not allowed to call attention to such facts.

The Post had an interesting idea that went badly awry. It thought to tell its readers what parts of the economy are lagging by comparing the share of GDP in the most recent quarter to the average over the period from 1985 to 2005. While the choice of years is somewhat problematic (in the years 1996-2000 the economy was being supported by an unsustainable stock bubble and in the years 2002-2005 by an unsustainable housing bubble), the bigger problems stem from a failure of arithmetic and also conceptualization.

On the arithmetic front, the piece comes up with a story where consumption of durables is $267 billion below the long-term average, while consumption of non-durables are $127 billion below their long-term average. While it has consumption of services somewhat about the long-term average, the next effect is that weak consumption is a big drag on the economy and accounts for a large share of the shortfall. It tells us:

“Consumers are holding onto their wallets — a continuing burden for the weak economy.”

Wow, that isn’t what the Commerce Department is telling my spreadsheet. I get that the average share of consumption (all categories together) in GDP was 67.3 percent in the years from 1985 to 2005. I get that it was 70.8 percent in the most recent quarter. This means that consumption was 3.5 percent higher than its longer period average as a share of GDP. This means that consumers are not hanging onto their wallets at all. In fact, they are spending at very ambitious rate. (Boys and girls, you can check this one for yourself by going to the National Income and Product Accounts and clicking up Table 1.1.5.)

This is consistent with the data showing that consumption is higher than normal relative to disposable income. (The adjusted consumption line has to do with the treatment of the statistical discrepancy in the national income accounts.) This means that consumption is not holding back the economy, it is actually unusually high.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The amount of excess consumption is even more than this comparison suggests, since one reason that consumption is high relative to GDP is that tax revenue is low relative to GDP (i.e. we are running large budget deficits). If the deficit starts to come down, then disposable income will fall relative to GDP, which means that consumption will fall relative to GDP, even if the saving rate stays constant.

The other error along these lines is that imports should be expected to rise relative to GDP as the economy moves back toward its potential. If GDP were to rise by 6 percent to bring it back in line with its potential then imports would rise by roughly 20 percent as much or 1.2 percentage points of GDP. This would make it more clear that the biggest factor that is out of line with our historical experience is the trade deficit. That would be even more clear if we took a longer period as the basis of comparison that was not so distorted by asset bubbles.

Of course given the Washington Post’s unabashed celebration of recent trade agreements its reporters are probably not allowed to call attention to such facts.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steven Greenhouse has a great piece in the NYT reporting on how employers are gaining increasing control over their workers’ hours as a way to minimize costs. The obvious point, which seems to be lost on proponents of workplace flexibility, is that allowing employers to be flexible on their time demands means that workers cannot make plans in their lives. This requires them to be able to make child care and other arrangements on short notice. This is likely a very important factor in the quality of the lives of millions of workers that has received little attention in discussions of economic policy.

Steven Greenhouse has a great piece in the NYT reporting on how employers are gaining increasing control over their workers’ hours as a way to minimize costs. The obvious point, which seems to be lost on proponents of workplace flexibility, is that allowing employers to be flexible on their time demands means that workers cannot make plans in their lives. This requires them to be able to make child care and other arrangements on short notice. This is likely a very important factor in the quality of the lives of millions of workers that has received little attention in discussions of economic policy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

NPR’s Planet Money did a nice piece deflating the nonsense on energy independence. Their crew took the long trip all the way to distant Canada, a country that is energy independent. And, thanks to the fact that they have courageous politicians who are willing to kick environmentalists in the teeth, the free people of Canada only have to pay $4.00 a gallon for gas.

As those of us who took intro economics have tried to explain to the reporters covering the campaign, being energy independent doesn’t mean anything unless we are at war and somehow cut off from foreign oil supplies. (If this is our concern then drilling out our oil and gas now is incredibly stupid. That means that it will not be there if we ever face such a crisis.)

Oil prices are determined on world market just like the prices of wheat and corn. When a drought in Asia sends up the price of wheat, we will pay more for wheat in the United States even though we are a huge net exporter of wheat. And, as the Planet Money crew showed us, when the world price of oil skyrockets people in Canada pay more for gas even though they are energy independent, as would we even if we were energy independent.

