October 20, 2014

Gretchen Morgenson had a great column in Sunday’s New York Times that pulls back the veil of secrecy surrounding pension fund investments in private equity. PE firm Carlyle recently agreed to pay $115 million to settle charges that it had engaged in illegal activities. Shockingly, neither Carlyle nor the firm’s executives and shareholders will pay a penny of this amount. Instead, it’s the pension funds and other limited partners in this PE fund that are on the hook for paying the fine. As Morgenson points out:

Instead, investors in Carlyle Partners IV, a $7.8 billion buyout fund started in 2004, will bear the settlement costs that are not covered by insurance. Those investors include retired state and city employees in California, Illinois, Louisiana, Ohio, Texas and 10 other states. Five New York City and state pensions are among them.

The retirees — and people who are currently working but have accrued benefits in those pension funds — probably don’t know that they are responsible for these costs. It would be very hard for them to find out: Their legal obligations are detailed in private equity documents that are confidential and off limits to pensioners and others interested in seeing them.

Indeed, Morgenson only knows about this because in a rare coup, the New York Times was able to obtain a copy of an agreement that limited partners in a Carlyle fund signed. In general, the secrecy surrounding the agreements that pension funds and other limited partners sign has made it impossible to tally up the total fees and expenses PE firms charge pension funds and their other PE fund partners. Despite the fact that public employee pension funds provide almost a quarter of the capital committed to private equity, while private pension funds commit another 10 percent, the terms of these partnership agreements are kept secret from the workers and retirees whose money is at stake. This is especially egregious in light of the sunshine laws that in most states require transparency and accountability on the part of government agencies, including public pension funds. Yet, as Morgenson documents, the version of the Limited Partner Agreement with Carlyle that the New York Times obtained through a Freedom of Information request was heavily redacted – 108 of its 141 pages were either entirely or mostly blacked out.

In an otherwise excellent article that should be read by every worker and retiree whose retirement savings are in a pension fund, Morgenson makes two misstatements that need to be corrected. First, she uncritically repeats the PE industry’s false characterization of its own activities.

“Private equity firms now manage $3.5 trillion in assets. The firms overseeing these funds borrow money or raise it from investors to buy troubled or inefficient companies. Then they try to turn the companies around and sell at a profit.”

In fact the best econometric evidence (see here www.nber.org/papers/w17399 and here www.nber.org/papers/w19458) finds that private equity funds overwhelmingly buy healthy companies that they think they can sell at a profit in three to five years. In an analysis that predates the recent recession and financial crisis, the researchers found that establishments acquired by private equity funds have higher rates of employment growth and pay higher wages at the time they are acquired than do comparable companies not bought by PE funds. Within a few short years, however, these establishments have slower employment growth (or faster job destruction) and pay lower wages than the establishments in the control group.

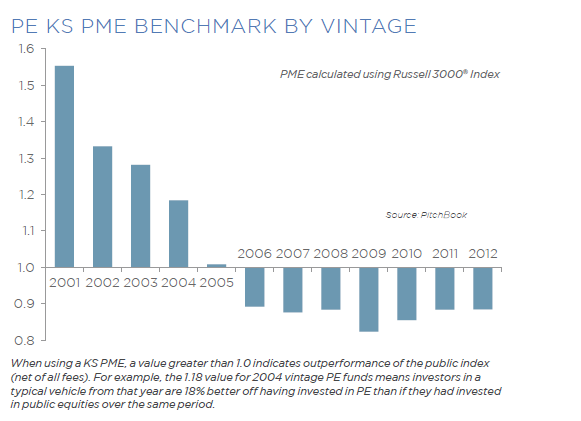

Second, the rates of return that Morgenson quotes for PE funds are seriously misleading. Two things need to be taken into consideration in order to accurately evaluate how PE funds have performed compared to the stock market. First, we need to take into account when the PE fund was launched – its ‘vintage.’ PE funds of each vintage need to be compared separately to the stock market in order to see how the funds have performed over their lifetime to date. Second, the appropriate measure to use – and the one used by noted finance economists such as the University of Chicago’s Steven Kaplan – in evaluating private equity performance is a measure called the Public Market Equivalent. The chart below, from PitchBook – a widely used source of data on private equity, uses the Public Market Equivalent benchmark developed by Steven Kaplan and Antoinette Schoar.

As the chart shows, the median PE fund in each vintage since 2005 has failed to beat the stock market. Even this is not entirely accurate since it doesn’t take into account the much larger capital commitments by private equity partners during boom periods than during recessions. But the message is clear. Pension funds and other limited partners would have been better off investing in a passive stock market index fund.

Comments