November 29, 2024

New York Times columnist Christopher Caldwell devoted his Thanksgiving piece to describing the German sociologist Wolfgang Streeck’s views on capitalism and democracy. I have not read much of Streeck’s work, but as recounted by Caldwell, he gets many of the basic facts about the US economy badly wrong.

According to Caldwell’s account, capitalists were willing to sacrifice profits in the decades after World War II for stability. This meant less dynamism but allowed for broadly shared prosperity and thriving democratic institutions.

“Between the end of World War II and the 1970s, he reminds us, working classes in Western countries won robust incomes and extensive protections. Profit margins suffered, of course, but that was in the nature of what Mr. Streeck calls the ‘postwar settlement.’ What economies lost in dynamism, they gained in social stability.”

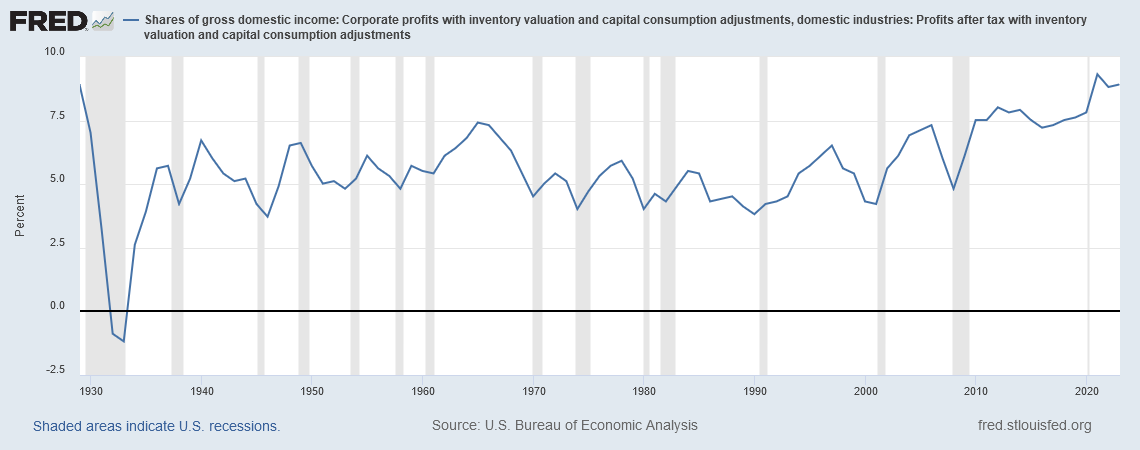

The problem with this account is that, at least in the United States there is no evidence that capitalists were sacrificing profit. Here’s after-tax corporate profits as a share of GDP since World War II.

As can be seen, it has only been in the years since the collapse of the housing bubble (the financial crisis) that profit shares consistently exceeded their average in the quarter century following World War II. (The rise in profit shares in the bubble years was largely illusory, as banks booked large profits on loans that subsequently went bad.)

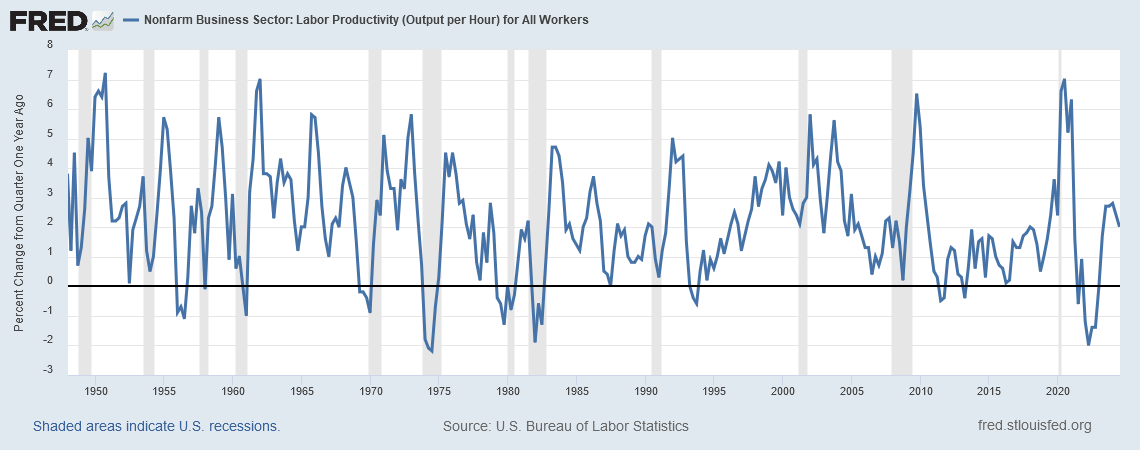

There was also no lack of dynamism in this period when capital was supposedly sacrificing profit. The quarter century from 1947 to 1973 was by far the most rapid period of productivity growth the U.S. has seen.

Where Did the Money Go?

In Caldwell’s telling, the world economy was shaken by the oil price hikes in the 1980s and capital’s response was to change the rules to increase its take. The upward redistribution of income since 1980 has been widely documented, with the wages of ordinary workers no longer keeping pace with productivity growth. However, the gains were not going to corporate profits, or at least not until the years following the Great Recession.

The redistribution was going from ordinary workers, like factory workers, construction workers, and retail clerks, to higher end workers like doctors, lawyers, engineers, as well as Wall Street types and top-level executives. This matters both from a political and economic standpoint.

From a political standpoint, it is entirely reasonable that the ordinary workers who are losers in this story would resent the more highly educated workers who are the beneficiaries. There is even more reason for this resentment when we consider that the upward redistribution was done by deliberate policy, not just the natural working of the market.

The most visible engineering was with trade policy. Our trade deals were crafted to put downward pressure on the pay of manufacturing workers by putting US manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world. The predicted and actual result of this policy was the loss of millions of manufacturing jobs and downward pressure on the wages of the remaining jobs.

This policy was not “free trade.” There was no comparable effort to expose doctors and other highly paid professionals to the same sort of competition. It was a policy of selective protectionism.

We also made patent and copyright protection longer and stronger, shifting more than $1 trillion annually from the rest of society to those in a position to benefit from these government-granted monopolies.

These monopolies are a huge factor in the upward redistribution of income in the last half century. Bill Gates would still be working for a living if the government didn’t threaten to arrest anyone who copied Microsoft’s software without his permission.

The government also chose to foster a bloated financial sector, which is another source of great fortunes in this period. Government support has taken a variety of forms — most visibly deposit insurance and bailouts in situations where the free market would put major financial firms out of business — but there are many other ways in which policy has encouraged the growth of the industry at the expense of economic efficiency.

All this matters because we need to recognize that capitalism is a far more flexible system than Streeck would have it, according to Coldwell’s telling. Capitalism is still capitalism with shorter and weaker copyright and patent protections.

It is also still capitalism with a substantially downsized financial sector. And it is still capitalism with rules of corporate governance that make it more difficult for CEOs to get tens of millions of dollars in pay each year.

It is important for people to have a clear idea of where the money is if we are going to fix the system and maintain a democratic future. The beneficiaries of the rigging will viciously fight any efforts to undo their work, so this is not an easy process. But it is at least a possible one when we know the real story.

Yes, this is the topic of my book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer. (It’s free.)

Comments