Haiti: Relief and Reconstruction Watch is a blog that tracks multinational aid efforts in Haiti with an eye towards ensuring they are oriented towards the needs of the Haitian people, and that aid is not used to undermine Haitians' right to self-determination.

• HaitiHaitiLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

On Friday, November 6, the Haitian government published in Le Moniteur a new decree limiting the powers of the Superior Court of Auditors and Administrative Disputes (CSCCA). The decree itself was signed by the president and ministers nearly two months earlier, on September 9, but was not formally made public until this past weekend. The court, one of only a handful of nominally independent government institutions, is responsible for reviewing draft government contracts as well as conducting audits. While its functions and title have been altered over time, the court was first established in 1823, and was only completely eliminated during the 19-year US occupation of Haiti. It was reestablished afterward and enshrined in the 1987 constitution.

President Moïse has ruled by decree, which is not formally allowed by the Haitian constitution, since January 2020, when the terms of most of parliament expired. He has extended executive powers, reforming the penal code, naming a new electoral council with a mandate to reform the constitution, and now weakening one of the last remaining institutions exercising government oversight. The latest decree follows years of conflict between the CSCCA and the Haitian presidency.

In 2018, anticorruption protesters began advocating for an investigation into Moïse and his predecessors’ handling of billions in Petrocaribe-related spending. Moïse, under increasing pressure from the streets, pledged to support such an investigation. The CSCCA has since released three audit reports on Petrocaribe, finding widespread irregularities and fraudulent practices in the management of the Venezuelan-led aid program, and directly implicating the president, and the company he led before his election. Last year, members of the court had to temporarily leave the country due to threats. As of yet, there has been no real judicial progress in holding anyone accountable for the misuse of public funds. The president has denied all the CSCCA’s allegations.

The conflict has extended beyond just the Petrocaribe investigation, however. In June, the court raised questions over a contract to provide the presidency with helicopters, which had gone to a close political ally. The same month, the CSCCA was accused of hampering the response to COVID when it identified irregularities in a number of contracts to provide the health ministry with face masks awarded under a state of emergency exception. The contracts, worth about $10 million, moved forward despite the concerns — which included companies that had no experience in the sector and one which was owned by the wife of a current minister in the government. The health emergency “served as a pretext … to accelerate the corruption machine,” according to The Center of Analysis and Research in Human Rights (CARDH). The organization found that $34 million in emergency spending had bypassed CSCCA review all together.

In late August, the court blocked a $57 million no-bid government contract with the US company, General Electric, and asked the government to make needed corrections. The president has held the deal up as a key to his pledge to provide electricity across the country. According to the court, one reason for the court’s delay in approving the GE contract was the presence of unknown subcontractors that were to be paid a portion of the total amount.

On September 6, Moïse held a “community dialogue” at the National Palace, where he declared that it would be necessary to “reform” the CSCCA. Public works minister Joacéus Nader went so far as to say the court was blocking progress in the country, and referred to its independent judges as “ignorant” and “incompetent.”

In response to comments made by Moïse, the court issued a five-page statement outlining a series of acts of intimidation and threats on its members. The court also provided some of the reasons why it had not approved contracts. “How is the Court responsible for the invalidity of this draft contract? Where are the blocking acts? Who is blocking whom, or who is blocking what?” the court asked.

Prime Minister Joseph Jouthe attempted to ease tensions, apologizing just days later on Nader’s behalf, and telling Haitian daily Le Nouvelliste that while it was possible to remove bottlenecks in contract processing, changes would not be made without the court’s involvement. We now know that by the time of Jouthe’s apology, the government had already drafted and signed the decree curtailing the court’s powers — but it had not yet been made public.

Two weeks after Jouthe’s apology, Nader appeared at the CSCCA’s offices in Petionville, claiming he and the large group he arrived with were there simply to check on the status of the General Electric contract. But the president of the court had a different interpretation: “When you come into an institution with a group of heavily armed men who have their faces covered and dressed in black, and whom we can’t even identify if they are police and they cross all of the perimeters to go into an area that is extremely sensitive where even some of the judges don’t go to, that is nothing more than an act of intimidation,” Rogavil Boisguéné told the Miami Herald. “It was a threat to prevent the court from doing its job.”

With the recent changes made by decree, the Haitian presidency will no longer have to wait for the court’s approval before moving forward with government contracts. In the decree, the Moïse administration argues that the reform is necessary due to the “unjustified slowness in the signing of contracts,” which, it argues, “is detrimental to the socio-economic development of the country.” A significant change is that the court’s opinions on draft contracts will only be “advisory” now. The court also will only have three to five days to issue an opinion before the government can move forward with the contract in question. Overall, the court’s review has been changed from ex-ante to ex-post; the court will still provide oversight, but only after the contract has been executed.

On November 12, the CSCCA’s president issued a brief statement taking note of the government’s decree. In the release, Boisguéné states that the court’s ex-ante control is derived from a “strict application” of the constitution and reminds public officials that “the administrative and financial responsibilities attached to their functions are strictly personal” and that is it “their responsibility” to “ensure that … opinions are respected within the framework of this constitutional provision.”

Haiti’s public finance system is notoriously cumbersome. In 2016, the World Bank noted that multiple institutions played similar roles in approving contracts, and that the CSCCA was conflicted in that it both approved contracts and then audited spending afterward. The National Commission on Public Procurement (CNMP) is also tasked with approving government contracts. “There is considerable debate within Haiti and among donors over the appropriateness and the utility of this ex-ante role [for the CSCCA]. However, it continues to date,” the Bank wrote. The new decree specifies that if the CNMP has approved of a contract, the CSCCA cannot prevent its execution regardless of if irregularities are identified.

But, shifting the CSCCA’s role without further efforts to ensure it is able to provide effective oversight on the back end sends a dangerous message, according to activists. The court would still be able to conduct audit reports such as those it produced on Petrocaribe, but the lack of judicial follow up to that report serves as an example of why limiting the court to after-the-fact auditing will be of limited value in preventing government waste or holding officials accountable.

With the president replacing the heads of the anticorruption and anti-money-laundering institutions in 2017, parliament now dissolved and the judiciary seemingly unable or unwilling to take on politically sensitive cases, the CSCCA had been one of the last remaining institutions able to check the powers of the presidency. In a country with a long track record of impunity, the changes have sounded alarm bells.

“Since 1986, we never had a head of state who had shown so much desire to neutralize the institutions of control,” economist Etzer Emile Tweeted. “This new decree could open the door for more acts of corruption in a country where impunity is king,” he added. Emile acknowledged that administrative procedures may be burdensome, but “it does not mean we have to remove the locks.” Checks and balances, he continued, “are critical … to guarantee transparency and good governance.”

On Sunday, a group of opposition political leaders issued a statement decrying the government’s desire to “to transform the country into a lawless state.” Moïse, the leaders argue, has repeatedly ignored constitutional limits on executive power, and they noted that ministers who sign these unconstitutional decrees could face legal repercussions after leaving office.

The president, in an interview Monday morning with Tele Métropole, was defiant. He repeated the argument that the reform was necessary to take on entrenched interests that simply wanted to block progress, and claimed that the decree would actually strengthen the CSCCA by allowing it to just focus on its auditing role. There is little doubt that Haiti’s procurement system needs to be reformed, but, in a comment to HRRW, a former high-ranking government official, who asked to remain anonymous, offered a different rationale for the changes: “To have the road completely opened to allow contracts without any restrictions to his friends or partners.”

On Friday, November 6, the Haitian government published in Le Moniteur a new decree limiting the powers of the Superior Court of Auditors and Administrative Disputes (CSCCA). The decree itself was signed by the president and ministers nearly two months earlier, on September 9, but was not formally made public until this past weekend. The court, one of only a handful of nominally independent government institutions, is responsible for reviewing draft government contracts as well as conducting audits. While its functions and title have been altered over time, the court was first established in 1823, and was only completely eliminated during the 19-year US occupation of Haiti. It was reestablished afterward and enshrined in the 1987 constitution.

President Moïse has ruled by decree, which is not formally allowed by the Haitian constitution, since January 2020, when the terms of most of parliament expired. He has extended executive powers, reforming the penal code, naming a new electoral council with a mandate to reform the constitution, and now weakening one of the last remaining institutions exercising government oversight. The latest decree follows years of conflict between the CSCCA and the Haitian presidency.

In 2018, anticorruption protesters began advocating for an investigation into Moïse and his predecessors’ handling of billions in Petrocaribe-related spending. Moïse, under increasing pressure from the streets, pledged to support such an investigation. The CSCCA has since released three audit reports on Petrocaribe, finding widespread irregularities and fraudulent practices in the management of the Venezuelan-led aid program, and directly implicating the president, and the company he led before his election. Last year, members of the court had to temporarily leave the country due to threats. As of yet, there has been no real judicial progress in holding anyone accountable for the misuse of public funds. The president has denied all the CSCCA’s allegations.

The conflict has extended beyond just the Petrocaribe investigation, however. In June, the court raised questions over a contract to provide the presidency with helicopters, which had gone to a close political ally. The same month, the CSCCA was accused of hampering the response to COVID when it identified irregularities in a number of contracts to provide the health ministry with face masks awarded under a state of emergency exception. The contracts, worth about $10 million, moved forward despite the concerns — which included companies that had no experience in the sector and one which was owned by the wife of a current minister in the government. The health emergency “served as a pretext … to accelerate the corruption machine,” according to The Center of Analysis and Research in Human Rights (CARDH). The organization found that $34 million in emergency spending had bypassed CSCCA review all together.

In late August, the court blocked a $57 million no-bid government contract with the US company, General Electric, and asked the government to make needed corrections. The president has held the deal up as a key to his pledge to provide electricity across the country. According to the court, one reason for the court’s delay in approving the GE contract was the presence of unknown subcontractors that were to be paid a portion of the total amount.

On September 6, Moïse held a “community dialogue” at the National Palace, where he declared that it would be necessary to “reform” the CSCCA. Public works minister Joacéus Nader went so far as to say the court was blocking progress in the country, and referred to its independent judges as “ignorant” and “incompetent.”

In response to comments made by Moïse, the court issued a five-page statement outlining a series of acts of intimidation and threats on its members. The court also provided some of the reasons why it had not approved contracts. “How is the Court responsible for the invalidity of this draft contract? Where are the blocking acts? Who is blocking whom, or who is blocking what?” the court asked.

Prime Minister Joseph Jouthe attempted to ease tensions, apologizing just days later on Nader’s behalf, and telling Haitian daily Le Nouvelliste that while it was possible to remove bottlenecks in contract processing, changes would not be made without the court’s involvement. We now know that by the time of Jouthe’s apology, the government had already drafted and signed the decree curtailing the court’s powers — but it had not yet been made public.

