January 17, 2012

Hungary is being led by a right-wing populist government that seems to have a questionable commitment to democracy. The steps it has taken to end the independence of the judiciary and undermine the fairness of future of elections are ominous. However, the NYT’s efforts to construct an economic case against the government fall badly short of the mark.

The NYT tells us that:

“Hungary serves as a cautionary tale for those who argue that Greece could regain competitiveness by reintroducing its currency. The drachma would plunge against the euro, the theory goes, and allow Greek products to compete on price with countries like Turkey.

‘Whatever you win today, it shoots you back tomorrow,’ said Radovan Jelasity, chief of the Hungarian unit of Erste Bank, an Austrian institution.

….

In theory, the plunge of the currency should help the economy by making Hungarian products less expensive abroad and cutting the cost of labor relative to neighboring countries.

But economists and business people say the advantages of a weak currency are more than canceled out by negative factors, like soaring prices for imported fuel or imported components for Hungarian factories, not to mention higher payments on foreign currency loans.

….

But the economic climate is grim, with 10.7 percent unemployment and inflation of 4.3 percent even as the economy heads into recession.”

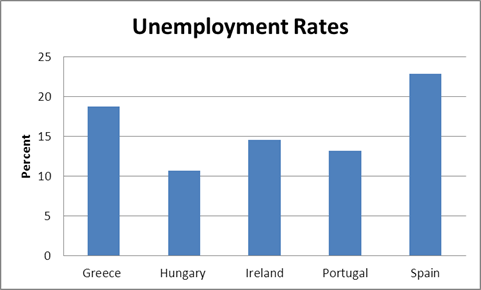

Okay, so the word is that things are really bad in Hungary with its 10.7 percent unemployment rate. Let’s see how that looks compared to the competition.

Source: OECD.

If we compare Hungary to the debt crisis countries that remain within the euro it is looking pretty good. The closest among this group is Portugal, with an unemployment rate of 13.2 percent. The others are considerably worse. (The unemployment rates given are all the most recent available, which differs somewhat across countries.)

The 4.3 percent inflation rate might be somewhat higher than is desired, but hardly a crisis. The United States had higher inflation rates many times in the last 50 years without serious economic disruptions. Furthermore, in the context of a heavily indebted population, inflation performs the valuable function of reducing the real value of debt. It is also a necessary part of the adjustment process for a country looking to regain competitiveness by reducing the value of its currency.

The moral of this story is that Hungary’s government may actually be led by bad guys, but it doesn’t seem that their policies have had terribly negative economic consequences thus far. That could change down the road, but it still appears that Hungary’s economy is doing relatively well.

Comments