November 03, 2015

The RushCard is a prepaid debit card marketed to unbanked and underbanked populations — people not usually served by traditional banks and card issuers because they are categorized as high-risk and tend to be poorer. Started in 2003 by Russell Simmons, originally a hip-hop executive, the RushCard has faced criticism since its beginning mainly for charging excessively high fees. Criticism has mounted in recent weeks, as RushCard users reported that they were locked out of their accounts and could not use their cards for transactions, although the cards still allowed users to add money to them. This meant that people, some of whom had their paychecks directly deposited to their RushCards, were unable to access any money on their cards. People living paycheck-to-paycheck were unable to pay for rent or child care, buy food, or pick up medicine.

There’s no doubt that the RushCard and other cards like it serve a purpose. It is available to anyone, and is especially attractive to those wary of the traditional banking system. The banking industry has certainly provided grounds for wariness, with its history of redlining, the proliferation of predatory loans leading up to the financial crisis, and discriminatory or predatory practices. To them, “Uncle Rush”, as Simmons calls himself, seems different. The RushCard is also less expensive and more convenient than alternative financial services marketed to the unbanked or underbanked, like check cashing and payday loans, and it has the caché of a regular debit card. The fees the card charges can also be rationalized: it’s better to know about them upfront and how much using the RushCard will cost, than to deal with a bank that might be less forthcoming about what its services cost.

Even though the RushCard is useful to some people, it’s not the best solution for the unbanked and underbanked. Recent events have underscored that reality. Simmons and RushCard said the disruption was due to a “technology transition” and tried to placate angry customers on social media, including offering to waive fees for a period of time. The disruption lasted for almost two weeks, although there was little media coverage of the situation. (One commenter contrasted the disruption to the launch of Healthcare.gov, which was front page news but didn’t actually adversely impact anyone’s health insurance coverage.)

In addition to this one-time fiasco, the basic terms of the card are not especially favorable. RushCard charges fees for simply having an account or making a transaction. These fees can add up quickly, squeezing already vulnerable customers. (Other prepaid cards have even more egregious fees.)

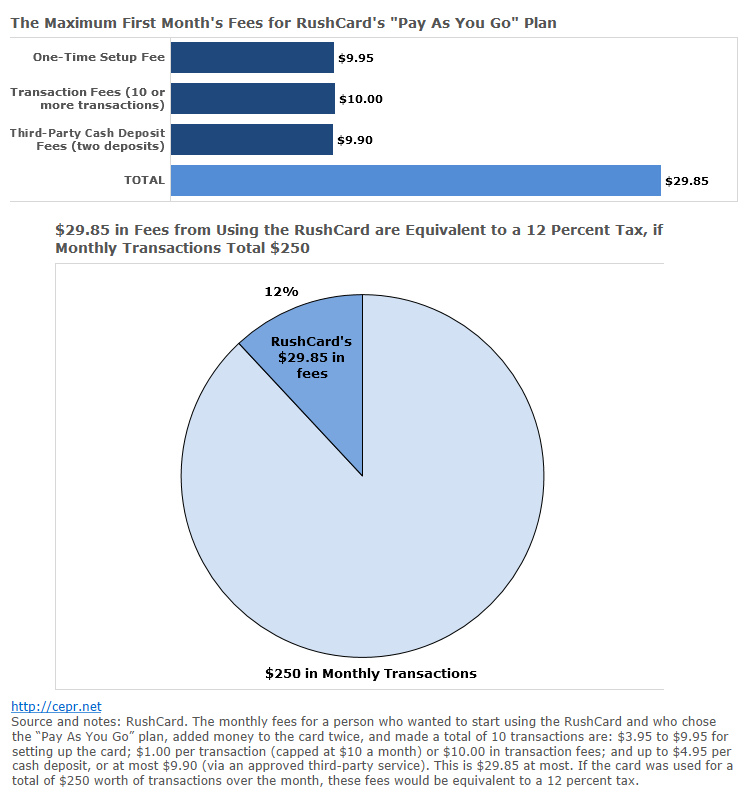

For example, the monthly fees for a person who wanted to start using the RushCard and who chose the “Pay As You Go” plan, added money to the card twice, and made a total of 10 transactions are:

-

$3.95 to $9.95 for setting up the card;

-

$1.00 per transaction (capped at $10 a month) or $10.00 in transaction fees; and

-

Up to $4.95 per cash deposit, or at most $9.90 (via an approved third-party service).

This is $29.85 at most. If the card was used for a total of $250 worth of transactions over the month, these fees would be equivalent to a 12 percent tax.

To be fair, banks and credit unions sometimes charge monthly maintenance fees, but they rarely charge transaction or deposit fees. For comparison, Chase Bank, the largest bank by assets in the U.S., charges a $12.00 monthly maintenance fee for their basic checking account. Given that there are many financial institutions to choose from, even these monthly maintenance fees are easy to avoid, especially at online-only banks.

The RushCard fiasco has already led to a lawsuit and an investigation from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. These are inevitable consequences. But consumer protections should already be in place to deal with these situations, stepping in much sooner to make sure that RushCard customers have access to their money or emergency financing. In financial decisions, regulations should guide consumers to good decisions as, for example, the Department of Labor’s proposed rules requiring investment advisers have a fiduciary duty to their clients would do.

Importantly, there are also solutions that go beyond consumer protections. Public banking can work alongside the traditional banking system, similar to how Social Security exists alongside private retirement options. The most notable proposal for public banking starts with the Post Office, which released a report discussing how it could expand financial services for the underserved. The Post Office could go further and become a full-fledged bank too (as it once was), which would be an attractive alternative to products like the RushCard. The Post Office is trusted and reliable, and it has physical infrastructure across the country that would make it convenient for customers to visit. In fact, 59 percent of post offices are in bank deserts — areas with one or zero bank branches.

The banking operation could provide basic financial products: savings and checking accounts, and certificates of deposit, for example, which have low fees and pay a reasonable rate of interest. The Post Office could even be a partner with state agencies that administer various cash transfer or assistance programs like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), food stamps (SNAP), or Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and provide those benefits via a Post Office debit card. This would simplify these programs, and make managing money and benefits easier for recipients. Those who are incarcerated could also use the Post Office’s services. Senator Cory Booker recently opened an investigation into the fee-riddled “release cards” some ex-offenders receive when leaving prison, requesting that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau regulate these cards and the companies that provide them, like JPay. As an alternative, ex-offenders’ accounts during the time they are incarcerated could be operated by the Post Office, and when leaving prison, they could be issued a Post Office debit card.

If the Post Office adds these services, they may improve its financial situation. Yet it will also change the way the Post Office is seen by Americans. Instead of being seen as just a business, it could be seen as an important institution that provides much-needed services to everyone, especially the underbanked, unbanked, and formerly incarcerated.

With added consumer regulations and trusted and reliable public options like postal banking available, currently underserved populations can have viable options to bank with.