This basic fact means that when a candidate says that he/she wants to make the U.S. energy independent, they are actually saying either that they don’t have a clue about economics, or that they think the reporters covering the campaign are so incompetent that they won’t call attention to the fact that they are spewing utter nonsense.

NPR’s Planet Money did a nice piece deflating the nonsense on energy independence. Their crew took the long trip all the way to distant Canada, a country that is energy independent. And, thanks to the fact that they have courageous politicians who are willing to kick environmentalists in the teeth, the free people of Canada only have to pay $4.00 a gallon for gas.

As those of us who took intro economics have tried to explain to the reporters covering the campaign, being energy independent doesn’t mean anything unless we are at war and somehow cut off from foreign oil supplies. (If this is our concern then drilling out our oil and gas now is incredibly stupid. That means that it will not be there if we ever face such a crisis.)

Oil prices are determined on world market just like the prices of wheat and corn. When a drought in Asia sends up the price of wheat, we will pay more for wheat in the United States even though we are a huge net exporter of wheat. And, as the Planet Money crew showed us, when the world price of oil skyrockets people in Canada pay more for gas even though they are energy independent, as would we even if we were energy independent.

This basic fact means that when a candidate says that he/she wants to make the U.S. energy independent, they are actually saying either that they don’t have a clue about economics, or that they think the reporters covering the campaign are so incompetent that they won’t call attention to the fact that they are spewing utter nonsense.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT badly misinterpreted data suggesting that household debt may soon be rising again. The NYT noted the fact that households may be taking on debt again on net and argued that this may presage an uptick in the economy. In fact, it suggests nothing of the sort.

At any point in time tens of millions of households are taking on new debt by buying homes, taking out student loans, borrowing against a credit card or taking out other loans. At the same time, tens of millions of families are reducing their debt, most importantly by paying down mortgages. In addition, much debt is being eliminated as a result of being written off by creditors, mostly through bankruptcy or foreclosure.

The reason that debt has been falling in the last few years has been due to the large amount of debt being written off, primarily as a result of foreclosures. To get an idea of this magnitude, suppose that 1 million homes a year go through the foreclosure process. If we assume an average mortgage of $200,000 a home (roughly the magnitudes involved), this would imply the elimination of $200 billion in debt each year, assuming that the households taking on new debt were just balanced by the households paying off debt. If the number of foreclosures fell in half to 500,000, and nothing else changed, then the rate at which debt was being reduced would fall to $100 billion a year.

This is primarily the story that we are seeing as the pace of debt reduction slows and is possibly reversed. The number of foreclosures is gradually falling, meaning that the pace of debt elimination through this channel is slowing, however this has little direct impact on the economy. (The foreclosure process does employ people and generate incomes.)