Two weeks after Jouthe’s apology, Nader appeared at the CSCCA’s offices in Petionville, claiming he and the large group he arrived with were there simply to check on the status of the General Electric contract. But the president of the court had a different interpretation: “When you come into an institution with a group of heavily armed men who have their faces covered and dressed in black, and whom we can’t even identify if they are police and they cross all of the perimeters to go into an area that is extremely sensitive where even some of the judges don’t go to, that is nothing more than an act of intimidation,” Rogavil Boisguéné told the Miami Herald. “It was a threat to prevent the court from doing its job.”

With the recent changes made by decree, the Haitian presidency will no longer have to wait for the court’s approval before moving forward with government contracts. In the decree, the Moïse administration argues that the reform is necessary due to the “unjustified slowness in the signing of contracts,” which, it argues, “is detrimental to the socio-economic development of the country.” A significant change is that the court’s opinions on draft contracts will only be “advisory” now. The court also will only have three to five days to issue an opinion before the government can move forward with the contract in question. Overall, the court’s review has been changed from ex-ante to ex-post; the court will still provide oversight, but only after the contract has been executed.

On November 12, the CSCCA’s president issued a brief statement taking note of the government’s decree. In the release, Boisguéné states that the court’s ex-ante control is derived from a “strict application” of the constitution and reminds public officials that “the administrative and financial responsibilities attached to their functions are strictly personal” and that is it “their responsibility” to “ensure that … opinions are respected within the framework of this constitutional provision.”

Haiti’s public finance system is notoriously cumbersome. In 2016, the World Bank noted that multiple institutions played similar roles in approving contracts, and that the CSCCA was conflicted in that it both approved contracts and then audited spending afterward. The National Commission on Public Procurement (CNMP) is also tasked with approving government contracts. “There is considerable debate within Haiti and among donors over the appropriateness and the utility of this ex-ante role [for the CSCCA]. However, it continues to date,” the Bank wrote. The new decree specifies that if the CNMP has approved of a contract, the CSCCA cannot prevent its execution regardless of if irregularities are identified.

But, shifting the CSCCA’s role without further efforts to ensure it is able to provide effective oversight on the back end sends a dangerous message, according to activists. The court would still be able to conduct audit reports such as those it produced on Petrocaribe, but the lack of judicial follow up to that report serves as an example of why limiting the court to after-the-fact auditing will be of limited value in preventing government waste or holding officials accountable.

With the president replacing the heads of the anticorruption and anti-money-laundering institutions in 2017, parliament now dissolved and the judiciary seemingly unable or unwilling to take on politically sensitive cases, the CSCCA had been one of the last remaining institutions able to check the powers of the presidency. In a country with a long track record of impunity, the changes have sounded alarm bells.

“Since 1986, we never had a head of state who had shown so much desire to neutralize the institutions of control,” economist Etzer Emile Tweeted. “This new decree could open the door for more acts of corruption in a country where impunity is king,” he added. Emile acknowledged that administrative procedures may be burdensome, but “it does not mean we have to remove the locks.” Checks and balances, he continued, “are critical … to guarantee transparency and good governance.”

On Sunday, a group of opposition political leaders issued a statement decrying the government’s desire to “to transform the country into a lawless state.” Moïse, the leaders argue, has repeatedly ignored constitutional limits on executive power, and they noted that ministers who sign these unconstitutional decrees could face legal repercussions after leaving office.

The president, in an interview Monday morning with Tele Métropole, was defiant. He repeated the argument that the reform was necessary to take on entrenched interests that simply wanted to block progress, and claimed that the decree would actually strengthen the CSCCA by allowing it to just focus on its auditing role. There is little doubt that Haiti’s procurement system needs to be reformed, but, in a comment to HRRW, a former high-ranking government official, who asked to remain anonymous, offered a different rationale for the changes: “To have the road completely opened to allow contracts without any restrictions to his friends or partners.”

• HaitiHaitiLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUnited StatesEE. UU.US Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.WorldEl Mundo

An Novanm 2019, nan kad sipò li pou PNH, Biwo Entènasyonal Dwòg ak Aplikasyon Lalwa nan Depatman Leta Ameriken bay bay lapolis yon kontra $73,000 pou pwovizyon “kit anti-manifestasyon” pou inite lapolis ki chaje kontwòl foul, CIMO, daprè enfòmasyon ki genyen nan baz done kontra gouvènman Ameriken.

Nan komansman ete a CIMO ak lot inite PNH te itilize gaz lakrimojèn ki fabrike Ozetazini pou yo dispèse aktivis ki te rasanble devan Ministè Lajistis e ki tap manifeste pou dwa a lavi pandan peyi a ap viv yon sitiyasyon prekòs. Lapolis fè zak represyon nan manifestasyon an aloske òganizate yo te resevwa lese pase nan men otorite legal yo avan yo manifeste. Sa se egzamp ki montre poukisa kontra Depatman leta sa yo enkyetan – pa selman poutet jan ekipman sa yo ap sèvi men poutèt òganizasyon ki resevwa kontra sa: X-International.

Daprè rekò entrepriz Florida yo, X-International apateni a Carl Frédéric Martin, alyas “Kappa”. Yon Ayisyen-Ameriken epi se yon ansyen manmb US Navy. Depi kèk lane, Martin enplike nan zafè fòs sekirite an Ayiti byen ke se koze bizness prive li ki pi enkyetan, patikilyèman kontra sa li genyen ak Depatman Leta.

An Jen, près lokal la repote ke Martin avec yon fanmi Dimitri Herard – ki se chèf gad Palè Nasyonal la – fome yon nouvo konpani, Haiti Ordnance Factory S.A (HOFSA). Daprè dokiman anrejistreman li, nouvo konpani sa ta otorize pou li fè zam ak aminisyon an Ayiti. Aprè nouvèl la gaye ke konpani sa te egziste, gouvènman Ayisyen an revoke lisans biznes li. Men sa se te selman youn nan nouvo biznis Dimitri Herard and Carl Frédéric Martin tapral fè.

An Avril 2020, avan koze HOFSA a te rive nan zorèy piblik la, Herard ak Martin te fòme yon lòt konpani: Tradex Haiti S.A. Kontrèman a HOFSA, Tradex pa otorize pou li fabrike zam ak aminisyon, li egziste tankou yon konpayi sekirite ki ka sèlman achte epi van ekipman sa yo. Herard ak Martin tap eseye rantre nan sektè zam lan pou plis pase yon lane. Kounya, daprè yon sous ki gen konesans sou endistri sa an Ayiti, yap opere youn nan dilèchip zam ki pi lucratif nan peyi a.

Arestasyon yon trafikan zam… yon opòtinite rate

Nan fen Desanm 2019, gouvènman Ayisyen an arete yon biznisman, Aby Larco. Akizasyon yo di li te yon sous enpotan nan zafè trafik zam nan peyi Dayiti. Larco te opere yon gwo konpayi zam pandan kek lane, konpayi sa te gen kontra ak Polis Nasyonal, Ambasad Ameriken te sèvi ak konpayi sa anpil pou reparasyon zam tou. Men, komisè ki aretel la di tou, li te enplike anpil nan koze vann zam pa anba, zam ki anpil fwa ta tonbe nan men gwoup kriminèl.

Aprè arestasyon Larco, komisyon dezameman, ki te kreye pou yo retire zam nan men sitwayen, deklare li gen yon lis kriminèl ki te resevwa zam nan men Larco. Plis pase 8 mwa pita, dosye Larco a pa avanse e pa gen nouvo enfòmasyon ki bay sou vant zam ilegal. Pandan tan sa a, arestasyon Larco a fè plas nan mache zam Ayiti pou lòt moun vinn enstale yo.

Daprè plizyè sous ki gen konesans sou dosye sa, Herard ak Martin te an diskisyon ak Larco pandan plizyè mwa pou yo gade si yo ka travay ansanm. A la fen, sous yo di Larco te rejete travay avèk yo. Sèt jou aprè yo finn aretel, anrejistreman HOSFA parèt nan Le Moniteur. Byen ke Prezidan Jovenel Moïse te vantel deske li te arete Larco e li te pale de sa kòm yon gwo viktwa nan koze batay kont trafik zam nan peyi a, gouvènman an pako di anyen sou chèf gad li kap travay tou antan ke yon dilè zam prive.

Herard li menm te enplike nan dosye abi dwa moun. Rapò Depatman Leta sou dwa moun an 2019 note ke Herard:

… tire e blese de(2) sitwayen nan zòn Delmas 15 nan Pòtoprens jou ki te 10 Jen. Aprè ensidan sa, plizye temwen swiv machin Herard lakay li nan Delmas 31. Lè li rive lakay li, Herard ak lòt polisye PNH ki te la kòmanse tire sou gwoup sitwayen yo e yo arive blese de (2) ladan yo.

Byen ke arestasyon Larco kreye plas pou Martin ak Herard rantre nan mache lokal sa, Martin ap travay nan sektè sa pandan byen lontan. Moun ki travay nan endistri sa konen Martin pou travay li konn fè nan asanble zam ak diferan pati- sa vle di manifaktire nouvo zam ki pa gen nimewo de seri, kidonk ke yo paka retrase. Anpil moun kwè ke se Martin ki te bay zam bay mèsenè Ameriken ki te arete an Ayiti an 2010 yo. Gen moun ki te wè li nan lari Potoprens mele ak lapolis pandan manifestasyon anti-gouvènmantal yo nan menm peryòd sa. Gen kèk douzèn manifestan ke yo te touye lè sa, daprè rapò òganizasyon dwa moun.

Etazini ap ogmante finansmanl malgre sitiyasyon dwa yo ap deteryore

An Jen, jou aprè la polis te kraze yon manifestasyon pasifik devan Ministè Lajistis, sitwayen òdinè ki te arme te desann anba lavil. Yo fè pati nouvo alyans: “G9 an Fanmi e Alye” ke ansyen polisye Jimmy Cherizier, dirije. Pesonn pat ka jwen lapolis lè sa a. Washington Post repote sou sa nan debi mwa sa a, li di:

Lè nèg Cherizier yo te pran lari an Jen, temwen di yo te wè yo kap sikile nan machinn Lapolis Nasyonal ak Machinn Fos Sekirite Espesyal. Ministè Lajistis Lucmane Delil denonse gang yo e li pase lòd bay lapolis pou yo swiv yo, apre kèk èdtan, Moïse revokel.

Kèk jou avan atik Washington Post lan, ni Anbasad Ameriken ak misyon Nasyon Zini an Ayiti a denonse proliferasyon ak pouvwa gwoup ame yo an Ayiti. Nasyon Zini espesyalman pale de Cherizier, sitou de enplikasyonl nan masak Gran Ravine an 2017, La Saline an 2019 ak tout lòt abi li fè depi lè a.

