July 09, 2016

George Will used his column to complain that the Federal Reserve Board is redistributing upward with its low interest rate policy. Since this is a source of confusion that extends well beyond Will, it is worth taking a few minutes to address this issue directly.

The essence of the argument is that low interest rates drive up asset prices like stock and assets, thereby increasing the wealth of people who own these assets. Since the rich own most of these assets, especially stock, the argument is that the higher asset prices are helping the rich at the expense of the rest of us.

Before addressing the logic of this point, it is first worth examining the extent to which asset prices have risen as a result of low interest rates. The pre-recession peak of the S&P 500 was 1576 on October 1, 2007. Since then the market has risen by roughly 35 percent to 2130. The economy has grown by just over 25 percent over the same period. Virtually no one thought there was a stock bubble in 2007. (I warned people about the market at the time, not because of a stock bubble, but rather because I expected the crash of the housing bubble to lead to a severe recession, which the market was not anticipating.)

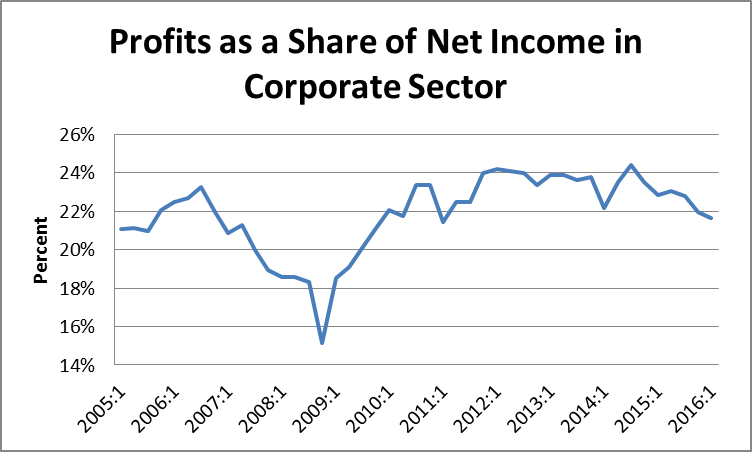

If the market wasn’t in a bubble in 2007, it’s hard to make the case it faces one today. Also, if there has been a permanent shift to higher profits (which I don’t believe, but many economists claim), then the price to trend earnings ratio would be roughly the same today as it was before 2007.

For those keeping score, the federal funds rate was 5.0 percent in October of 2007 and the 10-year Treasury rate was 4.5 percent. That compares to today’s rates of around 0.3 percent for federal funds and 1.6 percent for 10-year Treasury bonds. If the argument is that low interest rates have given us a stock bubble, the Fed has not bought itself much for its efforts.

On the housing front, the most recent Case-Shiller index puts real house prices about 20 percent below their bubble peaks and about 40 percent above their mid-1990s levels. This valuation is likely affected by interest rates. Historically, house prices have not been hugely affected by interest rates, but we are seeing extraordinarily low mortgage rates.

A prime 30-year mortgage can be gotten at around 3.5 percent. If we assume 2.0 percent future inflation, that translates into a 1.5 percent real rate. By contrast, the mid-1990s rate would have been close to 8.0 percent. With a 2.5 percent inflation rate, that translates into a 5.5 percent real mortgage interest rate. So this sharp decline in interest rates probably explains much of the increase in house prices relative to pre-bubble levels. Of course, in a weak economy, we would expect lower interest rates in any case, so the Fed can’t get all the blame/credit on this one.

Okay, so we may have a very modest interest story for stock prices, and a bit more compelling case on house prices, how does this affect inequality? Well, these are telling us about asset prices, not income, so immediately at first glance it tells us zero. People who have a more valuable asset can only benefit in terms of current consumption if they borrow against or sell it, but by itself the higher asset value doesn’t do anything for them.