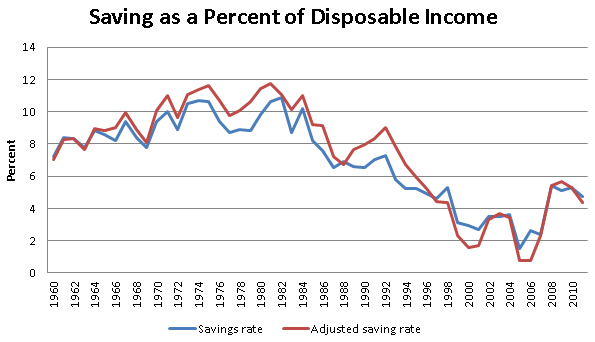

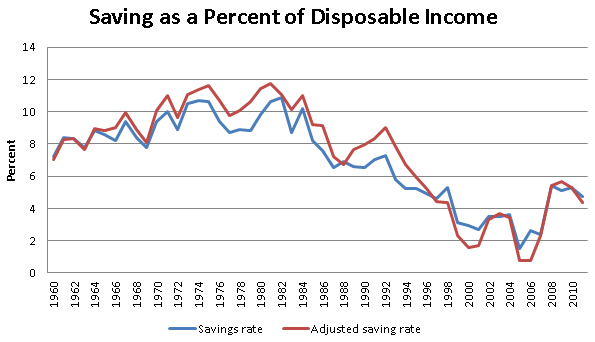

The relevant issue for the economy is the saving rate. While the saving rate is above its near zero level at the peak of the bubble, it has been below its long-term average throughout the downturn. (The adjusted saving rate is a nerd issue having to do with the statistical discrepancy in the national accounts.)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The 3.7 percent rate for the third quarter is well below the pre-bubble average of more than 8.0 percent. It would be surprising if the saving rate would fall still lower since most households have very little wealth saved for retirement and the leadership of both parties is proposing cuts in Social Security and Medicare. In short, there is no reason to expect that an upturn in consumption will provide a boost to the economy.

The NYT badly misinterpreted data suggesting that household debt may soon be rising again. The NYT noted the fact that households may be taking on debt again on net and argued that this may presage an uptick in the economy. In fact, it suggests nothing of the sort.

At any point in time tens of millions of households are taking on new debt by buying homes, taking out student loans, borrowing against a credit card or taking out other loans. At the same time, tens of millions of families are reducing their debt, most importantly by paying down mortgages. In addition, much debt is being eliminated as a result of being written off by creditors, mostly through bankruptcy or foreclosure.

The reason that debt has been falling in the last few years has been due to the large amount of debt being written off, primarily as a result of foreclosures. To get an idea of this magnitude, suppose that 1 million homes a year go through the foreclosure process. If we assume an average mortgage of $200,000 a home (roughly the magnitudes involved), this would imply the elimination of $200 billion in debt each year, assuming that the households taking on new debt were just balanced by the households paying off debt. If the number of foreclosures fell in half to 500,000, and nothing else changed, then the rate at which debt was being reduced would fall to $100 billion a year.

This is primarily the story that we are seeing as the pace of debt reduction slows and is possibly reversed. The number of foreclosures is gradually falling, meaning that the pace of debt elimination through this channel is slowing, however this has little direct impact on the economy. (The foreclosure process does employ people and generate incomes.)

The relevant issue for the economy is the saving rate. While the saving rate is above its near zero level at the peak of the bubble, it has been below its long-term average throughout the downturn. (The adjusted saving rate is a nerd issue having to do with the statistical discrepancy in the national accounts.)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The 3.7 percent rate for the third quarter is well below the pre-bubble average of more than 8.0 percent. It would be surprising if the saving rate would fall still lower since most households have very little wealth saved for retirement and the leadership of both parties is proposing cuts in Social Security and Medicare. In short, there is no reason to expect that an upturn in consumption will provide a boost to the economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT deserves credit for pointing out the personal interest of a group of corporate CEOs in the outcome of negotiations over the budget. An article on the Campaign to Fix the Debt reminded readers that:

“several members of the group, which includes highly paid chief executives of financial and industrial corporations who will stand to pay more if President Obama succeeds in his effort to raise taxes on the wealthy…”

By contrast, the Post ran an article on the same group last week that never noted the personal interest of the individuals involved, instead treating them entirely as a civically minded group focused on the country’s future.

The NYT deserves credit for pointing out the personal interest of a group of corporate CEOs in the outcome of negotiations over the budget. An article on the Campaign to Fix the Debt reminded readers that:

“several members of the group, which includes highly paid chief executives of financial and industrial corporations who will stand to pay more if President Obama succeeds in his effort to raise taxes on the wealthy…”

By contrast, the Post ran an article on the same group last week that never noted the personal interest of the individuals involved, instead treating them entirely as a civically minded group focused on the country’s future.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Regular Washington Post readers know that the paper has long since abandoned the separation of news and opinion when it comes to promoting its views on Social Security, Medicare and the budget deficit. It again displayed its disdain for normal journalistic integrity with a front page piece trumpeting a study from National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) that warned of the dire consequences from the “fiscal cliff,” the Post’s sensationalist term for the scheduled ending of tax cuts and sequestration of spending at the end of the year.