Òganizasyon dwa moun nan peyi a denonse fòmasyon G9 la e yo di ke alyans sa fè pati de plan gouvènman pou li konsolide kontwòl sou zòn nan peyi a ki plen moun avan eleksyon ki swadizan ap planifyen yo. Cherizier denye ke lap travay ak administrasyon Moïse la. Washington Post kontinye ekri:

Men pou konpatriyòt li ki soufri anpil, gwoup Cherizier a, G9, envoke anpil nan laterè Tonton Makout yo, ki te gwoup paramilitè ki terorize Ayiti pandan deseni anba diktaktè François “Papa Doc” Duvalier avek pitit li, Jean-Claude.

Pierre Esperance, Direktè RNDDH di “Gouvènman an pa di anyen a pwopo de [ekstansyon Cherizier a], e kominote entènasyonal la fè komsi yo pa wè.” “Pa gen eta de lwa anko, gang yo tounen makout. Sanble gen yon volonte pou yo enstale yon nouvo diktati.”

Reprezantant Amerikèn ki soti California, Maxine Waters, kondane Cherizier ak mank inisyativ gouvènman an, li pwente dwèt sou administrasyon Trump lan ak sipò li kontinye bay gouvènman Ayisyen an. Li di Washington Post “Pa gen vre preyokipasyon sou Ayisyen yo ak ka yo- ke prezidan an ap touyen yo oubyen bat yo […] toutotan nou gen prezidan an sou bò nou, tout bagay ok”

Michele Sison ki se yon ansyen Anbasadè Etazini an Ayiti di Post la konsa “olye pou nap lonje dwe sou moun […] bi nou se pou nou ankouraje tout aktè pou yo panse a sak pi sansib yo e kontinye fè fas a pi gwo difikilte yo”

Nan yo dènye rapò, RNDDH rapòte ke te gen omwen 111 moun ki te mouri anba zak vyolans gang nan Cité Soleil nan mwa Jen an Jiyè. Arestasyon Larco a an Desanm 2019 lan sanble pa afekte trafik zam na peyi a. Nan dènye semèn sa yo, temwen di yo wè moun kap pote gwo zam otomatik ki sanble travay Martin konn fè a. Sa a vle di ke gen yon posibilite ke zam li yo rive nan men gang ak gwoup vyolan, ke li vlel ou pa. Men menm lè akizasyon vyolasyon dwa moun -ak konplisite Lapolis- kontinye monte, Etazini kontinye ogmante sipò pal pou PNH.

Nan debi mwa sa, Depatman Leta di Kongrè a ke lap rebay $8 million nan bidjè ane denyè pou sipo PNH. Depi lè Trump prezidan, Etazini miltipliye sipò li pou PNH an 4. Li te kòmanse a $2.8 milyon an 2016 e ane dènyè li te rive $12.4 milyon. Avèk dènye realokasyon sa, chif ane sa a gen pou li pi wo. Sipò finansye ameriken yo bay PNH la reprezante plis pase 10% bidjè enstitisyon sa.

PNH, ki sot selebre 25 an degzistans, pa byen finanse e anpil nan anplwaye li yo pa menm resevwa yon salè regilye. Men nan anviwonman sa a, sipò Etazini ap bay la, pa sanble lap regle anyen espesyalman pa rapò a sitiyasyon sekirite a kap deteryore. Pou lapèn, sipò diplomatik ak finansye nan men administrasyon Trump la sanble ap soude rezo koripsyon yo ki ap antretni sitiyasyon ensekirite sa, sa ka gen konsekans motèl pou anpil moun.

Lajan Depatman Leta bay X-International selman reprezante yo ti mòso nan sipò finansye li bay PNH men malgre sa li represzante youn nan manyè sipò Ameriken an kontinye kenbe sitiyasyon peyi a janl ye a.

An Novanm 2019, nan kad sipò li pou PNH, Biwo Entènasyonal Dwòg ak Aplikasyon Lalwa nan Depatman Leta Ameriken bay bay lapolis yon kontra $73,000 pou pwovizyon “kit anti-manifestasyon” pou inite lapolis ki chaje kontwòl foul, CIMO, daprè enfòmasyon ki genyen nan baz done kontra gouvènman Ameriken.

Nan komansman ete a CIMO ak lot inite PNH te itilize gaz lakrimojèn ki fabrike Ozetazini pou yo dispèse aktivis ki te rasanble devan Ministè Lajistis e ki tap manifeste pou dwa a lavi pandan peyi a ap viv yon sitiyasyon prekòs. Lapolis fè zak represyon nan manifestasyon an aloske òganizate yo te resevwa lese pase nan men otorite legal yo avan yo manifeste. Sa se egzamp ki montre poukisa kontra Depatman leta sa yo enkyetan – pa selman poutet jan ekipman sa yo ap sèvi men poutèt òganizasyon ki resevwa kontra sa: X-International.

Daprè rekò entrepriz Florida yo, X-International apateni a Carl Frédéric Martin, alyas “Kappa”. Yon Ayisyen-Ameriken epi se yon ansyen manmb US Navy. Depi kèk lane, Martin enplike nan zafè fòs sekirite an Ayiti byen ke se koze bizness prive li ki pi enkyetan, patikilyèman kontra sa li genyen ak Depatman Leta.

An Jen, près lokal la repote ke Martin avec yon fanmi Dimitri Herard – ki se chèf gad Palè Nasyonal la – fome yon nouvo konpani, Haiti Ordnance Factory S.A (HOFSA). Daprè dokiman anrejistreman li, nouvo konpani sa ta otorize pou li fè zam ak aminisyon an Ayiti. Aprè nouvèl la gaye ke konpani sa te egziste, gouvènman Ayisyen an revoke lisans biznes li. Men sa se te selman youn nan nouvo biznis Dimitri Herard and Carl Frédéric Martin tapral fè.

An Avril 2020, avan koze HOFSA a te rive nan zorèy piblik la, Herard ak Martin te fòme yon lòt konpani: Tradex Haiti S.A. Kontrèman a HOFSA, Tradex pa otorize pou li fabrike zam ak aminisyon, li egziste tankou yon konpayi sekirite ki ka sèlman achte epi van ekipman sa yo. Herard ak Martin tap eseye rantre nan sektè zam lan pou plis pase yon lane. Kounya, daprè yon sous ki gen konesans sou endistri sa an Ayiti, yap opere youn nan dilèchip zam ki pi lucratif nan peyi a.

Arestasyon yon trafikan zam… yon opòtinite rate

Nan fen Desanm 2019, gouvènman Ayisyen an arete yon biznisman, Aby Larco. Akizasyon yo di li te yon sous enpotan nan zafè trafik zam nan peyi Dayiti. Larco te opere yon gwo konpayi zam pandan kek lane, konpayi sa te gen kontra ak Polis Nasyonal, Ambasad Ameriken te sèvi ak konpayi sa anpil pou reparasyon zam tou. Men, komisè ki aretel la di tou, li te enplike anpil nan koze vann zam pa anba, zam ki anpil fwa ta tonbe nan men gwoup kriminèl.

Aprè arestasyon Larco, komisyon dezameman, ki te kreye pou yo retire zam nan men sitwayen, deklare li gen yon lis kriminèl ki te resevwa zam nan men Larco. Plis pase 8 mwa pita, dosye Larco a pa avanse e pa gen nouvo enfòmasyon ki bay sou vant zam ilegal. Pandan tan sa a, arestasyon Larco a fè plas nan mache zam Ayiti pou lòt moun vinn enstale yo.

Daprè plizyè sous ki gen konesans sou dosye sa, Herard ak Martin te an diskisyon ak Larco pandan plizyè mwa pou yo gade si yo ka travay ansanm. A la fen, sous yo di Larco te rejete travay avèk yo. Sèt jou aprè yo finn aretel, anrejistreman HOSFA parèt nan Le Moniteur. Byen ke Prezidan Jovenel Moïse te vantel deske li te arete Larco e li te pale de sa kòm yon gwo viktwa nan koze batay kont trafik zam nan peyi a, gouvènman an pako di anyen sou chèf gad li kap travay tou antan ke yon dilè zam prive.

Herard li menm te enplike nan dosye abi dwa moun. Rapò Depatman Leta sou dwa moun an 2019 note ke Herard:

… tire e blese de(2) sitwayen nan zòn Delmas 15 nan Pòtoprens jou ki te 10 Jen. Aprè ensidan sa, plizye temwen swiv machin Herard lakay li nan Delmas 31. Lè li rive lakay li, Herard ak lòt polisye PNH ki te la kòmanse tire sou gwoup sitwayen yo e yo arive blese de (2) ladan yo.

Byen ke arestasyon Larco kreye plas pou Martin ak Herard rantre nan mache lokal sa, Martin ap travay nan sektè sa pandan byen lontan. Moun ki travay nan endistri sa konen Martin pou travay li konn fè nan asanble zam ak diferan pati- sa vle di manifaktire nouvo zam ki pa gen nimewo de seri, kidonk ke yo paka retrase. Anpil moun kwè ke se Martin ki te bay zam bay mèsenè Ameriken ki te arete an Ayiti an 2010 yo. Gen moun ki te wè li nan lari Potoprens mele ak lapolis pandan manifestasyon anti-gouvènmantal yo nan menm peryòd sa. Gen kèk douzèn manifestan ke yo te touye lè sa, daprè rapò òganizasyon dwa moun.

Etazini ap ogmante finansmanl malgre sitiyasyon dwa yo ap deteryore

An Jen, jou aprè la polis te kraze yon manifestasyon pasifik devan Ministè Lajistis, sitwayen òdinè ki te arme te desann anba lavil. Yo fè pati nouvo alyans: “G9 an Fanmi e Alye” ke ansyen polisye Jimmy Cherizier, dirije. Pesonn pat ka jwen lapolis lè sa a. Washington Post repote sou sa nan debi mwa sa a, li di:

Lè nèg Cherizier yo te pran lari an Jen, temwen di yo te wè yo kap sikile nan machinn Lapolis Nasyonal ak Machinn Fos Sekirite Espesyal. Ministè Lajistis Lucmane Delil denonse gang yo e li pase lòd bay lapolis pou yo swiv yo, apre kèk èdtan, Moïse revokel.

Kèk jou avan atik Washington Post lan, ni Anbasad Ameriken ak misyon Nasyon Zini an Ayiti a denonse proliferasyon ak pouvwa gwoup ame yo an Ayiti. Nasyon Zini espesyalman pale de Cherizier, sitou de enplikasyonl nan masak Gran Ravine an 2017, La Saline an 2019 ak tout lòt abi li fè depi lè a.

