January 15, 2015

Last Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its December 2014 jobs report. Most media outlets have focused their reporting on the U-3 unemployment rate, which fell to 5.6 percent last month.

However, the U-3 unemployment rate is an imperfect measure of joblessness. In order to be counted as unemployed, a prospective worker must “have actively looked for work in the prior 4 weeks.” This means that if someone has been searching for work for a long period of time, but has become dissatisfied with their job prospects and hasn’t applied for any jobs over the previous month, he or she is no longer counted as “unemployed.”

Some have tried to correct for this bias by looking at labor force participation rates (LFPR); this is also misleading, mostly because labor force participation doesn’t distinguish between employment and unemployment. (A prospective worker is counted as being part of the labor force if he or she is either employed or unemployed and searching for work. This means that if 50 percent of a country’s citizens were employed and 30 percent were unemployed, its LFPR would be 80 percent; however, the LFPR would also be 80 percent if 75percent were employed and only 5 percent were unemployed. Obviously it’s important to distinguish between these two scenarios.)

In order to correct for these and other problems, it’s best to analyze employment-to-population (EPOP) ratios. (My colleague Janine Duffy used EPOP ratios for women to compare the effects of various family leave policies across OECD countries on women’s employment; see her post here.) However, if you just look at the EPOP ratio for the U.S. as a whole, you miss out on the changing age distribution of the population: if the population is aging, a greater percentage of the population may hit retirement age and willingly retire, which doesn’t imply a weaker job market. Conversely, if the population is becoming younger, a greater percentage of the population may enroll in high school or college; yet this tells us nothing about employment opportunities for working-age Americans.

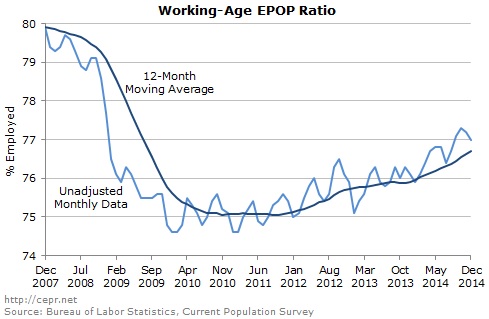

A simple way to correct for a changing age distribution is to limit one’s analysis to the working-age population; the BLS tracks the EPOP ratio for Americans aged 25 to 54, a group that is unlikely to be retired or in school. The most recent job figures show that 77.0 percent of all 25-to-54 year-olds were employed in December.

More importantly, the working-age EPOP ratio shows that the U-3 unemployment rate is significantly overstating the strength of America’s recovery. When the recession began in December 2007, the unemployment rate stood at 5 percent; it famously peaked at 10 percent in October 2009. Since the unemployment rate has now fallen to 5.6 percent, it would be easy to conclude that the labor market has mostly recovered and that the negative hangover effects from the recession will soon be gone.

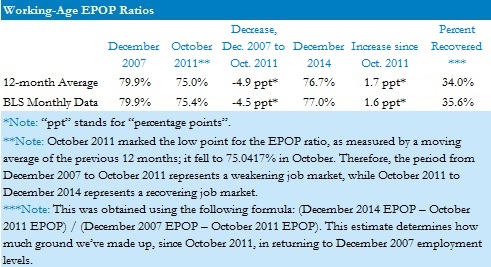

The working-age EPOP ratio tells a far different story. Far from having “mostly recovered,” the job market appears to have made up just over a third of the ground lost during and immediately following the recession:

There are two takeaways from the table. First, despite the slight downturn in December of this year – the working-age EPOP ratio fell 0.2 percentage points – the longer run trend shows that employment has been increasing steadily since October 2011. There is always some variation in the monthly data, and December tends to be a weak month: the working-age EPOP ratio has fallen 0.2 percentage points in each of the previous four Decembers (2011-2014). However, December 2014’s working-age EPOP ratio was 0.9 percentage points higher than December 2013’s ratio, and the general trend in employment is clearly positive:

The second takeaway is that, despite a fine jobs report for December, this is hardly the time to begin cutting the deficit or raising interest rates. As I stated earlier, if you were to limit your analysis to changes in the U-3 unemployment rate, you’d come away with the impression that the job market has almost completely recovered. However, the actual weakness of the job market, as expressed in the working-age EPOP ratio, tells us that stimulus policies such as tax cuts, increases in government spending, lower interest rates, and a weakened dollar would all increase employment. This is hardly the time to begin pulling back on monetary or fiscal stimulus.

On the whole, this was a good jobs report. But we’re a long way from true recovery, so policymakers should still be looking to stimulate the economy and increase employment.