The headline of the piece told readers that “‘fiscal cliff’ already hurting economy, report says.” While the article excludes the views of anyone who questioned the claims presented by NAM and its study, many of their assertions are implausible on their face. For example, the first sentence tells readers:

“The ‘fiscal cliff’ is still two months off, but the scheduled blast of tax hikes and spending cuts is already reverberating through the U.S. economy, hampering growth and, according to a new study, wiping out nearly 1 million jobs this year alone.”

This would correspond to a reduction in GDP growth for the year of approximately 0.7 percent. Presumably this falloff is all occurring in the 3rd and 4th quarter. (The Post and other news outlets would have been incredibly negligent if they had failed to report this extraordinary drag on growth in the first half of the year, if it were true.) That means that we are seeing a drag on GDP growth of approximately 1.5 percentage points of GDP in the second half of this year due to the concern over the tax and spending changes at the end of the year. In other words, the Post is telling us that GDP would be growing at around a 3.5 percent annual rate right now if not for the budget deal reached last summer. It would be interesting if they could find an economist not on the payroll of the NAM who would say something like this.

In presenting its list of horror stories about the budget situation the Post tells readers about Mike Kelly, the president and chief executive of Nanocerox, a defense contractor. The Post tells us that he claims to have “embarked on an aggressive cost-containment strategy nine months ago… laid off four of his 22 employees and converted them to contract workers, froze salaries, renegotiated health benefits and tightened controls on spending.”

Of course this may be due to the fact there are likely to be cutbacks in the military budget regardless of how the current budget dispute is resolved. In other words, these cutbacks may have nothing to do with the budget battles themselves but rather stem from Mr. Kelly’s assessment that Congress is likely to reduce funding for his product. These are exactly the sorts of cutbacks that advocates of deficit reduction want since they free up capital and labor for other purposes. The Post should have included the views of an advocate of lower deficits who could have pointed this fact out to readers.

The article also highlights the weakness in orders for new capital goods in recent months. This is likely related to uncertainty, but not necessarily of the sort implied by the Post. The tax treatment of investment is up for grabs in the current budget battles. It is possible that investment goods will be taxed at either a higher or lower rate in 2013. If businesses anticipate that the outcome of a deal will allow for a lower tax rate on new investment (for example expensing of capital goods), then they would have good reason to defer investment until after the budget dispute is resolved. While this may affect the timing of investment decisions, its net effect on the economy is likely to be minimal.

At one point the Post article referred to a call for tax increases and spending cuts by a number of CEOs which it described “as part of a long-term plan to tame the $16.2 trillion national debt. “Tame” is a word that is appropriate to dealing with wild animals. Newspapers would use terms like “limit” or “reduce” in reference to the debt.