Òganizasyon dwa moun nan peyi a denonse fòmasyon G9 la e yo di ke alyans sa fè pati de plan gouvènman pou li konsolide kontwòl sou zòn nan peyi a ki plen moun avan eleksyon ki swadizan ap planifyen yo. Cherizier denye ke lap travay ak administrasyon Moïse la. Washington Post kontinye ekri:

Men pou konpatriyòt li ki soufri anpil, gwoup Cherizier a, G9, envoke anpil nan laterè Tonton Makout yo, ki te gwoup paramilitè ki terorize Ayiti pandan deseni anba diktaktè François “Papa Doc” Duvalier avek pitit li, Jean-Claude.

Pierre Esperance, Direktè RNDDH di “Gouvènman an pa di anyen a pwopo de [ekstansyon Cherizier a], e kominote entènasyonal la fè komsi yo pa wè.” “Pa gen eta de lwa anko, gang yo tounen makout. Sanble gen yon volonte pou yo enstale yon nouvo diktati.”

Reprezantant Amerikèn ki soti California, Maxine Waters, kondane Cherizier ak mank inisyativ gouvènman an, li pwente dwèt sou administrasyon Trump lan ak sipò li kontinye bay gouvènman Ayisyen an. Li di Washington Post “Pa gen vre preyokipasyon sou Ayisyen yo ak ka yo- ke prezidan an ap touyen yo oubyen bat yo […] toutotan nou gen prezidan an sou bò nou, tout bagay ok”

Michele Sison ki se yon ansyen Anbasadè Etazini an Ayiti di Post la konsa “olye pou nap lonje dwe sou moun […] bi nou se pou nou ankouraje tout aktè pou yo panse a sak pi sansib yo e kontinye fè fas a pi gwo difikilte yo”

Nan yo dènye rapò, RNDDH rapòte ke te gen omwen 111 moun ki te mouri anba zak vyolans gang nan Cité Soleil nan mwa Jen an Jiyè. Arestasyon Larco a an Desanm 2019 lan sanble pa afekte trafik zam na peyi a. Nan dènye semèn sa yo, temwen di yo wè moun kap pote gwo zam otomatik ki sanble travay Martin konn fè a. Sa a vle di ke gen yon posibilite ke zam li yo rive nan men gang ak gwoup vyolan, ke li vlel ou pa. Men menm lè akizasyon vyolasyon dwa moun -ak konplisite Lapolis- kontinye monte, Etazini kontinye ogmante sipò pal pou PNH.

Nan debi mwa sa, Depatman Leta di Kongrè a ke lap rebay $8 million nan bidjè ane denyè pou sipo PNH. Depi lè Trump prezidan, Etazini miltipliye sipò li pou PNH an 4. Li te kòmanse a $2.8 milyon an 2016 e ane dènyè li te rive $12.4 milyon. Avèk dènye realokasyon sa, chif ane sa a gen pou li pi wo. Sipò finansye ameriken yo bay PNH la reprezante plis pase 10% bidjè enstitisyon sa.

PNH, ki sot selebre 25 an degzistans, pa byen finanse e anpil nan anplwaye li yo pa menm resevwa yon salè regilye. Men nan anviwonman sa a, sipò Etazini ap bay la, pa sanble lap regle anyen espesyalman pa rapò a sitiyasyon sekirite a kap deteryore. Pou lapèn, sipò diplomatik ak finansye nan men administrasyon Trump la sanble ap soude rezo koripsyon yo ki ap antretni sitiyasyon ensekirite sa, sa ka gen konsekans motèl pou anpil moun.

Lajan Depatman Leta bay X-International selman reprezante yo ti mòso nan sipò finansye li bay PNH men malgre sa li represzante youn nan manyè sipò Ameriken an kontinye kenbe sitiyasyon peyi a janl ye a.

• HaitiHaitiLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

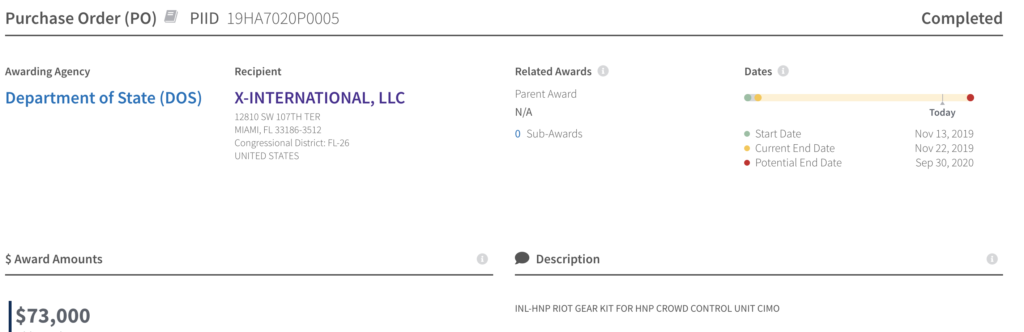

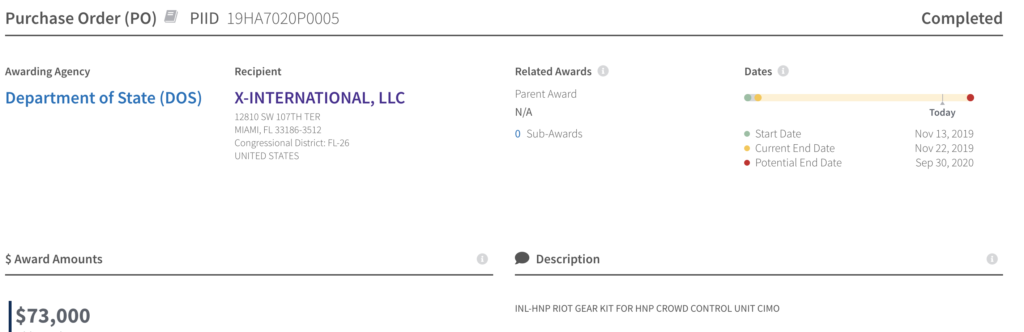

In November, 2019, as part of its support for the Haitian National Police (HNP), the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) awarded a $73,000 contract for the provision of “riot gear kit[s]” for the police’s crowd control unit, CIMO, according to information contained in the US government’s contracting database.

Earlier this summer, CIMO and other HNP units used US-manufactured tear gas to disperse activists who had assembled in front of the Ministry of Justice rallying for the right to life amid a rapidly deteriorating security situation. The police repressed the protest even though the organizers had received proper legal clearance. It was an example of why such State Department contracts are concerning — not just because of how the riot gear can be used on the ground, but because of the firm that received the contract: X-International.

