October 13, 2014

Unfortunately that is not an exaggeration. He concludes his column this morning about the difficulties the folks at the I.M.F. meetings have in promoting growth by telling readers:

“We’re witnessing a historic break from the past. I think the IMF forecasters deserve some sympathy. They’re dealing with a global economy that strains our intellectual understanding and is outside their personal experience. We don’t know what we don’t know.”

Samuelson tells us that there are three huge problems. The first one is:

“Sobered and scared, people and businesses delay consumption and investment. To prepare for the next crisis, they reduce debts (“deleverage”) and increase savings. Firms hoard profits.”

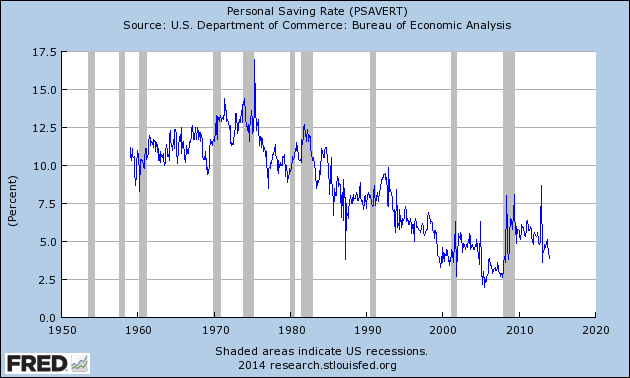

The problem is that this is not really true, especially in the United States. Consumption is actually quite high relative to disposable income (which means savings is low), albeit not quite as high as at the peaks of the stock and housing bubbles when people had trillions of dollars of ephemeral wealth.

The investment share of GDP is not quite back to its pre-recession peak, but it’s above its 2005 share. No one in 2005 was saying that firms were scared and deleveraging.

Another problem Samuelson lists:

“The third problem is the cost of maturing welfare states. The United States, Europe and Japan (about two-fifths of the global economy) face comparable problems. Their populations are aging. Their governments are committed to paying costly retiree benefits, and these same governments are already running sizable budget deficits. Curbing deficits — necessary for some countries to maintain financial confidence — means cutting spending or raising taxes.”

There are a couple of big problems with this one. First, those of us who can remember all the way back to 2007 will recall that budget deficits were not especially large in that year. The United States had a deficit of 1.6 percent of GDP, a level that can be sustained forever since the debt to GDP ratio was falling. Spain, Ireland, and most of the rest of Europe had budget surpluses.

There has been some aging of populations in the last seven years, but the overwhelming part of the shift from surplus to deficit has been due to the loss of demand in the economy. This has led to higher unemployment, which in turn means less tax revenue and more transfers like unemployment insurance.

So we clearly have a problem of a lack of demand, which leads to larger budget deficits, but Samuelson gives us no reason to believe that somehow we can’t afford the welfare state. (We get it, he doesn’t like the welfare state.) Remember to keep your eye on the ball. His unaffordable welfare state story is fundamentally a story on inadequate supply. Not enough goods and services to meet the demand. We would expect that to lead to issues like high interest rates and inflationary pressures. Anyone see anything that looks like that around here?

Finally, we get to the third problem (#2 on Samuelson’s list):

“Another problem is the legacy of global trade imbalances in the 1990s and early 2000s, when China and some other countries ran huge surpluses and the United States and some others ran huge deficits. This boosted growth for the exporters and their raw material and component suppliers — Australia, Brazil, South Korea and others. But this system depended on the voracious spending of Americans and Europeans. When the spending declined, the export bubble burst.”

Bingo!

Samuelson hits the jackpot on this one. The problem is that developing countries, who according to the old-fashioned economics textbooks are supposed to be importers of capital, are instead exporters of capital. In other words they have been running massive trade surpluses with rich countries. The textbook story is that the rich countries lend the poor countries the capital they need to develop, which means the rich countries run trade surpluses.

The trade deficits that the United States and other rich countries have experienced create a huge gap in demand. This gap was filled in the 1990s by the stock bubble and in the last decade by the housing bubble. However with no bubble to fill this gap in demand growth lags and unemployment remains high.

This makes the problem all very simple. We need demand in the economy. The obvious and most immediate route is to boost government spending to deal with little things like global warming, or education, or health care. But that is ruled out by deficit superstitions.

We can also take the perfectly good route of reducing supply through work sharing and policies that promote leisure like paid parental leave and sick days. We could even have longer vacations.

Also, we could try to reverse the trade deficits. It’s not a mystery where these came from. Capital was following the textbook story, flowing from rich countries to poor countries, until the East Asian financial crisis. (The United States had modest trade deficits, but Europe and Japan had large surpluses.) This changed when the dollar soared following the crisis.

This was a direct result of the botched bailout engineered by the Clinton administration and the I.M.F. They insisted that the countries of the region repay their debts in full, which meant that they had to export like crazy to pay the bills. Not only did the East Asian countries follow this route, but the whole developing world adopted the same path, hoping to never have to deal with the I.M.F. on the same terms as the East Asian countries.

Correcting this wrong track is the main problem facing the world economy today. In other words, get the dollar down. That would boost our exports. (The euro should also fall against developing world currencies.) If we had a trade deficit of 1.0 percent of GDP (@$175 billion a year), instead of the current 3.0 percent of GDP, it would translate into roughly 4.2 million additional jobs. That would make the economy look an awful lot better and it’s all very simple.

Comments