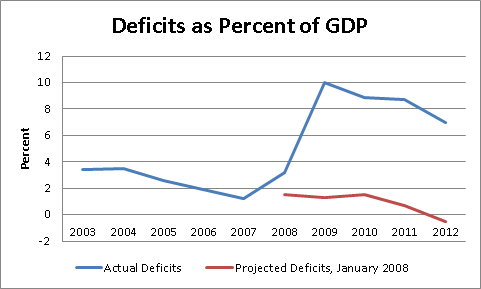

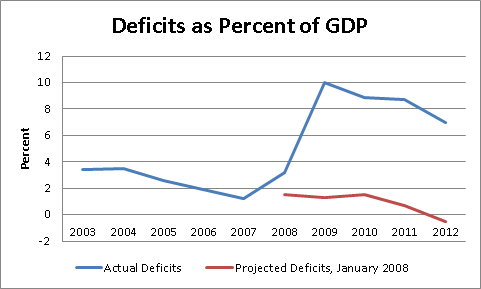

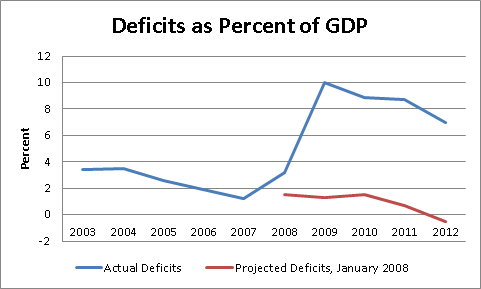

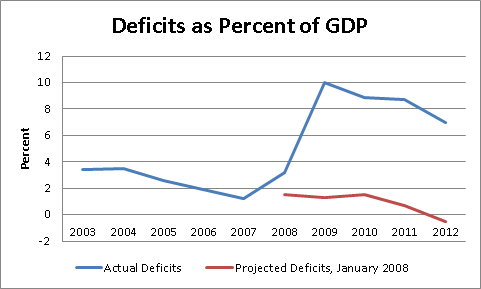

This comment also may lead to the misleading view that the deficit has been a longstanding problem. In fact the deficits had just before the downturn had been fairly modest and were projected to remain modest long into the future. The reason that the deficits exploded was that economy collapsed as a result of the bursting of the housing bubble.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Finally, the Post never points out that the dire projections for a recession and a sharp uptick in unemployment assume that the higher taxes and lower rate of spending are left in place all year. These are not the predicted results of letting them take effect for a few days in January.

Regular Washington Post readers know that the paper has long since abandoned the separation of news and opinion when it comes to promoting its views on Social Security, Medicare and the budget deficit. It again displayed its disdain for normal journalistic integrity with a front page piece trumpeting a study from National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) that warned of the dire consequences from the “fiscal cliff,” the Post’s sensationalist term for the scheduled ending of tax cuts and sequestration of spending at the end of the year.

The headline of the piece told readers that “‘fiscal cliff’ already hurting economy, report says.” While the article excludes the views of anyone who questioned the claims presented by NAM and its study, many of their assertions are implausible on their face. For example, the first sentence tells readers:

“The ‘fiscal cliff’ is still two months off, but the scheduled blast of tax hikes and spending cuts is already reverberating through the U.S. economy, hampering growth and, according to a new study, wiping out nearly 1 million jobs this year alone.”

This would correspond to a reduction in GDP growth for the year of approximately 0.7 percent. Presumably this falloff is all occurring in the 3rd and 4th quarter. (The Post and other news outlets would have been incredibly negligent if they had failed to report this extraordinary drag on growth in the first half of the year, if it were true.) That means that we are seeing a drag on GDP growth of approximately 1.5 percentage points of GDP in the second half of this year due to the concern over the tax and spending changes at the end of the year. In other words, the Post is telling us that GDP would be growing at around a 3.5 percent annual rate right now if not for the budget deal reached last summer. It would be interesting if they could find an economist not on the payroll of the NAM who would say something like this.

In presenting its list of horror stories about the budget situation the Post tells readers about Mike Kelly, the president and chief executive of Nanocerox, a defense contractor. The Post tells us that he claims to have “embarked on an aggressive cost-containment strategy nine months ago… laid off four of his 22 employees and converted them to contract workers, froze salaries, renegotiated health benefits and tightened controls on spending.”

Of course this may be due to the fact there are likely to be cutbacks in the military budget regardless of how the current budget dispute is resolved. In other words, these cutbacks may have nothing to do with the budget battles themselves but rather stem from Mr. Kelly’s assessment that Congress is likely to reduce funding for his product. These are exactly the sorts of cutbacks that advocates of deficit reduction want since they free up capital and labor for other purposes. The Post should have included the views of an advocate of lower deficits who could have pointed this fact out to readers.

The article also highlights the weakness in orders for new capital goods in recent months. This is likely related to uncertainty, but not necessarily of the sort implied by the Post. The tax treatment of investment is up for grabs in the current budget battles. It is possible that investment goods will be taxed at either a higher or lower rate in 2013. If businesses anticipate that the outcome of a deal will allow for a lower tax rate on new investment (for example expensing of capital goods), then they would have good reason to defer investment until after the budget dispute is resolved. While this may affect the timing of investment decisions, its net effect on the economy is likely to be minimal.

At one point the Post article referred to a call for tax increases and spending cuts by a number of CEOs which it described “as part of a long-term plan to tame the $16.2 trillion national debt. “Tame” is a word that is appropriate to dealing with wild animals. Newspapers would use terms like “limit” or “reduce” in reference to the debt.