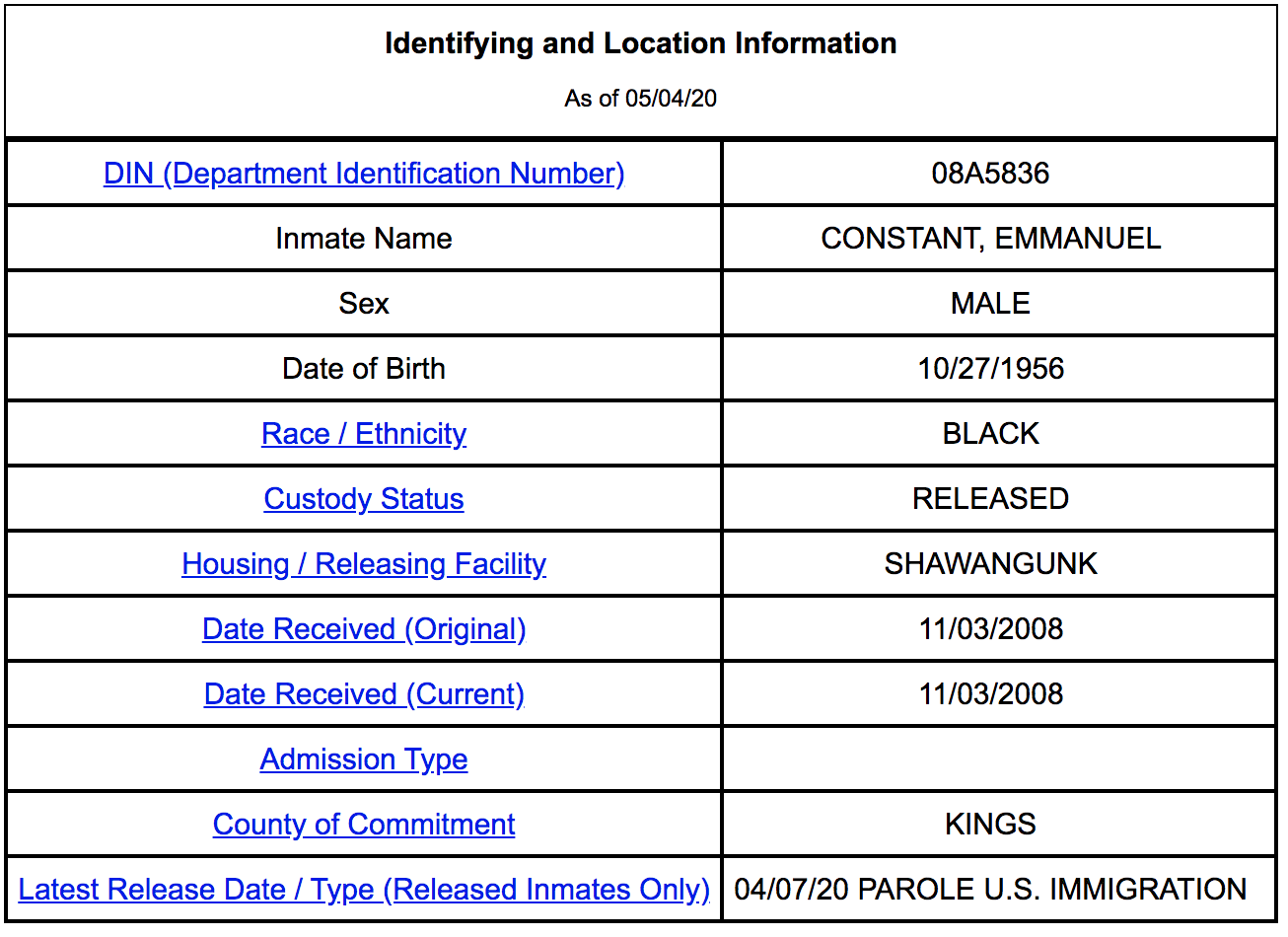

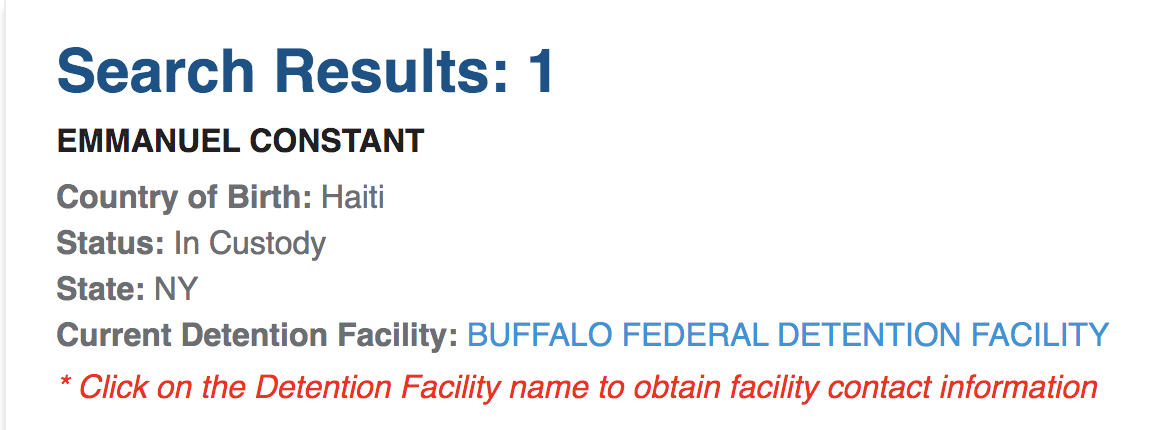

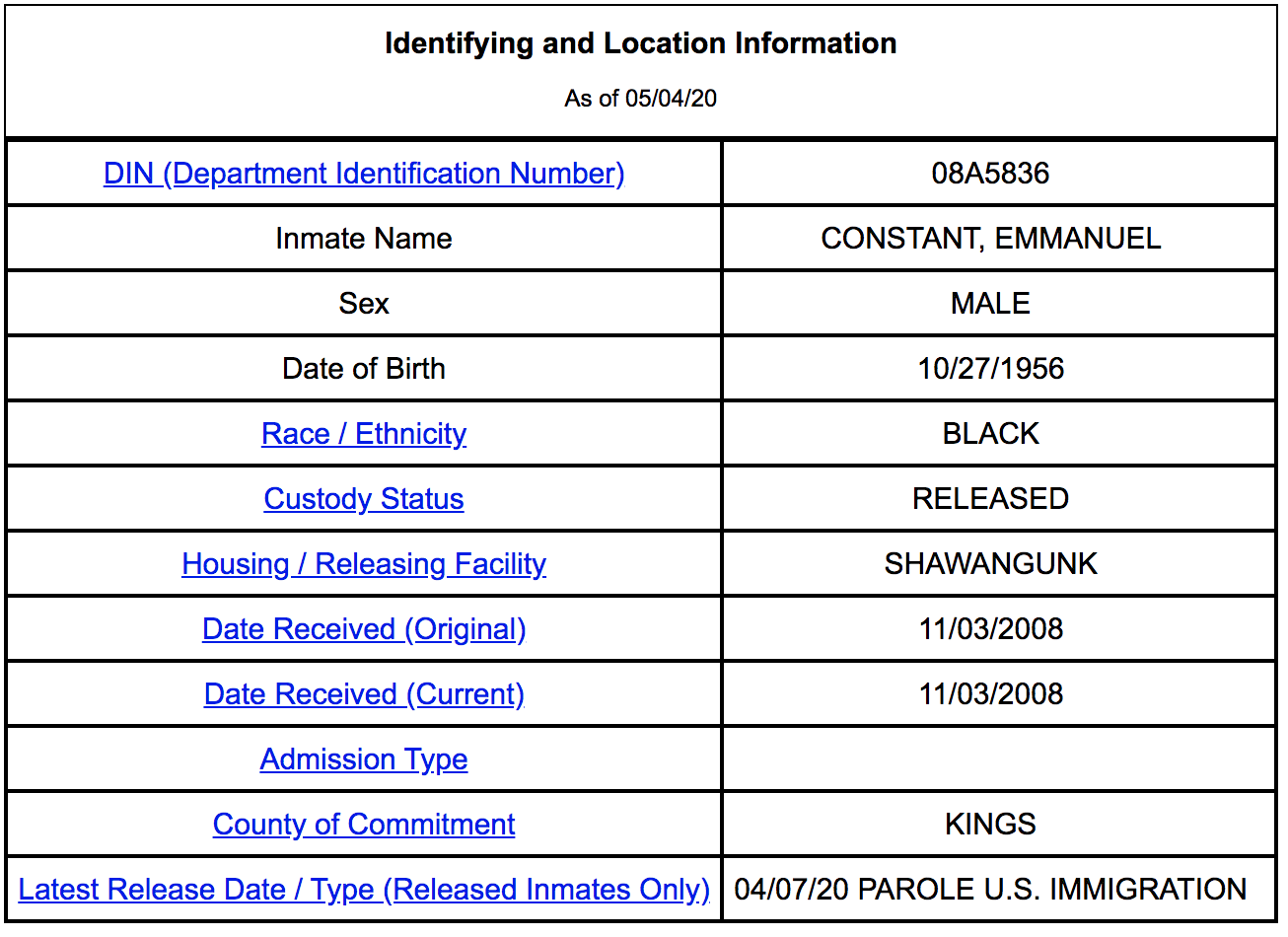

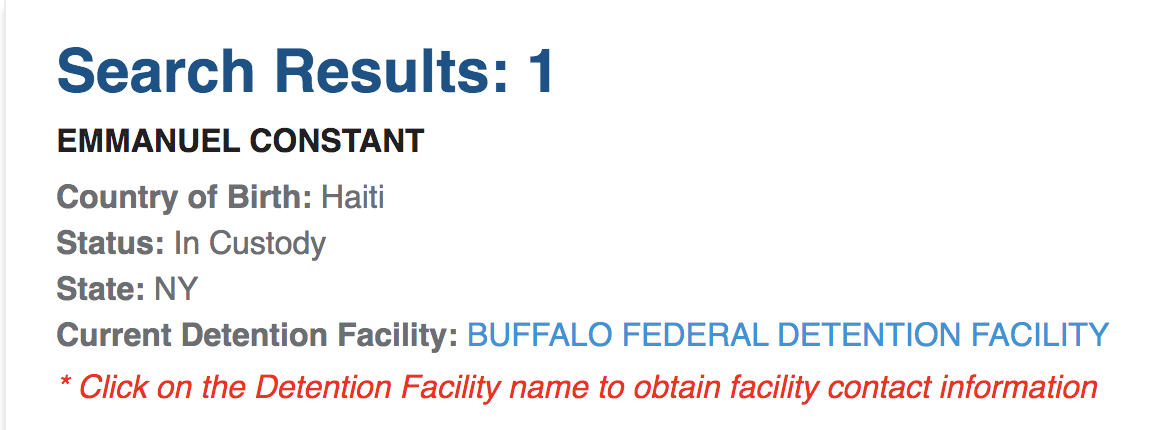

X-International, according to Florida corporate records, is owned by Carl Frédéric Martin, also known as “Kappa.” A Haitian-American and former member of the US Navy, Martin has become increasingly involved in Haiti’s security forces over the last few years, though, his private ventures should raise even more troubling questions about the State Department contract.

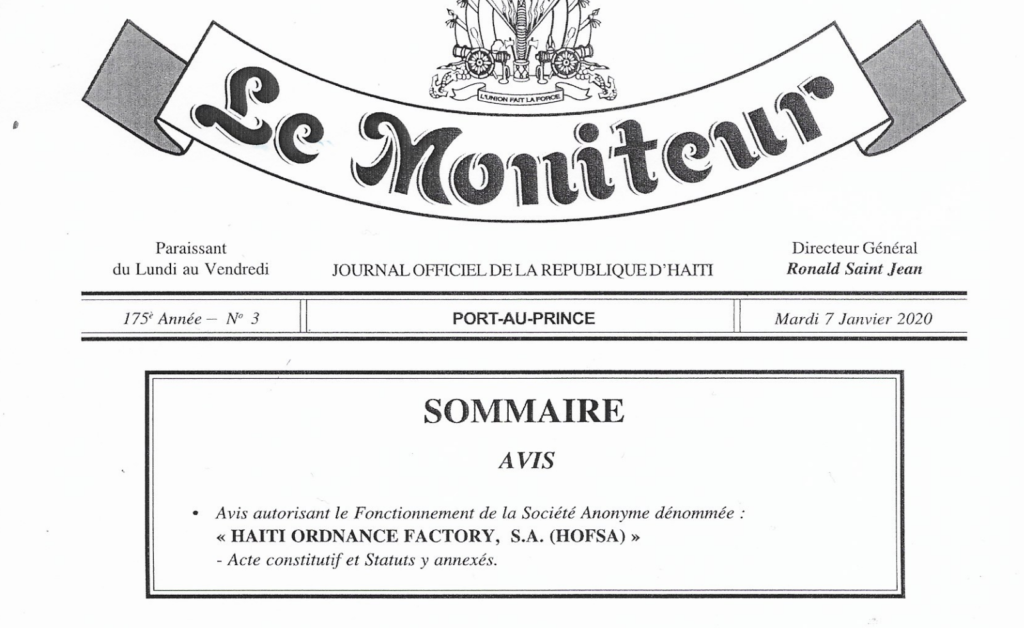

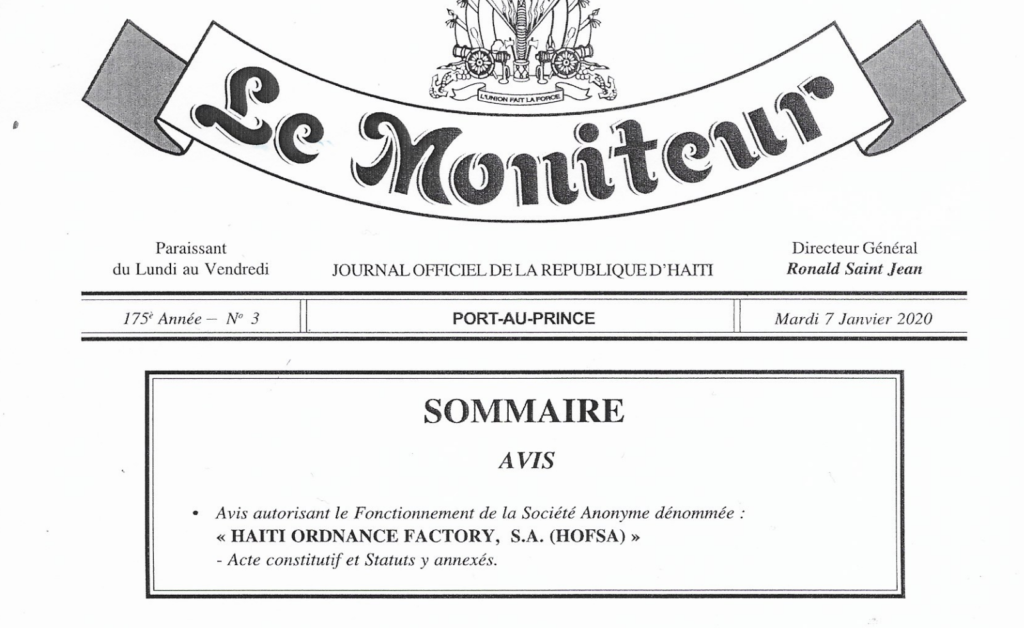

In June, local press reported that Martin, together with a relative of Dimitri Herard — the head of Haiti’s palace guard — had formed a new company, Haiti Ordnance Factory S.A. (HOFSA). According to its corporate registration documents, the new company would be authorized to manufacture weapons and ammunition in Haiti. After news of the company’s existence broke, however, the government revoked its business license. But this was just one of Herard and Martin’s new ventures.

In April 2020, before the controversy over HOFSA erupted in public, the two formed another company: Tradex Haiti S.A. Unlike HOFSA, Tradex is not authorized to manufacture weapons or ammunition, but is simply a security company that can buy and sell equipment. Herard and Martin had been trying to break into the arms market for more than a year. Now, according to a source with knowledge of the industry in Haiti, the two are operating one of the most lucrative arms dealerships in the country.

The arrest of an arms dealer … and an opportunity

In late December 2019, the Haitian government arrested businessman Aby Larco, accusing him of being a significant source of arms trafficking in Haiti. Larco had operated a well-known weapons company for years, with contracts with the HNP and also frequently used by the US embassy to repair firearms. But, prosecutors alleged, he was also an important supplier of black market weapons that wound up in the hands of criminal groups.

After Larco’s arrest, the government’s disarmament commission, created to help get weapons out of the hands of civilians, proclaimed it had a list of criminals who had received weapons from Larco. But more than eight months later, the case against Larco has stalled, and no information has been provided about possibly illegal weapon sales. Meanwhile, Larco’s arrest made space in the Haitian arms market for others to move in.

According to multiple sources close to the case, Herard and Martin had been in discussion with Larco for many months with an eye to possibly working together. In the end, however, the sources say Larco rejected their overtures. Seven days after his arrest, HOFSA’s corporate registration was published in Le Moniteur. Though President Jovenel Moïse touted Larco’s arrest as a blow against the proliferation of illegal weapons, the government has remained quiet about the head of the palace guard moonlighting as a private arms dealer.

Herard himself has been implicated in human rights abuses. The State Department’s own 2019 human rights report notes that Herard:

… shot and wounded two civilians in the Delmas 15 area of Port-au-Prince on June 10. Following this incident, several witnesses pursued Herard’s vehicle toward his residence in Delmas 31. Upon arriving at the residence, Herard and other HNP officers on the scene opened fire on the group of civilians, resulting in two others being wounded.

Though Larco’s arrest may have created space for Martin and Herard to enter the local market, Martin has been an arms dealer for much longer. Among those with knowledge of the local arms market, Martin is known for assembling weapons from disparate parts — in other words, manufacturing weapons that lack serial numbers and cannot be tracked. Some believe it was Martin who provided weapons to US mercenaries arrested in Haiti in 2019. Martin was seen on the streets of the capital embedded with the police during the height of anti-government protests around the same time period. Dozens of protesters were killed, according to local human rights organizations.

US increasing police funding despite worsening rights situation

In June, the day after police broke up the peaceful demonstration in front of the ministry of justice, armed civilians rallied in downtown Port-au-Prince. They were part of a new alliance: the “G9 Family and Allies,” led by a former police officer, Jimmy Cherizier. The police were nowhere to be found, however. The Washington Post reported earlier this month:

When Cherizier’s men took to the streets in June, witnesses claimed to have seen them ride in the same armored vehicles used by the national police and special security forces. Justice Minister Lucmane Delile denounced the gangs and ordered the national police to pursue them; within hours, Moïse fired him.

In the days before the Post article, both the US Embassy and the United Nations mission in Haiti denounced the proliferation and power of armed groups in Haiti. The UN specifically mentioned Cherizier, noting his alleged role in the massacres at Grand Ravine in 2017 and La Saline in 2018, and myriad other abuses since.

Local rights organizations have also denounced the formation of the G9, and have alleged that the alliance is part of a government plan to consolidate control in the densely populated capital ahead of yet-to-be-scheduled elections. Cherizier has denied he is working with the Moïse administration. The Post continued:

But for his long-suffering countrymen, Cherizier’s G9 is evoking the horrors of the Tontons Macoutes, the government-backed paramilitaries that terrorized Haiti for decades under dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude.

“The government has said nothing about [Cherizier’s rise], and the international community has turned a blind eye,” said Pierre Espérance, director of Haiti’s National Human Rights Defense Network. “There is no rule of law anymore. The gangs are the new Macoutes. It feels like there is a manifest will to install a new dictatorship.”

US Congresswoman Maxine Waters (D-CA) has condemned Cherizier and the government’s inaction, pointing the finger at the Trump administration’s unconditional support for the Haitian government. “There is no real concern for the plight of the Haitians, whether they are being beaten and killed by the president of Haiti,” she told The Post. “As long as the president is in our pockets, everything is okay.”

Michele Sison, the US ambassador to Haiti, pushed back. “Rather than pointing fingers,” she told The Post, “our point is to encourage all actors . . . to think about the most vulnerable who continue to bear the brunt of these challenges.”

In a recent report, the National Human Rights Defense Network reported that at least 111 civilians had been killed in gang violence in Cité Soleil in June and July. The December 2019 arrest of Larco, meanwhile, has done little to stem the illegal flow of weapons. In recent weeks, witnesses have seen armed civilians in Cité Soleil carrying automatic weapons that appear to bear the trademark of Carl Martin’s handiwork, raising the possibility that, willingly or not, his guns may be making their way into the hands of civilians. But even as allegations of rights abuses — and police complicity — pile up, the US has deepened its support for the HNP.

Earlier this month, the State Department notified Congress that it was reallocating $8 million from last year’s budget to support the HNP. Since Trump took office, the US has nearly quadrupled its support to Haiti’s police — from $2.8 million in 2016 to more than $12.4 million last year. With the recent reallocation, the figure this year will likely be even higher. US funding for the Haitian police constitutes more than 10 percent of the institution’s overall budget.

The HNP, which recently celebrated its 25th anniversary, has been chronically underfunded, and many officers do not even receive regular paychecks. But, in the current environment, ramped up US support for the police is unlikely to improve the rapidly devolving security situation. Rather, continued diplomatic and financial support from the Trump administration is likely to only harden the corrupt networks that perpetuate insecurity — with potentially deadly political consequences. The State Department award to X-International makes up only a small portion of overall US support to the police, but nevertheless, it is emblematic of the various ways US assistance empowers Haiti’s status quo.

In November, 2019, as part of its support for the Haitian National Police (HNP), the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) awarded a $73,000 contract for the provision of “riot gear kit[s]” for the police’s crowd control unit, CIMO, according to information contained in the US government’s contracting database.

Earlier this summer, CIMO and other HNP units used US-manufactured tear gas to disperse activists who had assembled in front of the Ministry of Justice rallying for the right to life amid a rapidly deteriorating security situation. The police repressed the protest even though the organizers had received proper legal clearance. It was an example of why such State Department contracts are concerning — not just because of how the riot gear can be used on the ground, but because of the firm that received the contract: X-International.

X-International, according to Florida corporate records, is owned by Carl Frédéric Martin, also known as “Kappa.” A Haitian-American and former member of the US Navy, Martin has become increasingly involved in Haiti’s security forces over the last few years, though, his private ventures should raise even more troubling questions about the State Department contract.

In June, local press reported that Martin, together with a relative of Dimitri Herard — the head of Haiti’s palace guard — had formed a new company, Haiti Ordnance Factory S.A. (HOFSA). According to its corporate registration documents, the new company would be authorized to manufacture weapons and ammunition in Haiti. After news of the company’s existence broke, however, the government revoked its business license. But this was just one of Herard and Martin’s new ventures.

In April 2020, before the controversy over HOFSA erupted in public, the two formed another company: Tradex Haiti S.A. Unlike HOFSA, Tradex is not authorized to manufacture weapons or ammunition, but is simply a security company that can buy and sell equipment. Herard and Martin had been trying to break into the arms market for more than a year. Now, according to a source with knowledge of the industry in Haiti, the two are operating one of the most lucrative arms dealerships in the country.

The arrest of an arms dealer … and an opportunity

In late December 2019, the Haitian government arrested businessman Aby Larco, accusing him of being a significant source of arms trafficking in Haiti. Larco had operated a well-known weapons company for years, with contracts with the HNP and also frequently used by the US embassy to repair firearms. But, prosecutors alleged, he was also an important supplier of black market weapons that wound up in the hands of criminal groups.

After Larco’s arrest, the government’s disarmament commission, created to help get weapons out of the hands of civilians, proclaimed it had a list of criminals who had received weapons from Larco. But more than eight months later, the case against Larco has stalled, and no information has been provided about possibly illegal weapon sales. Meanwhile, Larco’s arrest made space in the Haitian arms market for others to move in.

According to multiple sources close to the case, Herard and Martin had been in discussion with Larco for many months with an eye to possibly working together. In the end, however, the sources say Larco rejected their overtures. Seven days after his arrest, HOFSA’s corporate registration was published in Le Moniteur. Though President Jovenel Moïse touted Larco’s arrest as a blow against the proliferation of illegal weapons, the government has remained quiet about the head of the palace guard moonlighting as a private arms dealer.

Herard himself has been implicated in human rights abuses. The State Department’s own 2019 human rights report notes that Herard:

… shot and wounded two civilians in the Delmas 15 area of Port-au-Prince on June 10. Following this incident, several witnesses pursued Herard’s vehicle toward his residence in Delmas 31. Upon arriving at the residence, Herard and other HNP officers on the scene opened fire on the group of civilians, resulting in two others being wounded.

Though Larco’s arrest may have created space for Martin and Herard to enter the local market, Martin has been an arms dealer for much longer. Among those with knowledge of the local arms market, Martin is known for assembling weapons from disparate parts — in other words, manufacturing weapons that lack serial numbers and cannot be tracked. Some believe it was Martin who provided weapons to US mercenaries arrested in Haiti in 2019. Martin was seen on the streets of the capital embedded with the police during the height of anti-government protests around the same time period. Dozens of protesters were killed, according to local human rights organizations.