To take the simplest case, suppose a homeowner sees the inflation-adjusted price of her house rise from $200,000 to $280,000. As long as she lives in her home, this doesn’t let her buy anything she could not previously, unless she chooses to borrow against her house. Of course, people do borrow against their homes, so there is something to this story. There is also the fact that it will be harder for non-homeowners to become homeowners if they need a larger down payment. On the other hand, the extraordinarily low mortgage interest rates will make the monthly payment for the same house considerably less. (Do the arithmetic if you don’t believe me.)

In short, there is certainly a modest upward redistribution from non-homeowners to homeowners associated with the interest rate induced run-up in house prices. This is not particularly a one percent story, since almost two-thirds of households are homeowners, but it is nonetheless a redistribution of claims to resources from those who have less to those who have more.

In the case of stocks, the ownership is much more concentrated among the one percent, but there is not much of a case for an interest rate induced increase in prices. Stock prices, adjusted for the size of the economy, are somewhat higher than their pre-recession level, but there just is not much of a story here.

But let’s get back to the impact of interest rates on the economy. Lower interest rates affect the economy through several channels. Probably the most important one in this downturn is the reduction in mortgage interest burdens as millions of new homeowners were able to get low interest rate mortgages and tens of millions of existing homeowners refinanced at lower interest rates.

This is real money. A 2.0 percentage point interest rate reduction on a $200,000 mortgage translates into $4,000 a year in interest rate savings. This is equivalent to almost an 8.0 percent increase in income for the median family. This gives a direct boost to the economy since the borrowers are likely to spend a larger share of their income than the folks getting the interest.

This brings up an important distributional point. While the owners of assets have higher valued assets, they are also getting less income per dollar on these assets. If Peter Peterson bought $100 million worth of Treasury bonds today, he would get just $1.6 million in annual interest payments. If bought $100 million in Treasury bonds a decade ago he would have gotten more than $5 million a year in annual interest payments. For this reason, the drop in interest rates is an important story of downward redistribution, since borrowers on average are less wealthy than lenders.

In addition to the impact of lower mortgage interest rates on consumption, they also encourage home buying and homebuilding. The latter is sort of an inescapable part of the higher house price story.

In addition to the benefits from lower mortgage interest rates, lower interest rates also make it easier for businesses to borrow to finance investment. While most research shows this effect is limited, it is not zero. Investment is at least somewhat higher today than it would be if the Fed had not pursued its low interest rate policy.

There is a similar story with state and local governments that borrow to finance infrastructure. Low interest rates have made it easier for them to make infrastructure investment. Also, since they pay less money in interest, they have more money available to pay for other goods and services. This applies to the federal government as well. Even though its borrowing is not limited in the same way as it is for state and local government, the deficit cultists have probably allowed more non-interest spending than if we were paying another $100 billion or so each year in interest.

And, lower interest rates will reduce the value of the dollar, other things equal. This means that U.S. goods and services will be more competitive in the world economy, increasing our net exports.

The sum total of these effects has likely been to reduce the unemployment rate by 1.0–2.0 percentage points compared to a situation in which the Fed was not doing anything to try to boost the economy. The effect of lower unemployment is higher redistributive to those at the middle and bottom end of the income ladder. It leads to both a shift from capital to labor and also a shift to less-educated workers since their unemployment rates fluctuate most during the business cycle.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

In fact, the drop in unemployment in the last three years has eliminated most of the redistribution from wages to profits that we saw in the downturn. The shift of income to labor in this period of roughly 2.5 percentage points, from over 24.0 percent to under 22.0 percent, is equivalent to a 3.0 percent pay hike for the average worker. This is in addition to hugely increasing the probability they would have a job. The simple rule of thumb is that the unemployment rate for African American workers averages twice the unemployment rate for white workers and the unemployment rate for African American teens averages six times the unemployment rate for white workers. So if the Fed’s actions have lowered the overall unemployment rate by 1.0–2.0 percentage points, they have hugely benefited African Americans and other disadvantaged groups.

Long and short, when we hear George Will being concerned about giving the rich money, it’s worth asking questions. In this case, we find that the policy in question is giving more people jobs, making it harder for people like Will to find good help and giving workers more bargaining power so that they can get higher wages. It is not in any meaningful way redistributing income upward.

Comments