This comment also may lead to the misleading view that the deficit has been a longstanding problem. In fact the deficits had just before the downturn had been fairly modest and were projected to remain modest long into the future. The reason that the deficits exploded was that economy collapsed as a result of the bursting of the housing bubble.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Finally, the Post never points out that the dire projections for a recession and a sharp uptick in unemployment assume that the higher taxes and lower rate of spending are left in place all year. These are not the predicted results of letting them take effect for a few days in January.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post has long given up any pretense of objectivity in its news section on issues like Social Security, Medicare and the budget deficit. It routinely hypes deficit as a problem in a way that is inconsistent with the data and make assertions about the cost trajectory of Social Security and Medicare that are at least misleading, if not actually wrong.

In keeping with this pattern, the Post began an article reporting on an interview that President Obama had with the Des Moines Register by referring to the “the nation’s intractable budget problems.” Of course the nation’s budget problems are not “intractable.” The large deficits came about entirely because of the economic plunge following the collapse of the housing bubble as fans of Congressional Budget Office projections well know.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

As can be seen the deficits were relatively modest until the economy collapsed in 2008 and were projected to remain modest well into the future. The debt to GDP ratio had been falling, which means deficits of this size could be sustained forever. This was true even if the Bush tax cuts did not expire at the end of 2010, although the budget was actually projected to turn to surplus in fiscal 2012 if the tax cuts did expire. It is also worth noting that the interest burden as a percent of GDP, at 1.6 percent, is near a post-war low, so the deficit is not currently presenting a problem to the economy in any obvious way.

The evidence is quite clear, the problem is a collapsed economy which has led to tens of millions of people being unemployed or underemployed. This has also led to much higher deficits. Rather than being a problem, these deficits are supporting demand right now, since there is no private sector demand to replace the $1.2 trillion in annual demand that was generated by the housing bubble.

Those advocating lower deficits in the current economic environment are advocating slower growth and higher unemployment. The fact that these people enjoy considerable political power and access to the media can be viewed as an intractable problem.

The Washington Post has long given up any pretense of objectivity in its news section on issues like Social Security, Medicare and the budget deficit. It routinely hypes deficit as a problem in a way that is inconsistent with the data and make assertions about the cost trajectory of Social Security and Medicare that are at least misleading, if not actually wrong.

In keeping with this pattern, the Post began an article reporting on an interview that President Obama had with the Des Moines Register by referring to the “the nation’s intractable budget problems.” Of course the nation’s budget problems are not “intractable.” The large deficits came about entirely because of the economic plunge following the collapse of the housing bubble as fans of Congressional Budget Office projections well know.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

As can be seen the deficits were relatively modest until the economy collapsed in 2008 and were projected to remain modest well into the future. The debt to GDP ratio had been falling, which means deficits of this size could be sustained forever. This was true even if the Bush tax cuts did not expire at the end of 2010, although the budget was actually projected to turn to surplus in fiscal 2012 if the tax cuts did expire. It is also worth noting that the interest burden as a percent of GDP, at 1.6 percent, is near a post-war low, so the deficit is not currently presenting a problem to the economy in any obvious way.

The evidence is quite clear, the problem is a collapsed economy which has led to tens of millions of people being unemployed or underemployed. This has also led to much higher deficits. Rather than being a problem, these deficits are supporting demand right now, since there is no private sector demand to replace the $1.2 trillion in annual demand that was generated by the housing bubble.

Those advocating lower deficits in the current economic environment are advocating slower growth and higher unemployment. The fact that these people enjoy considerable political power and access to the media can be viewed as an intractable problem.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Nicholas Kristoff uses his column to take a shot at Mitt Romney’s economic policies. While the basic point, that austerity will lead to slower growth and higher unemployment, is correct, placing Germany as a basket case alongside the U.K. is not. While the U.K. has aggressively cut its budget deficit, Germany has not been as ambitious in this respect. (Its deficit had not been as large.)

Germany is primarily feeling the effects of budget cuts in the other euro zone countries, which are largely coming at its own insistence. In this case, Germany is in the same sort of situation as Ohio would be if Pennsylvania, Michigan and Ohio’s economy all went into recession. The effect has been to sharply slow Germany’s growth, although since the start of the recession, Germany’s growth has been roughly equal to that of the United States (somewhat higher on a per capita basis). By contrast, the U.K. has seen sharply lower growth, its economy is still smaller than it was before the downturn began.