US increasing police funding despite worsening rights situation

In June, the day after police broke up the peaceful demonstration in front of the ministry of justice, armed civilians rallied in downtown Port-au-Prince. They were part of a new alliance: the “G9 Family and Allies,” led by a former police officer, Jimmy Cherizier. The police were nowhere to be found, however. The Washington Post reported earlier this month:

When Cherizier’s men took to the streets in June, witnesses claimed to have seen them ride in the same armored vehicles used by the national police and special security forces. Justice Minister Lucmane Delile denounced the gangs and ordered the national police to pursue them; within hours, Moïse fired him.

In the days before the Post article, both the US Embassy and the United Nations mission in Haiti denounced the proliferation and power of armed groups in Haiti. The UN specifically mentioned Cherizier, noting his alleged role in the massacres at Grand Ravine in 2017 and La Saline in 2018, and myriad other abuses since.

Local rights organizations have also denounced the formation of the G9, and have alleged that the alliance is part of a government plan to consolidate control in the densely populated capital ahead of yet-to-be-scheduled elections. Cherizier has denied he is working with the Moïse administration. The Post continued:

But for his long-suffering countrymen, Cherizier’s G9 is evoking the horrors of the Tontons Macoutes, the government-backed paramilitaries that terrorized Haiti for decades under dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude.

“The government has said nothing about [Cherizier’s rise], and the international community has turned a blind eye,” said Pierre Espérance, director of Haiti’s National Human Rights Defense Network. “There is no rule of law anymore. The gangs are the new Macoutes. It feels like there is a manifest will to install a new dictatorship.”

US Congresswoman Maxine Waters (D-CA) has condemned Cherizier and the government’s inaction, pointing the finger at the Trump administration’s unconditional support for the Haitian government. “There is no real concern for the plight of the Haitians, whether they are being beaten and killed by the president of Haiti,” she told The Post. “As long as the president is in our pockets, everything is okay.”

Michele Sison, the US ambassador to Haiti, pushed back. “Rather than pointing fingers,” she told The Post, “our point is to encourage all actors . . . to think about the most vulnerable who continue to bear the brunt of these challenges.”

In a recent report, the National Human Rights Defense Network reported that at least 111 civilians had been killed in gang violence in Cité Soleil in June and July. The December 2019 arrest of Larco, meanwhile, has done little to stem the illegal flow of weapons. In recent weeks, witnesses have seen armed civilians in Cité Soleil carrying automatic weapons that appear to bear the trademark of Carl Martin’s handiwork, raising the possibility that, willingly or not, his guns may be making their way into the hands of civilians. But even as allegations of rights abuses — and police complicity — pile up, the US has deepened its support for the HNP.

Earlier this month, the State Department notified Congress that it was reallocating $8 million from last year’s budget to support the HNP. Since Trump took office, the US has nearly quadrupled its support to Haiti’s police — from $2.8 million in 2016 to more than $12.4 million last year. With the recent reallocation, the figure this year will likely be even higher. US funding for the Haitian police constitutes more than 10 percent of the institution’s overall budget.

The HNP, which recently celebrated its 25th anniversary, has been chronically underfunded, and many officers do not even receive regular paychecks. But, in the current environment, ramped up US support for the police is unlikely to improve the rapidly devolving security situation. Rather, continued diplomatic and financial support from the Trump administration is likely to only harden the corrupt networks that perpetuate insecurity — with potentially deadly political consequences. The State Department award to X-International makes up only a small portion of overall US support to the police, but nevertheless, it is emblematic of the various ways US assistance empowers Haiti’s status quo.

• HaitiHaitiLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

Haitian president Jovenel Moïse, governing without parliament after terms expired in January without new elections taking place, is facing increasing questions over when, exactly, his own presidential mandate ends. Moïse assumed the presidency after 2015 presidential elections, which had to be rerun after the discovery of widespread irregularities that undermined the credibility of the vote. That fraught electoral process delayed Moïse’s inauguration by a year; now the question has become if that year counts toward the president’s five-year mandate.

On Friday, May 29, the office of Organization of American States (OAS) Secretary General Luis Almagro issued a press release taking a stand on the question of Moïse’s mandate, saying:

The OAS General Secretariat urges all political forces in Haiti to find a cooperative framework in order to comply with the letter and the spirit of their constitutional order, respecting the five-year presidential term in office. In this context, the term of President Jovenel Moïse ends on February 7, 2022.

Amid a domestic political crisis, the OAS’ comments amount to an intervention in the affairs of a member country, which goes against the institution’s own charter. “The Organization of American States has no powers other than those expressly conferred upon it by this Charter, none of whose provisions authorizes it to intervene in matters that are within the internal jurisdiction of the Member States,” Article I of the charter reads. It would be difficult to argue that issues of constitutional interpretation are anything other than the “internal jurisdiction of member states.”

The OAS press release follows an open letter to Almagro from Edmonde Supplice Beauzile, the head of Fusion of Haitian Social Democrats, a centrist Haitian political party. After outlining a history of perceived antidemocratic abuses on the part on the Moïse administration, Beauzile noted that Moïse “is engaged in an all-out campaign” to extend his term to 2022 and expressed her “hope that the regional organization which has distinguished itself in the recent past by applying its seal of approval on at least questionable elections, will not agree to support an apprentice dictator who has demonstrated the little respect he has for the constitution, the rule of law and democracy.”

On June 2, seven Haitian human rights organizations sent a letter to Almagro, condemning his remarks as contrary to the OAS charter and detailing their legal interpretation of the presidential mandate. “President Moïse cannot determine the duration of his term of office, in the same way that the Secretary General himself could not define his own mandate according to his interpretation of the OAS Charter,” the organizations wrote.

“There is no doubt,” the groups write, “that the mandate of President Jovenel Moïse ends on February 7, 2021.”

Questions over Moïse’s mandate stem from the 2015/2016 electoral process, but the OAS’ role in that process, and its previous intervention in the 2010 election, is now undermining the institution’s ability to play a helpful role in the current political crisis.

On election day in 2010, the Core Group in Haiti — which includes the OAS — attempted to force then president René Préval into accepting a plane to take him into exile. The election was marred by significant irregularities — including that more than 10 percent of the vote was never counted. Nevertheless, the OAS initially backed the legitimacy of the vote. Eventually, however, the OAS sent an “expert mission” to analyze the poll returns after Préval’s chosen successor appeared headed to a runoff. The OAS mission, without performing a full recount or even conducting a statistical analysis of the missing votes, recommended overturning the results of the election and placing the third-place finisher, Michel Martelly, into the runoff election at the expense of Préval’s successor.

The brazen intervention, backed up by threats of aid cutoffs and visa sanctions, has inextricably tied the fate of the OAS in Haiti with Martelly and his political party, Parti Haïtien Tèt Kale (PHTK). The 2015/2016 electoral process did little to dispel those concerns.

The 2015 elections were the first elections held under the Martelly administration — and, similar to today’s situation, only took place after the terms of parliament expired and Martelly was ruling by decree. (The Haitian constitution does not actually allow presidents to rule-by-decree.) The OAS provided funding and technical support for the election, and then sent an observer mission to monitor the vote.

Despite reports from local observer groups that the election had been marred by widespread irregularities, the OAS observer mission provided the results with its stamp of approval. Opposition parties pledged to boycott the runoff vote, and, under increasing pressure from street protests, the electoral council postponed the election. The OAS eventually acquiesced to Haitian demands for an audit of the vote, and even sent a special mission to negotiate the end of Martelly’s mandate in early 2016 — which paved the way for a transitional government, an audit of the vote, and a do-over election in November 2016. Notably, the rerun election was held under the same electoral law and without reopening candidate registrations.

The negotiated end of Martelly’s mandate actually provides a precedenct in the current crisis, the seven human rights organizations argue. The beginning of Martelly’s mandate was delayed a number of months by the 2010 electoral fracas, nevertheless, Martelly left office on February 7, 2016 — months before he hit five years. (Notably, former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide was not allowed to serve his full first term after returning to the presidency in 1994. This followed the 1991 coup d’etat that saw Aristide deposed and exiled for a total of three years.)

In their letter to Almagro, the seven organizations point out that Martelly himself acknowledged this in his parting speech. “[M]y mandate is nearing its end,” Martelly said at the time. “According to Article 134-1 of the Mother Law, the presidential term is five (5) years. This period begins and ends on February 7 of the fifth year of the mandate, regardless of the start date.”

The key question facing Haiti now is: when did the constitutional mandate of the president actually begin? The Moïse administration has argued the constitution is clear — and confers a president with a five-year mandate. If Moïse took office in February 2017, his term should therefore conclude in February 2022. The rights organizations, however, contend that Moïse should not be able to benefit from the fraud-pocked election which had to be reheld. The constitution, they argue, is clear that the presidential mandate begins following the election — meaning that, constitutionally, the mandate began in February 2016, following the October 2015 vote, and will end in 2021, regardless of when the president himself took office.

The rights organizations also point to the 2015 electoral law, which notes that, if the election is not held in the constitutional timetable, “The term of office of the President of the Republic shall end on the seventh (7th) of February in the fifth year of his term of office, regardless of the date of his entry into office.”

Further, the organizations point to the recent expiration of parliaments’ terms as an additional precedent. On January 13, in a tweet, President Moïse declared the terms of parliament complete. However, as the organizations note, some deputies and senators had not completed their full mandate. “As the legislature ended on the second Monday of January 2020, all Congressman, regardless of the year in which they took office, left Parliament.”

The focus on a constitutional interpretation, however, obscures a deeper issue. No election has been held under the Moïse administration, no elections are scheduled, and there is no functioning parliament to serve as a check on the presidency.

Last week, the Haitian government requested support from the OAS in organizing elections this year, but opposition politicians — emboldened by nearly two years of popular frustration and protests against the Moïse administration and government corruption — have shown little willingness to participate in elections organized by the current government.

For much of the past two years, the donor community, including the OAS, has advocated for dialogue — a political negotiation to reach agreement around elections, mandates, and governance. Regardless of when exactly the president’s term ends, it has become clear that the only way forward will be through a broad, consensual, and Haitian-led political accord. Allowing Moïse to stay in office until 2022 without addressing the other, related, political issues such as elections, will only serve to kick the can down the road. The statement from the OAS Secretary General won’t help in the slightest, and will only further prove to Haiti’s opposition that the OAS is serving as an overt political actor in Haiti as opposed to a neutral arbiter.

The relationship between President Moïse and the OAS and Secretary General Almagro has deepened in recent years. In January 2019, Haiti sided with the United States and voted at the OAS to condemn the Maduro government in Venezuela and recognize the Juan Guaidó “administration.” In doing so, Haiti broke from the majority of CARICOM countries, which have long voted as a bloc — especially in matters of concern to national sovereignty.

Moïse, at the time, was facing his own internal political crisis over his role in the Petrocaribe corruption scandal; his government’s acquiescence to the interests of Washington and Almagro proved useful in ensuring his own political survival. In the fall of 2018, #KoteKobPetrokaribeA? (where is the Petrocaribe money?) began trending on social media, and in the streets of Haiti. The protest movement was given new impetus in the spring of 2019 when government auditors released a lengthy investigation into Petrocaribe, revealing that multiple companies owned by President Moïse had received government money for work that was never completed.

In June, Carlos Trujillo, the US ambassador to the OAS, led a “fact-finding” delegation to Haiti. An anonymous official on the trip told the Miami Herald that the OAS was prepared to assist in the PetroCaribe scandal and help determine who should face prosecution. Moïse, the official continued, “said he was ready to go to Washington and sign. He said he has nothing to hide.”

“This shows a willingness by the OAS to impose a solution without listening to the popular demands of the population,” Nou Pap Domi, an anticorruption collective, said in response. “[But] we at Nou Pap Domi are committed to finding a solution to Haiti with Haitians.”

“The presence of the OAS does not change our position,” the collective added. “But we wrote the OAS on June 8, 2019, to inform them that we do not recognize the legitimacy of President Jovenel Moïse and we have no trust in him leading the country because he has serious allegations that involve corruption.”

Moïse, facing calls for his resignation, continued to point to the OAS’ work. In July, he wrote in a Miami Herald opinion piece that he was “working with the [OAS] to assemble a team of independent international financial experts for a commission that will work around our broken politics to deliver a fair, credible, objective audit so that Haitian judges can pursue accountability for anyone found to have committed crimes and stolen from the Haitian people.”

But, while the OAS has since begun raising funds for an anticorruption program in Haiti, it was never meant to investigate Petrocaribe. It was later revealed by Antigua and Barbuda’s ambassador to the OAS, Sir Ronald Sanders (who led the OAS team that negotiated Martelly’s exit from office), that Trujillo’s “fact-finding” mission was not actually on behalf of the entire organization, but just on his own behalf as acting president of the OAS Permanent Council. Progress on the Petrocaribe dossier has stalled, and Moïse has remained in office.

While the OAS has now offered its own constitutional interpretation of Moïse’s mandate, it remained alarmingly silent when the terms of parliament expired in January 2020. In fact, Almagro personally traveled to Haiti on January 7, just days before. The expiration of parliament’s terms represented a possible break in Haiti’s democratic order, and there was concern that some countries could push the OAS to invoke the democratic charter against the Moïse administration (as Moïse had helped the OAS do to Venezuela the year prior).

Almagro, however, was in the midst of his own political fight — competing for reelection as secretary general and looking to ensure support throughout the region. The two leaders needed one another. If the quid pro quo wasn’t explicit during the two leader’s conversations, Almagro’s public comments spoke for themselves.

“Today I reiterated to President @Moïsejovenel our staunch support for good governance & political stability in #Haiti, which includes reaching a political agreement, promoting constant and inclusive dialogue,” the Secretary General tweeted. He made no reference to the fact that the president would be in office without a functioning parliament in just five days’ time.

Over the previous decade, OAS leadership has tied itself to successive PHTK governments in Haiti. As the Haitian government once again calls in OAS support, few Haitians will forget the manner in which that relationship was forged, nor are they likely to see the OAS as an institution capable of facilitating an exit to the current political crisis — which in many ways stems from the OAS intervention ten years ago.

Haitian president Jovenel Moïse, governing without parliament after terms expired in January without new elections taking place, is facing increasing questions over when, exactly, his own presidential mandate ends. Moïse assumed the presidency after 2015 presidential elections, which had to be rerun after the discovery of widespread irregularities that undermined the credibility of the vote. That fraught electoral process delayed Moïse’s inauguration by a year; now the question has become if that year counts toward the president’s five-year mandate.

On Friday, May 29, the office of Organization of American States (OAS) Secretary General Luis Almagro issued a press release taking a stand on the question of Moïse’s mandate, saying:

The OAS General Secretariat urges all political forces in Haiti to find a cooperative framework in order to comply with the letter and the spirit of their constitutional order, respecting the five-year presidential term in office. In this context, the term of President Jovenel Moïse ends on February 7, 2022.

Amid a domestic political crisis, the OAS’ comments amount to an intervention in the affairs of a member country, which goes against the institution’s own charter. “The Organization of American States has no powers other than those expressly conferred upon it by this Charter, none of whose provisions authorizes it to intervene in matters that are within the internal jurisdiction of the Member States,” Article I of the charter reads. It would be difficult to argue that issues of constitutional interpretation are anything other than the “internal jurisdiction of member states.”

The OAS press release follows an open letter to Almagro from Edmonde Supplice Beauzile, the head of Fusion of Haitian Social Democrats, a centrist Haitian political party. After outlining a history of perceived antidemocratic abuses on the part on the Moïse administration, Beauzile noted that Moïse “is engaged in an all-out campaign” to extend his term to 2022 and expressed her “hope that the regional organization which has distinguished itself in the recent past by applying its seal of approval on at least questionable elections, will not agree to support an apprentice dictator who has demonstrated the little respect he has for the constitution, the rule of law and democracy.”

On June 2, seven Haitian human rights organizations sent a letter to Almagro, condemning his remarks as contrary to the OAS charter and detailing their legal interpretation of the presidential mandate. “President Moïse cannot determine the duration of his term of office, in the same way that the Secretary General himself could not define his own mandate according to his interpretation of the OAS Charter,” the organizations wrote.

“There is no doubt,” the groups write, “that the mandate of President Jovenel Moïse ends on February 7, 2021.”

Questions over Moïse’s mandate stem from the 2015/2016 electoral process, but the OAS’ role in that process, and its previous intervention in the 2010 election, is now undermining the institution’s ability to play a helpful role in the current political crisis.

On election day in 2010, the Core Group in Haiti — which includes the OAS — attempted to force then president René Préval into accepting a plane to take him into exile. The election was marred by significant irregularities — including that more than 10 percent of the vote was never counted. Nevertheless, the OAS initially backed the legitimacy of the vote. Eventually, however, the OAS sent an “expert mission” to analyze the poll returns after Préval’s chosen successor appeared headed to a runoff. The OAS mission, without performing a full recount or even conducting a statistical analysis of the missing votes, recommended overturning the results of the election and placing the third-place finisher, Michel Martelly, into the runoff election at the expense of Préval’s successor.

The brazen intervention, backed up by threats of aid cutoffs and visa sanctions, has inextricably tied the fate of the OAS in Haiti with Martelly and his political party, Parti Haïtien Tèt Kale (PHTK). The 2015/2016 electoral process did little to dispel those concerns.

The 2015 elections were the first elections held under the Martelly administration — and, similar to today’s situation, only took place after the terms of parliament expired and Martelly was ruling by decree. (The Haitian constitution does not actually allow presidents to rule-by-decree.) The OAS provided funding and technical support for the election, and then sent an observer mission to monitor the vote.

Despite reports from local observer groups that the election had been marred by widespread irregularities, the OAS observer mission provided the results with its stamp of approval. Opposition parties pledged to boycott the runoff vote, and, under increasing pressure from street protests, the electoral council postponed the election. The OAS eventually acquiesced to Haitian demands for an audit of the vote, and even sent a special mission to negotiate the end of Martelly’s mandate in early 2016 — which paved the way for a transitional government, an audit of the vote, and a do-over election in November 2016. Notably, the rerun election was held under the same electoral law and without reopening candidate registrations.

The negotiated end of Martelly’s mandate actually provides a precedenct in the current crisis, the seven human rights organizations argue. The beginning of Martelly’s mandate was delayed a number of months by the 2010 electoral fracas, nevertheless, Martelly left office on February 7, 2016 — months before he hit five years. (Notably, former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide was not allowed to serve his full first term after returning to the presidency in 1994. This followed the 1991 coup d’etat that saw Aristide deposed and exiled for a total of three years.)

In their letter to Almagro, the seven organizations point out that Martelly himself acknowledged this in his parting speech. “[M]y mandate is nearing its end,” Martelly said at the time. “According to Article 134-1 of the Mother Law, the presidential term is five (5) years. This period begins and ends on February 7 of the fifth year of the mandate, regardless of the start date.”

The key question facing Haiti now is: when did the constitutional mandate of the president actually begin? The Moïse administration has argued the constitution is clear — and confers a president with a five-year mandate. If Moïse took office in February 2017, his term should therefore conclude in February 2022. The rights organizations, however, contend that Moïse should not be able to benefit from the fraud-pocked election which had to be reheld. The constitution, they argue, is clear that the presidential mandate begins following the election — meaning that, constitutionally, the mandate began in February 2016, following the October 2015 vote, and will end in 2021, regardless of when the president himself took office.

The rights organizations also point to the 2015 electoral law, which notes that, if the election is not held in the constitutional timetable, “The term of office of the President of the Republic shall end on the seventh (7th) of February in the fifth year of his term of office, regardless of the date of his entry into office.”

Further, the organizations point to the recent expiration of parliaments’ terms as an additional precedent. On January 13, in a tweet, President Moïse declared the terms of parliament complete. However, as the organizations note, some deputies and senators had not completed their full mandate. “As the legislature ended on the second Monday of January 2020, all Congressman, regardless of the year in which they took office, left Parliament.”

The focus on a constitutional interpretation, however, obscures a deeper issue. No election has been held under the Moïse administration, no elections are scheduled, and there is no functioning parliament to serve as a check on the presidency.

Last week, the Haitian government requested support from the OAS in organizing elections this year, but opposition politicians — emboldened by nearly two years of popular frustration and protests against the Moïse administration and government corruption — have shown little willingness to participate in elections organized by the current government.

For much of the past two years, the donor community, including the OAS, has advocated for dialogue — a political negotiation to reach agreement around elections, mandates, and governance. Regardless of when exactly the president’s term ends, it has become clear that the only way forward will be through a broad, consensual, and Haitian-led political accord. Allowing Moïse to stay in office until 2022 without addressing the other, related, political issues such as elections, will only serve to kick the can down the road. The statement from the OAS Secretary General won’t help in the slightest, and will only further prove to Haiti’s opposition that the OAS is serving as an overt political actor in Haiti as opposed to a neutral arbiter.

The relationship between President Moïse and the OAS and Secretary General Almagro has deepened in recent years. In January 2019, Haiti sided with the United States and voted at the OAS to condemn the Maduro government in Venezuela and recognize the Juan Guaidó “administration.” In doing so, Haiti broke from the majority of CARICOM countries, which have long voted as a bloc — especially in matters of concern to national sovereignty.