In spite of having comparable growth, the unemployment rate in Germany is more than 2 full percentage points below its pre-recession level. By contrast, the unemployment rate in the United States is 3.3 percentage points above its pre-recession level. The difference is that Germany encourages employers to reduce workers’ hours rather than lay them off. The result is that many workers are putting in fewer hours, but still have jobs in Germany. The government makes up for most of the lost pay with money that would otherwise have gone to unemployment benefits.

While close to half of the states have work sharing programs as part of their unemployment insurance program, the take-up rate is very low. The Obama administration has attempted to increase take-up by having the federal government pick up the cost for the next two years. (This measure was attached to the bill that extended the payroll tax cut.) However, because most state budgets are so flush, there has been little interest in getting this money from the federal government.

[Addendum: The comment about flush state budgets is a joke. I can’t imagine why cash strapped states wouldn’t look to get free money from the Feds. I suspect inertia, which is by far the most important force in politics and policy.]

Nicholas Kristoff uses his column to take a shot at Mitt Romney’s economic policies. While the basic point, that austerity will lead to slower growth and higher unemployment, is correct, placing Germany as a basket case alongside the U.K. is not. While the U.K. has aggressively cut its budget deficit, Germany has not been as ambitious in this respect. (Its deficit had not been as large.)

Germany is primarily feeling the effects of budget cuts in the other euro zone countries, which are largely coming at its own insistence. In this case, Germany is in the same sort of situation as Ohio would be if Pennsylvania, Michigan and Ohio’s economy all went into recession. The effect has been to sharply slow Germany’s growth, although since the start of the recession, Germany’s growth has been roughly equal to that of the United States (somewhat higher on a per capita basis). By contrast, the U.K. has seen sharply lower growth, its economy is still smaller than it was before the downturn began.

In spite of having comparable growth, the unemployment rate in Germany is more than 2 full percentage points below its pre-recession level. By contrast, the unemployment rate in the United States is 3.3 percentage points above its pre-recession level. The difference is that Germany encourages employers to reduce workers’ hours rather than lay them off. The result is that many workers are putting in fewer hours, but still have jobs in Germany. The government makes up for most of the lost pay with money that would otherwise have gone to unemployment benefits.

While close to half of the states have work sharing programs as part of their unemployment insurance program, the take-up rate is very low. The Obama administration has attempted to increase take-up by having the federal government pick up the cost for the next two years. (This measure was attached to the bill that extended the payroll tax cut.) However, because most state budgets are so flush, there has been little interest in getting this money from the federal government.

[Addendum: The comment about flush state budgets is a joke. I can’t imagine why cash strapped states wouldn’t look to get free money from the Feds. I suspect inertia, which is by far the most important force in politics and policy.]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Adam Davidson’s NYT magazine piece featured the views of a number of economists as to what the U.S. economy will look like at the time of the next presidential election in 2016. Two of the experts seem to be describing a world in which the United States has become increasingly protectionist:

“by 2016, Frieden and Bremmer noted [Jeffrey Frieden, a professor at Harvard and Ian Bremmer, president of the Eurasia Group], the U.S. will be adjusting to an economy in which inequality is a structural fixture. There will be millions who are unable to get work, and tens of millions more who will have to adapt to lower income. Meanwhile, those with college and advanced degrees will experience a country that has rebounded. Their incomes will grow.”

Of course the main reason that workers at the top of the income distribution have seen their wages rise is that they continue to be largely protected from international competition. Our doctors are paid roughly twice as much as their counterparts in wealthy countries like Canada and Germany and several times as much as doctors in India, China and elsewhere in the developing world. Doctors from these countries would be happy to train to U.S. standards and work for half the pay that U.S. doctors receive, but are prevented from competing with our doctors by professional barriers. If protectionists did not dominate economic policy, the country could save hundreds of billions of dollars each year in health care costs and in the cost of other highly paid professional services. Frieden and Bremmer may well be right that protectionists will continue to control policy due to their outsized political power, but it is worth noting that this is political outcome, not a result driven by economics. (It is worth noting that rising wages for college grads would be a change. They have seen stagnant or declining wages over the last decade.)

It is also worth noting that the growth story in this piece might not prove accurate. It points to foreign pharmaceutical sales as a major growth sector for the U.S. economy, noting that the domestic market is likely to diminish in importance. This is very questionable. Drugs are actually very cheap. There are few drugs that would sell for more than $10 in a free market. The reason that drugs are expensive is because of patent protection and other restrictions on competition such as data exclusivity.

The United States has been able to get other countries to accept these extremely costly forms of protection as a quid pro quo for gaining access to the U.S. domestic market. However if the U.S. domestic market is no longer seen as a big prize internationally (a main thesis of the piece), then other countries are unlikely to go along with paying U.S. drug companies patent protected prices. There would be no offsetting gain to compensate for this huge drain on foreign economies.

It is also worth noting that the main reason that we have a dispute over currency values with China is because they want to be able to sell their goods at a low cost in the U.S. market. If China no longer cares about the U.S. market as a main export destination for their goods, it will presumably have no objection to the value of the dollar dropping against the yuan. This should be a boon for the manufacturing sector in the United States since it will mean that our goods are far more competitive in the world economy.

The piece also says that China will probably not surpass the size of the U.S. economy until the 2020s. The latest projections from the I.M.F. show China’s economy exceeding the size of the U.S. economy on a purchasing power parity basis by 2017.

Adam Davidson’s NYT magazine piece featured the views of a number of economists as to what the U.S. economy will look like at the time of the next presidential election in 2016. Two of the experts seem to be describing a world in which the United States has become increasingly protectionist:

“by 2016, Frieden and Bremmer noted [Jeffrey Frieden, a professor at Harvard and Ian Bremmer, president of the Eurasia Group], the U.S. will be adjusting to an economy in which inequality is a structural fixture. There will be millions who are unable to get work, and tens of millions more who will have to adapt to lower income. Meanwhile, those with college and advanced degrees will experience a country that has rebounded. Their incomes will grow.”

Of course the main reason that workers at the top of the income distribution have seen their wages rise is that they continue to be largely protected from international competition. Our doctors are paid roughly twice as much as their counterparts in wealthy countries like Canada and Germany and several times as much as doctors in India, China and elsewhere in the developing world. Doctors from these countries would be happy to train to U.S. standards and work for half the pay that U.S. doctors receive, but are prevented from competing with our doctors by professional barriers. If protectionists did not dominate economic policy, the country could save hundreds of billions of dollars each year in health care costs and in the cost of other highly paid professional services. Frieden and Bremmer may well be right that protectionists will continue to control policy due to their outsized political power, but it is worth noting that this is political outcome, not a result driven by economics. (It is worth noting that rising wages for college grads would be a change. They have seen stagnant or declining wages over the last decade.)

It is also worth noting that the growth story in this piece might not prove accurate. It points to foreign pharmaceutical sales as a major growth sector for the U.S. economy, noting that the domestic market is likely to diminish in importance. This is very questionable. Drugs are actually very cheap. There are few drugs that would sell for more than $10 in a free market. The reason that drugs are expensive is because of patent protection and other restrictions on competition such as data exclusivity.

The United States has been able to get other countries to accept these extremely costly forms of protection as a quid pro quo for gaining access to the U.S. domestic market. However if the U.S. domestic market is no longer seen as a big prize internationally (a main thesis of the piece), then other countries are unlikely to go along with paying U.S. drug companies patent protected prices. There would be no offsetting gain to compensate for this huge drain on foreign economies.

It is also worth noting that the main reason that we have a dispute over currency values with China is because they want to be able to sell their goods at a low cost in the U.S. market. If China no longer cares about the U.S. market as a main export destination for their goods, it will presumably have no objection to the value of the dollar dropping against the yuan. This should be a boon for the manufacturing sector in the United States since it will mean that our goods are far more competitive in the world economy.

The piece also says that China will probably not surpass the size of the U.S. economy until the 2020s. The latest projections from the I.M.F. show China’s economy exceeding the size of the U.S. economy on a purchasing power parity basis by 2017.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión